Military forces of the Japanese Empire appeared unstoppable in the early months of WWII, attacking first Thailand, then the British possessions of Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong, as well as American military bases in Hawaii, Wake Island, Guam and the Philippines.

The United States was grotesquely unprepared to fight a World War in 1942, and dedicated itself to beating Adolf Hitler, first. General Douglas MacArthur abandoned the “Alamo of the Pacific” on March 11 saying “I shall return”, leaving 90,000 American and Filipino troops without food, supplies or support with which to fight off the Japanese offensive.

That April, 75,000 surrendered the Bataan peninsula, beginning a 65-mile, five-day slog into captivity through the heat of the Philippine jungle. Japanese guards were sadistic, beating marchers at random and bayoneting those too weak to walk. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, thousands perished in what came to be known as the Bataan Death March.

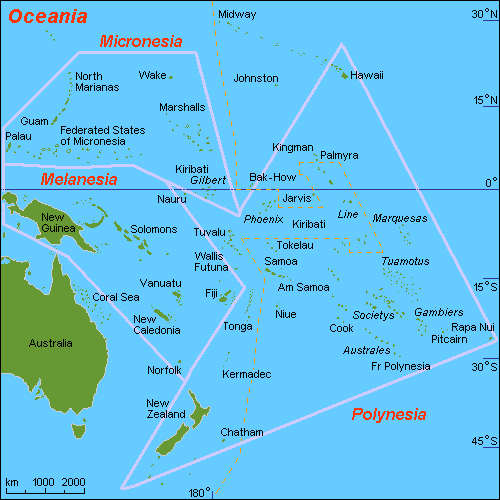

The Imperial Japanese Navy asserted control over much of the region in 1941, installing troop garrisons in the Marshall Island chain and across the ‘biogeographical region’ known as Oceana.

The “Island hopping strategy” used to wrest control of the Pacific islands from the Japanese would prove successful in the end but, in 1942, the Americans had much to learn about this style of warfare.

Today, the island Republic of Kiribati comprises 32 atolls and reef islands, located near the equator in the central Pacific, among a widely scattered group of federated states known as Micronesia. Home to just over 110,000 permanent residents, about half of these live on Tarawa Atoll. At the opposite end of this small archipelago is Butaritari, once known as Makin Island.

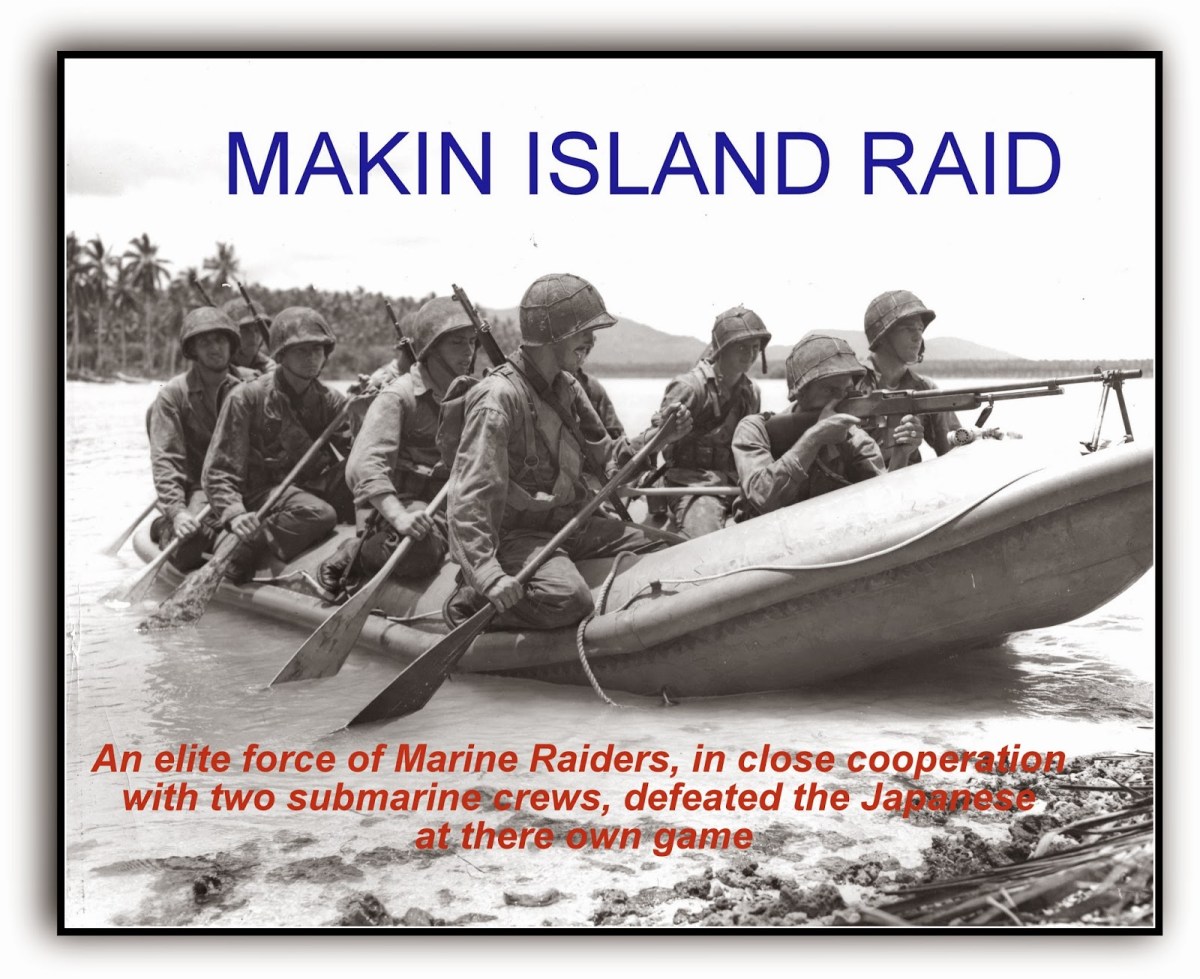

A few minutes past 00:00 (midnight) on August 17, 1942, 211 United States Marine Corps raiders designated Task Group 7.15 (TG 7.15) disembarked from the submarines Argonaut and Nautilus, and boarded inflatable rubber boats for the landing on Makin Island. The raid was among the first major American offensive ground combat operations of WW2, with the objectives of destroying Japanese installations, taking prisoners to gain intelligence on the Gilbert Islands region, and to divert Japanese reinforcement from allied landings at Guadalcanal and Tulagi.

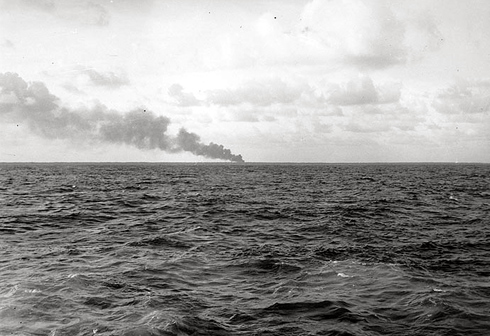

Left), Makin Island as seen by Nautilus and, Right), Marine raiders about to embark

High surf and the failure of several outboard engines confused the night landing. Lt. Colonel Evans Carlson in charge of the raid, decided to land all his men on one beach instead of two as originally planned, but not everyone got the word. At 5:15, a 12-man squad led by Lt. Oscar Peatross found itself isolated and alone but, undeterred by the lack of support, began to move inland in search of the enemy. Meanwhile, the balance of TG 7.15 advanced inland from the landing, encountering strong resistance from Japanese snipers and machine guns.

Two Bansai charges turned out to be a tactical mistake for Japanese forces. Meanwhile, Peatross and his small force of 12 found themselves behind the Japanese machine gun team engaging their fellow Marines. Peatross’ unit killed eight enemy soldiers along with garrison commander Sgt. Major Kanemitsu, knocked out a machine gun and destroyed several enemy radios, while suffering three dead and two wounded of their own.

Unable to contact Carlson, what remained of Peatross’ small band withdrew to the submarines, as originally planned. That was about the last thing that went according to plan.

At 13:30, twelve Japanese aircraft arrived over Makin, including two “flying boats”, carrying reinforcements for the Japanese garrison. Ten aircraft bombed and strafed as the flying boats attempted to land, but both were destroyed in a hail of machine gun and anti-tank fire.

The raiders began to withdraw at 19:30, but surf conditions were far stronger than expected. Ninety-three men managed to struggle back to the waiting submarines, but eleven out of eighteen boats were forced to turn back. Despite hours of heroic effort, exhausted survivors struggled back to the beach, most now without their weapons or equipment.

Wet, dispirited and unarmed, seventy-two exhausted men were now left alone on the island, including only 20 fully-armed Marines originally left behind, to cover the withdrawal.

A Japanese messenger was dispatched to the enemy commander with offer to surrender, but this man was shot by other Marines, unaware of his purpose. A rescue boat was dispatched on the morning of the 18th to stretch a rescue line out to the island. The craft was attacked and destroyed by enemy aircraft. Both subs had to crash dive for the bottom where each was forced to wait out the day. Meanwhile, exhausted survivors fashioned a raft from three remaining rubber boats and a few native canoes, and battled the four miles out of Makin Lagoon, back to the waiting subs. The last survivor was withdrawn at fifty-two minutes before midnight, on August 18.

Many survivors got out with little but their underclothes, and a few souvenirs

The raid annihilated the Japanese garrison on Makin Island, but failed in its other major objectives. In the end, Marines had asked the island people to bury their dead. There had been no time. Casualties at the time were recorded as eighteen killed and 12 missing in action.

The war in the Pacific continued for another three years, but the Butaritari people never forgot the barbarity of the Japanese occupier, nor the Marines who had given their lives in the attempt to throw them out.

Neither it turns out, had one Butaritari elder who, as a teenager, had helped give nineteen dead Marines a warrior’s last due. In December 1999, representatives of the Marine Corps once again came to Butaritari island, not with weapons this time, but with caskets.

The man spoke no English, save for a single song he had memorized during those two days back in 1942, taught to him by those United States Marines: “From the halls of Montezuma, to the shores of Tripoli…”

Being around newspapers allowed the boy to keep up on events overseas, “I didn’t like Hitler to start with“, he once told a reporter. By age eleven, some of Graham’s cousins had been killed in the war, and the boy wanted to fight.

Being around newspapers allowed the boy to keep up on events overseas, “I didn’t like Hitler to start with“, he once told a reporter. By age eleven, some of Graham’s cousins had been killed in the war, and the boy wanted to fight.

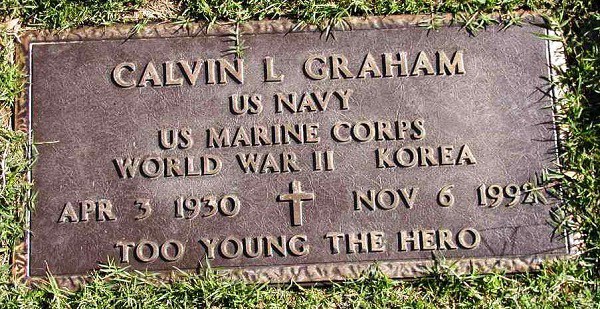

For the rest of his life, Calvin Graham fought for a clean service record, and for restoration of medical benefits. President Jimmy Carter personally approved an honorable discharge in 1978, and all Graham’s medals were reinstated, save for his Purple Heart. He was awarded $337 in back pay but denied medical benefits, save for the disability status conferred by the loss of one of his teeth, back in WW2.

For the rest of his life, Calvin Graham fought for a clean service record, and for restoration of medical benefits. President Jimmy Carter personally approved an honorable discharge in 1978, and all Graham’s medals were reinstated, save for his Purple Heart. He was awarded $337 in back pay but denied medical benefits, save for the disability status conferred by the loss of one of his teeth, back in WW2.

Born and raised in Austria, Greta Zimmer was 16 years old, in 1939. Fearful of the war bearing down on them, Greta’s parents sent her and her two sisters to America, not knowing if they’d ever see each other again.

Born and raised in Austria, Greta Zimmer was 16 years old, in 1939. Fearful of the war bearing down on them, Greta’s parents sent her and her two sisters to America, not knowing if they’d ever see each other again. The couple went to a movie at Radio City Music Hall, but the film was interrupted by a theater employee who turned on the lights, announcing that the war was over. Leaving the theater, the couple joined the tide of humanity moving toward Times Square.

The couple went to a movie at Radio City Music Hall, but the film was interrupted by a theater employee who turned on the lights, announcing that the war was over. Leaving the theater, the couple joined the tide of humanity moving toward Times Square.

Now Eisenstaedt and his Leica Illa rangefinder camera worked for Life Magazine, heading for Times Square in search of “The Picture™”.

Now Eisenstaedt and his Leica Illa rangefinder camera worked for Life Magazine, heading for Times Square in search of “The Picture™”.

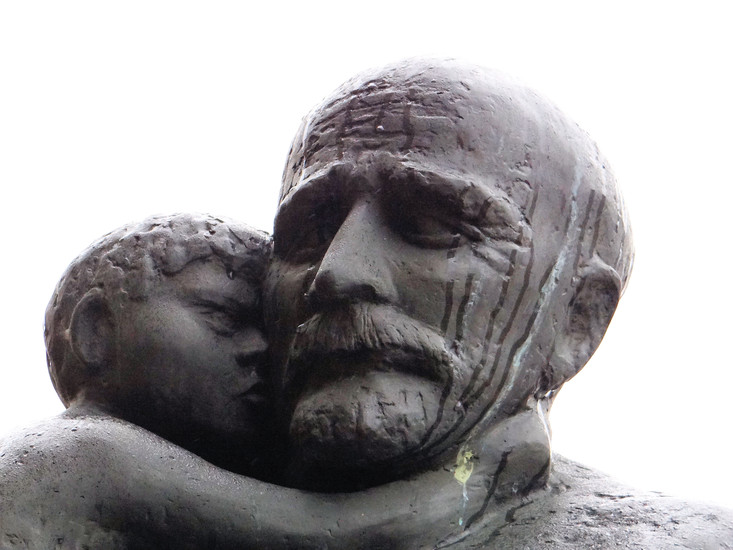

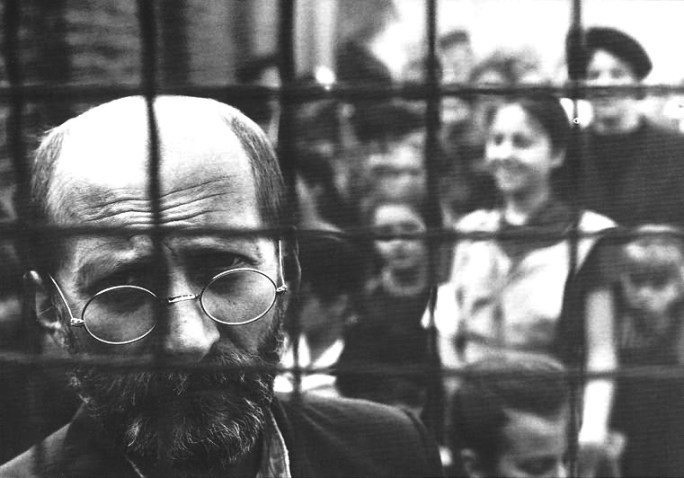

Born Henryk Goldszmit into the Warsaw family of Józef Goldszmit, in 1878 or ’79 (the sources vary), Korczak was the pen name by which he wrote children’s books.

Born Henryk Goldszmit into the Warsaw family of Józef Goldszmit, in 1878 or ’79 (the sources vary), Korczak was the pen name by which he wrote children’s books. Korczak wrote for several Polish language newspapers while studying medicine at the University of Warsaw, becoming a pediatrician in 1904. Always the writer, Korczak received literary recognition in 1905 with his book Child of the Drawing Room (Dziecko salonu), while serving as medical officer during the Russo-Japanese war.

Korczak wrote for several Polish language newspapers while studying medicine at the University of Warsaw, becoming a pediatrician in 1904. Always the writer, Korczak received literary recognition in 1905 with his book Child of the Drawing Room (Dziecko salonu), while serving as medical officer during the Russo-Japanese war.

The Polish nation, the sixth largest in all Europe, was sectioned and partitioned for over a century, by Austrian, Prussian, and Russian imperial powers. Korczak volunteered for military service in 1914, serving as military doctor during WW1 and the series of Polish border wars between 1919-’21.

The Polish nation, the sixth largest in all Europe, was sectioned and partitioned for over a century, by Austrian, Prussian, and Russian imperial powers. Korczak volunteered for military service in 1914, serving as military doctor during WW1 and the series of Polish border wars between 1919-’21.

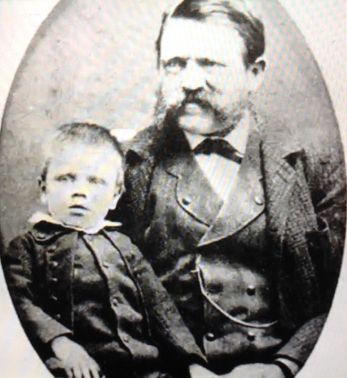

There are plenty of tales regarding the man’s paternity, but none are any more than that. Alois Schicklgruber ‘legitimized’ himself in 1877, adopting a variant on the name of his stepfather and calling himself ‘Hitler”.

There are plenty of tales regarding the man’s paternity, but none are any more than that. Alois Schicklgruber ‘legitimized’ himself in 1877, adopting a variant on the name of his stepfather and calling himself ‘Hitler”.

One such dog was “Chips”, the German Shepherd/Collie/Husky mix who would become the most decorated K-9 of WWII.

One such dog was “Chips”, the German Shepherd/Collie/Husky mix who would become the most decorated K-9 of WWII.

Indeed, such a system has imperfections, not least among them those who would ascend to political office.

Indeed, such a system has imperfections, not least among them those who would ascend to political office.

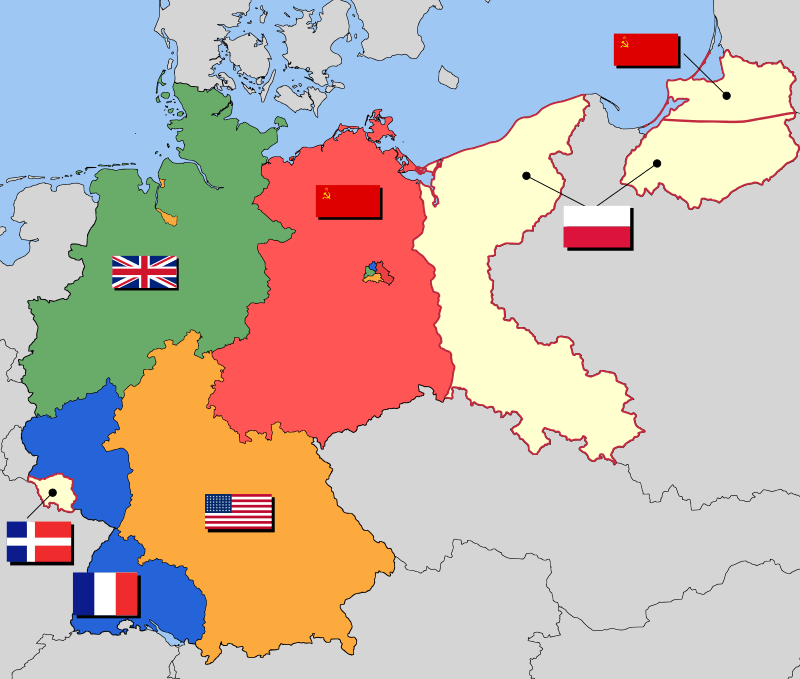

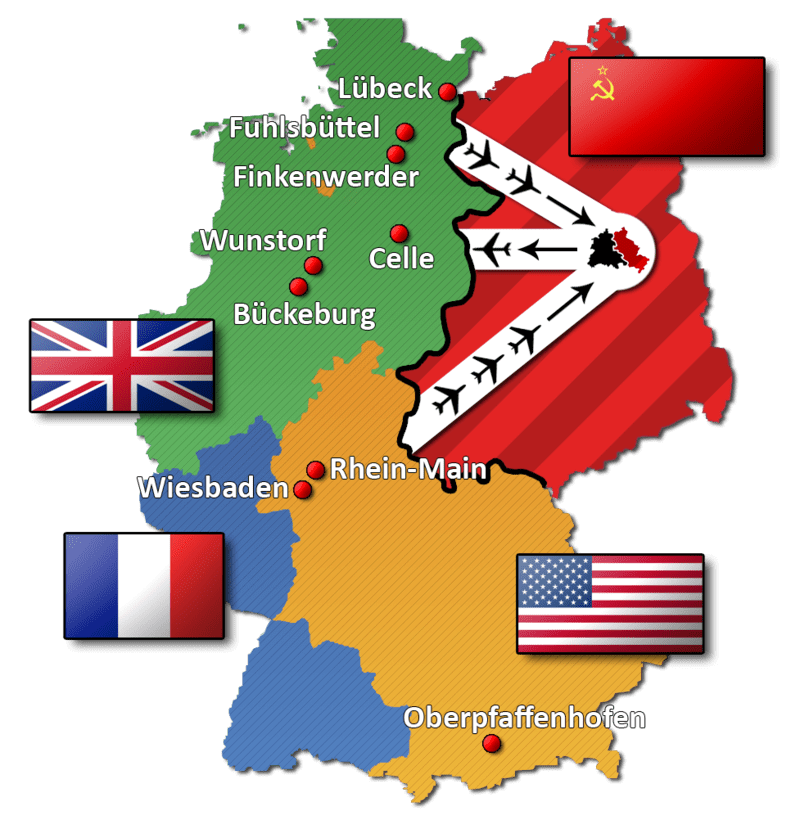

There never was any formal agreement, concerning road and rail access to Berlin through the 100-mile Soviet zone. Western leaders were forced to rely on the “good will” of a regime which had deliberately starved millions of its own citizens to death, in consolidating power.

There never was any formal agreement, concerning road and rail access to Berlin through the 100-mile Soviet zone. Western leaders were forced to rely on the “good will” of a regime which had deliberately starved millions of its own citizens to death, in consolidating power.

The women and children of Oradour-sur-Glane were locked in a village church while German soldiers looted the town. The men were taken to a half-dozen barns and sheds, where the machine guns were already set up.

The women and children of Oradour-sur-Glane were locked in a village church while German soldiers looted the town. The men were taken to a half-dozen barns and sheds, where the machine guns were already set up. Nazi soldiers then lit an incendiary device in the church, and gunned down 247 women and 205 children as they tried to escape.

Nazi soldiers then lit an incendiary device in the church, and gunned down 247 women and 205 children as they tried to escape.

French President Jacques Chirac dedicated a memorial museum in 1999, the “Centre de la mémoire d’Oradour“. The village stands today as those Nazi soldiers left it, seventy-four years ago today. It may be the most forlorn place on earth.

French President Jacques Chirac dedicated a memorial museum in 1999, the “Centre de la mémoire d’Oradour“. The village stands today as those Nazi soldiers left it, seventy-four years ago today. It may be the most forlorn place on earth. a summer day in 1944. . . The soldiers came. Nobody lives here now. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years. . . was dead. This is Oradour-sur-Glane, in France. The day the soldiers came, the people were gathered together. The men were taken to garages and barns, the women and children were led down this road . . . and they were driven. . . into this church. Here, they heard the firing as their men were shot. Then. . . they were killed too. A few weeks later, many of those who had done the killing were themselves dead, in battle. They never rebuilt Oradour. Its ruins are a memorial. Its martyrdom stands for thousands upon thousands of other martyrdoms in Poland, in Russia, in Burma, in China, in a World at War”.

a summer day in 1944. . . The soldiers came. Nobody lives here now. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years. . . was dead. This is Oradour-sur-Glane, in France. The day the soldiers came, the people were gathered together. The men were taken to garages and barns, the women and children were led down this road . . . and they were driven. . . into this church. Here, they heard the firing as their men were shot. Then. . . they were killed too. A few weeks later, many of those who had done the killing were themselves dead, in battle. They never rebuilt Oradour. Its ruins are a memorial. Its martyrdom stands for thousands upon thousands of other martyrdoms in Poland, in Russia, in Burma, in China, in a World at War”.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC. Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

NPR ran an interview about this story back in the eighties, in which an Inupiaq elder was recounting his memories. He had grown up in a world as it existed for hundreds of years, without so much as an idea of internal combustion. He spoke of the day that he first heard the sound of an engine, and went out to see a giant bulldozer making its way over the permafrost. The bulldozer was being driven by a black operator, probably one of the 97th Engineers Battalion soldiers. The old man’s comment, as best I can remember it, was a classic. “It turned out”, he said, “that the first white person I ever saw, was a black man”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.