Throughout the history of armed conflict, men who have endured combat together have formed a special bond. Prior to the David vs. Goliath battle at Agincourt, Henry V spoke of “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers“. The men who fought the “War to end all wars” spoke not of God and Country, but of the man to his left and right. What then does it look like, when the man you’re fighting for is literally your own brother?

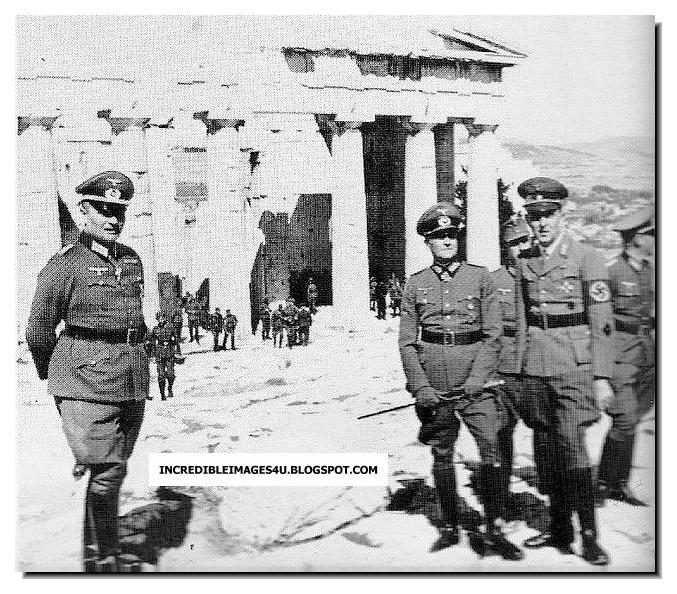

Hellenic forces enjoyed early success when fascist Italy invaded Greece on October 28, 1940, the Greek army driving the intruder into neighboring Albania in the first Allied land victory of the second World War.

Until the intervention of Nazi Germany and her Bulgarian ally.

British commonwealth troops moved from Libya on orders from Winston Churchill proved too little, too late. The Greek capital at Athens fell on April, 27. Greece suffered axis occupation for the rest of the war, with devastating results. Some 80% of Greek industry was destroyed along with 90 percent of ports, roads, bridges and other infrastructure. 40,000 civilians died of starvation, in Athens alone. Tens of thousands more died in Nazi reprisals, or at the hands of Nazi collaborators.

Fearful of losing the strategically important island of Crete, Prime minister Winston Churchill sent a telegram to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff General Sir John Dill: “To lose Crete because we had not sufficient bulk of forces there would be a crime.”

By the end of April, the Royal Navy evacuated 57,000 troops to Crete, largest of the islands comprising the modern Greek state. They’d been sent to bolster the Cretan garrison until the arrival of fresh forces, but this was a spent force. Most had lost heavy equipment in the hasty evacuation. Many were unarmed, altogether.

Occupied at this time with operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s surprise invasion of his erstwhile Soviet ally, German Army command had little desire to go after Crete. Eager to redeem themselves following the failure to destroy an all-but prostrate adversary during the Battle of Britain, Luftwaffe High Command was a different story.

Hitler recognized the strategic importance of Crete, both to the air war in the eastern Mediterranean and for the protection of the Axis southern flank.

By the time of the German invasion, Allied forces were reduced to 42,000 on Crete of which only 15,000, were combat ready. New Zealand Army Major-General Bernard Freyberg in command of these troops, requested evacuation of 10,000 who had “little or no employment other than getting into trouble with the civil population“.

Once again it was too little, to late. The first mainly airborne invasion in military history and the only such German operation of WW2 began on May 20, 1941.

The Luftwaffe sent 280 long-range bombers, 150 dive-bombers, 180 fighters and 40 reconnaissance aircraft into the attack, along with 530 transport aircraft and 100 gliders.

The allied garrison was soon outnumbered and fighting for their lives. Recognizing that the battle was lost, leadership in London instructed Freyberg to abandon the island, on May 27.

The “Victoria Cross” is the highest accolade in the British system of military honors, equivalent to the American Medal of Honor. Sergeant Clive Hulme of the New Zealand 2nd Division was part of that fighting withdrawal. He was 30 years old at the time of the battle for Crete where his actions, earned him the Victoria Cross. Let Sergeant Hulme’s citation, tell his story:

“On ground overlooking Malene Aerodrome on 20th and 21st May [Sergeant Hulme] personally led parties of his men from the area held by the forward position and destroyed enemy organised parties who had established themselves out in front of our position, from which they brought heavy rifle, machine-gun and mortar fire to bear on our defensive posts. Numerous snipers in the area were dealt with by Serjeant Hulme personally; 130 dead were counted here. On 22nd, 23rd and 24th May, Serjeant Hulme was continuously going out alone or with one or two men and destroying enemy snipers. On 25th May, when Serjeant Hulme had rejoined his Battalion, this unit counter-attacked Galatas Village. The attack was partially held up by a large party of the enemy holding the school, from which they were inflicting heavy casualties on our troops. Serjeant Hulme went forward alone, threw grenades into the school and so disorganised the defence, that the counter-attack was able to proceed successfully.”

On this day in 1941, Sergeant Clive Hulme learned of the death of his brother Harold, also fighting in the battle for Crete. The life expectancy for German snipers was about to become noticeably shorter. Again, from Hulme’s VC citation:

On Tuesday, 27th May, when our troops were holding a defensive line in Suda Bay during the final retirement, five enemy snipers had worked into position on the hillside overlooking the flank of the Battalion line. Serjeant Hulme volunteered to deal with the situation, and stalked and killed the snipers in turn. He continued similar work successfully through the day. On 28th May at Stylos, when an enemy heavy mortar was severely bombing a very important ridge held by the Battalion rearguard troops, inflicting severe casualties, Serjeant Hulme, on his own initiative, penetrated the enemy lines, killed the mortar crew of four…From the enemy mortar position he then worked to the left flank and killed three snipers who were causing concern to the rearguard. This made his score of enemy snipers 33 stalked and shot. Shortly afterwards Serjeant Hulme was severely wounded in the shoulder while stalking another sniper. When ordered to the rear, in spite of his wound, he directed traffic under fire and organised stragglers of various units into section groups.”

The man took out 33 German snipers by himself in 8 days and still assisted in the withdrawal, after being shot badly enough to put him out for the rest of the war.

Some guys are not to be trifled with.

Circus-like performing dwarves were common enough at this time but the Ovitz siblings were different. These were talented musicians playing quarter-sized instruments, performing a variety show throughout the 1930s and early ’40s as the “Lilliput Troupe”. The family performed throughout Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, with their normal height siblings serving as “roadies”. And then came the day. The whole lot of them were swept up by the Nazis and deported to the concentration camp and extermination center, at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Circus-like performing dwarves were common enough at this time but the Ovitz siblings were different. These were talented musicians playing quarter-sized instruments, performing a variety show throughout the 1930s and early ’40s as the “Lilliput Troupe”. The family performed throughout Romania, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, with their normal height siblings serving as “roadies”. And then came the day. The whole lot of them were swept up by the Nazis and deported to the concentration camp and extermination center, at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

On one occasion, the Angel of Death told the family they were “going to a beautiful place”. Terrified, the siblings were given makeup, and told to dress themselves. Brought to a nearby theater and placed onstage, the family must have thought they’d be asked to perform. Instead, Mengele ordered them to undress, leaving all seven naked before a room full of SS men. Mengele then gave a speech and invited the audience onstage, to poke and prod at the humiliated family.

On one occasion, the Angel of Death told the family they were “going to a beautiful place”. Terrified, the siblings were given makeup, and told to dress themselves. Brought to a nearby theater and placed onstage, the family must have thought they’d be asked to perform. Instead, Mengele ordered them to undress, leaving all seven naked before a room full of SS men. Mengele then gave a speech and invited the audience onstage, to poke and prod at the humiliated family.

Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. In 1949, the family emigrated to Israel and resumed their musical tour, performing until the group retired in 1955.

Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. In 1949, the family emigrated to Israel and resumed their musical tour, performing until the group retired in 1955.

March elections failed to produce a Nazi party majority. For the time being, Herr Hitler was forced to rely on his coalition partner the German National People’s Party (DNVP), to hold a majority in the new Reichstag.

March elections failed to produce a Nazi party majority. For the time being, Herr Hitler was forced to rely on his coalition partner the German National People’s Party (DNVP), to hold a majority in the new Reichstag. Nazi propaganda was relentless. Hitler himself had written back in 1924, that propaganda’s “task is not to make an objective study of the truth, in so far as it favors the enemy, and then set it before the masses with academic fairness; its task is to serve our own right, always and unflinchingly.”

Nazi propaganda was relentless. Hitler himself had written back in 1924, that propaganda’s “task is not to make an objective study of the truth, in so far as it favors the enemy, and then set it before the masses with academic fairness; its task is to serve our own right, always and unflinchingly.” Jacob and Pauline Levinsons came to Berlin in 1928, a few years before Hitler came to power. Both Latvian Jews, the couple gave birth to a beautiful baby girl on this day in 1934. Later that year, the proud parents brought wide-eyed, curly haired, chubby little Hessy to photographer Hans Ballin of Berlin.

Jacob and Pauline Levinsons came to Berlin in 1928, a few years before Hitler came to power. Both Latvian Jews, the couple gave birth to a beautiful baby girl on this day in 1934. Later that year, the proud parents brought wide-eyed, curly haired, chubby little Hessy to photographer Hans Ballin of Berlin. And that’s where the story ends, except, no. Unbeknownst to the Levinsons, the photographer submitted the portrait in a contest, a search for the perfect Aryan child.

And that’s where the story ends, except, no. Unbeknownst to the Levinsons, the photographer submitted the portrait in a contest, a search for the perfect Aryan child.

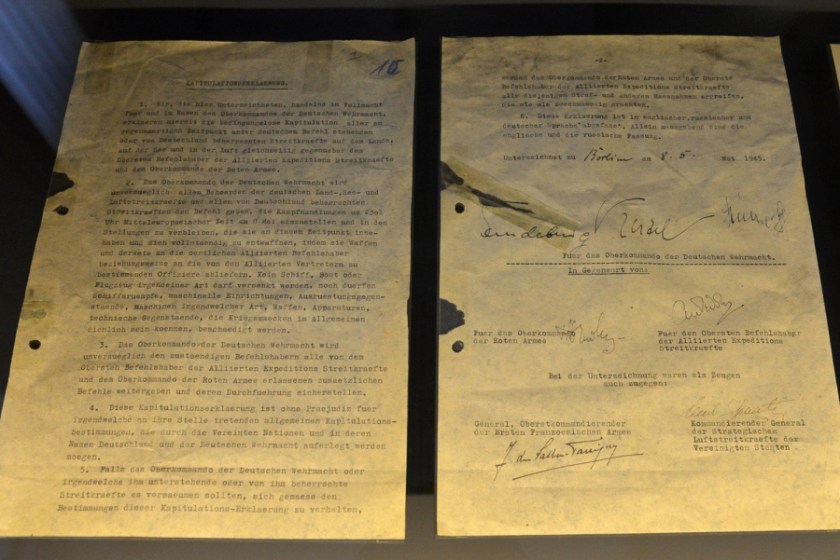

The German government announced the end of hostilities right away to its own people, but most of the Allied governments, remained silent. It was nearly midnight the following day when Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel signed a second instrument of surrender, in the Berlin headquarters of Soviet General Georgy Zhukov.

The German government announced the end of hostilities right away to its own people, but most of the Allied governments, remained silent. It was nearly midnight the following day when Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel signed a second instrument of surrender, in the Berlin headquarters of Soviet General Georgy Zhukov. And still, the world waited.

And still, the world waited. President Truman’s speech begins: “This is a solemn but a glorious hour. I only wish that Franklin D. Roosevelt had lived to witness this day. General Eisenhower informs me that the forces of Germany have surrendered to the United Nations. The flags of freedom fly over all Europe. For this victory, we join in offering our thanks to the Providence which has guided and sustained us through the dark days of adversity”.

President Truman’s speech begins: “This is a solemn but a glorious hour. I only wish that Franklin D. Roosevelt had lived to witness this day. General Eisenhower informs me that the forces of Germany have surrendered to the United Nations. The flags of freedom fly over all Europe. For this victory, we join in offering our thanks to the Providence which has guided and sustained us through the dark days of adversity”. Nearly every extermination camp, death march, ghetto and pogrom now remembered as the Holocaust, occurred on the Eastern Front.

Nearly every extermination camp, death march, ghetto and pogrom now remembered as the Holocaust, occurred on the Eastern Front.

The United States was grossly unprepared to fight a World War in 1942. The latest iteration of “War Plan Orange” (WPO-3) called for delaying tactics in the event of war with Japan, buying time to gather US Naval assets to sail for the Philippines. The problem was, there was no fleet to gather. The flower of American pacific power in the pacific, lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Allied war planners turned their attention to defeating Adolf Hitler.

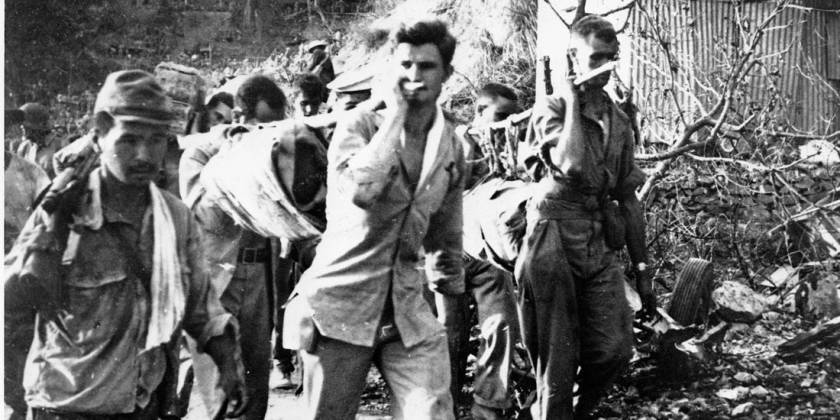

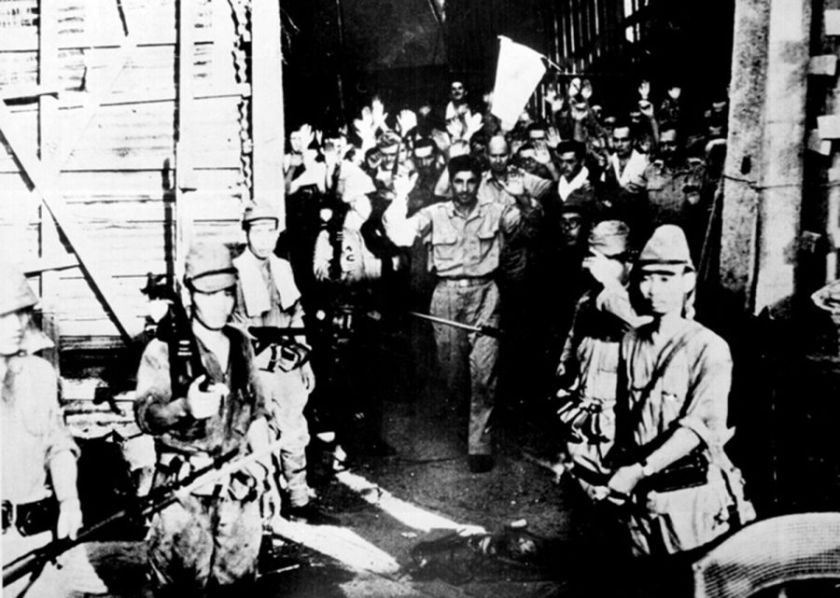

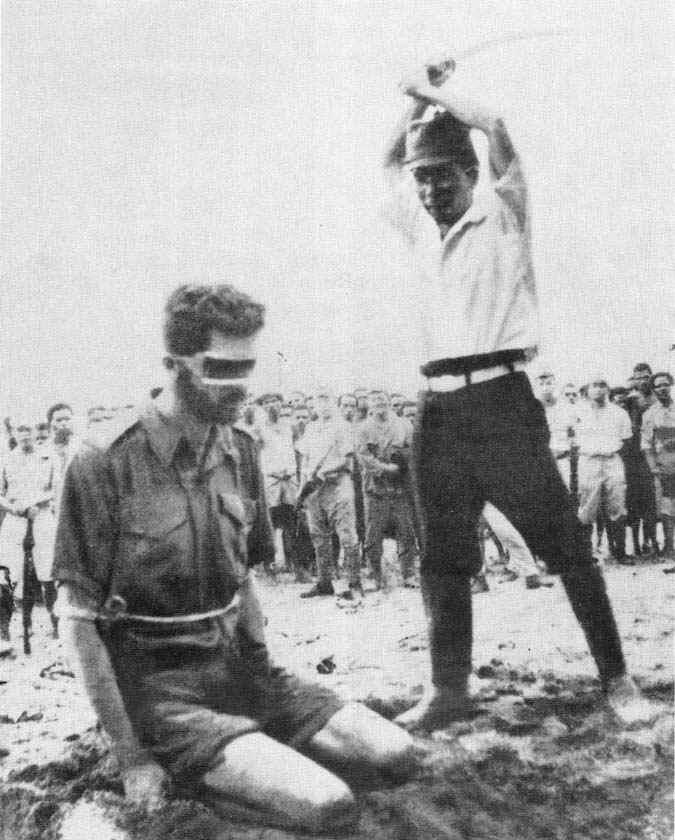

The United States was grossly unprepared to fight a World War in 1942. The latest iteration of “War Plan Orange” (WPO-3) called for delaying tactics in the event of war with Japan, buying time to gather US Naval assets to sail for the Philippines. The problem was, there was no fleet to gather. The flower of American pacific power in the pacific, lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Allied war planners turned their attention to defeating Adolf Hitler. Japanese guards were sadistic. They would beat marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Tormented by a thirst few among us can so much as imagine, men were made to stand for hours under a relentless sun, standing by a stream from which none were permitted to drink. The man who broke ranks and dove for the water was clubbed or bayoneted to death, on the spot. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive, others buried alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, w

Japanese guards were sadistic. They would beat marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Tormented by a thirst few among us can so much as imagine, men were made to stand for hours under a relentless sun, standing by a stream from which none were permitted to drink. The man who broke ranks and dove for the water was clubbed or bayoneted to death, on the spot. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive, others buried alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, w United States Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Austin Shofner came ashore back in November, with the 4th Marines. Shofner and his fellow leathernecks engaged the Japanese as early as December 12 and received their first taste of aerial bombardment, on December 29. Promoted to Captain and placed in command of Headquarters Company, Shofner received two Silver Stars by April 15 in near-constant defense against aerial attack.

United States Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Austin Shofner came ashore back in November, with the 4th Marines. Shofner and his fellow leathernecks engaged the Japanese as early as December 12 and received their first taste of aerial bombardment, on December 29. Promoted to Captain and placed in command of Headquarters Company, Shofner received two Silver Stars by April 15 in near-constant defense against aerial attack.

Nearly 150,000 Allied soldiers were taken captive by the Japanese Empire, during World War 2. Clad in unspeakably filthy rags they were fed a mere 600 calories per day of fouled rice, supplemented only by the occasional insect or bird or rodent unlucky enough to fall into desperate hands. Disease such as malaria was all but universal as gross malnutrition led to loss of vision and unrelenting nerve pain. Dysentery, a hideously infectious disease of the large intestine reduced grown men to animated skeletons. Mere scratches resulted in grotesque tropical ulcers up to a foot in length exposing living bone and rotting flesh to swarms of ravenous insects.

Nearly 150,000 Allied soldiers were taken captive by the Japanese Empire, during World War 2. Clad in unspeakably filthy rags they were fed a mere 600 calories per day of fouled rice, supplemented only by the occasional insect or bird or rodent unlucky enough to fall into desperate hands. Disease such as malaria was all but universal as gross malnutrition led to loss of vision and unrelenting nerve pain. Dysentery, a hideously infectious disease of the large intestine reduced grown men to animated skeletons. Mere scratches resulted in grotesque tropical ulcers up to a foot in length exposing living bone and rotting flesh to swarms of ravenous insects. Given such cruel conditions it’s a wonder anyone escaped at all but it did happen. Once.

Given such cruel conditions it’s a wonder anyone escaped at all but it did happen. Once.

Now-Colonel Shofner volunteered to return to the Pacific where his experience helped with the rescue of 500 prisoners of the infamous POW camp at Cabanatuan on January 30, 1945.

Now-Colonel Shofner volunteered to return to the Pacific where his experience helped with the rescue of 500 prisoners of the infamous POW camp at Cabanatuan on January 30, 1945.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC.

Radios of the age didn’t work across the Rockies, and the mail was erratic. The only passenger service available was run by the Yukon Southern airline, a run which locals called the “Yukon Seldom”. For construction battalions at Dawson Creek, Delta Junction and Whitehorse, it was faster to talk to each other through military officials in Washington, DC. Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food.

Tent pegs were useless in the permafrost, while the body heat of sleeping soldiers meant waking up in mud. Partially thawed lakes meant that supply planes could use neither pontoon nor ski, as Black flies swarmed the troops by day. Hungry bears raided camps at night, looking for food. That October, Refines Sims Jr. of Philadelphia, with the all-black 97th Engineers, was driving a bulldozer 20 miles east of the Alaska-Yukon line when the trees in front of him toppled to the ground. Sims slammed his machine into reverse as a second bulldozer came into view, driven by Kennedy, Texas Private Alfred Jalufka. North had met south, and the two men jumped off their machines, grinning. Their triumphant handshake was photographed by a fellow soldier and published in newspapers across the country, becoming an unintended first step toward desegregating the US military.

That October, Refines Sims Jr. of Philadelphia, with the all-black 97th Engineers, was driving a bulldozer 20 miles east of the Alaska-Yukon line when the trees in front of him toppled to the ground. Sims slammed his machine into reverse as a second bulldozer came into view, driven by Kennedy, Texas Private Alfred Jalufka. North had met south, and the two men jumped off their machines, grinning. Their triumphant handshake was photographed by a fellow soldier and published in newspapers across the country, becoming an unintended first step toward desegregating the US military.

German submarine wolf packs had already sunk several ships in these waters. Late on the night of February 2, one of the Cutters flashed flashed the light signal “we’re being followed”.

German submarine wolf packs had already sunk several ships in these waters. Late on the night of February 2, one of the Cutters flashed flashed the light signal “we’re being followed”. Those who could escape scrambled onto the deck, injured, disoriented, many still in their underwear as they emerged into the cold and darkness.

Those who could escape scrambled onto the deck, injured, disoriented, many still in their underwear as they emerged into the cold and darkness. Dorchester was listing hard to starboard and taking on water fast, with only 20 minutes to live. Port side lifeboats were inoperable due to the ship’s angle. Men jumped across the void into those on the starboard side, overcrowding some to the point of capsize. Only two of fourteen lifeboats launched successfully.

Dorchester was listing hard to starboard and taking on water fast, with only 20 minutes to live. Port side lifeboats were inoperable due to the ship’s angle. Men jumped across the void into those on the starboard side, overcrowding some to the point of capsize. Only two of fourteen lifeboats launched successfully. Rushing back to the scene, coast guard cutters found themselves in a sea of bobbing red lights, the water-activated emergency strobe lights of individual life jackets. Most marked the location of corpses. Of the 904 on board, the Coast Guard plucked 230 from the water, alive.

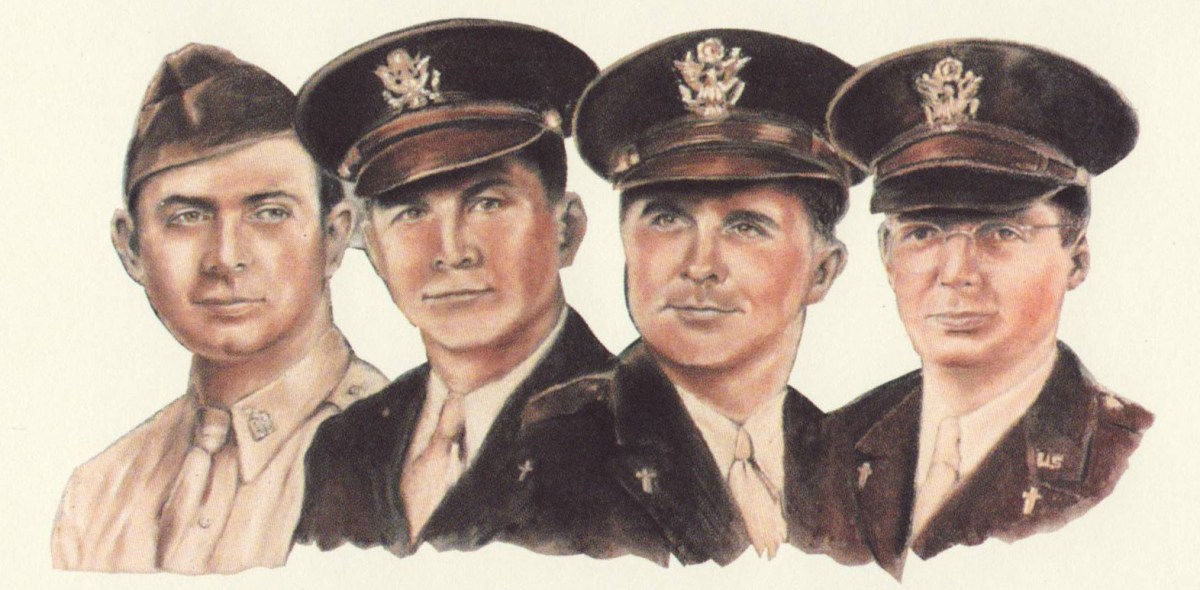

Rushing back to the scene, coast guard cutters found themselves in a sea of bobbing red lights, the water-activated emergency strobe lights of individual life jackets. Most marked the location of corpses. Of the 904 on board, the Coast Guard plucked 230 from the water, alive. John 15:13 teaches us, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”. Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew when he gave away his only hope for survival, Father Washington did not ask for a Catholic. Neither minister Fox nor Poling asked for a Protestant. Each gave his life jacket to the nearest man.

John 15:13 teaches us, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”. Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew when he gave away his only hope for survival, Father Washington did not ask for a Catholic. Neither minister Fox nor Poling asked for a Protestant. Each gave his life jacket to the nearest man.

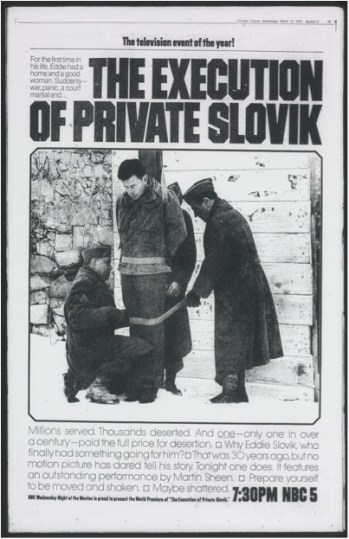

There the couple may have ridden out WWII, but the war was consuming manpower at a rate unprecedented in history. Shortly after the couple’s first anniversary, Slovik was re-classified 1A, fit for service, and drafted into the Army. Arriving in France on August 20, 1944, he was part of a 12-man replacement detachment, assigned to Company G of the 109th Infantry Regiment, US 28th Infantry Division.

There the couple may have ridden out WWII, but the war was consuming manpower at a rate unprecedented in history. Shortly after the couple’s first anniversary, Slovik was re-classified 1A, fit for service, and drafted into the Army. Arriving in France on August 20, 1944, he was part of a 12-man replacement detachment, assigned to Company G of the 109th Infantry Regiment, US 28th Infantry Division. of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”. On December 9, Slovik wrote to Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. Desertion was a systemic problem at this time. Particularly after the surprise German offensive coming out of the frozen Ardennes Forest on December 16, an action that went into history as the Battle of the Bulge. Eisenhower approved the execution order on December 23, believing it to be the only way to discourage further desertions.

On December 9, Slovik wrote to Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, pleading for clemency. Desertion was a systemic problem at this time. Particularly after the surprise German offensive coming out of the frozen Ardennes Forest on December 16, an action that went into history as the Battle of the Bulge. Eisenhower approved the execution order on December 23, believing it to be the only way to discourage further desertions.

Nick Gozik of Pittsburg passed away in 2015, at the age of 95. He was there in 1945, a fellow soldier called to witness the execution. “Justice or legal murder”, he said, “I don’t know, but I want you to know I think he was the bravest man in that courtyard that day…All I could see was a young soldier, blond-haired, walking as straight as a soldier ever walked. I thought he was the bravest soldier I ever saw.”

Nick Gozik of Pittsburg passed away in 2015, at the age of 95. He was there in 1945, a fellow soldier called to witness the execution. “Justice or legal murder”, he said, “I don’t know, but I want you to know I think he was the bravest man in that courtyard that day…All I could see was a young soldier, blond-haired, walking as straight as a soldier ever walked. I thought he was the bravest soldier I ever saw.”

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London Mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. Only a year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London Mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. Only a year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

This was no mindless panic. Zeppelin raids had killed 1,500 civilians in London alone during the ‘Great War’. Since then, governments had become infinitely better at killing each other’s citizens.

This was no mindless panic. Zeppelin raids had killed 1,500 civilians in London alone during the ‘Great War’. Since then, governments had become infinitely better at killing each other’s citizens. All things considered, the evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’

All things considered, the evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’ In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.”

In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.” Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians.

Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians. “Operation Steinbock”, the Luftwaffe’s last large-scale strategic bombing campaign of the war against southern England, was carried out three years later. On this day in 1944, 285 German bombers attacked London in what the Brits called, a “Baby Blitz”.

“Operation Steinbock”, the Luftwaffe’s last large-scale strategic bombing campaign of the war against southern England, was carried out three years later. On this day in 1944, 285 German bombers attacked London in what the Brits called, a “Baby Blitz”. Late in the war, the subsonic “Doodle Bug” or V1 “flying bomb” was replaced by the terrifying supersonic

Late in the war, the subsonic “Doodle Bug” or V1 “flying bomb” was replaced by the terrifying supersonic  In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

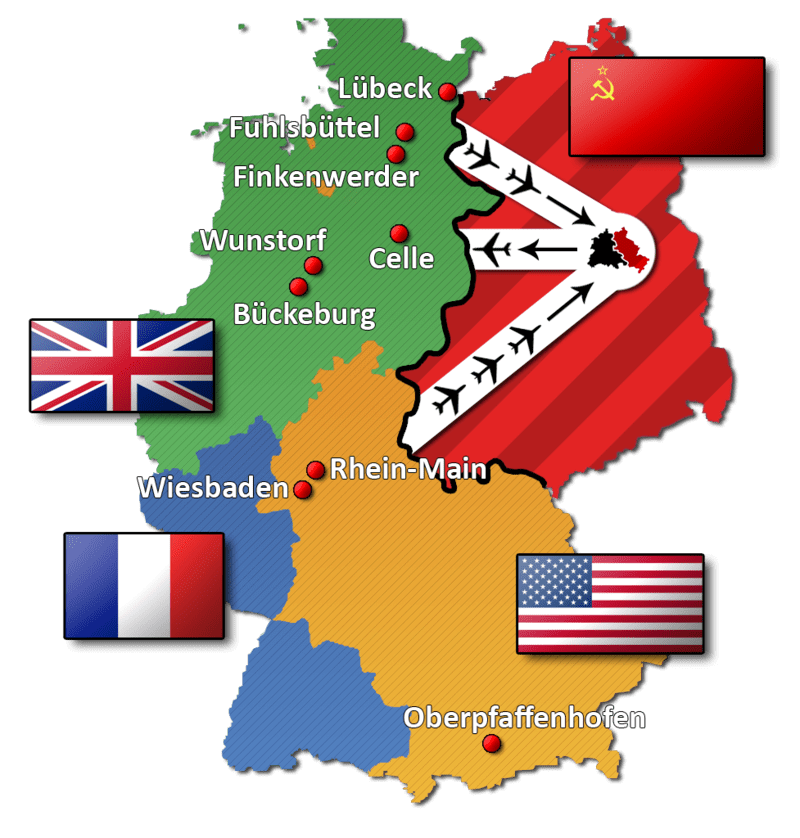

During the war, ideological fault lines were suppressed in the drive to destroy the Nazi war machine. Such differences were quick to reassert themselves in the wake of German defeat. In Soviet-occupied east Germany, factories and equipment were disassembled and transported to the Soviet Union, along with technicians, managers and skilled personnel.

During the war, ideological fault lines were suppressed in the drive to destroy the Nazi war machine. Such differences were quick to reassert themselves in the wake of German defeat. In Soviet-occupied east Germany, factories and equipment were disassembled and transported to the Soviet Union, along with technicians, managers and skilled personnel. West Berlin, a city utterly destroyed by war, was home to some 2.3 million at that time, roughly three times the city of Boston.

West Berlin, a city utterly destroyed by war, was home to some 2.3 million at that time, roughly three times the city of Boston. With that many lives at stake, allied authorities calculated a daily ration of only 1,990 calories would require 646 tons of flour and wheat, 125 tons of cereal, 64 tons of fat, 109 tons of meat and fish, 180 tons of dehydrated potatoes, 180 tons of sugar, 11 tons of coffee, 19 tons of powdered milk, 5 tons of whole milk for the children, 3 tons of fresh yeast for baking, 144 tons of dehydrated vegetables, 38 tons of salt and 10 tons of cheese.

With that many lives at stake, allied authorities calculated a daily ration of only 1,990 calories would require 646 tons of flour and wheat, 125 tons of cereal, 64 tons of fat, 109 tons of meat and fish, 180 tons of dehydrated potatoes, 180 tons of sugar, 11 tons of coffee, 19 tons of powdered milk, 5 tons of whole milk for the children, 3 tons of fresh yeast for baking, 144 tons of dehydrated vegetables, 38 tons of salt and 10 tons of cheese. What followed is known to history, as the

What followed is known to history, as the  US Army Air Force Colonel Gail “Hal” Halvorsen was one of those pilots, flying C-47s and C-54 aircraft deep inside of Soviet controlled territory. On his days off, Halvorsen liked to go sightseeing, often bringing a small movie camera.

US Army Air Force Colonel Gail “Hal” Halvorsen was one of those pilots, flying C-47s and C-54 aircraft deep inside of Soviet controlled territory. On his days off, Halvorsen liked to go sightseeing, often bringing a small movie camera. Newspapers got wind of what was going on. Halvorsen thought he’d be in trouble, but no. Lieutenant General William Henry Tunner liked the idea. A lot. “Operation Little Vittles” became official, on September 22.

Newspapers got wind of what was going on. Halvorsen thought he’d be in trouble, but no. Lieutenant General William Henry Tunner liked the idea. A lot. “Operation Little Vittles” became official, on September 22.

You must be logged in to post a comment.