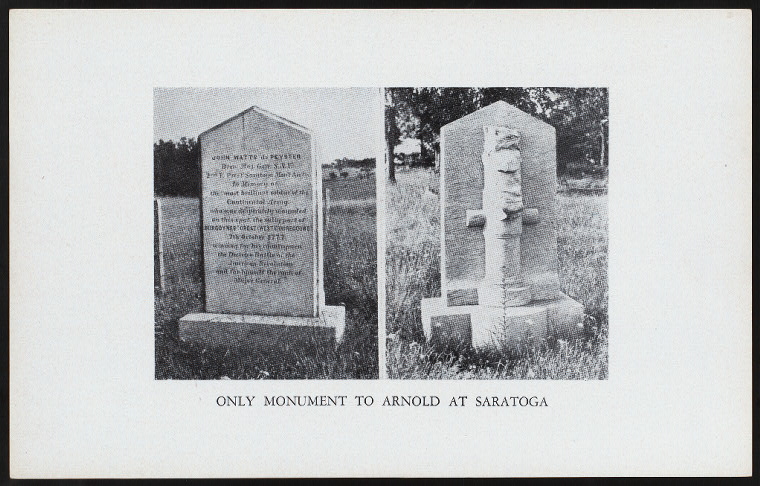

Three hours from the upstate New York village of Sleepy Hollow, in the woods of Schuylerville, there stands the statue of a leg. A boot, actually, a man’s riding boot, along with an epaulet and a cannon barrel pointing down, denoting the death of a General. It seems the loneliest place on earth out there in the woods, with nothing but a footpath worn into the forest floor to lead you there.

It was October 7, 1777, the last day of the Battle of Saratoga. General Horatio Gates was in overall command of American forces, a position which greatly exceeded his capabilities. Gates was cautious to the point of timidity, generally believing his men to be better off behind prepared fortifications, than taking the offensive.

Gates’ subordinate, General Benedict Arnold, could not have been more different. Arnold was imaginative and daring, a risk taker possessed of physical courage bordering on recklessness. The pair had been personal friends at one time. By this time the two were often at odds.

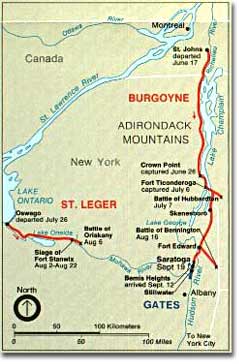

British General John “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne led a joint land and water invasion of 7,000 British and Hessian troops south along the New York side of Lake Champlain, down the Hudson River valley.

It had started out well for him with the bloodless capture of Fort Ticonderoga, but Burgoyne ran into a buzz saw outside of Bennington, Vermont, losing almost 1,000 men to General John Stark’s New Hampshire rebels and a militia unit headed by Ethan Allen, calling itself the “Green Mountain Boys”.

Burgoyne intended to continue south to Albany, linking up with forces under Sir William Howe and cutting the colonies in half. The 10,000 or so Colonial troops situated on the high ground near Saratoga, New York, were all that stood in his way.

American forces selected a site called Bemis Heights, about 10 miles south of Saratoga, spending a week constructing defensive works with the help of Polish engineer Thaddeus Kosciusko. It was a formidable position: mutually supporting cannon on overlapping ridges, with interlocking fields of fire. Burgoyne knew he had no choice but to stop and give battle at the American position, or be chopped to pieces trying to bypass it.

American forces selected a site called Bemis Heights, about 10 miles south of Saratoga, spending a week constructing defensive works with the help of Polish engineer Thaddeus Kosciusko. It was a formidable position: mutually supporting cannon on overlapping ridges, with interlocking fields of fire. Burgoyne knew he had no choice but to stop and give battle at the American position, or be chopped to pieces trying to bypass it.

The Battle of Freeman’s Farm, the first of two battles for Saratoga, occurred on September 19. Technically a Patriot defeat in that the British held the ground at the end of the day, it was a costly victory. English casualties were almost two to one. Worse, the British column was out at the end of a long and tenuous supply line, while fresh men and supplies continued to move into the American position.

Freeman’s Farm could have been a lot worse for the Patriot cause, but for Benedict Arnold’s anticipating British moves, and taking steps to block them in advance.

The personal animosity between Gates and Arnold boiled over in the days that followed. Gates’ report to Congress made no mention of Arnold’s contributions at Freeman’s Farm, though field commanders and the men involved with the day’s fighting unanimously crediting Arnold for the day’s successes. A shouting match between Gates and Arnold resulted in the latter being relieved of command, and replaced by General Benjamin Lincoln.

The second and decisive battle for Saratoga, the Battle of Bemis Heights, occurred on October 7, 1777.

The second and decisive battle for Saratoga, the Battle of Bemis Heights, occurred on October 7, 1777.

Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich Christoph Breymann’s Hessian grenadier regiment formed the right anchor of Burgoyne’s line, manning a wooden fortification some 250′ wide by 7′ high. It was a strategically important position, with nothing between itself and the regiment’s main camp to the rear.

Even though relieved of command, Benedict Arnold was on the field, directing the battle on the American right. As the Hessian position began to collapse, General Arnold left his troops facing Balcarre’s Redoubt on the right, riding between the fire of both armies and joining the final attack on the rear of the German post. Arnold was shot in the left leg during the final moments of the action, shattering the same leg that had barely healed after the same injury at the Battle of Quebec City, almost two years earlier.

It would have been better in the chest, he said, than to have received such a wound in that leg.

Burgoyne had no choice but to capitulate, surrendering his entire force on the 17th of October. It was a devastating defeat for the British cause, which finally brought France in on the American side. A colonial Army had gone toe to toe with the most powerful military on the planet, and was still standing.

A British officer described the battle: “The courage and obstinacy with which the Americans fought were the astonishment of everyone, and we now became fully convinced that they are not that contemptible enemy we had hitherto imagined them, incapable of standing a regular engagement, and that they would only fight behind strong and powerful works.”

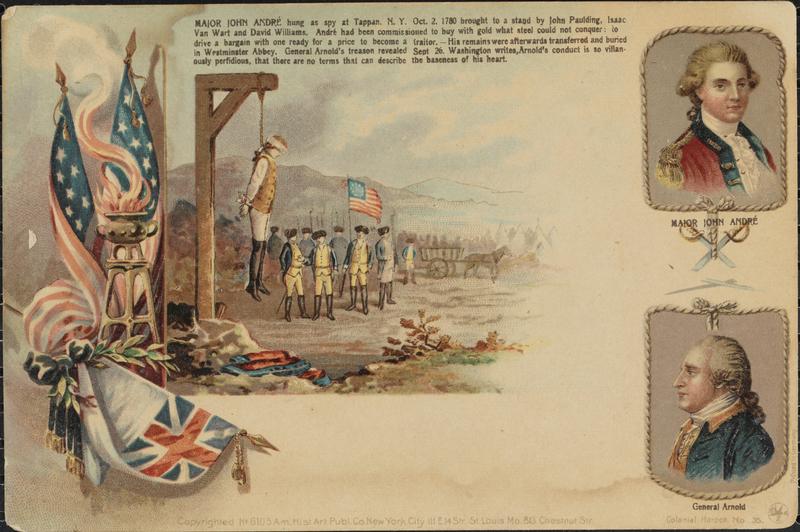

Three years later, Benedict Arnold betrayed the American fortifications at West Point to John André. The name of one of our top Revolution-era warriors, a General whom one of his own soldiers later described as “the very genius of war,” became that of Traitor.

One of Arnold’s contemporaries commented that, if the Patriots ever caught him they would hang him, and then they would bury his leg with full military honors.

So it is that there is a statue of a leg in the forest south of Saratoga, dedicated to a Hero of the Revolution who has no name. On the back of the monument are inscribed these words:

“In memory of

the most brilliant soldier of the

Continental Army

who was desperately wounded

on this spot the sally port of

BURGOYNES GREAT WESTERN REDOUBT

7th October, 1777

winning for his countrymen

the decisive battle of the

American Revolution

and for himself the rank of

Major General.”

Today, the Saratoga battlefield and the site of Burgoyne’s surrender are preserved as the Saratoga National Historical Park. On the grounds of the park stands an obelisk, containing four niches.

Today, the Saratoga battlefield and the site of Burgoyne’s surrender are preserved as the Saratoga National Historical Park. On the grounds of the park stands an obelisk, containing four niches.

Three of them hold statues of American heroes of the Battle. There is one for General Horatio Gates, one for General Philip John Schuyler and another for Colonel Daniel Morgan.

The fourth niche, where Benedict Arnold’s statue would have gone, remains empty, to this day.

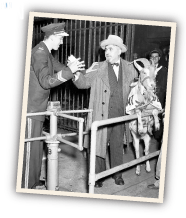

It was game four of the World Series between the Cubbies and the Detroit Tigers, October 6, 1945, with Chicago home at Wrigley Field. Billy Sianis, owner of the Billy Goat Tavern in Chicago, bought tickets for himself and his pet goat “Murphy”. Anyone who’s ever found himself in the company of a goat understands the problem. Right?

It was game four of the World Series between the Cubbies and the Detroit Tigers, October 6, 1945, with Chicago home at Wrigley Field. Billy Sianis, owner of the Billy Goat Tavern in Chicago, bought tickets for himself and his pet goat “Murphy”. Anyone who’s ever found himself in the company of a goat understands the problem. Right? Billy Sianis was right. The Cubs were up two games to one at the time, but they went on to lose the series. They’ve been losing ever since.

Billy Sianis was right. The Cubs were up two games to one at the time, but they went on to lose the series. They’ve been losing ever since. Alou slammed his glove down in anger and frustration. Pitcher Mark Prior glared at the stands, crying “fan interference”. The Marlins came back with 8 unanswered runs in the inning. Steve Bartman required a police escort to get out of the field alive.

Alou slammed his glove down in anger and frustration. Pitcher Mark Prior glared at the stands, crying “fan interference”. The Marlins came back with 8 unanswered runs in the inning. Steve Bartman required a police escort to get out of the field alive.

The mother of all droughts came to a halt on November 2 in a ten-inning cardiac arrest that had us all up Way past midnight, on a school night. I even watched that 17-minute rain delay, and I’m a Red Sox guy.

The mother of all droughts came to a halt on November 2 in a ten-inning cardiac arrest that had us all up Way past midnight, on a school night. I even watched that 17-minute rain delay, and I’m a Red Sox guy.

The family settled for a time in Hannover, West Germany, barely avoiding the communist noose as it closed around their former home in the East.

The family settled for a time in Hannover, West Germany, barely avoiding the communist noose as it closed around their former home in the East.

Steppenwolf gave us 22 albums. We all know them in one way or another. Yet, the lead singer’s escape from the horrors of the Iron Curtain, not once but twice, is all but unknown. That, as Paul Harvey used to say, is the Rest, of the Story.

Steppenwolf gave us 22 albums. We all know them in one way or another. Yet, the lead singer’s escape from the horrors of the Iron Curtain, not once but twice, is all but unknown. That, as Paul Harvey used to say, is the Rest, of the Story.

Major Whittlesey, Captain George McMurtry, and Captain Nelson Holderman, all received the Medal of Honor for their actions atop hill 198. Whittlesey was accorded the rare honor of being a pallbearer at the interment ceremony for the Unknown Soldier, but it seems his experience weighed heavily on him. Charles Whittlesey disappeared from a ship in 1921, in what is believed to have been a suicide.

Major Whittlesey, Captain George McMurtry, and Captain Nelson Holderman, all received the Medal of Honor for their actions atop hill 198. Whittlesey was accorded the rare honor of being a pallbearer at the interment ceremony for the Unknown Soldier, but it seems his experience weighed heavily on him. Charles Whittlesey disappeared from a ship in 1921, in what is believed to have been a suicide.

Once, the small dog was able to perform a task in minutes that otherwise would have taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire. The air field at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, was crucial to the Allied war effort, and the signal corps needed to run a telegraph wire across the field. A 70′ long, 8” pipe crossed underneath the air strip, half filled with dirt.

Once, the small dog was able to perform a task in minutes that otherwise would have taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire. The air field at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, was crucial to the Allied war effort, and the signal corps needed to run a telegraph wire across the field. A 70′ long, 8” pipe crossed underneath the air strip, half filled with dirt. Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and entertaining thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s considered to be the first therapy dog, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed.

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and entertaining thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s considered to be the first therapy dog, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed. Bill Wynne was 90 years old in 2012, when he was “flabbergasted” to be approached by Australian authorities. They explained that an Australian army nurse had purchased the dog from a Queen Street pet store, becoming separated in the jungles of New Guinea. 68 years later, the Australians had come to award his dog a medal.

Bill Wynne was 90 years old in 2012, when he was “flabbergasted” to be approached by Australian authorities. They explained that an Australian army nurse had purchased the dog from a Queen Street pet store, becoming separated in the jungles of New Guinea. 68 years later, the Australians had come to award his dog a medal.

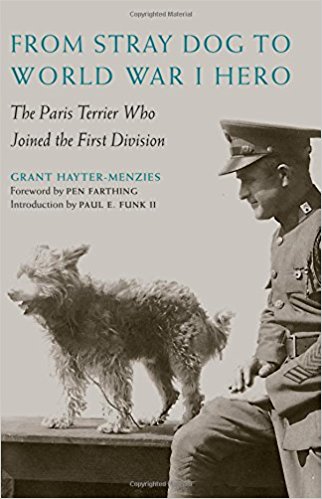

It was a small dog, possibly a Cairn Terrier mix. He looked like a pile of rags, and that’s what they called him. The dog had gotten Donovan out of a jam, now he would become the division mascot for real. Rags was now part of the US 1st Infantry Division, the Big Red One.

It was a small dog, possibly a Cairn Terrier mix. He looked like a pile of rags, and that’s what they called him. The dog had gotten Donovan out of a jam, now he would become the division mascot for real. Rags was now part of the US 1st Infantry Division, the Big Red One.

Other tree ancestors include the Water Oak next to the Brown Chapel African Methodist Church in Selma, where Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his “We Shall Overcome” speech, before setting out on the 50-mile march to Montgomery. The George Washington American Holly was grown from seeds gathered at Mount Vernon. Helen Keller climbed the 100-year-old Water Oak, as a child. The Overcup Oak descends from a tree which shaded the birthplace of the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln.

Other tree ancestors include the Water Oak next to the Brown Chapel African Methodist Church in Selma, where Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his “We Shall Overcome” speech, before setting out on the 50-mile march to Montgomery. The George Washington American Holly was grown from seeds gathered at Mount Vernon. Helen Keller climbed the 100-year-old Water Oak, as a child. The Overcup Oak descends from a tree which shaded the birthplace of the 16th President of the United States, Abraham Lincoln.

Pitchers Eddie Cicotte and Claude “Lefty” Williams, along with outfielder Oscar “Hap” Felsch, and shortstop Charles “Swede” Risberg were all principally involved with fixing the series. Third baseman George “Buck” Weaver was at a meeting where the fix was discussed, but decided not to participate. Weaver handed in some of his best statistics of the year during the Series.

Pitchers Eddie Cicotte and Claude “Lefty” Williams, along with outfielder Oscar “Hap” Felsch, and shortstop Charles “Swede” Risberg were all principally involved with fixing the series. Third baseman George “Buck” Weaver was at a meeting where the fix was discussed, but decided not to participate. Weaver handed in some of his best statistics of the year during the Series. Rumors were flying when the series started on October 2. So much money was on Cincinnati that the odds were flat. Gamblers complained that nothing was left on the table. Williams lost his three games in the best-out-of nine series, which I believe stands as a World Series record to this day. Cicotte became angry, thinking that gamblers were trying to renege, and he bore down, the White Sox winning game 7.

Rumors were flying when the series started on October 2. So much money was on Cincinnati that the odds were flat. Gamblers complained that nothing was left on the table. Williams lost his three games in the best-out-of nine series, which I believe stands as a World Series record to this day. Cicotte became angry, thinking that gamblers were trying to renege, and he bore down, the White Sox winning game 7. Ironically, the 1919 scandal would lead to a White Sox crash in the 1921 season, beginning the “Curse of the Black Sox”. It was a World Series championship drought that lasted 88 years, ending only in 2005, with a sweep of the Houston Astros. Exactly one year after the Boston Red Sox ended their own 86-year drought, the “Curse of the Bambino”.

Ironically, the 1919 scandal would lead to a White Sox crash in the 1921 season, beginning the “Curse of the Black Sox”. It was a World Series championship drought that lasted 88 years, ending only in 2005, with a sweep of the Houston Astros. Exactly one year after the Boston Red Sox ended their own 86-year drought, the “Curse of the Bambino”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.