In the 5th century, the migration of warlike Germanic tribes across northern Europe culminated in the destruction of the Roman Empire in the west. That much is relatively well known, but the “why”, is not. What would a people so fearsome that they brought down an empire, have been trying to get away from?

The Roman Empire was split in two in the 5th century and ruled by two separate governments. Ravenna, in northern Italy, became capital to the Western Roman Empire in 402, and would remain so until the final collapse in 476. Constantinople, seat of the Byzantine empire and destined to become modern day Istanbul, ruled in the East.

Vast populations moved westward from Germania during the early fifth century, and into Roman territories in the west and south. They were Alans and Vandals, Suebi, Goths, and Burgundians. There were others as well, crossing the Rhine and the Danube and entering Roman Gaul. They came not in conquest: that would come later. These tribes were fleeing the Huns: a people so terrifying that whole tribes agreed to be disarmed, in exchange for the protection of Rome.

Vast populations moved westward from Germania during the early fifth century, and into Roman territories in the west and south. They were Alans and Vandals, Suebi, Goths, and Burgundians. There were others as well, crossing the Rhine and the Danube and entering Roman Gaul. They came not in conquest: that would come later. These tribes were fleeing the Huns: a people so terrifying that whole tribes agreed to be disarmed, in exchange for the protection of Rome.

Rome itself had mostly friendly relations with the Hunnic Empire, which stretched from modern day Germany in the west, to Turkey and most of Ukraine in the east. The Huns were nomads, mounted warriors whose main weapons were the bow and javelin. Huns frequently acted as mercenary soldiers, paid to fight on behalf of Rome.

Rome looked at such payments as just compensation for services rendered. The Huns looked at them as tribute, tokens of Roman submission to the Hunnic Empire.

Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, described Rome’s Hun problem, succinctly. “They have become both masters and slaves of the Romans”.

Relations were strained between the two powers in the time of the Hunnic King Rugila, as his nephew the future King Attila, came of age.

Rugila’s death in 434 left the sons of his brother Mundzuk, Attila and Bleda, in control of the united Hunnic tribes. The brothers negotiated a treaty with Emperor Theodosius of Constantinople the following year, giving him time to strengthen the city’s defenses. This included building the first sea wall, a structure the city would be forced to defend a thousand years later in the Islamic conquest of 1453, but that is a story for another day.

The priest of the Greek church Callinicus wrote what happened next, in his “Life of Saint Hypatius”. “The barbarian nation of the Huns, which was in Thrace, became so great that more than a hundred cities were captured and Constantinople almost came into danger and most men fled from it. … And there were so many murders and blood-lettings that the dead could not be numbered. Ay, for they took captive the churches and monasteries and slew the monks and maidens in great numbers“.

Bleda died sometime in 445, leaving Attila the sole King of the Huns. Relations with the Western Roman Empire had been relatively friendly, for a time. That changed in 450 when Justa Grata Honoria, sister of Emperor Valentinian, wanted to escape a forced marriage to the former consul Herculanus. Honoria sent the eunuch Hyacinthus with a note to King Attila, asking him to intervene on her behalf. She enclosed her ring in token of the message’s authenticity, which Attila took to be an offer of marriage.

Valentinian was furious with his sister. Only the influence of their mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile rather than have her put to death, while he frantically wrote to Attila saying it was all a misunderstanding.

Valentinian was furious with his sister. Only the influence of their mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile rather than have her put to death, while he frantically wrote to Attila saying it was all a misunderstanding.

The King of the Huns wasn’t buying it, and sent an emissary to Ravenna, to claim what was his. Attila demanded delivery of his “bride”, along with half the empire, as dowry.

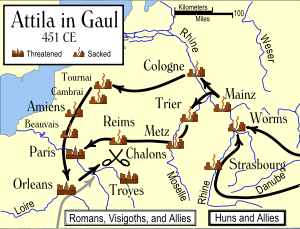

In 451, Attila gathered his vassals and began a march to the west. The Hunnic force was estimated to be half a million strong, though the number is probably exaggerated. The Romans hurriedly gathered an army to oppose them, while the Huns sacked the cities of Mainz, Worms and Strasbourg. Trier and Metz fell in quick succession, as did Cologne, Cambrai, and Orleans.

The Roman army, allied with the Visigothic King Theodoric I, finally stopped the army of Attila at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, near Chalons. Some sources date the Battle of Chalons at June 20, 451, others at September 20. Even the outcome of the battle is open to interpretation. Sources may be found to support the conclusion that it was a Roman, a Gothic or a Hunnic victory.

Apparently a Pyrrhic victory, Chalons was one of the last major military operations of the Roman Empire in the west. The Roman alliance had stopped the Hunnic invasion in Gaul, but the military capacity of Roman and Visigoth, both, was destroyed. The Hunnic Empire was dismantled by a coalition of Germanic vassals at the Battle of Nedau, in 454.

Attila would return to sack much of Italy in 452, this time razing Aquileia so completely that no trace of it was left behind. Legend has it that Venice was founded at this time, when local residents fled the Huns, taking refuge in the marshes and islands of the Venetian Lagoon.

Attila died the following year at a wedding feast, celebrating his marriage to the young Ostrogoth, Ildico. The King of the Huns died in a drunken stupor, suffering a massive nosebleed or possibly esophageal bleeding. The Hunnic Empire died along with Attila the Hun, as he choked to death on his own blood.

The story begins with Jefferson Davis, in the 1840s. Now we remember him as the President of the Confederate States of America. Then, he was a United States Senator from Mississippi, with a pet project of introducing camels into the United States.

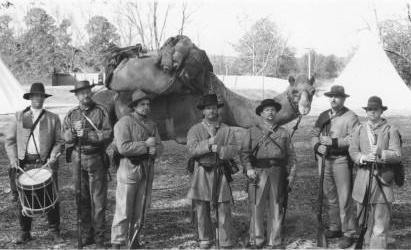

The story begins with Jefferson Davis, in the 1840s. Now we remember him as the President of the Confederate States of America. Then, he was a United States Senator from Mississippi, with a pet project of introducing camels into the United States. The measure failed, but in the 1850s, then-Secretary of War Davis persuaded President Franklin Pierce that camels were the military super weapons of the future. Able to carry greater loads over longer distances than any other pack animal, Davis saw camels as the high tech weapon of the age. Hundreds of horses and mules were dying in the hot, dry conditions of Southwestern Cavalry outposts, when the government purchased 75 camels from Algeria, Tunisia and Egypt. Several camel handlers came along in the bargain, one of them a Syrian named Haji Ali, who successfully implemented a camel breeding program. Haji Ali became quite the celebrity within the West Texas outpost. The soldiers called him “Hi Jolly”.

The measure failed, but in the 1850s, then-Secretary of War Davis persuaded President Franklin Pierce that camels were the military super weapons of the future. Able to carry greater loads over longer distances than any other pack animal, Davis saw camels as the high tech weapon of the age. Hundreds of horses and mules were dying in the hot, dry conditions of Southwestern Cavalry outposts, when the government purchased 75 camels from Algeria, Tunisia and Egypt. Several camel handlers came along in the bargain, one of them a Syrian named Haji Ali, who successfully implemented a camel breeding program. Haji Ali became quite the celebrity within the West Texas outpost. The soldiers called him “Hi Jolly”.

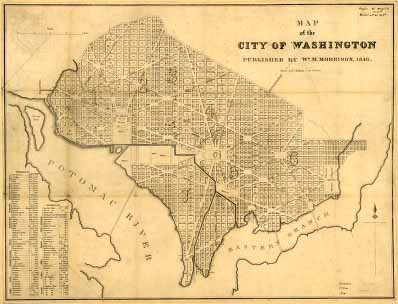

The “Residence Act” of July 1790 established the Federal government along the banks of the Potomac River. The specific site had been up for debate, before Alexander Hamilton brokered a compromise. Several delegates switched support in favor of the current location, in exchange for the Federal government assuming their states’ war debt.

The “Residence Act” of July 1790 established the Federal government along the banks of the Potomac River. The specific site had been up for debate, before Alexander Hamilton brokered a compromise. Several delegates switched support in favor of the current location, in exchange for the Federal government assuming their states’ war debt.

Funding problems and design squabbles plagued the project from the beginning. The building was incomplete when Congress held its first session there on November 17, 1800.

Funding problems and design squabbles plagued the project from the beginning. The building was incomplete when Congress held its first session there on November 17, 1800.

By the 1850s, the number of new states’ representatives threatened to exceed the building’s designed capacity. President Millard Fillmore held a design competition, resulting in the House and Senate wings as you see them today.

By the 1850s, the number of new states’ representatives threatened to exceed the building’s designed capacity. President Millard Fillmore held a design competition, resulting in the House and Senate wings as you see them today.

Germany needed air supremacy before “Operation Sea Lion”, the amphibious invasion of England, could begin. Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring said he would have it in four days.

Germany needed air supremacy before “Operation Sea Lion”, the amphibious invasion of England, could begin. Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring said he would have it in four days.

Czechoslovakia fell to the Nazis on the Ides of March, 1939, Czech armed forces having been ordered to offer no resistance. Some 4,000 Czech soldiers and airmen managed to get out, most escaping to neighboring Poland.

Czechoslovakia fell to the Nazis on the Ides of March, 1939, Czech armed forces having been ordered to offer no resistance. Some 4,000 Czech soldiers and airmen managed to get out, most escaping to neighboring Poland.

British military authorities were slow to recognize the flying skills of the Polskie Siły Powietrzne (Polish Air Forces), the first fighter squadrons only seeing action in the third phase of the Battle of Britain. Despite the late start, Polish flying skills proved superior to those of less-experienced Commonwealth pilots. The 303rd Polish fighter squadron became the most successful RAF fighter unit of the period, its most prolific flying ace being Czech Sergeant Josef František. He was killed in action in the last phase of the Battle of Britain, the day after his 26th birthday.

British military authorities were slow to recognize the flying skills of the Polskie Siły Powietrzne (Polish Air Forces), the first fighter squadrons only seeing action in the third phase of the Battle of Britain. Despite the late start, Polish flying skills proved superior to those of less-experienced Commonwealth pilots. The 303rd Polish fighter squadron became the most successful RAF fighter unit of the period, its most prolific flying ace being Czech Sergeant Josef František. He was killed in action in the last phase of the Battle of Britain, the day after his 26th birthday.

Mad Jack was sent off to Burma, following the defeat of Nazi Germany. He was disappointed by the swift end to the war brought about by the American bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, saying “If it wasn’t for those damn Yanks, we could have kept the war going another 10 years!”

Mad Jack was sent off to Burma, following the defeat of Nazi Germany. He was disappointed by the swift end to the war brought about by the American bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, saying “If it wasn’t for those damn Yanks, we could have kept the war going another 10 years!”

Leonardo da Vinci drew sketches of a man-powered, wheeled vehicle encased in armor and bristling with cannon, as early as the 15th century. The design was limited, since no human crew could generate enough power to move it for long, and the use of animals in such confined spaces was fraught with problems..

Leonardo da Vinci drew sketches of a man-powered, wheeled vehicle encased in armor and bristling with cannon, as early as the 15th century. The design was limited, since no human crew could generate enough power to move it for long, and the use of animals in such confined spaces was fraught with problems..

With no suspension, the bone jarring ride on one of these monsters was just the beginning of what crews were forced to endure.

With no suspension, the bone jarring ride on one of these monsters was just the beginning of what crews were forced to endure.

The documents came from Lt. Col. Bill Burkett, a former Texas Army National Guard officer who had received publicity back in 2000, when he claimed to have been transferred to Panama after refusing to falsify then-Governor Bush’s personnel records. He later retracted the claim, but popped up again during the 2004 election cycle. Many considered Burkett to be an “anti-Bush zealot”.

The documents came from Lt. Col. Bill Burkett, a former Texas Army National Guard officer who had received publicity back in 2000, when he claimed to have been transferred to Panama after refusing to falsify then-Governor Bush’s personnel records. He later retracted the claim, but popped up again during the 2004 election cycle. Many considered Burkett to be an “anti-Bush zealot”. The New York Times interviewed Marian Carr Knox who’d been secretary to the squadron in 1972, running a story dated September 14 under the bylines of Maureen Balleza and Kate Zernike. The headline read “Memos on Bush Are Fake but Accurate, Typist Says“.

The New York Times interviewed Marian Carr Knox who’d been secretary to the squadron in 1972, running a story dated September 14 under the bylines of Maureen Balleza and Kate Zernike. The headline read “Memos on Bush Are Fake but Accurate, Typist Says“. Public confidence in the “Mainstream Media” plummeted. Many saw the episode as a news network lying, and the “Newspaper of Record” swearing to it.

Public confidence in the “Mainstream Media” plummeted. Many saw the episode as a news network lying, and the “Newspaper of Record” swearing to it.

a nostalgic period looking back to the Classical age. Whatever it was, the 15th and 16th centuries produced some of the most spectacularly gifted artists, in history.

a nostalgic period looking back to the Classical age. Whatever it was, the 15th and 16th centuries produced some of the most spectacularly gifted artists, in history.

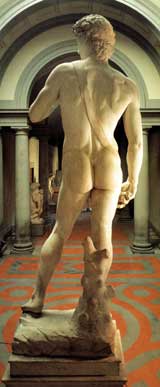

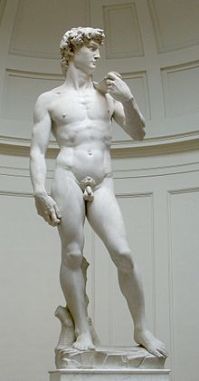

The massive block of Carrara marble was quarried in 1466, nine years before Michelangelo was born. The “David” commission was given to artist Agostino di Duccio that same year. So difficult was this particular marble block that he never got beyond roughing out the legs and draperies. Antonio Rossellino took a shot at it 10 years later, but he didn’t get much farther.

The massive block of Carrara marble was quarried in 1466, nine years before Michelangelo was born. The “David” commission was given to artist Agostino di Duccio that same year. So difficult was this particular marble block that he never got beyond roughing out the legs and draperies. Antonio Rossellino took a shot at it 10 years later, but he didn’t get much farther. Cathedral, but it wasn’t feasible to raise such an object that high. A committee including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli was formed to decide on an appropriate site for the statue. The commitee chose the Piazza della Signoria outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the town hall of Florence.

Cathedral, but it wasn’t feasible to raise such an object that high. A committee including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli was formed to decide on an appropriate site for the statue. The commitee chose the Piazza della Signoria outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the town hall of Florence.

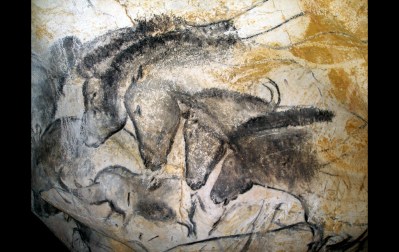

The Lascaux Caves are located in the Dordogne region, in Southwestern France. Some 17,000 years ago, Upper Paleolithic artists mixed mineral pigments such as iron oxide (ochre), haematite, and goethite, suspending pigments in animal fat, clay or the calcium-rich groundwater of the caves themselves. Shading and depth were added with charcoal.

The Lascaux Caves are located in the Dordogne region, in Southwestern France. Some 17,000 years ago, Upper Paleolithic artists mixed mineral pigments such as iron oxide (ochre), haematite, and goethite, suspending pigments in animal fat, clay or the calcium-rich groundwater of the caves themselves. Shading and depth were added with charcoal. The artist or artists who created such images, nearly 2,000 of them occupying some 37 chambers, would have been recognizable as modern humans. Living as they did some 5,000 years before the Holocene Glacial Retreat, (yes, they had “climate change” back then), these cave-dwellers were pre-agricultural, subsisting on what they could find, or what they could kill.

The artist or artists who created such images, nearly 2,000 of them occupying some 37 chambers, would have been recognizable as modern humans. Living as they did some 5,000 years before the Holocene Glacial Retreat, (yes, they had “climate change” back then), these cave-dwellers were pre-agricultural, subsisting on what they could find, or what they could kill. The purpose served by these images is unclear. Perhaps they tell stories of past hunts, or maybe they were used to call up the spirits for a successful hunt. At least one professor of art and archaeology postulates that the dot and lattice patterns overlying many of these paintings may reflect trance visions, similar to the hallucinations produced by sensory deprivation.

The purpose served by these images is unclear. Perhaps they tell stories of past hunts, or maybe they were used to call up the spirits for a successful hunt. At least one professor of art and archaeology postulates that the dot and lattice patterns overlying many of these paintings may reflect trance visions, similar to the hallucinations produced by sensory deprivation.

Graduating from UMass Lowell in 1972 with a degree in nuclear engineering, John Ogonowski joined the United States Air Force. During the war in Vietnam, the farmer-turned-pilot would ferry equipment from Charleston, South Carolina to Southeast Asia, sometimes returning with the bodies of the fallen aboard his C-141 transport aircraft.

Graduating from UMass Lowell in 1972 with a degree in nuclear engineering, John Ogonowski joined the United States Air Force. During the war in Vietnam, the farmer-turned-pilot would ferry equipment from Charleston, South Carolina to Southeast Asia, sometimes returning with the bodies of the fallen aboard his C-141 transport aircraft. Ogonowski helped to create the Dracut Land Trust in 1998, working to conserve the town’s agricultural heritage. He worked to bring more people into farming, as well. The bumper sticker on his truck read “There is no farming without farmers”.

Ogonowski helped to create the Dracut Land Trust in 1998, working to conserve the town’s agricultural heritage. He worked to bring more people into farming, as well. The bumper sticker on his truck read “There is no farming without farmers”. It was a natural fit. Ogonowski felt a connection to these people, based on his time in Vietnam. He would help them, here putting up a shed, there getting a greenhouse in order or putting up irrigation. He would help these immigrants, just as those Yankee farmers of long ago, had helped his twice-great grandfather.

It was a natural fit. Ogonowski felt a connection to these people, based on his time in Vietnam. He would help them, here putting up a shed, there getting a greenhouse in order or putting up irrigation. He would help these immigrants, just as those Yankee farmers of long ago, had helped his twice-great grandfather. The program was a success. Ogonowski told The Boston Globe in 1999, “These guys are putting more care and attention into their one acre than most Yankee farmers put into their entire 100 acres.”

The program was a success. Ogonowski told The Boston Globe in 1999, “These guys are putting more care and attention into their one acre than most Yankee farmers put into their entire 100 acres.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.