The Super Carrier USS Forrestal departed Norfolk in June 1967, with a crew of 552 officers and 4,988 enlisted men. Sailing around the horn of Africa, she stopped briefly at Leyte Pier in the Philippines, before sailing on to “Yankee Station” in the South China Sea, arriving on July 25.

Before the cruise, damage control firefighting teams were shown training films of Navy ordnance tests, demonstrating how a 1000-lb bomb could be directly exposed to a jet fuel fire for a full 10 minutes. Tests were conducted using the new Mark 83 bomb, featuring a thicker, heat resistant wall compared with older munitions, and “H6” explosive, designed to burn off at high temperatures, like an enormous sparkler.

Along with Mark 83s, ordnance resupply had included sixteen AN-M65A1 “Fat Boy” bombs, Korean war era surplus intended to be used on the second bombing runs of the 29th. These were thinner skinned than the newer ordnance, armed with 10+ year-old “Composition B” explosive. Already far more sensitive to heat and shock than the newer ordnance, composition B becomes more volatile as the explosive ages. The stuff becomes more powerful as well, as much as 50%, by weight.

These older bombs were way past their “sell-by” date, having spent the better part of the last ten years in the heat and humidity of Subic Bay depots. Ordnance officers wanted nothing to do with the Fat Boys, with their rusting shells leaking paraffin, and rotted packaging. Some had production date stamps as early as 1953.

These older bombs were way past their “sell-by” date, having spent the better part of the last ten years in the heat and humidity of Subic Bay depots. Ordnance officers wanted nothing to do with the Fat Boys, with their rusting shells leaking paraffin, and rotted packaging. Some had production date stamps as early as 1953.

Handlers feared the old bombs might spontaneously detonate from the shock of a catapult takeoff.

In 1967, the carrier bombing campaign was the longest and most intense such effort in US Naval history. Over the preceding four days, Forrestal had already launched 150 sorties against targets in North Vietnam. Combat operations were outpacing production, using Mark 35s faster than they could be replaced.

When Forrestal met the ammunition ship Diamond Head on the 28th, the choice was to take on the Fat Boys, or cancel the second wave of attacks scheduled for the following day.

In addition to the bombs, ground attack aircraft were armed with 5″ “Zuni” unguided rockets, carried four at a time in under-wing rocket packs. Known for electrical malfunctions and accidental firing, standard Naval procedure required electrical pigtails to be connected, at the catapult.

In addition to the bombs, ground attack aircraft were armed with 5″ “Zuni” unguided rockets, carried four at a time in under-wing rocket packs. Known for electrical malfunctions and accidental firing, standard Naval procedure required electrical pigtails to be connected, at the catapult.

Ordnance officers found this slowed the launch rate and deviated from standard procedure, connecting pigtails while aircraft were still, “in the pack”. The table was set, for disaster.

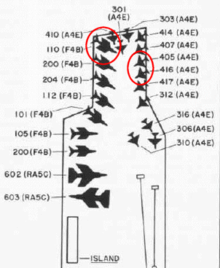

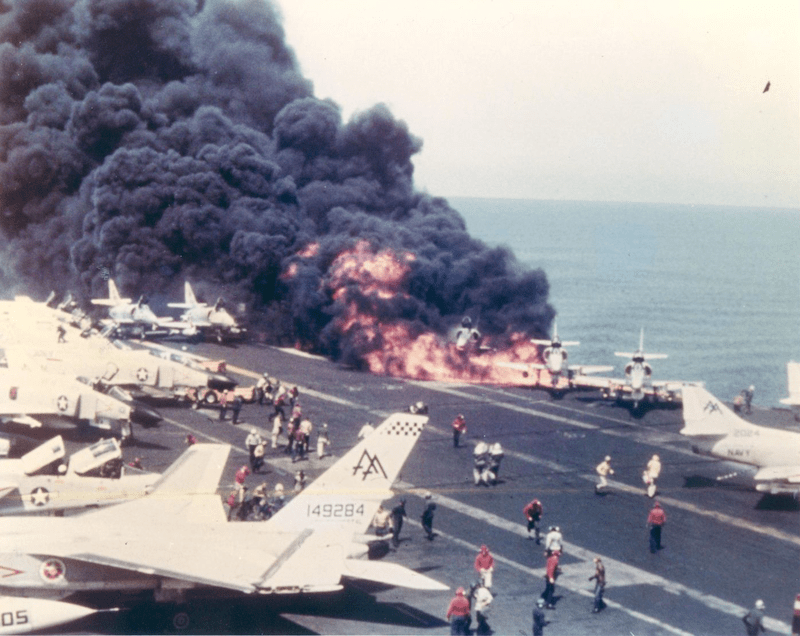

At 10:50-am local time, preparations were underway for the second strike of the day. Twenty-seven aircraft were on deck, fully loaded with fuel, ammunition, bombs and rockets. An electrical malfunction fired a Zuni rocket 100′ across the flight deck, severing the arm of one crew member and into the 400-gallon external fuel tank of an A-4E Skyhawk, awaiting launch.

The rocket’s safety mechanism prevented the weapon from exploding, but the A-4’s torn fuel tank was spewing flaming jet fuel onto the deck. Other tanks soon overheated and exploded, adding to the conflagration.

In WW2, virtually all American carrier crew were trained firefighters. This changed over time and, by 1967, the United States Navy had adopted the Japanese method at Midway, relying instead on specialized and highly trained damage control and fire fighting teams.

Damage Control Team #8 came into action immediately, as Chief Gerald Farrier spotted one of the Fat Boy bombs turning cherry red in the flames. Farrier was working without benefit of protective clothing, there had been no time. Farrier held his PKP fire extinguisher on the 1000-lb bomb, hoping to keep it cool enough to prevent its cooking off as his team brought the conflagration under control.

Firefighters were confident that their ten-minute window would hold as they fought the flames, but the composition B explosives proved as unstable as the ordnance people had feared. Farrier “simply disappeared” in the first of a dozen or more explosions, in the first few minutes of the fire. By the third such explosion, Damage Control Team #8 had all but ceased to exist.

Future United States Senator John McCain managed to scramble out of his cockpit and down the fuel probe. Lieutenant Commander Fred White made it out of his own aircraft a split-second later, but he was killed in that first explosion.

The port quarter of the Forrestal ceased to exist in the violence of the explosions, office furniture thrown to the floor as much as five decks below. Huge holes were torn into the flight deck while a cataract of flaming jet fuel, some 40,000 US gallons of the stuff, poured through ventilation ducts and into living quarters below.

Ninety-one crew members were killed below decks, by explosion or fire.

With trained firefighters now dead or incapacitated, sailors and marines fought heroically to bring the fire under control, though that sometimes made matters worse. Without training or knowledge of fire fighting, hose teams sprayed seawater, some washing away retardant foam being used to smother the flames.

With the life of the carrier itself at stake, tales of incredible courage, were commonplace. Medical officers worked for hours in the most dangerous conditions imaginable. Explosive ordnance demolition officer LT(JG) Robert Cates “noticed that there was a 500-pound bomb and a 750-pound bomb in the middle of the flight deck… that were still smoking. They hadn’t detonated or anything; they were just setting there smoking. So I went up and defused them and had them jettisoned.” Sailors volunteered to be lowered through the flight decks into flaming and smoked-filled compartments, to defuse live bombs.

The destroyer USS George K. MacKenzie plucked men out of the water as the destroyer USS Rupertus maneuvered alongside for 90 minutes, directing on-board fire hoses at the burning flight and hangar decks.

Throughout the afternoon, crew members rolled 250-pound and 500-pound bombs across the decks, and over the side. The major fire on the flight deck was brought under control within four hours but fires burning below decks would not be declared out until 4:00am the following day.

Panel 24E of the Vietnam Memorial records the names of 134 crewmen who died in the conflagration. Another 161 were seriously injured. 26 aircraft were destroyed and another 40, damaged. Damage to the Forrestal itself exceeded $72 million, equivalent to over $415 million today.

Gary Childs of Paxton Massachusetts, my uncle, was among the hundreds of sailors and marines who fought to bring the fire under control. Gary was below decks when the fire broke out, leaving moments before his quarters were engulfed in flames. Only by that slimmest of margins did any number of sailors aboard the USS Forrestal, escape being #135.

Gary Childs of Paxton Massachusetts, my uncle, was among the hundreds of sailors and marines who fought to bring the fire under control. Gary was below decks when the fire broke out, leaving moments before his quarters were engulfed in flames. Only by that slimmest of margins did any number of sailors aboard the USS Forrestal, escape being #135.

German submarine wolf packs had already sunk several ships in these waters. Late on the night of February 2, one of the Cutters flashed flashed the light signal “we’re being followed”.

German submarine wolf packs had already sunk several ships in these waters. Late on the night of February 2, one of the Cutters flashed flashed the light signal “we’re being followed”. Those who could escape scrambled onto the deck, injured, disoriented, many still in their underwear as they emerged into the cold and darkness.

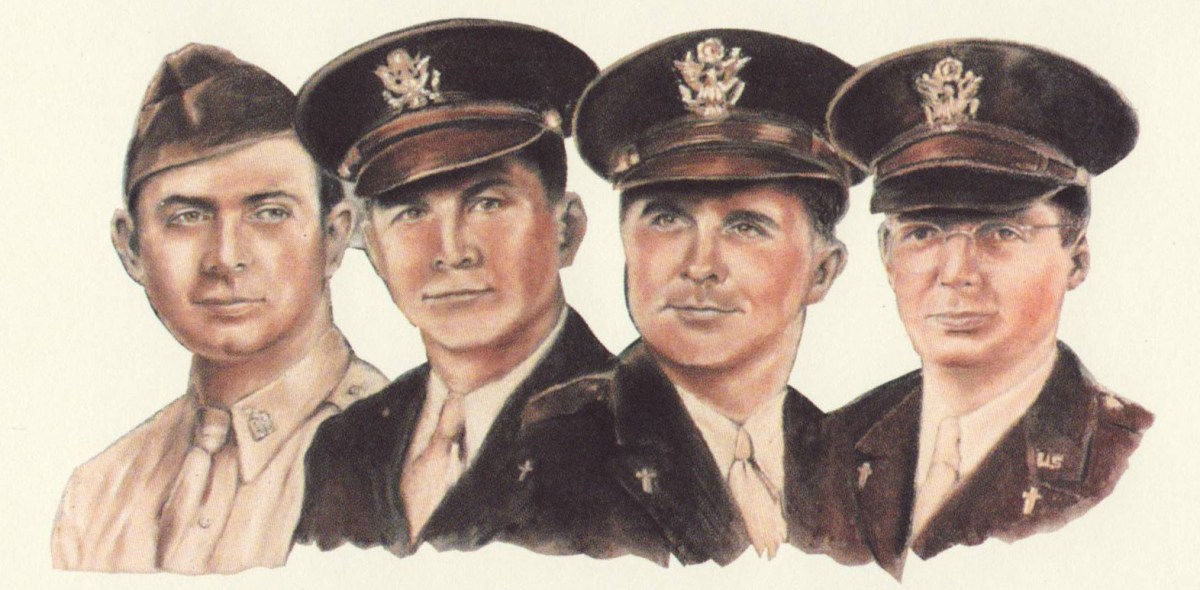

Those who could escape scrambled onto the deck, injured, disoriented, many still in their underwear as they emerged into the cold and darkness. Dorchester was listing hard to starboard and taking on water fast, with only 20 minutes to live. Port side lifeboats were inoperable due to the ship’s angle. Men jumped across the void into those on the starboard side, overcrowding some to the point of capsize. Only two of fourteen lifeboats launched successfully.

Dorchester was listing hard to starboard and taking on water fast, with only 20 minutes to live. Port side lifeboats were inoperable due to the ship’s angle. Men jumped across the void into those on the starboard side, overcrowding some to the point of capsize. Only two of fourteen lifeboats launched successfully. Rushing back to the scene, coast guard cutters found themselves in a sea of bobbing red lights, the water-activated emergency strobe lights of individual life jackets. Most marked the location of corpses. Of the 904 on board, the Coast Guard plucked 230 from the water, alive.

Rushing back to the scene, coast guard cutters found themselves in a sea of bobbing red lights, the water-activated emergency strobe lights of individual life jackets. Most marked the location of corpses. Of the 904 on board, the Coast Guard plucked 230 from the water, alive. John 15:13 teaches us, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”. Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew when he gave away his only hope for survival, Father Washington did not ask for a Catholic. Neither minister Fox nor Poling asked for a Protestant. Each gave his life jacket to the nearest man.

John 15:13 teaches us, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”. Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew when he gave away his only hope for survival, Father Washington did not ask for a Catholic. Neither minister Fox nor Poling asked for a Protestant. Each gave his life jacket to the nearest man.

During her service to the United States Navy, West Point was awarded the American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and World War II Victory Medal.

During her service to the United States Navy, West Point was awarded the American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and World War II Victory Medal. She was in terrible condition and her refit nowhere near complete when America set sail on her first cruise on June 30, 1978. There was rusted metal, oil soaked rags and backed up sewage. There were filthy mattresses and soiled linens. One woman later said, she was a “floating garbage can.” The angriest of customers actually got into fist fights with members of the crew. There were so many complaints the ship finally turned back, still within sight of the Statue of Liberty.

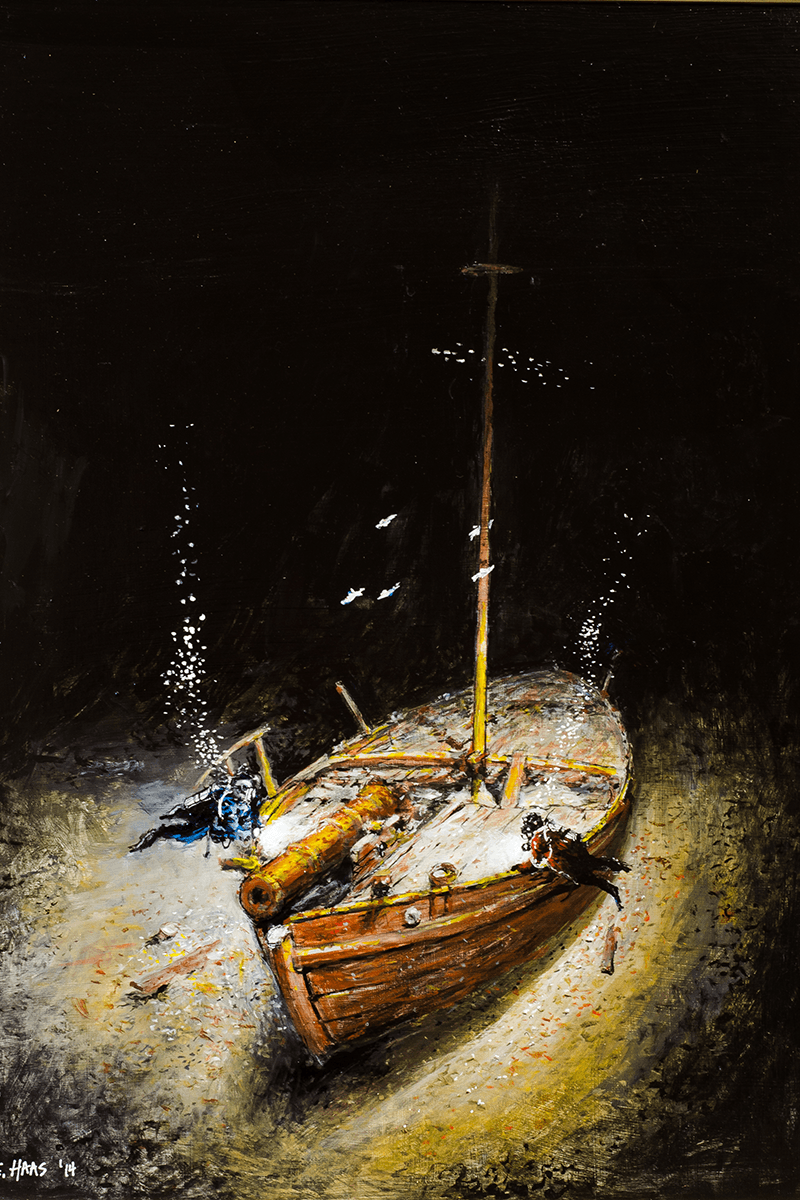

She was in terrible condition and her refit nowhere near complete when America set sail on her first cruise on June 30, 1978. There was rusted metal, oil soaked rags and backed up sewage. There were filthy mattresses and soiled linens. One woman later said, she was a “floating garbage can.” The angriest of customers actually got into fist fights with members of the crew. There were so many complaints the ship finally turned back, still within sight of the Statue of Liberty. Sold yet again in 1993 and renamed the American Star, the new owners planned to convert her to a five-star hotel ship off Phuket, Thailand. A planned 100 day tow began on New Year’s Eve of 1993, but the lines broke. On January 17, 1994, the former SS America was adrift in foul seas, running aground in the Canary Islands the following day. Discussions of salvage operations were soon squashed, as the ship broke in two in the pounding surf.

Sold yet again in 1993 and renamed the American Star, the new owners planned to convert her to a five-star hotel ship off Phuket, Thailand. A planned 100 day tow began on New Year’s Eve of 1993, but the lines broke. On January 17, 1994, the former SS America was adrift in foul seas, running aground in the Canary Islands the following day. Discussions of salvage operations were soon squashed, as the ship broke in two in the pounding surf. The National WWII Museum in New Orleans reports on its website that the men and women who fought and won the great conflict are now passing at a rate of 550 per day. How many, I wonder, might think back and remember passage on the most successful troop transport of their day.

The National WWII Museum in New Orleans reports on its website that the men and women who fought and won the great conflict are now passing at a rate of 550 per day. How many, I wonder, might think back and remember passage on the most successful troop transport of their day.

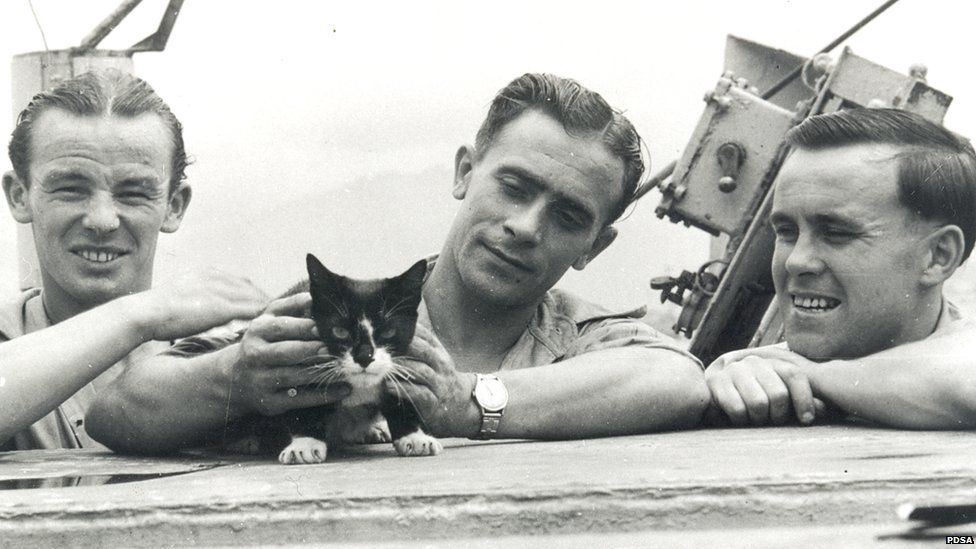

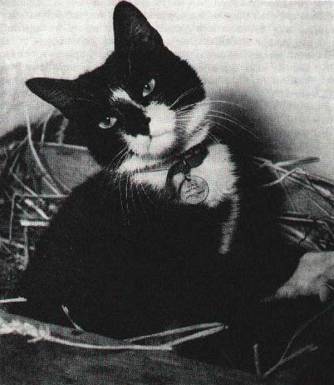

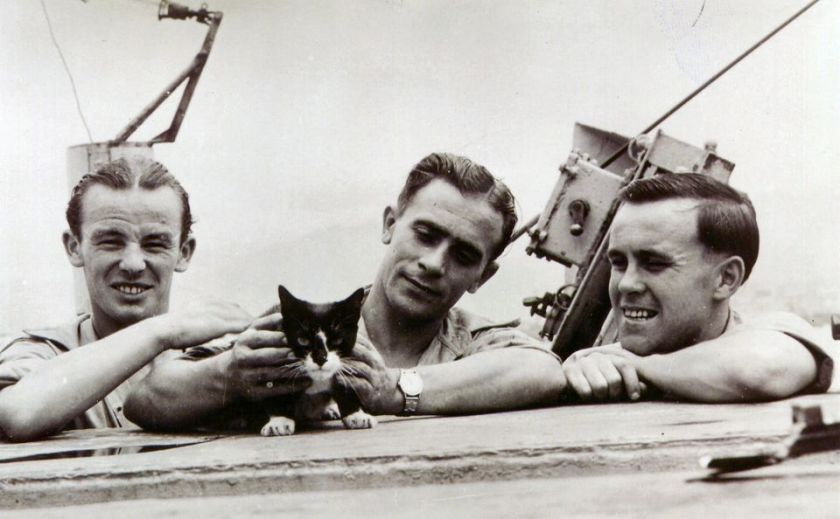

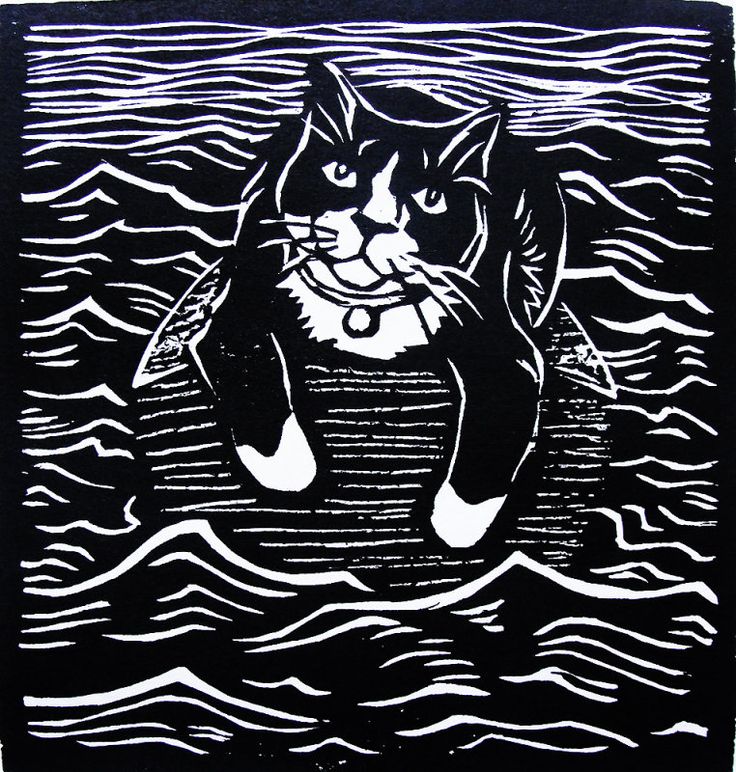

Simon earned the admiration of the Amethyst crew, with his prowess as a rat killer. Seamen learned to check their beds for “presents” of dead rats while Simon himself could usually be found, curled up and sleeping in the Captain’s hat.

Simon earned the admiration of the Amethyst crew, with his prowess as a rat killer. Seamen learned to check their beds for “presents” of dead rats while Simon himself could usually be found, curled up and sleeping in the Captain’s hat.

All but unseen amidst the economic devastation of World War 1, the domesticated animals of Great Britain were in desperate straits. Turn-of-the-century social reformer Maria Elizabeth “Mia” Dickin founded the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) in 1917, working to lighten the dreadful state of animal health in Whitechapel, London. To this day, the PDSA is one of the largest veterinary charities in the United Kingdom, conducting over a million free veterinary consultations, every year.

All but unseen amidst the economic devastation of World War 1, the domesticated animals of Great Britain were in desperate straits. Turn-of-the-century social reformer Maria Elizabeth “Mia” Dickin founded the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) in 1917, working to lighten the dreadful state of animal health in Whitechapel, London. To this day, the PDSA is one of the largest veterinary charities in the United Kingdom, conducting over a million free veterinary consultations, every year.

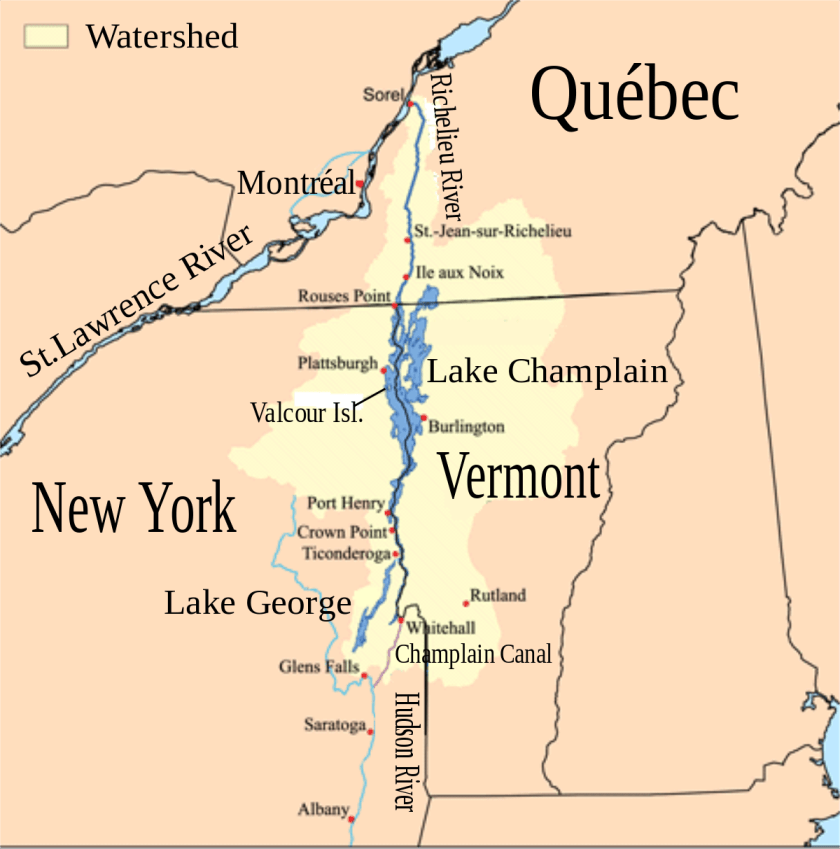

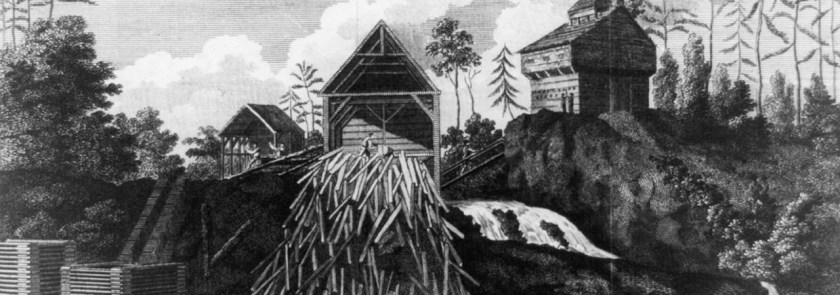

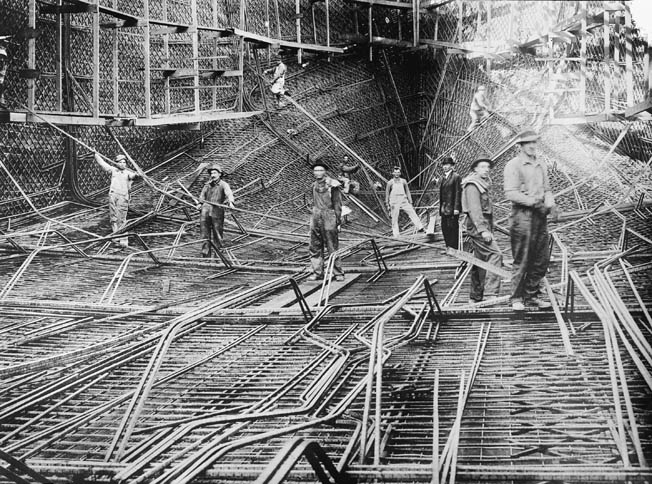

Hermanus Schuyler oversaw the effort, while military engineer Jeduthan Baldwin was in charge of outfitting. Gates asked General Benedict Arnold, an experienced ship’s captain, to spearhead the effort, explaining “I am intirely uninform’d as to Marine Affairs”.

Hermanus Schuyler oversaw the effort, while military engineer Jeduthan Baldwin was in charge of outfitting. Gates asked General Benedict Arnold, an experienced ship’s captain, to spearhead the effort, explaining “I am intirely uninform’d as to Marine Affairs”. As the two sides closed in the early days of October, General Arnold knew he was at a disadvantage. The element of surprise was going to be critical. Arnold chose a small strait to the west of Valcour Island, where he was hidden from the main part of the lake. There he drew his small fleet into a crescent formation, and waited.

As the two sides closed in the early days of October, General Arnold knew he was at a disadvantage. The element of surprise was going to be critical. Arnold chose a small strait to the west of Valcour Island, where he was hidden from the main part of the lake. There he drew his small fleet into a crescent formation, and waited.

Amethyst returned fire but it wasn’t long before she was disabled, run aground with most of her guns too high to return fire. The first salvo from the Communist guns exploded in the Captain’s quarters, mortally wounding Commander Skinner and badly injuring the ship’s cat.

Amethyst returned fire but it wasn’t long before she was disabled, run aground with most of her guns too high to return fire. The first salvo from the Communist guns exploded in the Captain’s quarters, mortally wounding Commander Skinner and badly injuring the ship’s cat.

The Amethyst incident resulted in the death of 47 British seamen with another 74, wounded. HMS Amethyst herself sustained heavy damage in the episode. The heavy cruiser HMS London, the destroyer HMS Consort and the sloop HMS Black Swan were also damaged.

The Amethyst incident resulted in the death of 47 British seamen with another 74, wounded. HMS Amethyst herself sustained heavy damage in the episode. The heavy cruiser HMS London, the destroyer HMS Consort and the sloop HMS Black Swan were also damaged.

The monarchical powers of Europe were quick to intervene. For the 32nd time since the Norman invasion of 1066, England and France once again found themselves in a state of war.

The monarchical powers of Europe were quick to intervene. For the 32nd time since the Norman invasion of 1066, England and France once again found themselves in a state of war.

You must be logged in to post a comment.