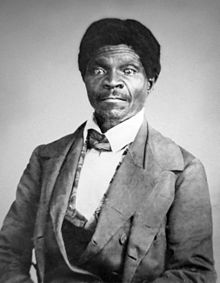

Dred Scott, his full name may have been “Etheldred”, was born into slavery in Southampton County, Virginia, sometime in the late 1790s. In 1818, Scott belonged to Peter Blow, who moved his family and six slaves to Alabama, to attempt a life of farming. The farm near Huntsville was unsuccessful and the Blow family gave up the effort, moving to St. Louis Missouri in 1830, to run a boarding house. Around this time, Dred Scott was sold to Dr. John Emerson, a surgeon serving in the United States Army.

As an army officer, Dr. Emerson moved about frequently, bringing Scott with him. In 1837, Emerson moved to Fort Snelling in the free territory of Wisconsin, now Minnesota. There, Scott met and married Harriet Robinson, a slave belonging to fellow army doctor and Justice of the Peace, Lawrence Taliaferro. Taliaferro, who presided over the ceremony, transferred Harriet to Emerson, who continued to regard the couple as his slaves. Emerson moved away later that year, leaving the Scotts behind to be leased by other officers.

The following year, Dr. Emerson married Eliza Irene Sanford, and sent for the Scotts to rejoin him in Fort Jesup, in Louisiana. Harriett gave birth to a daughter while on a steamboat on the Mississippi, between the free state of Illinois and the Iowa district of the Wisconsin Territory.

Dr. Emerson died in 1842, leaving his estate to his wife Eliza, who continued to lease the Scotts out as hired slaves.

Dr. Emerson died in 1842, leaving his estate to his wife Eliza, who continued to lease the Scotts out as hired slaves.

Four years later, Scott attempted to buy his freedom for the sum of $300, equivalent to about $8,000 today. Mrs. Emerson declined the offer and Scott took legal recourse. By this time, Dred and Harriett Scott had two daughters, who were approaching an age where their value would be greatly increased, should they be sold as slaves. Wanting to keep his family together, Scott sued.

Ironically, Dred Scott’s suit in state court, Scott v. Emerson, was financially backed by three now-adult Blow children, who had since become abolitionists. The legal position stood on solid ground, based on the doctrine “Once free, always free”. The Scott family had resided in free states and territories for two years, and their eldest daughter was born on the Mississippi River, between a free state and a free territory.

The verdict went against Scott but the judge ordered a retrial, which was held in January, 1850. This time, the jury ruled in favor of Dred Scott’s freedom. Emerson appealed and the Missouri supreme court struck down the lower court ruling, along with 28 years of Missouri precedent.

By 1853, Eliza Emerson had remarried and moved to Massachusetts, transferring ownership of the Scott family to her brother, John Sanford. Scott sued in federal district court, on the legal basis that the federal courts held “diversity jurisdiction”, since Sanford lived in one state (New York), and Scott in another (Missouri). Dred Scott lost once again and appealed to the United States Supreme Court, a clerical misspelling erroneously recording the case as Dred Scott v. Sandford.

On March 6, 1857, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the 7-2 majority opinion, enunciating one of the stupidest decisions, in the history of American jurisprudence:

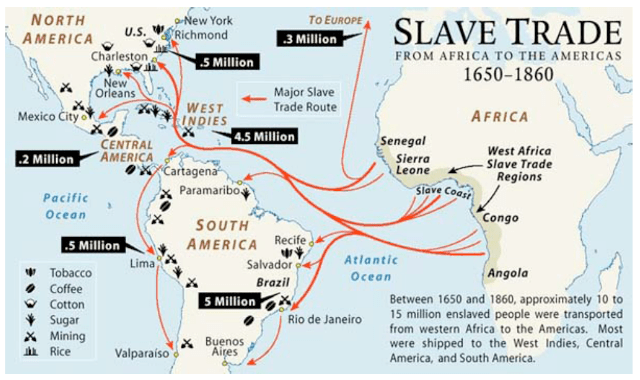

“[Americans of African ancestry] had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold, and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic, whenever a profit could be made by it”.

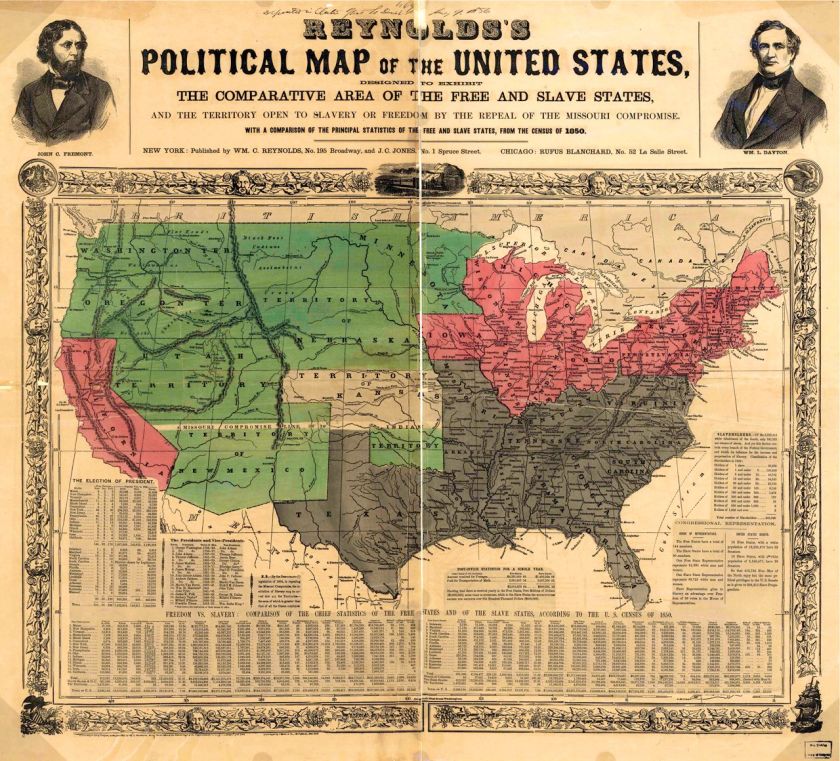

The highest court in the land had ruled that slaves were private property and not citizens, with no right to legal recourse. Furthermore, the United States Congress had erred in attempting to regulate slavery in the territories, and had no right to revoke the property rights of a slave owner, based on his place of residence.

The response to the SCOTUS opinion was immediate, and vehement. Rather than settle the issue of slavery, the decision inflamed public opinion, dividing an already fractured country, further. Frederick Douglass assailed Chief Justice Taney’s opinion, noting that:

“We are now told, in tones of lofty exultation, that the day is lost all lost and that we might as well give up the struggle. The highest authority has spoken. The voice of the Supreme Court has gone out over the troubled waves of the National Conscience, saying peace, be still . . . The Supreme Court of the United States is not the only power in this world. It is very great, but the Supreme Court of the Almighty is greater”.

The Supreme Court had spoken, but the Dred Scott story was far from over. Eliza Irene Emerson’s new husband was Calvin C. Chaffee, a member of the United States Congress, and an abolitionist.

Following the Dred Scott decision, the Chaffees deeded the Scott family over to Henry Taylor Blow, now a member of the United States House of Representatives from Missouri’s 2nd Congressional district, who manumitted the family on May 26. Dred Scott had lost at virtually every turn, only to win his freedom at the hands of the family which had once held him enslaved.

For Harriett and the two Scott daughters, it was the best of all possible outcomes. For Scott himself, freedom was short-lived. Dred Scott died of tuberculosis, the following year.

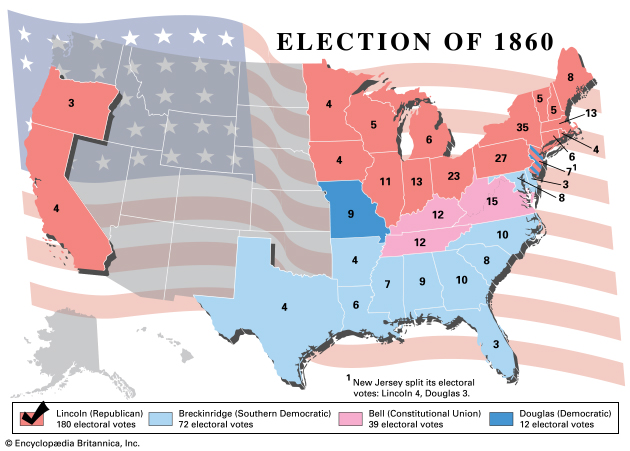

Nationally, the Dred Scott decision had the effect of hardening enmities already nearing white-hot, increasing animosities within and between pro- and anti-slavery factions in North and South, alike. Politically, the Democratic party was broken into factions and severely weakened, while the fledgling Republican party was strengthened, as the nation was inexorably drawn to Civil War.

The issue of Black citizenship was settled in 1868, via Section 1 of the 14th Amendment, which states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside …”

Dred Scott is buried in the Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. The marker next to his headstone reads: “In Memory Of A Simple Man Who Wanted To Be Free.”

Far-left anarchists mailed no fewer than 36 dynamite bombs to prominent political and business leaders in April 1919, alone. In June, another nine far more powerful bombs destroyed churches, police stations and businesses.

Far-left anarchists mailed no fewer than 36 dynamite bombs to prominent political and business leaders in April 1919, alone. In June, another nine far more powerful bombs destroyed churches, police stations and businesses. To this day there are those who describe the period as the “First Red Scare”, as a way to ridicule the concerns of the era. The criticism seems unfair. The thing about history, is that we know how their story ends. The participants don’t, any more than we know what the future holds for ourselves.

To this day there are those who describe the period as the “First Red Scare”, as a way to ridicule the concerns of the era. The criticism seems unfair. The thing about history, is that we know how their story ends. The participants don’t, any more than we know what the future holds for ourselves.

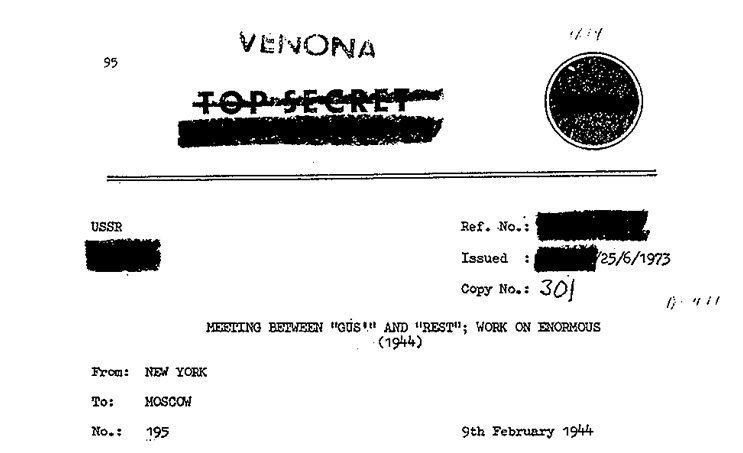

Before defecting from the Left, Chambers had secreted documents and microfilms, some of which he hid inside a pumpkin at his Maryland farm. The collection was known as the “Pumpkin Papers”, consisting of incriminating documents, written in what appeared to Hiss’ own hand, or typed on his Woodstock no. 230099 typewriter.

Before defecting from the Left, Chambers had secreted documents and microfilms, some of which he hid inside a pumpkin at his Maryland farm. The collection was known as the “Pumpkin Papers”, consisting of incriminating documents, written in what appeared to Hiss’ own hand, or typed on his Woodstock no. 230099 typewriter. Hiss’ theory never explained why Chambers side needed another typewriter, if they’d had the original long enough to mimic its imperfections with a second.

Hiss’ theory never explained why Chambers side needed another typewriter, if they’d had the original long enough to mimic its imperfections with a second.

Eminent domain exists for a purpose, but the most extreme care should be taken in its use. Plaintiffs argued that this was not a “public use”, but rather a private corporation using the power of government to take their homes for economic development, a violation of both the takings clause of the 5th amendment and the due process clause of the 14th.

Eminent domain exists for a purpose, but the most extreme care should be taken in its use. Plaintiffs argued that this was not a “public use”, but rather a private corporation using the power of government to take their homes for economic development, a violation of both the takings clause of the 5th amendment and the due process clause of the 14th. Clarence Thomas took an originalist view, stating that the majority opinion had confused “Public Use” with “Public Purpose”. “Something has gone seriously awry with this Court’s interpretation of the Constitution“, Thomas wrote. “Though citizens are safe from the government in their homes, the homes themselves are not“. Antonin Scalia concurred, seeing any tax advantage to the municipality as secondary to the taking itself.

Clarence Thomas took an originalist view, stating that the majority opinion had confused “Public Use” with “Public Purpose”. “Something has gone seriously awry with this Court’s interpretation of the Constitution“, Thomas wrote. “Though citizens are safe from the government in their homes, the homes themselves are not“. Antonin Scalia concurred, seeing any tax advantage to the municipality as secondary to the taking itself.

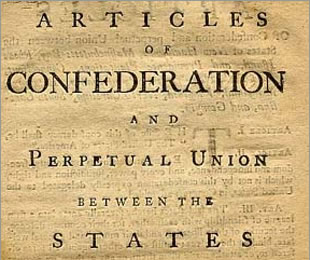

Twelve of the original thirteen states ratified these “Articles of Confederation” by February, 1779. Maryland held out for another two years, over land claims west of the Ohio River. In 1781, seven months before Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown, the 2nd Continental Congress formally ratified the Articles of Confederation. The young nation’s first governing document.

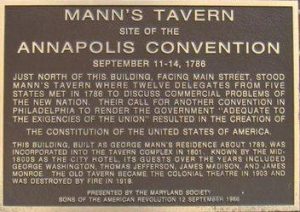

Twelve of the original thirteen states ratified these “Articles of Confederation” by February, 1779. Maryland held out for another two years, over land claims west of the Ohio River. In 1781, seven months before Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown, the 2nd Continental Congress formally ratified the Articles of Confederation. The young nation’s first governing document. The Union would probably have broken up, had not the Articles of Confederation been amended or replaced. Twelve delegates from five states met at Mann’s Tavern in Annapolis Maryland in September 1786, to discuss the issue. The decision of the Annapolis Convention was unanimous. Representatives from all the states were invited to send delegates to a constitutional convention in Philadelphia, the following May.

The Union would probably have broken up, had not the Articles of Confederation been amended or replaced. Twelve delegates from five states met at Mann’s Tavern in Annapolis Maryland in September 1786, to discuss the issue. The decision of the Annapolis Convention was unanimous. Representatives from all the states were invited to send delegates to a constitutional convention in Philadelphia, the following May. 25, 1787. The building is now known as Independence Hall, the same place where the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation were drafted.

25, 1787. The building is now known as Independence Hall, the same place where the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation were drafted.

On September 25, the first Congress adopted 12 amendments, sending them to the states for ratification.

On September 25, the first Congress adopted 12 amendments, sending them to the states for ratification.

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik was paroled in 1942, his criminal record making him 4F. “Registrant not acceptable for military service”. He took a job at the Montella Plumbing and Heating company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he met bookkeeper Antoinette Wisniewski, the woman who would later become his wife.

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik was paroled in 1942, his criminal record making him 4F. “Registrant not acceptable for military service”. He took a job at the Montella Plumbing and Heating company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he met bookkeeper Antoinette Wisniewski, the woman who would later become his wife. The rapid movement of the army during this period caused difficulty for many replacements, in finding their units. Edward Slovik and John Tankey finally caught up with the 109th on October 7. The following day, Slovik asked his company commander Captain Ralph Grotte for reassignment to a rear unit, saying he was “too scared” to be part of a rifle company. Grotte refused, confirming that, were he to run away, such an act would constitute desertion.

The rapid movement of the army during this period caused difficulty for many replacements, in finding their units. Edward Slovik and John Tankey finally caught up with the 109th on October 7. The following day, Slovik asked his company commander Captain Ralph Grotte for reassignment to a rear unit, saying he was “too scared” to be part of a rifle company. Grotte refused, confirming that, were he to run away, such an act would constitute desertion. “I, Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik, 36896415, confess to the desertion of the United States Army. At the time of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

“I, Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik, 36896415, confess to the desertion of the United States Army. At the time of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”. 1.7 million courts-martial were held during WWII, 1/3rd of all the criminal cases tried in the United States during the same period. The death penalty was rarely imposed. When it was, it was almost always in cases of rape or murder.

1.7 million courts-martial were held during WWII, 1/3rd of all the criminal cases tried in the United States during the same period. The death penalty was rarely imposed. When it was, it was almost always in cases of rape or murder.

Iva Ikuko Toguri was born in Los Angeles on July 4, 1916, the daughter of Japanese immigrants. She attended schools in Calexico and San Diego, returning to Los Angeles where she enrolled at UCLA, graduating in January, 1940 with a degree in zoology.

Iva Ikuko Toguri was born in Los Angeles on July 4, 1916, the daughter of Japanese immigrants. She attended schools in Calexico and San Diego, returning to Los Angeles where she enrolled at UCLA, graduating in January, 1940 with a degree in zoology. She called herself “Orphan Annie,” earning 150 yen per month (about $7.00 US). She wasn’t a professional radio personality, but many of those who recalled hearing her enjoyed the program, especially the music.

She called herself “Orphan Annie,” earning 150 yen per month (about $7.00 US). She wasn’t a professional radio personality, but many of those who recalled hearing her enjoyed the program, especially the music.

d’Aquino was sentenced to ten years and fined $10,000 for the crime of treason, only the seventh person in US history to be so convicted. She was released from the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia in 1956, having served six years and two months of her sentence.

d’Aquino was sentenced to ten years and fined $10,000 for the crime of treason, only the seventh person in US history to be so convicted. She was released from the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia in 1956, having served six years and two months of her sentence.

The United States had been in World War II for two years in 1943, when Claude Wickard, head of the War Foods Administration as well as Secretary of Agriculture, had the hare brained idea of banning sliced bread.

The United States had been in World War II for two years in 1943, when Claude Wickard, head of the War Foods Administration as well as Secretary of Agriculture, had the hare brained idea of banning sliced bread. Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution includes the “Commerce Clause”, permitting the Congress “To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes”. That’s it and, not surprisingly, the Federal District Court sided with the farmer.

Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution includes the “Commerce Clause”, permitting the Congress “To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes”. That’s it and, not surprisingly, the Federal District Court sided with the farmer. The Supreme Court, apparently afraid of President Roosevelt and his aggressive and illegal “

The Supreme Court, apparently afraid of President Roosevelt and his aggressive and illegal “ The stated reasons for the ban never did make sense. At various times, Wickard claimed that it was to conserve wax paper, wheat and steel, but one reason was goofier than the one before.

The stated reasons for the ban never did make sense. At various times, Wickard claimed that it was to conserve wax paper, wheat and steel, but one reason was goofier than the one before.

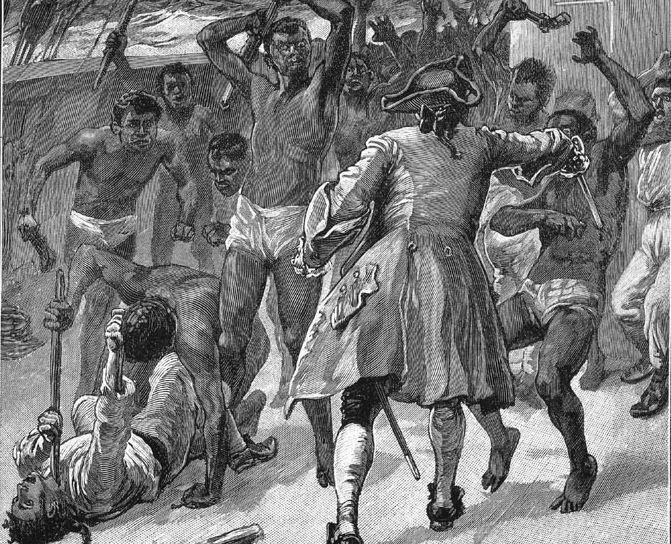

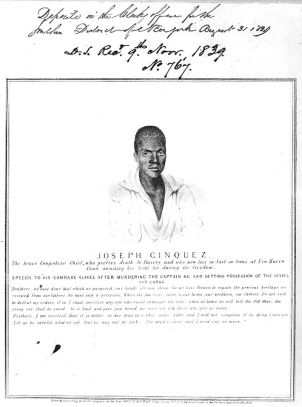

The district court trial which followed in Hartford determined that the Mendians’ papers were forged, and they should be returned to Africa. The cabin boy was ruled to be a slave and ordered returned to the Cubans, however he fled to New York with the help of abolitionists. He would live out the rest of his life as a free man.

The district court trial which followed in Hartford determined that the Mendians’ papers were forged, and they should be returned to Africa. The cabin boy was ruled to be a slave and ordered returned to the Cubans, however he fled to New York with the help of abolitionists. He would live out the rest of his life as a free man.

Sectional differences grew and sharpened in the years that followed. A member of Congress from Kentucky killed a fellow congressman from Maine. A Congressman from South Carolina all but beat a Massachusetts Senator to death with a

Sectional differences grew and sharpened in the years that followed. A member of Congress from Kentucky killed a fellow congressman from Maine. A Congressman from South Carolina all but beat a Massachusetts Senator to death with a

You must be logged in to post a comment.