In an alternate history, the June 1914 assassination of the heir-apparent to the Habsburg Empire may have led to nothing more than a regional squabble. A policing action, in the Balkans.

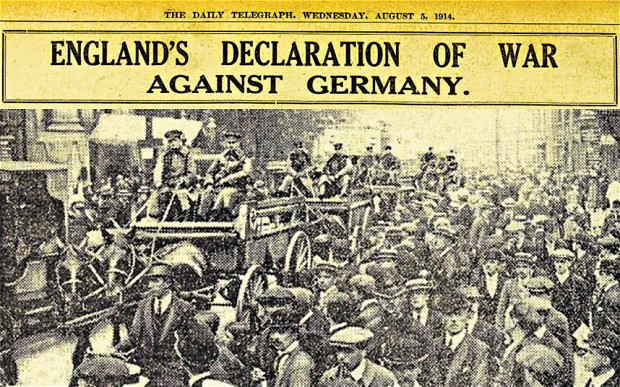

As it was, mutual distrust and entangling alliances combined with slavish obedience to mobilization timetables, to draw the Great Powers of Europe, into the vortex. On August 3, the “War to End All Wars” exploded across the continent.

Many of the soldiers who went off to war in those days, viewed the conflict as some kind of grand adventure. Many of them singing patriotic songs, the men and boys of Russia, Germany, Austria, England and France stealing last kisses from wives and sweethearts, and boarding their ships and trains.

Believing overwhelming manpower to be the key to victory, British Secretary of State for War Lord Horatio Kitchener recruited friends and neighbors by the tens of thousands into “Pal’s Battalions”, to fight for King and country.

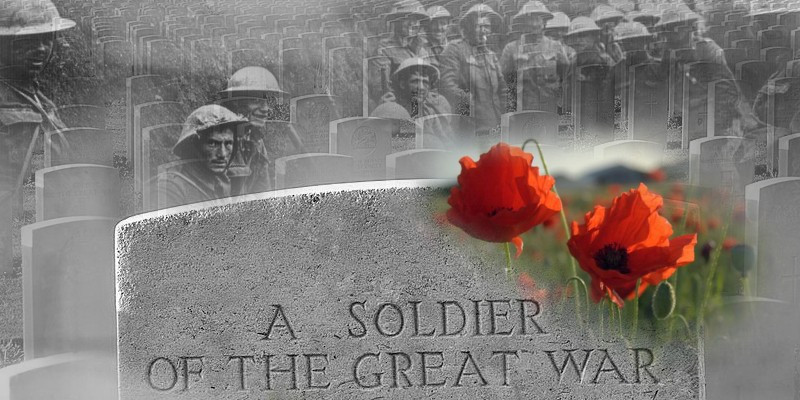

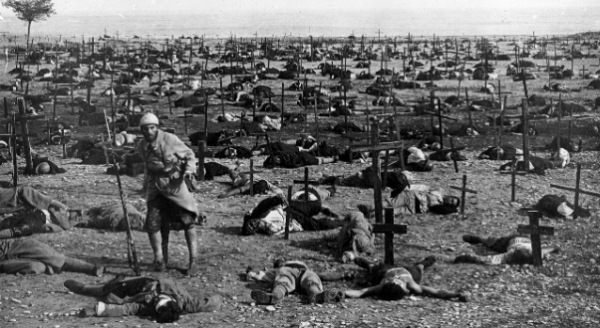

Four years later, a generation had been chewed up and spit out, as if in pieces.

Any single day’s fighting during the great battles of 1916 produced more casualties than every European war of the last 100 years, civilian and military, combined.

As a point of reference, 6,503 Americans lost their lives during the savage, month-long battle for Iwo Jima, in 1945. The first day’s fighting during the 1916 Battle of the Somme, killed three times that number on the British and Commonwealth side, alone.

Over 16 million were killed and another 20 million wounded, while vast stretches of the European countryside were literally, torn to pieces. Tens of thousands of sons, brothers and fathers remain missing, to this day.

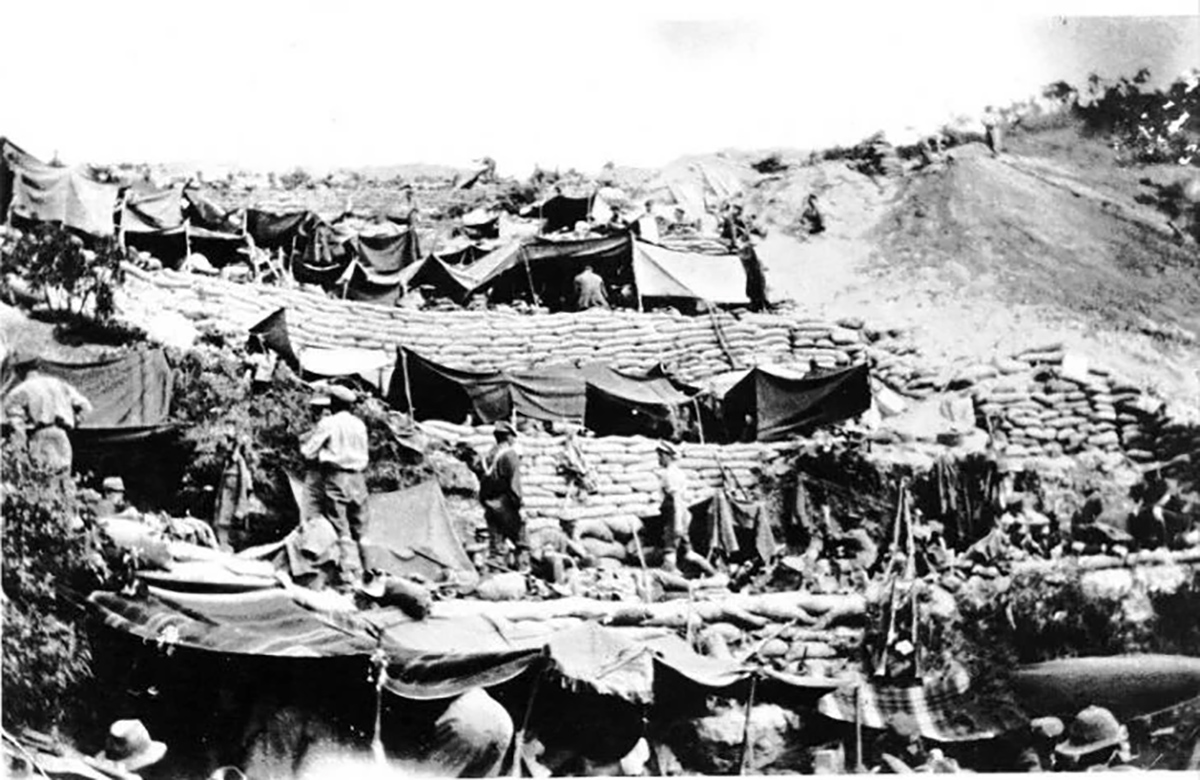

Had you found yourself stuck in the mud and the blood, the rats and the lice of the muddy trenches of New Year 1917-’18, you could have heard a plaintive refrain drifting across the barbed wire and frozen wastes of no man’s land, sung to the tune of ‘Auld Lang Syne”.

We’re here, because we’re here,

because we’re here, because we’re here,

We’re here, because we’re here,

because we’re here, because we’re here.

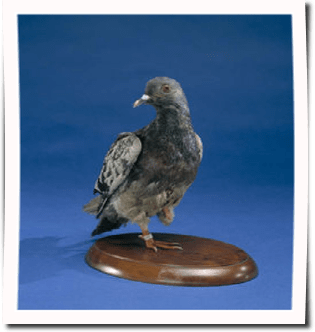

Many of those who fought the “Great War”, weren’t even human. The carrier pigeon Cher Ami escaped a hail of bullets and returned twenty-five miles to her coop despite a sucking chest wound, the loss of an eye and a leg that hung on, by a single tendon. The message she’d been given to carry, saved the lives of 190 men.

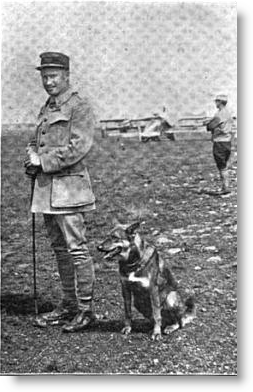

“Warrior” was the thoroughbred mount to General “Galloper” Jack Seely, arriving in August 1914 and serving four years “over there”. “The horse the Germans can’t kill” survived snipers, poison gas and shellfire, twice buried alive in great explosions, only to return home to the Isle of Wight, to live to the ripe old age of 33.

“First Division Rags” ran through a torrent of shells, gassed and blinded in one eye, a shell fragment damaging his front paw and even then, he got his message through.

Jackie the baboon lost a leg during a heavy bombardment from German guns, frantically building a protective rock wall around himself, and his comrades.

Tirpitz the German pig jumped clear of the sinking light cruiser SMS Dresden, only to be rescued in open ocean to become mascot to the HMS Glasgow.

Sixteen million animals served on all sides and in all theaters of WW1: from cats to canaries to pigeons and mules, camels, donkeys and dogs. As “dumb animals”, these were never given the choice to “volunteer”. And yet they served, some nine million making the supreme sacrifice.

In the end, starvation and malnutrition stalked the land at home as well as the front. Riots were rife at home as well as in the trenches. The Russian Empire of the Czars was collapsed into a Bolshevik hellhole, never to return. The domestic economies of nearly every combatant nation was disintegrating, or teetering on the brink.

A strange bugle call came out of the night of November 7, 1918. French soldiers of the 171st Régiment d’Infanterie, stationed near Haudroy, advanced into the the darkness, expecting to be attacked. Instead, the apparitions of three sedans appeared out of the fog, their sides displaying the German Imperial Eagle.

Imperial Germany, its army disintegrating in the field and threatened with revolution at home had sent a peace delegation, headed by 43-year-old politician Matthias Erzberger.

The delegation was escorted to the Compiegne Forest near Paris, to a conference room fashioned from a railroad dining car. There they were met by a delegation headed by Ferdinand Foch, Marshall of France.

The German delegation was stunned at what Foch had to say. ‘Ask these gentlemen what they want,’ he said to his interpreter. Dismayed, Erzberger responded. The German believed they were there to discuss terms of an armistice. Foch dropped the hammer: “Tell these gentlemen that I have no proposals to make”.

Ferdinand Foch had seen his nation destroyed by war, and had vowed “to pursue the Feldgrauen (Field Grays) with a sword at their backs”. He had no intention of letting up.

Marshall Foch now produced a list of 34 demands, each a sledgehammer blow on the German delegation. Germany was to divest herself of all means of self-defense, from her high seas fleet to the last machine gun. She was to withdraw from all lands occupied since 1870. With her population starving at home – the German Board of Public Health claimed a month later, that 763,000 civilians were dead of starvation – the allies were to confiscate 5,000 locomotives, 150,000 rail cars and 5,000 trucks.

Adolf Hitler would gleefully accept French surrender in that same rail car, some twenty-two years later.

By this time, 2,250 combatants were dying every day on the Western Front. Foch informed Ertzberger he had 72 hours in which to respond. “For God’s sake, Monsieur le Marechal”, responded the German, “do not wait for those 72 hours. Stop the hostilities this very day”. The plea fell on deaf ears. Fighting would continue until the last minute, of the last day.

The German King abdicated on November 10, as riots broke out in the streets. The final surrender was signed at 5:10am on November 11, and back-timed to 5:00am Paris time, scheduled to go into effect later that morning. The 11th hour, of the 11th day, of the 11th month.

The order went out. The war would be over in hours, but specific instructions, were few.

Some field commanders ordered their men to stand down. Why fight and die over ground they could walk over, in just a few hours?

Others continued the attack, believing that Germany had to be well and truly beaten. Others saw a last chance at glory, or promotion. One artillery captain named Harry S Truman, kept his battery firing until minutes before 11:00.

English teacher turned Major General Charles Summerall had a fondness for the turn of phrase. Ordering his subordinates across the Meuse River in those final hours, Summerall said “We are swinging the door by its hinges. It has got to move…Get into action and get across. I don’t expect to see any of you again…”

No fewer than 320 Americans were killed in those final six hours, another 3,240 seriously wounded.

Still smarting from the disaster at Mons back in 1914, British High Command was determined to take the place back, on that final day. The British Empire lost more than 2,400 in those last 6 hours.

The French 80th Régiment d’Infanterie received two orders that morning – to launch an attack at 9:00, and cease-fire at 11:00. French losses for the final day amounted to 1,170. The already retreating Germans suffered 4,120.

All sides suffered over 11,000 dead, wounded or missing in those last six hours. Some have estimated that more men died per hour after the armistice was signed, than during the D-Day invasion, some 26 years later.

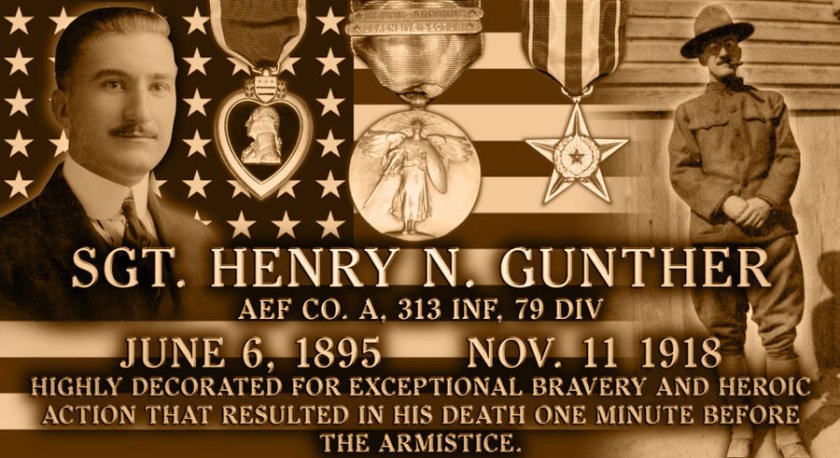

Over in the Meuse-Argonne sector, Henry Gunther was “visibly angry”. Perhaps this American grandson of German immigrants felt he had something to prove. Anti-German bias had not reached levels of the next war, when President Roosevelt interned Americans of Japanese descent, but even so. Such animosity was very real. Gunther’s fiancé had broken the engagement. He’d been busted in rank after that letter home, complaining about conditions.

Bayonet fixed, Gunther charged the German machine gun position, as enemy soldiers frantically waved and yelled for him, to get back. He got off a “shot or two”, before the five round burst tore into his head. Henry Nicholas John Gunther of Baltimore Maryland was the last man to die in combat, in the Great War. It was 10:59am. The war would be over, in sixty seconds.

After eight months on the front lines of France, Corporal Joe Rodier of Worcester Massachusetts, was jubilant. “Another day of days“. Rodier wrote in his diary. “Armistice signed with Germany to take effect at 11 a.m. this date. Great manifestations. Town lighted up at night. Everybody drunk, even to the dog. Moonlight, cool night & not a shot heard“.

Matthias Erzberger was assassinated in 1921, for his role in the surrender. The “Stab in the Back” mythology destined to become Nazi propaganda, had already begun.

AEF Commander General John “Black Jack” Pershing believed the armistice to be a grave error. He believed that Germany had been defeated but not beaten, and that failure to smash the German homeland meant the war would have to be fought, all over again. Ferdinand Foch agreed. On reading the Versailles treaty in 1919, he said “This isn’t peace! This is a truce for 20 years”.

The man got it wrong, by 36 days.

On a personal note:

At sixty-two I still enjoy the memories of a five-year-old, fishing with his grandfather.

PFC Norman Franklin Long was wounded during the Great War, before they had numbers, a member of the United States Army, 33rd Pennsylvania Infantry. He left us on December 18, 1963. A few short hours before his namesake, my brother Norm, was born.

A 1977 fire in the national archives, left us without the means to learn the details of his service.

My father’s father went to his final rest on Christmas eve 1963, in Arlington National Cemetery. Section 41, grave marker 2161.

Rest in peace, Grampa. You left us, too soon.

A female lion, “Soda”, was purchased sometime later. The lions were destined to spend their adult years in a Paris zoo but both remembered from whence they had come. Both animals recognized William Thaw on a later visit to the zoo, rolling onto their backs in expectation of a good belly rub.

A female lion, “Soda”, was purchased sometime later. The lions were destined to spend their adult years in a Paris zoo but both remembered from whence they had come. Both animals recognized William Thaw on a later visit to the zoo, rolling onto their backs in expectation of a good belly rub. Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette.

By 1916 it was generally understood in Germany that the war effort was “shackled to a corpse”, referring the Austro-Hungarian Empire where the war had started, in the first place. Italy, the third member of the “Triple Alliance”, was little better. On the “Triple Entente” side, the French countryside was literally torn to pieces, the English economy close to collapse. The Russian Empire, the largest nation on the planet, was teetering on the edge of the precipice.

By 1916 it was generally understood in Germany that the war effort was “shackled to a corpse”, referring the Austro-Hungarian Empire where the war had started, in the first place. Italy, the third member of the “Triple Alliance”, was little better. On the “Triple Entente” side, the French countryside was literally torn to pieces, the English economy close to collapse. The Russian Empire, the largest nation on the planet, was teetering on the edge of the precipice.

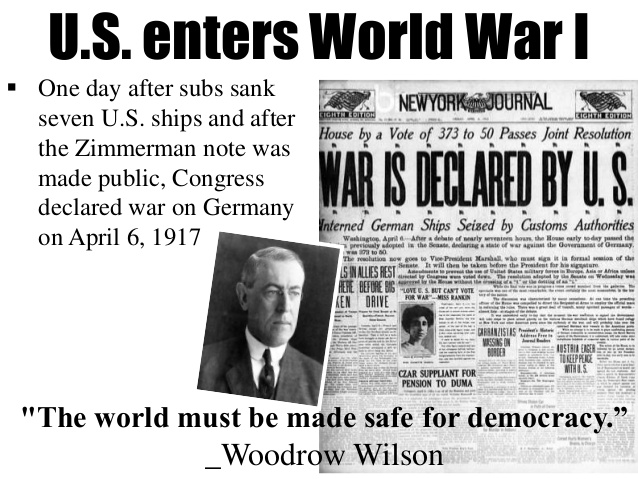

By October, Russia would experience its second revolution of the year. The German Empire could breathe easier. The “Russian Steamroller” was out of the war. And none too soon, too. With the Americans entering the war that April, Chief of the General Staff Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy Erich Ludendorff could now move their divisions westward, in time to face the arrival of the American Expeditionary Force.

By October, Russia would experience its second revolution of the year. The German Empire could breathe easier. The “Russian Steamroller” was out of the war. And none too soon, too. With the Americans entering the war that April, Chief of the General Staff Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy Erich Ludendorff could now move their divisions westward, in time to face the arrival of the American Expeditionary Force.

Some 40 million were killed in the Great War, either that or maimed or simply, vanished. It was a mind bending number, equivalent to the entire population in 1900 of either France, or the United Kingdom. Equal to the combined populations of the bottom two-thirds of every nation on the planet. Every woman, man, puppy, boy and girl.

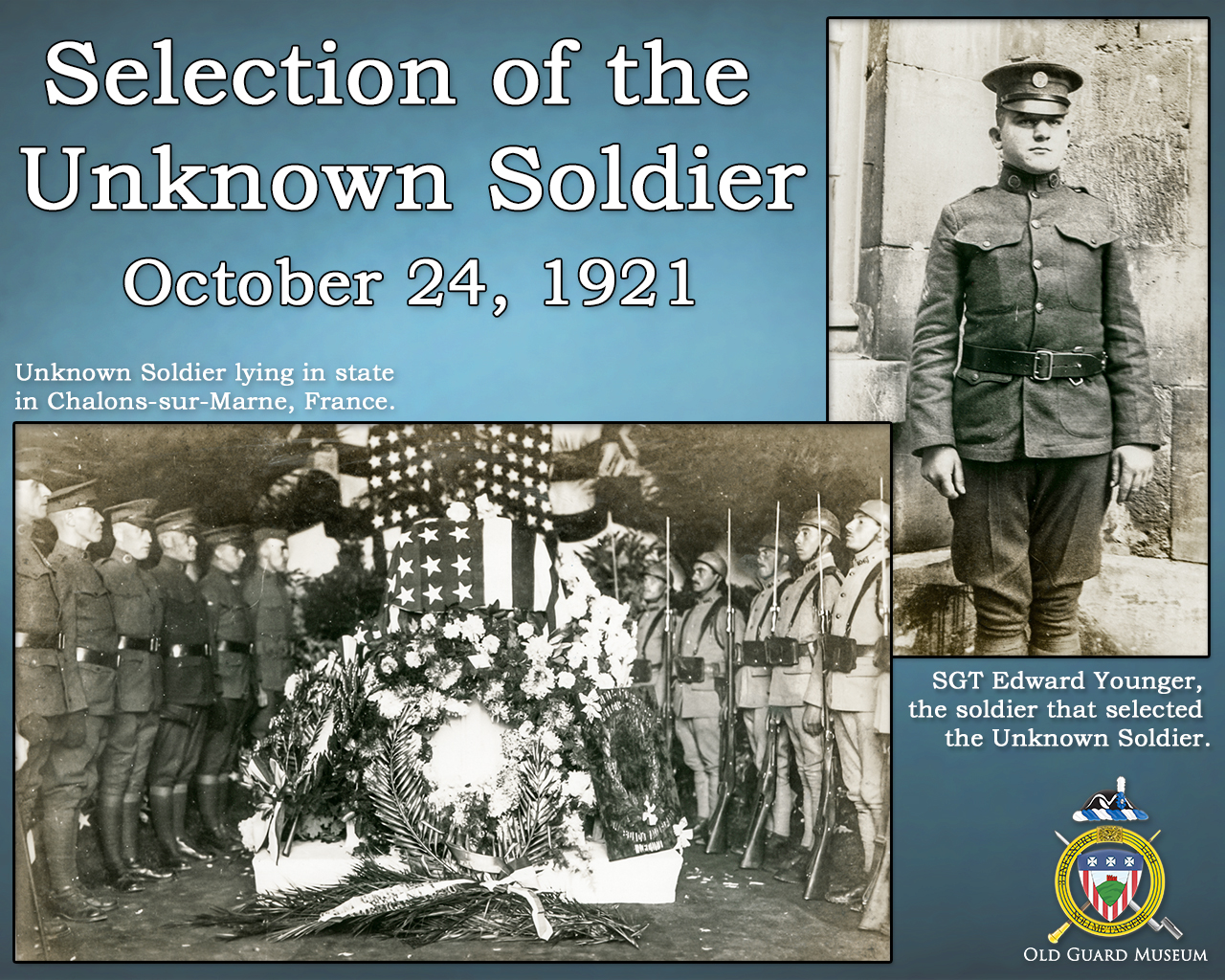

Some 40 million were killed in the Great War, either that or maimed or simply, vanished. It was a mind bending number, equivalent to the entire population in 1900 of either France, or the United Kingdom. Equal to the combined populations of the bottom two-thirds of every nation on the planet. Every woman, man, puppy, boy and girl. The idea of honoring the unknown dead from the “War to end all Wars” originated in Europe. Reverend David Railton remembered a rough cross from somewhere on the western front, with the words written in pencil: “An Unknown British Soldier”.

The idea of honoring the unknown dead from the “War to end all Wars” originated in Europe. Reverend David Railton remembered a rough cross from somewhere on the western front, with the words written in pencil: “An Unknown British Soldier”.

Passing between two lines of French and American officials, Sgt. Younger entered the room, alone. Slowly, he circled the four caskets, three times, before at last stopping at the third from the left. “What caused me to stop” he later said, “I don’t know. It was as though something had pulled me“. Younger placed the roses on the casket, drew himself to attention, and saluted. This was the one.

Passing between two lines of French and American officials, Sgt. Younger entered the room, alone. Slowly, he circled the four caskets, three times, before at last stopping at the third from the left. “What caused me to stop” he later said, “I don’t know. It was as though something had pulled me“. Younger placed the roses on the casket, drew himself to attention, and saluted. This was the one. On November 11, the casket was removed from the Rotunda of the Capitol and escorted under military guard to the amphitheater at

On November 11, the casket was removed from the Rotunda of the Capitol and escorted under military guard to the amphitheater at  With three salvos of artillery, the rendering of Taps and the National Salute, the ceremony was brought to a close and the 12-ton marble cap placed over the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The west facing side bears this inscription:

With three salvos of artillery, the rendering of Taps and the National Salute, the ceremony was brought to a close and the 12-ton marble cap placed over the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The west facing side bears this inscription:

John McCrae was a physician and amateur poet from Guelph, Ontario. Following the outbreak of war in 1914, McCrae enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force at the age of 41. He had the option of joining the medical corps based on his age and training, but volunteered instead to join a fighting unit as gunner and medical officer.

John McCrae was a physician and amateur poet from Guelph, Ontario. Following the outbreak of war in 1914, McCrae enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force at the age of 41. He had the option of joining the medical corps based on his age and training, but volunteered instead to join a fighting unit as gunner and medical officer.

The disaster of the Great War became “Total War” with the zeppelin raids of January, as Endurance met with disaster of its own. The ship was frozen fast, within sight of the Antarctic continent. There was no hope of escape.

The disaster of the Great War became “Total War” with the zeppelin raids of January, as Endurance met with disaster of its own. The ship was frozen fast, within sight of the Antarctic continent. There was no hope of escape.

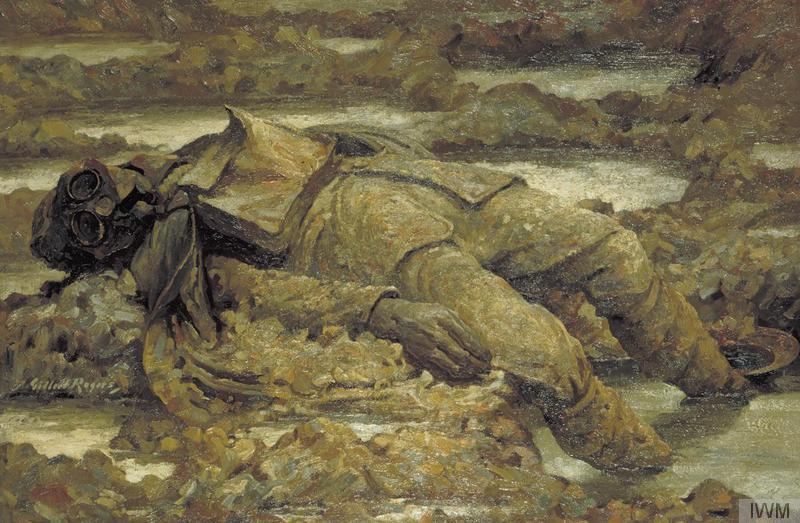

Both sides in the battle for Troy used poisoned arrows, according to the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer. Alexander the great encountered poison arrows and fire weapons in the Indus valley of India, in the fourth century, BC. Chinese chronicles describe an arsenic laden “soul-hunting fog”, used to disperse a peasant revolt, in AD178.

Both sides in the battle for Troy used poisoned arrows, according to the Iliad and the Odyssey of Homer. Alexander the great encountered poison arrows and fire weapons in the Indus valley of India, in the fourth century, BC. Chinese chronicles describe an arsenic laden “soul-hunting fog”, used to disperse a peasant revolt, in AD178. Imperial Germany was first to give serious study to chemical weapons of war, early experiments with irritants taking place at the battle of Neuve-Chapelle in October 1914, and with tear gas at Bolimów on January 31, 1915 and again at Nieuport, that March.

Imperial Germany was first to give serious study to chemical weapons of war, early experiments with irritants taking place at the battle of Neuve-Chapelle in October 1914, and with tear gas at Bolimów on January 31, 1915 and again at Nieuport, that March.

Great Britain possessed massive quantities of mustard, chlorine, Lewisite, Phosgene and Paris Green, awaiting retaliation should Nazi Germany resort to such weapons on the beaches of Normandy. General Alan Brooke, Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces, “[H]ad every intention of using sprayed mustard gas on the beaches” in the event of a German landing on the British home islands.

Great Britain possessed massive quantities of mustard, chlorine, Lewisite, Phosgene and Paris Green, awaiting retaliation should Nazi Germany resort to such weapons on the beaches of Normandy. General Alan Brooke, Commander-in-Chief of the Home Forces, “[H]ad every intention of using sprayed mustard gas on the beaches” in the event of a German landing on the British home islands. The Geneva Protocols on 1925 banned the use of chemical weapons, but not their manufacture, or transport. By 1942, the U.S. Chemical Corps employed some 60,000 soldiers and civilians and controlled a $1 Billion budget.

The Geneva Protocols on 1925 banned the use of chemical weapons, but not their manufacture, or transport. By 1942, the U.S. Chemical Corps employed some 60,000 soldiers and civilians and controlled a $1 Billion budget.

Death comes in days or weeks. Survivors are likely to suffer chronic respiratory disease and infections. DNA is altered, often resulting in certain cancers and birth defects. To this day there is no antidote.

Death comes in days or weeks. Survivors are likely to suffer chronic respiratory disease and infections. DNA is altered, often resulting in certain cancers and birth defects. To this day there is no antidote.

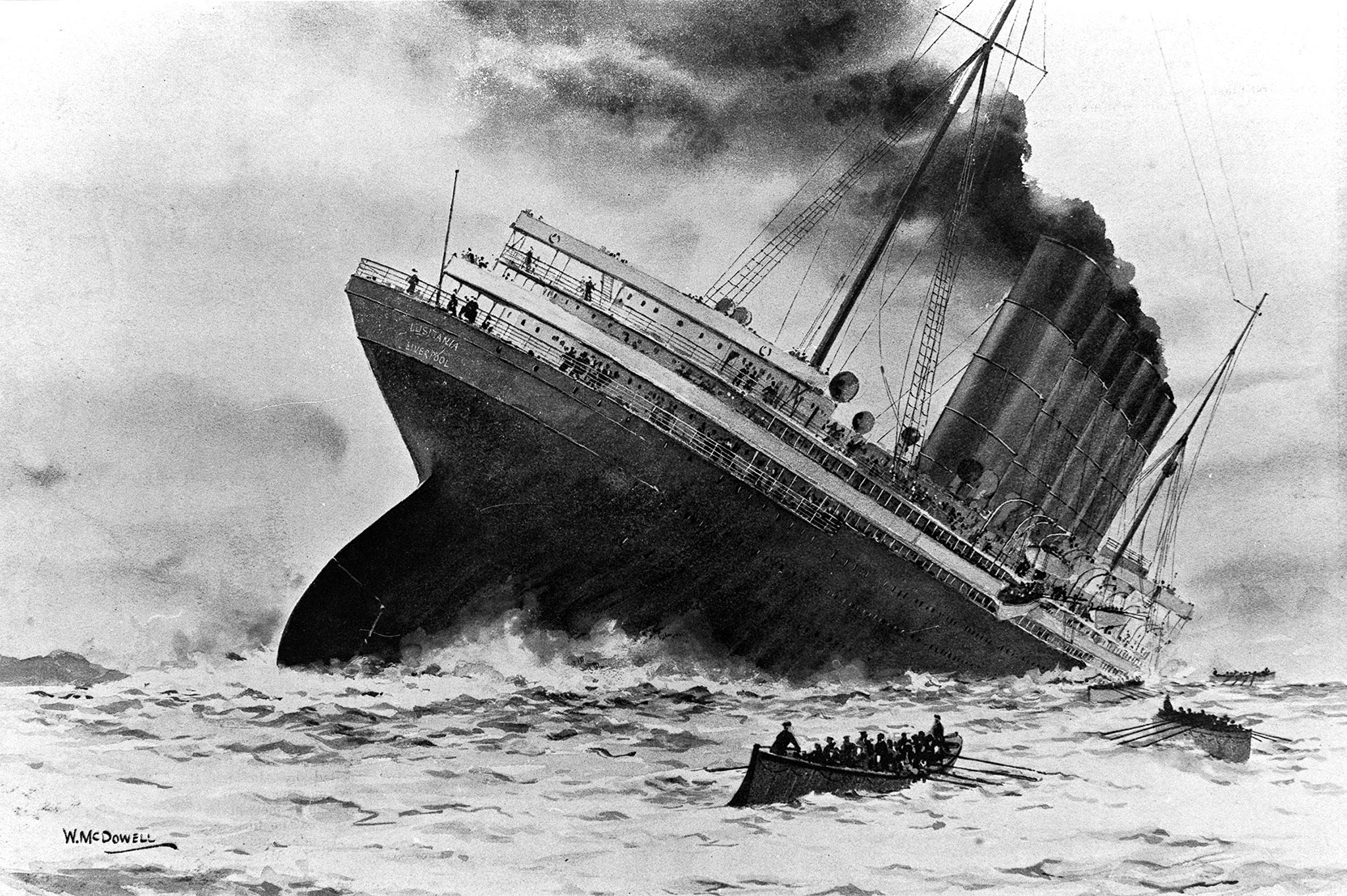

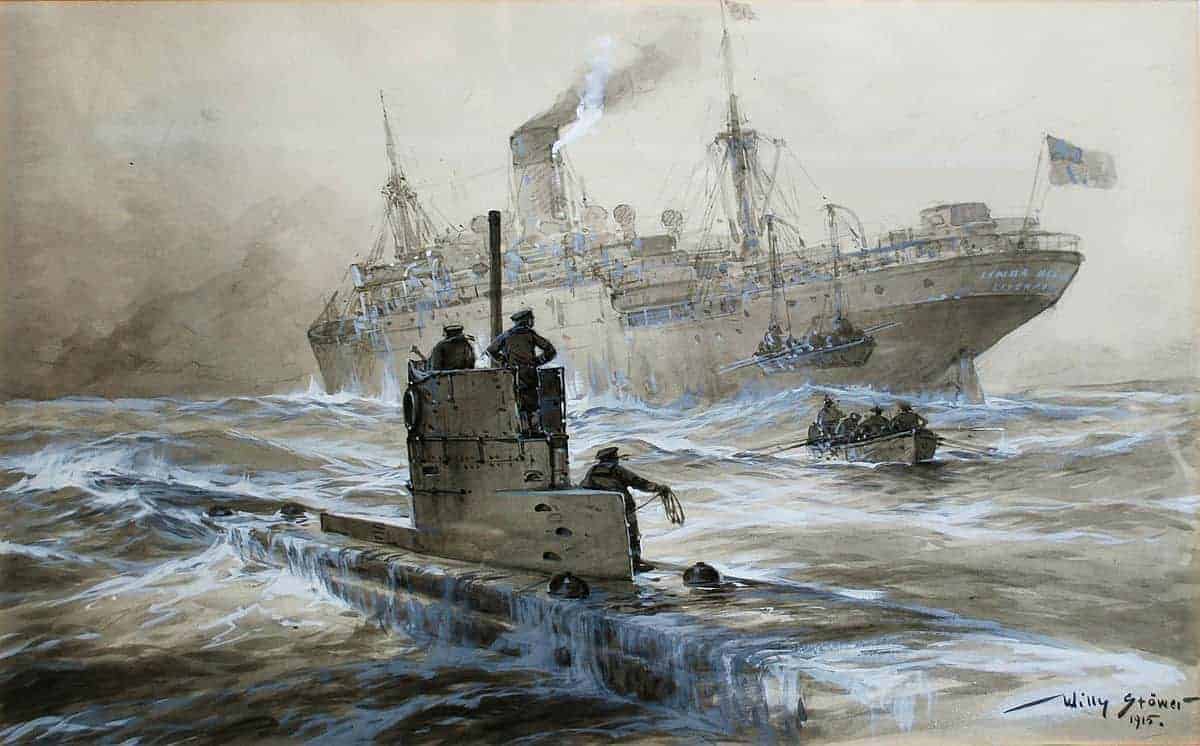

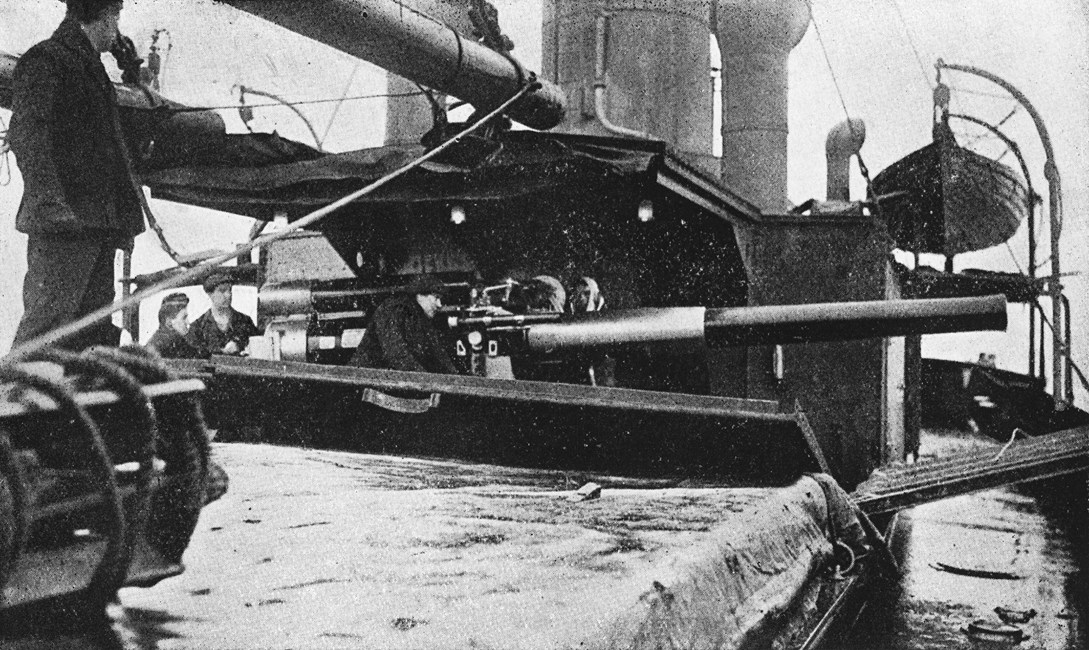

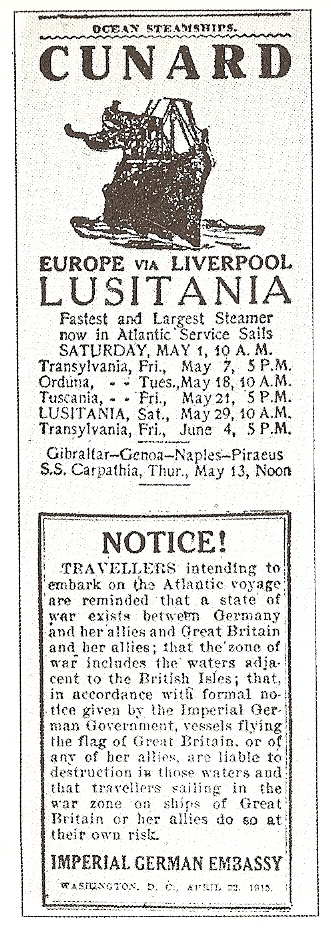

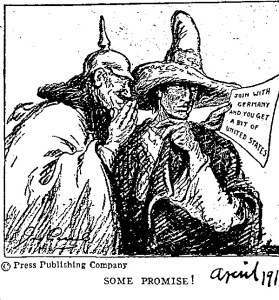

The “Zimmermann Telegram” was intercepted and decoded by British intelligence and revealed to the American government on February 24. The contents of the message outraged American public opinion and helped generate support for the United States’ declaration of war.

The “Zimmermann Telegram” was intercepted and decoded by British intelligence and revealed to the American government on February 24. The contents of the message outraged American public opinion and helped generate support for the United States’ declaration of war.

You must be logged in to post a comment.