On D+4 after the Normandy invasion of WW2, the 2nd Panzer Division of the Waffen SS was passing through the Limousin region, in west-central France. “Das Reich” had been ordered to help stop the Allied advance, when SS-Sturmbannführer Adolf Diekmann received word that SS officer Helmut Kämpfe was being held by French Resistance forces in the village of Oradour-sur-Vayres.

Diekmann’s battalion sealed off the nearby village of Oradour-sur-Glane, seemingly unaware of their own confusion between the two villages.

Everyone in the town was ordered to assemble in the village square, for examination of identity papers. The entire population of the village was there, plus another half-dozen unfortunates, caught riding their bicycles at the wrong place, and the wrong time.

The women and children of Oradour-sur-Glane were locked in a village church while German soldiers looted the town. The men were taken to a half-dozen barns and sheds, where the machine guns were already set up.

The women and children of Oradour-sur-Glane were locked in a village church while German soldiers looted the town. The men were taken to a half-dozen barns and sheds, where the machine guns were already set up.

The Germans aimed for the legs when they opened fire, intending to inflict as much pain as possible. Five escaped in the confusion before the SS lit the barn on fire. 190 men were burned alive.

Nazi soldiers then lit an incendiary device in the church, and gunned down 247 women and 205 children as they tried to escape.

Nazi soldiers then lit an incendiary device in the church, and gunned down 247 women and 205 children as they tried to escape.

47-year-old Marguerite Rouffanche escaped out a back window, followed by a young woman and child. All three were shot. Rouffanche alone escaped alive, crawling to some pea bushes where she hid until next morning.

642 inhabitants of Oradour-sur-Glane, aged one week to 90 years, were shot to death, burned alive or some combination of the two, in a few hours. The village was then razed to the ground.

Raymond J. Murphy, a 20-year-old American B-17 navigator shot down over France and hidden by the French Resistance, reported seeing a baby who’d been crucified.

After the war, a new village was built on a nearby site. French President Charles de Gaulle ordered that the “old” village remain as it is; a monument for all time to criminally insane governing ideologies, and the malignity of collective punishment.

Generals Erwin Rommel and Walter Gleiniger, German commander in Limoges, protested the senseless act of brutality. Even the SS Regimental commander agreed and began an investigation, but that came to naught. Within days, Diekmann and most of the men who had carried out the massacre, had been killed in combat.

The ghost village at the old Oradour-sur-Glane stands mute witness to this day, to the savagery committed by black-clad Schutzstaffel units in countless places like the French towns of Tulle, Ascq, Maillé, Robert-Espagne, and Clermont-en-Argonne; the Polish villages of Michniów, Wanaty and Krasowo-Częstki and the city of Warsaw; the Soviet village of Kortelisy; the Lithuanian village of Pirčiupiai; the Czechoslovakian villages of Ležáky and Lidice; the Greek towns of Kalavryta and Distomo; the Dutch town of Putten; the Yugoslavian towns of Kragujevac and Kraljevo and the village of Dražgoše, in what is now Slovenia; the Norwegian village of Telavåg; the Italian villages of Sant’Anna di Stazzema and Marzabotto.

And on. And on. And on.

French President Jacques Chirac dedicated a memorial museum in 1999, the “Centre de la mémoire d’Oradour“. The village stands today as those Nazi soldiers left it, seventy-four years ago today. It may be the most forlorn place on earth.

French President Jacques Chirac dedicated a memorial museum in 1999, the “Centre de la mémoire d’Oradour“. The village stands today as those Nazi soldiers left it, seventy-four years ago today. It may be the most forlorn place on earth.

The story was featured on the 1974 British television series “The World at War”, narrated by Sir Laurence Olivier, who intones these words for the first and final episodes of the program: “Down this road, on  a summer day in 1944. . . The soldiers came. Nobody lives here now. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years. . . was dead. This is Oradour-sur-Glane, in France. The day the soldiers came, the people were gathered together. The men were taken to garages and barns, the women and children were led down this road . . . and they were driven. . . into this church. Here, they heard the firing as their men were shot. Then. . . they were killed too. A few weeks later, many of those who had done the killing were themselves dead, in battle. They never rebuilt Oradour. Its ruins are a memorial. Its martyrdom stands for thousands upon thousands of other martyrdoms in Poland, in Russia, in Burma, in China, in a World at War”.

a summer day in 1944. . . The soldiers came. Nobody lives here now. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years. . . was dead. This is Oradour-sur-Glane, in France. The day the soldiers came, the people were gathered together. The men were taken to garages and barns, the women and children were led down this road . . . and they were driven. . . into this church. Here, they heard the firing as their men were shot. Then. . . they were killed too. A few weeks later, many of those who had done the killing were themselves dead, in battle. They never rebuilt Oradour. Its ruins are a memorial. Its martyrdom stands for thousands upon thousands of other martyrdoms in Poland, in Russia, in Burma, in China, in a World at War”.

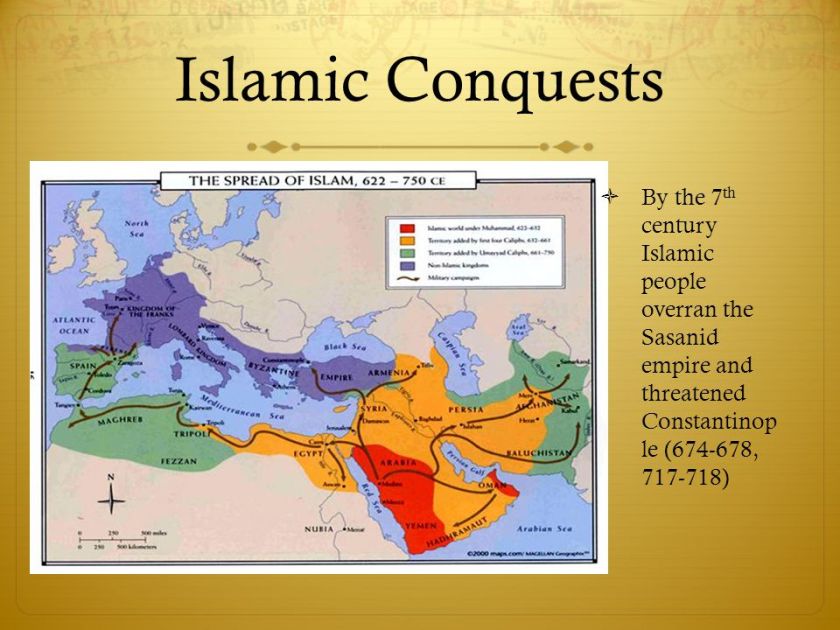

One of those to escape with his life, was a young Abd Ar-Rahman al Ghafiqi. Eleven years later in 732, the now – governor of Al-Andalus would once again cross the Pyrenees, this time at the head of a massive army of his own. Al Ghafiqi’s legions laid waste to Navarre and Gascony, first destroying Auch, and then Bordeaux. Duke Odo “The Great” would be destroyed at the River Garonne and the table set for the all-important decision of Tours.

One of those to escape with his life, was a young Abd Ar-Rahman al Ghafiqi. Eleven years later in 732, the now – governor of Al-Andalus would once again cross the Pyrenees, this time at the head of a massive army of his own. Al Ghafiqi’s legions laid waste to Navarre and Gascony, first destroying Auch, and then Bordeaux. Duke Odo “The Great” would be destroyed at the River Garonne and the table set for the all-important decision of Tours.

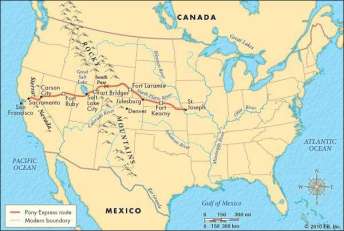

across the Isthmus of Panama or the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in Mexico. The simmering tensions which would lead the nation to Civil War would prove such a system inadequate, as the rapid transfer of information became ever more important.

across the Isthmus of Panama or the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in Mexico. The simmering tensions which would lead the nation to Civil War would prove such a system inadequate, as the rapid transfer of information became ever more important. The Pony Express compressed the standard 24-day schedule for overland delivery to ten days, but the system was a financial disaster. Little more than an expensive stopgap before the first transcontinental telegraph system.

The Pony Express compressed the standard 24-day schedule for overland delivery to ten days, but the system was a financial disaster. Little more than an expensive stopgap before the first transcontinental telegraph system. The first mail carried through the air arrived by hot air balloon on January 7, 1785, a letter written by Loyalist William Franklin to his son William Temple Franklin, at that time serving a diplomatic role in Paris with his grandfather, the United States’ one-time and first postmaster, Benjamin Franklin.

The first mail carried through the air arrived by hot air balloon on January 7, 1785, a letter written by Loyalist William Franklin to his son William Temple Franklin, at that time serving a diplomatic role in Paris with his grandfather, the United States’ one-time and first postmaster, Benjamin Franklin.

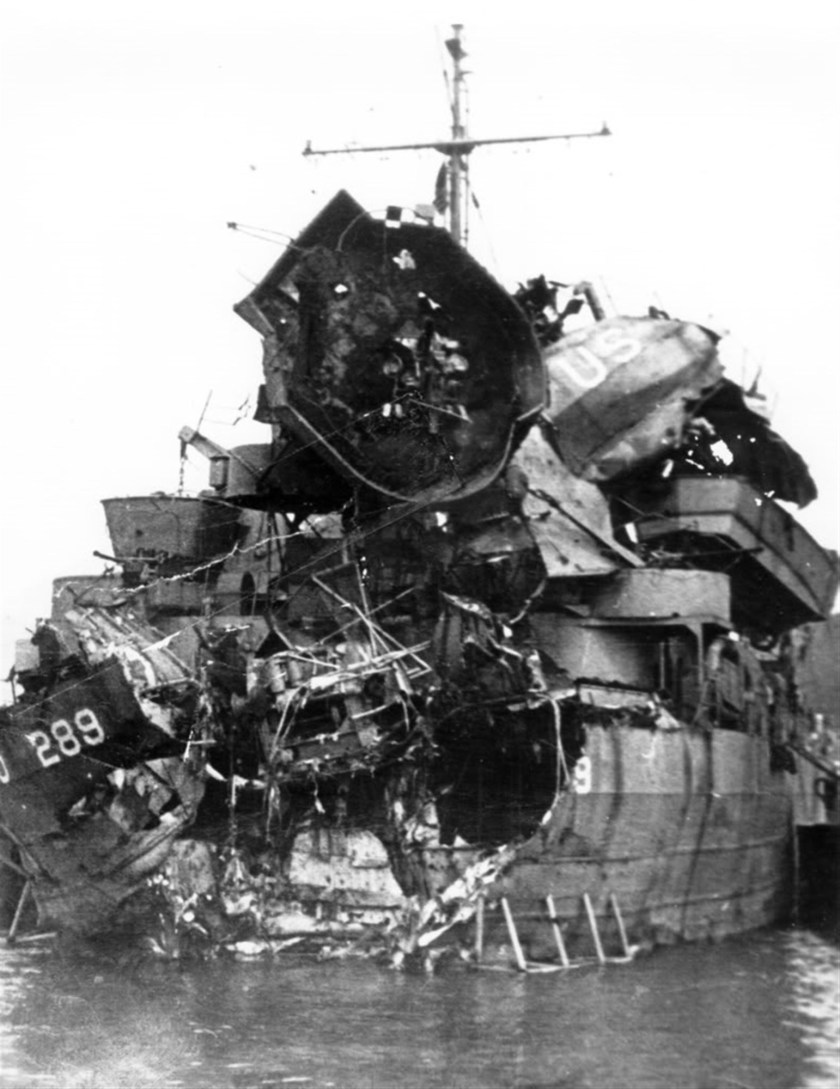

The Regulus was superseded by the Polaris missile in 1964, the year in which Barbero ended her nuclear strategic deterrent patrols. She was struck from the Naval Registry that July, and suffered the humiliating fate of the target ship, sunk off the coast of Pearl Harbor on October 7 by the nuclear submarine USS Swordfish.

The Regulus was superseded by the Polaris missile in 1964, the year in which Barbero ended her nuclear strategic deterrent patrols. She was struck from the Naval Registry that July, and suffered the humiliating fate of the target ship, sunk off the coast of Pearl Harbor on October 7 by the nuclear submarine USS Swordfish.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC. Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

In the late 19th century, Europe was embarked on yet another of its depressingly regular paroxysms of anti-Semitism, when a French Captain of Jewish Alsatian extraction by the name of Alfred Dreyfus was arrested, for selling state secrets to Imperial Germany.

In the late 19th century, Europe was embarked on yet another of its depressingly regular paroxysms of anti-Semitism, when a French Captain of Jewish Alsatian extraction by the name of Alfred Dreyfus was arrested, for selling state secrets to Imperial Germany. Chief Inspector Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Armand Auguste Ferdinand Mercier du Paty de Clam, himself no handwriting expert, agreed with Bertillon. With no file to go on and despite the feebleness of the evidence, de Clam summoned Dreyfus for interrogation on October 13, 1894.

Chief Inspector Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Armand Auguste Ferdinand Mercier du Paty de Clam, himself no handwriting expert, agreed with Bertillon. With no file to go on and despite the feebleness of the evidence, de Clam summoned Dreyfus for interrogation on October 13, 1894.

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus. The public outcry became furious in January 1898 when author Émile Zola published a bitter denunciation in an open letter to the Paris press, entitled “J’accuse” (I Blame).

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus. The public outcry became furious in January 1898 when author Émile Zola published a bitter denunciation in an open letter to the Paris press, entitled “J’accuse” (I Blame).

Perhaps the man was ill at the time but, be that as it may, the die was cast. The conspirators now needed only the right set of circumstances, to put their plans in motion.

Perhaps the man was ill at the time but, be that as it may, the die was cast. The conspirators now needed only the right set of circumstances, to put their plans in motion.

Lay became a lumberjack, a jewelry salesman, and a peanut salesman, before going to work for the Atlanta based Barrett Potato Chip Company. He traveled the Southeast during the Great Depression in his Model A Ford, selling chips to grocery stores, gas stations and soda shops. When the company’s owner died, Lay raised $60,000 and bought the company’s plants in Atlanta and Memphis.

Lay became a lumberjack, a jewelry salesman, and a peanut salesman, before going to work for the Atlanta based Barrett Potato Chip Company. He traveled the Southeast during the Great Depression in his Model A Ford, selling chips to grocery stores, gas stations and soda shops. When the company’s owner died, Lay raised $60,000 and bought the company’s plants in Atlanta and Memphis. Lay began buying up small regional competitors at the same time that another company specializing in corn chips, was doing the same. “Frito”, the Spanish word for “fried”, merged with Lay in 1961 to become – you got it – Frito-Lay. By 1965, Lay’s was the #1 potato chip brand sold in every state.

Lay began buying up small regional competitors at the same time that another company specializing in corn chips, was doing the same. “Frito”, the Spanish word for “fried”, merged with Lay in 1961 to become – you got it – Frito-Lay. By 1965, Lay’s was the #1 potato chip brand sold in every state. The biggest threat that Frito-Lay would ever experience came from the Beer giant Anheuser-Busch, when the company introduced their “Eagle” line of salty snacks in the 1970s. It made perfect sense at the time, a marketing and distribution giant expanding into such a complementary product category, what could go wrong? Frito-Lay profits dropped by 16% by 1991 and PepsiCo laid off 1,800 employees, but Eagle Snacks never turned a profit in 16 years. Anheuser-Busch put the company up for sale in 1995.

The biggest threat that Frito-Lay would ever experience came from the Beer giant Anheuser-Busch, when the company introduced their “Eagle” line of salty snacks in the 1970s. It made perfect sense at the time, a marketing and distribution giant expanding into such a complementary product category, what could go wrong? Frito-Lay profits dropped by 16% by 1991 and PepsiCo laid off 1,800 employees, but Eagle Snacks never turned a profit in 16 years. Anheuser-Busch put the company up for sale in 1995. Tom Peters wrote about Frito-Lay in his 1982 book “In Search of Excellence”. The company will spend $150 to make a $30 delivery if that’s what they need to do. Their customer is counting on them. While a transaction like that doesn’t make economic sense, the company prides itself on a 99½% on-time delivery record. Frito-Lay has the highest profit margins in the industry and a 60% market share in an “undifferentiated commodity”, in which their closest competitor has 7%.

Tom Peters wrote about Frito-Lay in his 1982 book “In Search of Excellence”. The company will spend $150 to make a $30 delivery if that’s what they need to do. Their customer is counting on them. While a transaction like that doesn’t make economic sense, the company prides itself on a 99½% on-time delivery record. Frito-Lay has the highest profit margins in the industry and a 60% market share in an “undifferentiated commodity”, in which their closest competitor has 7%.

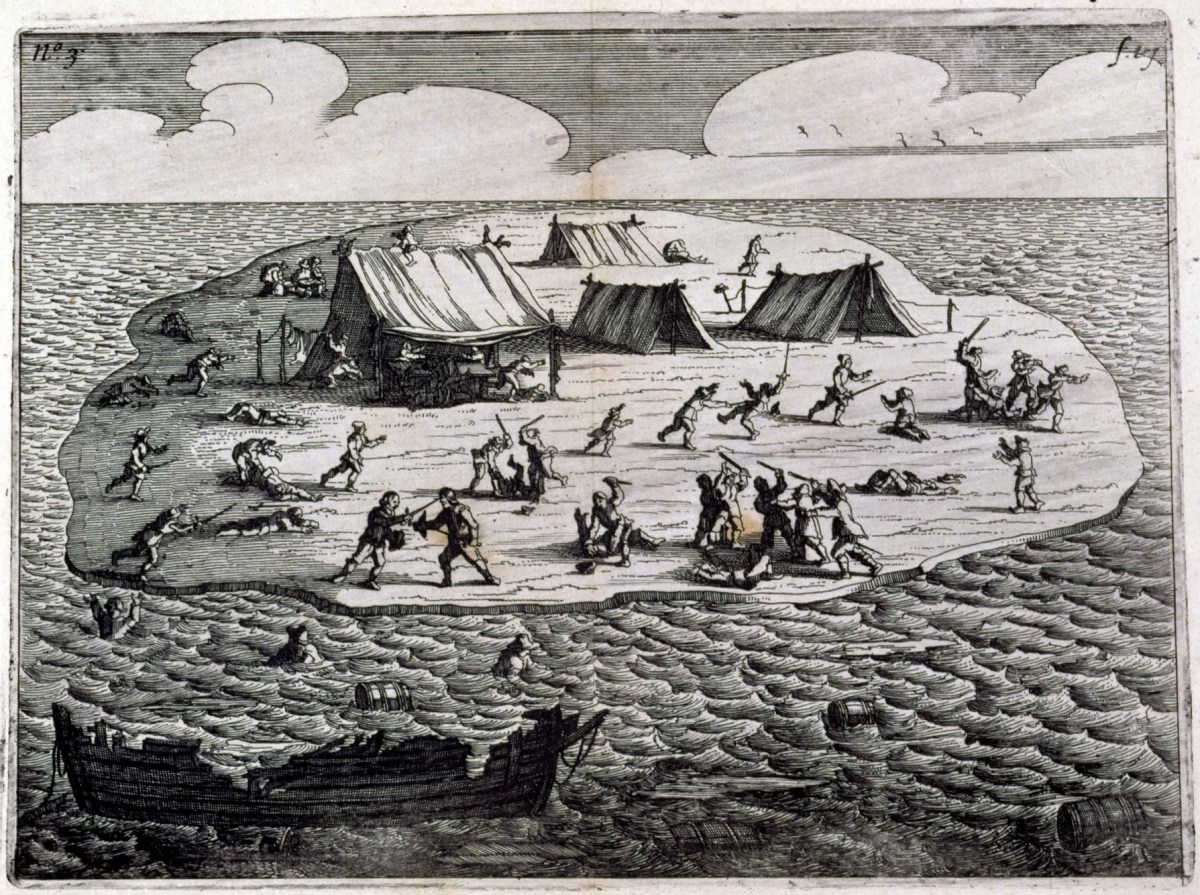

Indigenous nations of the time divided more along ethnic and linguistic rather than political lines, so there was no monolithic policy among the tribes. At least one British fort was taken with profuse apologies by the Indians, who explained that it was the other nations making them do it.

Indigenous nations of the time divided more along ethnic and linguistic rather than political lines, so there was no monolithic policy among the tribes. At least one British fort was taken with profuse apologies by the Indians, who explained that it was the other nations making them do it.

Some sixty to eighty Ohio valley Indians died of the disease following the Fort Pitt episode, but the outbreak appears isolated. Meanwhile, Indian warriors had looted clothing from some 2,000 outlying settlers they had killed or abducted.

Some sixty to eighty Ohio valley Indians died of the disease following the Fort Pitt episode, but the outbreak appears isolated. Meanwhile, Indian warriors had looted clothing from some 2,000 outlying settlers they had killed or abducted.

The British Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763, drew a line between the British colonies and Indian lands, creating a vast Indian Reserve stretching from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River and from Florida to Newfoundland. For the Indian Nations, this was the first time that a multi-tribal effort had been launched against British expansion, the first time such an effort had not ended in defeat.

The British Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763, drew a line between the British colonies and Indian lands, creating a vast Indian Reserve stretching from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River and from Florida to Newfoundland. For the Indian Nations, this was the first time that a multi-tribal effort had been launched against British expansion, the first time such an effort had not ended in defeat.

It may be hard to imagine but, Canis lupus, the wolf, is the ancestor of the modern dog, Canis familiaris. Every one of them, from Newfoundlands to Chihuahuas.

It may be hard to imagine but, Canis lupus, the wolf, is the ancestor of the modern dog, Canis familiaris. Every one of them, from Newfoundlands to Chihuahuas.

Sus scrofa (the pig) was domesticated around 6000 BC throughout the Middle East and China. Pigs were originally used as draft animals. There are stone engravings depicting teams of hogs hauling war chariots. I wonder what that sounded like.

Sus scrofa (the pig) was domesticated around 6000 BC throughout the Middle East and China. Pigs were originally used as draft animals. There are stone engravings depicting teams of hogs hauling war chariots. I wonder what that sounded like.

Early camelids spread across the Bering land bridge, moving the opposite direction from the Asian immigration to America, surviving in the Old World and eventually becoming domesticated and spreading globally by humans. The first “camelids” became domesticated about 4,500 years ago in Peru: The “New World Camels” the Llama and the Alpaca, and the “South American Camels”, the Guanaco and the Vicuña.

Early camelids spread across the Bering land bridge, moving the opposite direction from the Asian immigration to America, surviving in the Old World and eventually becoming domesticated and spreading globally by humans. The first “camelids” became domesticated about 4,500 years ago in Peru: The “New World Camels” the Llama and the Alpaca, and the “South American Camels”, the Guanaco and the Vicuña.

You must be logged in to post a comment.