Following the Mexican War of Independence with Spain, (1810 – 1821), Texas became a part of Mexico. In 1831, Mexican authorities gave the settlers of Gonzales a small swivel cannon, a defense against the raids of the Comanche. The political situation deteriorated in the following years. By 1835, several Mexican states were in open revolt. That September, commander of “Centralist” (Mexican) troops in Texas Colonel Domingo de Ugartechea, came to take it back.

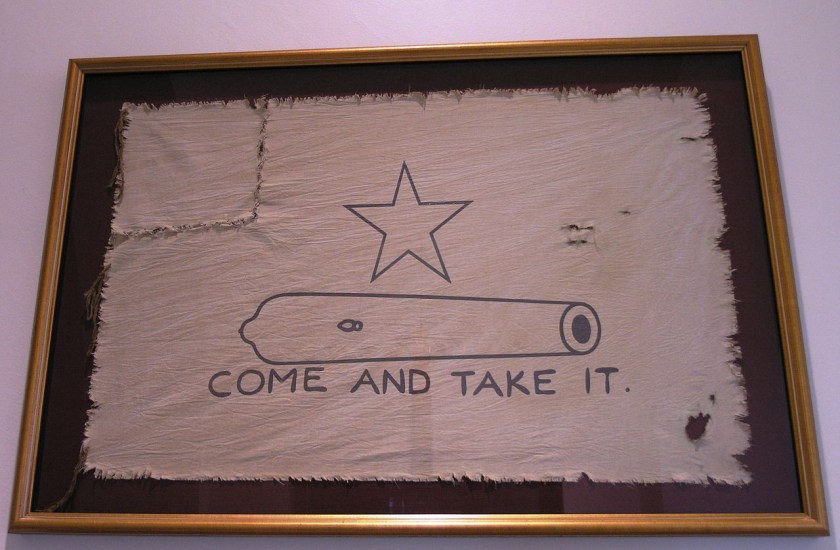

Dissatisfied with the increasingly dictatorial policies of President and General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, the colonists had no intention of handing over that cannon. One excuse was given after another to keep the Mexican dragoons out of Gonzalez, while secret pleas for help went out to surrounding communities. Within two days, 140 “Texians” had gathered in Gonzalez, fashioning a flag that echoed some 2,315 years through history, King Leonidas’ defiant response to the Persian tyrant, Xerxes: “Come and Take it.”

Militarily, the skirmish of October 2 had little significance, much the same as the early battles in the Massachusetts colony, some sixty years earlier. Politically, the “Lexington of Texas” marked a break between Texian settlers, and the Mexican government.

Settlers continued to gather, electing the well-respected local and former legislator of the Missouri territory Stephen F. Austin, as their leader. Santa Anna sent his brother-in-law, General Martin Perfecto de Cos to reinforce the settlement of San Antonio de Béxar, near the modern city of San Antonio. On the 13th, Austin led his Federalist army of Texians and their Tejano allies to Béxar, to confront the garrison. Austin’s forces captured the town that December, following a prolonged siege. It was only a matter of time before Santa Anna himself came to take it back.

Two forts – more like lonely outposts – blocked the only approaches from the Mexican interior into Texas: Presidio La Bahía (Nuestra Señora de Loreto Presidio) at Goliad and the Alamo at San Antonio de Béxar. That December, a group of volunteers led by George Collinsworth and Benjamin Milam overwhelmed the Mexican garrison at the Alamo, and captured the fort The Mexican President arrived on February 23 at the head of an army of 3,000, demanding its surrender. Lieutenant Colonel William Barret “Buck” Travis, responded with a cannon ball.

Knowing that his small force couldn’t hold for long against such an army, Travis sent out a series of pleas for help and reinforcement, writing “If my countrymen do not rally to my relief, I am determined to perish in the defense of this place, and my bones shall reproach my country for her neglect.” 32 troops attached to Lt. George Kimbell’s Gonzales ranging company made their way through the enemy cordon and into the Alamo on March 1. There would be no more.

Estimates of the Alamo garrison have ranged between 189 and 257 at this stage, but current sources indicate that defenders never numbered more than 200.

Estimates of the Alamo garrison have ranged between 189 and 257 at this stage, but current sources indicate that defenders never numbered more than 200.

On March 2, 1836, the interim government of Texas signed the Texas Declaration of Independence. The final assault on the Alamo began at 5:00am, four days later. 1,800 troops attacked from four directions. 600 to 1,600 were killed from concentrated artillery fire and close combat, but the numbers were overwhelming. Hand to hand fighting moved to the barracks after the walls were breached, and ended in the chapel.

As many as seven defenders still lived when it was over, many believe that former Congressman Davy Crockett was among them. Santa Anna ordered them summarily executed. By 8:00am there were no survivors, except for a handful of noncombatant women, children, and slaves, slowly emerging from the smoking ruins. These were provided with blankets and two dollars apiece, and given safe passage through Mexican lines with the warning: a similar fate awaited any Texan who continued in their revolt.

Three weeks later following the Battle of Coleto, 350 Texian prisoners were murdered by the Mexican army under direct orders from Santa Anna, an event remembered as the Goliad massacre.

The ranks of Sam Houston’s unit swelled with volunteers, as Houston’s army retreated eastward, along with the provisional government and hordes of civilians. Houston’s green and inexperienced force of 1,400, were now all that stood on the side of Texan independence.

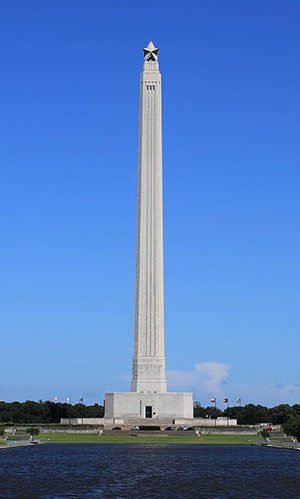

On April 21, a force of some 900 Texans shouting “Remember the Alamo!” & “Remember Goliad!” and led by Sam Houston defeated Santa Anna’s force of some 1,300 at San Jacinto, near modern day Houston. In “one of the most one-sided victories in history” 650 Mexican soldiers were killed in eighteen minutes and another 300 captured, compared with 11 Texians dead and another 30 wounded, including Houston itself. Mexican troops occupying San Antonio were ordered to withdraw, by May.

Intermittent conflicts continued into the 1840s between Texas and Mexico, but the outcome was never again placed in doubt. Texas became the 28th state of the United States on December 29, 1845.

As for Santa Anna, he went on to lose a leg to a cannon ball two years later, fighting the French at the Battle of Veracruz. Following amputation, the leg spent four years buried at Santa Anna’s hacienda, Manga de Clavo. When Santa Anna resumed the presidency in late 1841, he had the leg dug up and placed in a crystal vase, brought amidst a full military dress parade to Mexico City and escorted by the Presidential bodyguard, the army, and cadets from the military academy. This guy was nothing if not a self-promoter.

The leg was reburied in an elaborate ceremony in 1842, including cannon salvos, speeches, and poetry read in the General’s honor. The state funeral for Santa Anna’s leg was attended by his entire cabinet, the diplomatic corps, and the Congress.

Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna served 11 non-consecutive terms as Mexican President, spending most of his later years in exile in Jamaica, Cuba, the United States, Colombia, and St. Thomas. In 1869, the 74-year-old former President was living in Staten Island, trying to raise money for an army to return and take over Mexico City. Santa Anna is credited with bringing the first shipments of chicle to America, a gum-like substance made from the tree species, Manilkara chicle, and trying to use the stuff as rubber on carriage tires.

Thomas Adams, the American assigned to aid Santa Anna while he was in the US, also experimented with chicle as a substitute for rubber. He bought a ton of the stuff from the General, but his experiments would likewise prove unsuccessful. Instead, Adams helped to found the American chewing gum industry with a product called “Chiclets”.

Eminent domain exists for a purpose, but the most extreme care should be taken in its use. Plaintiffs argued that this was not a “public use”, but rather a private corporation using the power of government to take their homes for economic development, a violation of both the takings clause of the 5th amendment and the due process clause of the 14th.

Eminent domain exists for a purpose, but the most extreme care should be taken in its use. Plaintiffs argued that this was not a “public use”, but rather a private corporation using the power of government to take their homes for economic development, a violation of both the takings clause of the 5th amendment and the due process clause of the 14th. Clarence Thomas took an originalist view, stating that the majority opinion had confused “Public Use” with “Public Purpose”. “Something has gone seriously awry with this Court’s interpretation of the Constitution“, Thomas wrote. “Though citizens are safe from the government in their homes, the homes themselves are not“. Antonin Scalia concurred, seeing any tax advantage to the municipality as secondary to the taking itself.

Clarence Thomas took an originalist view, stating that the majority opinion had confused “Public Use” with “Public Purpose”. “Something has gone seriously awry with this Court’s interpretation of the Constitution“, Thomas wrote. “Though citizens are safe from the government in their homes, the homes themselves are not“. Antonin Scalia concurred, seeing any tax advantage to the municipality as secondary to the taking itself.

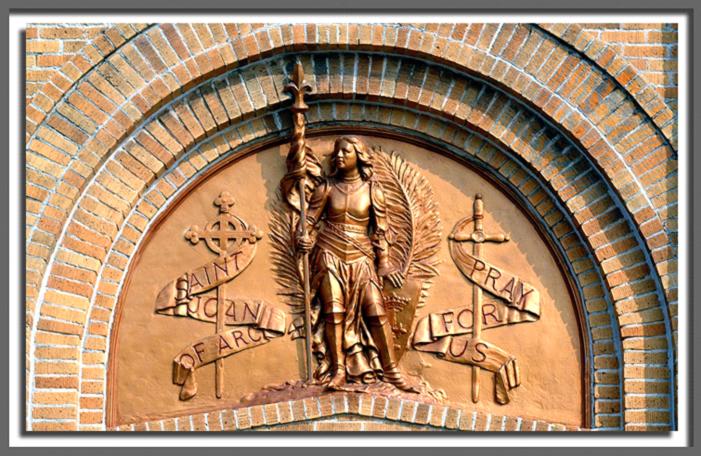

Some 70 charges were made against her by the pro-English Bishop of Beauvais, Pierre Cauchon, including witchcraft, heresy, and perjury.

Some 70 charges were made against her by the pro-English Bishop of Beauvais, Pierre Cauchon, including witchcraft, heresy, and perjury. After fifteen such interrogations her inquisitors still had nothing on her, save for the wearing of soldier’s garb, and her visions. Yet, the outcome of her “trial” was already determined. She was found guilty of heresy, and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

After fifteen such interrogations her inquisitors still had nothing on her, save for the wearing of soldier’s garb, and her visions. Yet, the outcome of her “trial” was already determined. She was found guilty of heresy, and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

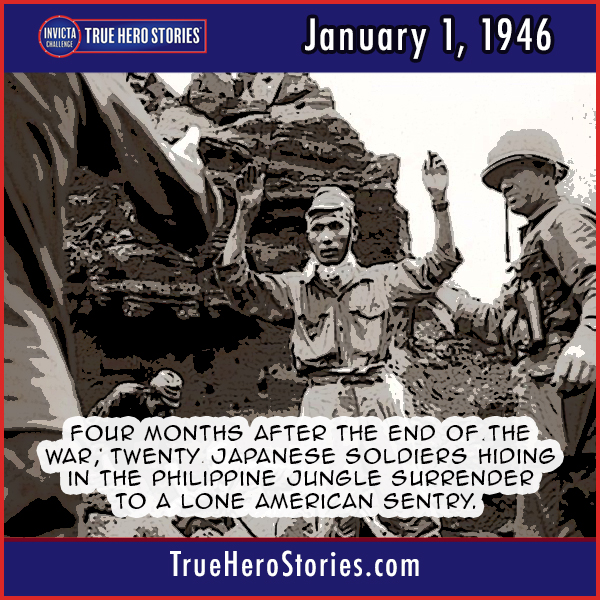

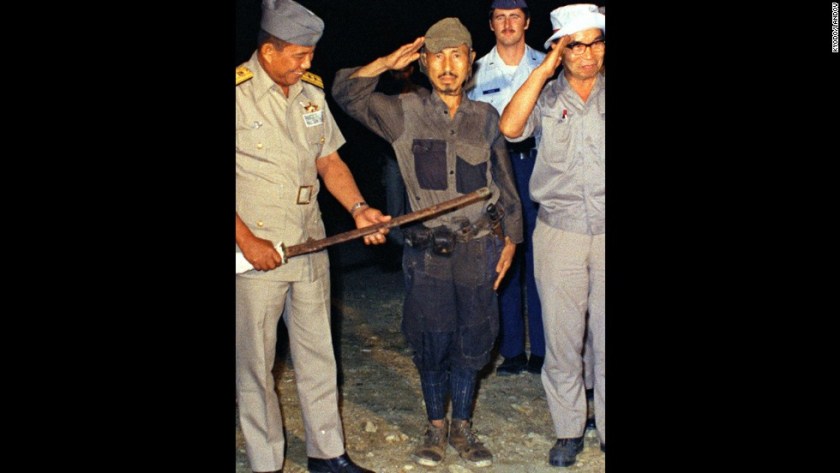

Imperial Japan would rage for another 33 years.

Imperial Japan would rage for another 33 years.

Several went on to fight for the Viet Minh against French troops in Indochina.

Several went on to fight for the Viet Minh against French troops in Indochina.

On February 7, the 71st Infantry and supporting tanks reached Ramree town where they found determined Japanese resistance, the town falling two days later. Naval forces blockaded small tributaries called “chaungs”, which the retreating Japanese used in their flight to the mainland. A Japanese air raid damaged an allied destroyer on the 11th as a flotilla of small craft crossed the strait, to rescue survivors of the garrison. By February 17, Japanese resistance had come to an end.

On February 7, the 71st Infantry and supporting tanks reached Ramree town where they found determined Japanese resistance, the town falling two days later. Naval forces blockaded small tributaries called “chaungs”, which the retreating Japanese used in their flight to the mainland. A Japanese air raid damaged an allied destroyer on the 11th as a flotilla of small craft crossed the strait, to rescue survivors of the garrison. By February 17, Japanese resistance had come to an end.

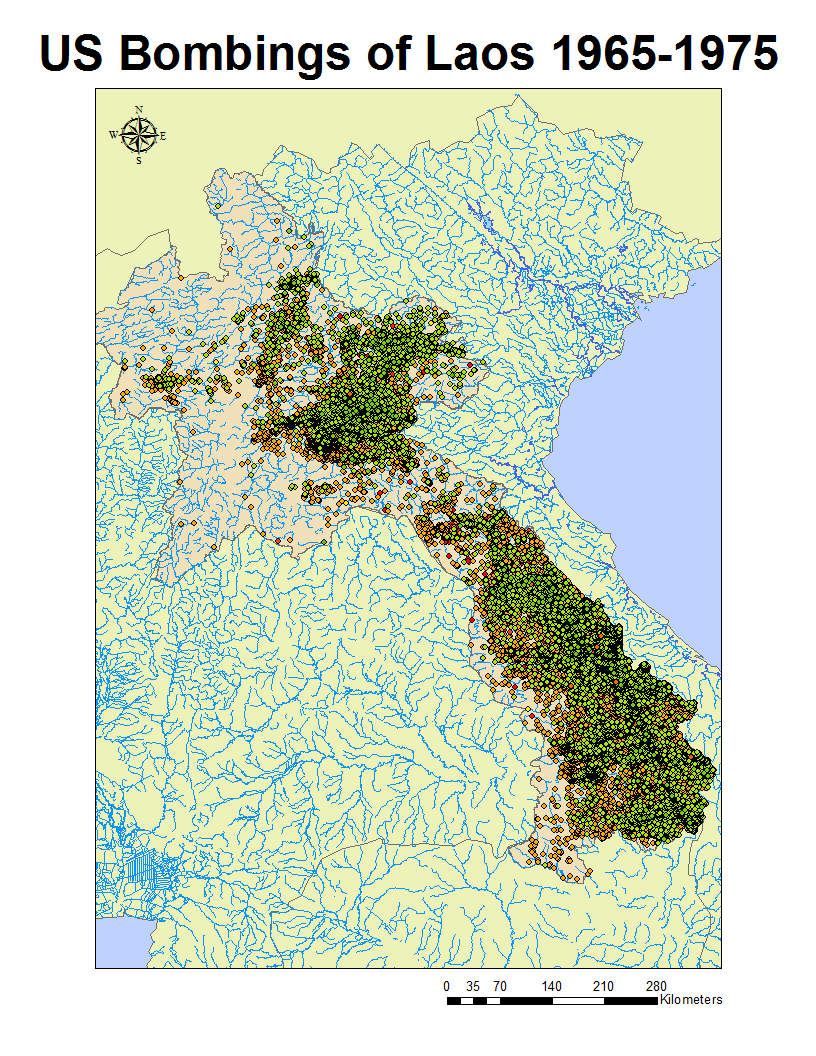

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

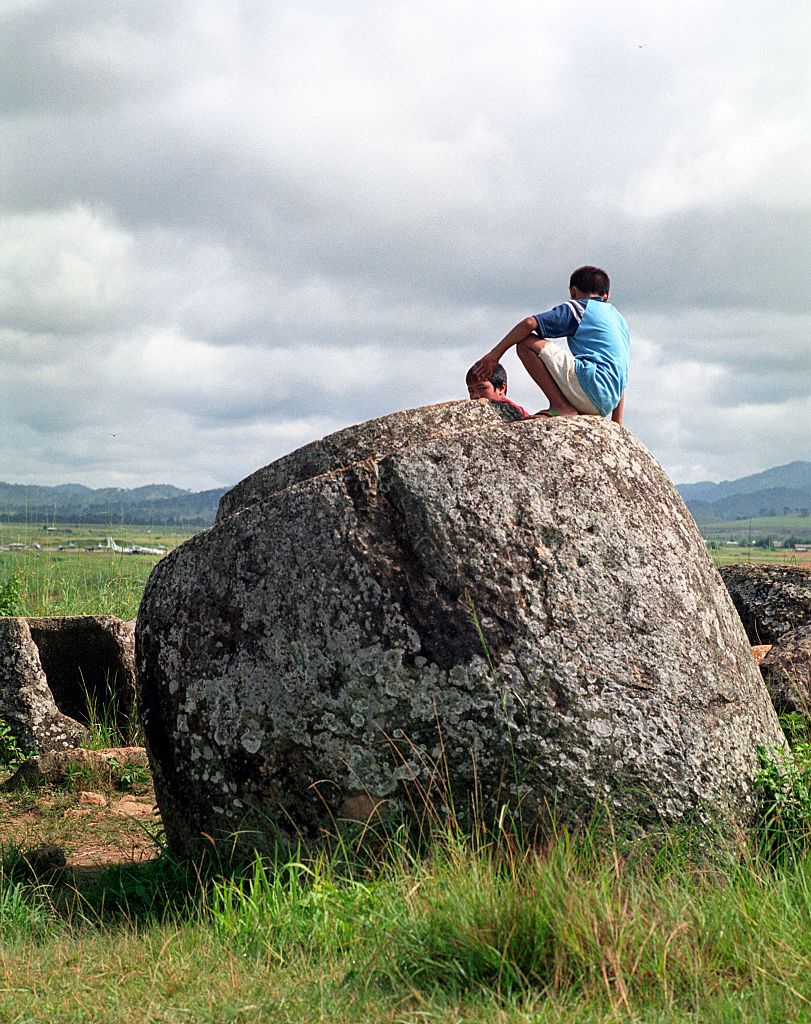

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

A second crew tested the submarine on October 15, this one including Horace Hunley himself. The submarine conducted a mock attack but failed to surface afterward, this time drowning all 8 crew members.

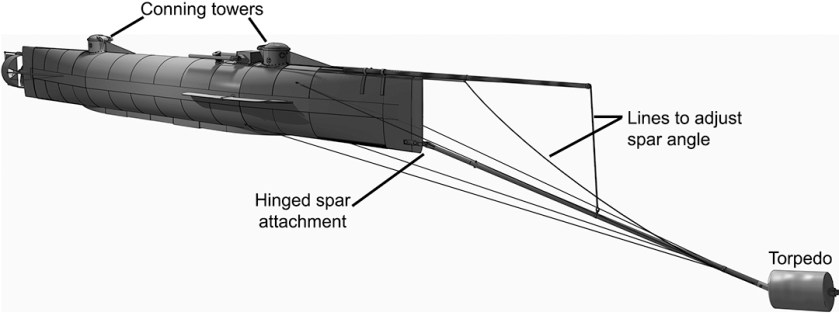

A second crew tested the submarine on October 15, this one including Horace Hunley himself. The submarine conducted a mock attack but failed to surface afterward, this time drowning all 8 crew members. Tide and current conditions in Charleston proved very different from those in Mobile. On several test runs, the torpedo floated out ahead of the sub. That wouldn’t do, so a spar was fashioned and mounted to the bow. At the end of the spar was a 137lb waterproof cask of powder, attached to a harpoon-like device with which Hunley would ram its target.

Tide and current conditions in Charleston proved very different from those in Mobile. On several test runs, the torpedo floated out ahead of the sub. That wouldn’t do, so a spar was fashioned and mounted to the bow. At the end of the spar was a 137lb waterproof cask of powder, attached to a harpoon-like device with which Hunley would ram its target.

On the coin, clearly showing signs of having been struck by a bullet, are inscribed these words:

On the coin, clearly showing signs of having been struck by a bullet, are inscribed these words:

On the evening of February 16, 1804, Decatur entered Tripoli Harbor with a force of 74 Marines. With them were five Sicilian volunteers, including pilot Salvador Catalano, who spoke fluent Arabic. Disguised as Maltese sailors and careful not to draw fire from shore batteries, Decatur’s force boarded the frigate, killing or capturing all but two of its Tripolitan crew. Decatur and his marines had hoped to sail Philadelphia out of harbor, but soon found she was in no condition to leave. Setting combustibles about the deck, they set the frigate ablaze. Ropes burned off, setting the Philadelphia adrift in the harbor. Loaded cannon cooked off as the blaze spread, firing random balls into the town. It must have been a sight, when gunpowder stores ignited and the entire ship exploded.

On the evening of February 16, 1804, Decatur entered Tripoli Harbor with a force of 74 Marines. With them were five Sicilian volunteers, including pilot Salvador Catalano, who spoke fluent Arabic. Disguised as Maltese sailors and careful not to draw fire from shore batteries, Decatur’s force boarded the frigate, killing or capturing all but two of its Tripolitan crew. Decatur and his marines had hoped to sail Philadelphia out of harbor, but soon found she was in no condition to leave. Setting combustibles about the deck, they set the frigate ablaze. Ropes burned off, setting the Philadelphia adrift in the harbor. Loaded cannon cooked off as the blaze spread, firing random balls into the town. It must have been a sight, when gunpowder stores ignited and the entire ship exploded.

Mickey Dugan was born on February 17, 1895, on the wrong side of the tracks. A wise-cracking street urchin with a “sunny disposition”, Mickey was the kind of street kid you’d find in New York’s turn-of-the-century slums, maybe hawking newspapers. “Extra, Extra, read all about it!”

Mickey Dugan was born on February 17, 1895, on the wrong side of the tracks. A wise-cracking street urchin with a “sunny disposition”, Mickey was the kind of street kid you’d find in New York’s turn-of-the-century slums, maybe hawking newspapers. “Extra, Extra, read all about it!” Outcault’s “Hogan’s Alley” strip, one of the first regular Sunday newspaper cartoons in the country, became colorized in May of 1895. For the first time, Mickey Dugan’s oversized, hand-me-down nightshirt was depicted in yellow. Soon, the character was simply known as “the Yellow kid”.

Outcault’s “Hogan’s Alley” strip, one of the first regular Sunday newspaper cartoons in the country, became colorized in May of 1895. For the first time, Mickey Dugan’s oversized, hand-me-down nightshirt was depicted in yellow. Soon, the character was simply known as “the Yellow kid”. We hear a lot today about “fake news”, but that’s nothing new. Circulation wars were white hot in those days, competing newspapers using anything possible to get an edge. Real-life street urchins hawked lurid headlines, heavy on scandal-mongering and light on verifiable fact. Whatever it took, to increase circulation.

We hear a lot today about “fake news”, but that’s nothing new. Circulation wars were white hot in those days, competing newspapers using anything possible to get an edge. Real-life street urchins hawked lurid headlines, heavy on scandal-mongering and light on verifiable fact. Whatever it took, to increase circulation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.