He’s one of the most familiar faces on the supermarket shelf, right up there with Aunt Jemima and the Pillsbury Doughboy. That smiling, grandfatherly face with the red bandana and the tall chef’s hat. Like those other two a fictional character, the product of some brand development meeting, produced by the art department and focus-grouped by panels of consumers. As the story goes, the face behind the spaghetti and meatballs is the amalgamation of three names, the men behind the company: Boyd, Art and Dennis.

Only in this case, Boyd, Art & Dennis are the fictional characters. The face you remember pulling out from your old Dukes of Hazard lunchbox was quite real, I assure you. I’ve been best buddies with one of his relatives, for nigh on fifty years.

Some 25 million legal immigrants passed through Ellis Island between 1892 and 1924, among them Ettore Boiardi, Born in Piacenza, Italy, in 1897. By age 11, Boiardi was assistant chef at “La Croce Bianca“. The boy moved to Paris and then to London, honing his restaurant skills along the way. He arrived at Ellis Island on this day in 1914, age 16 and following his brothers Mario and Paolo to the kitchen of the Plaza Hotel in New York.

The Plaza Hotel menu was heavy on the French in those days and Ettore began to add some Italian. A little pasta, a nice tomato sauce. Before long, he was promoted to head chef.

The Plaza Hotel menu was heavy on the French in those days and Ettore began to add some Italian. A little pasta, a nice tomato sauce. Before long, he was promoted to head chef.

According to his New York Times obituary, Boiardi was so talented that President Woodrow Wilson chose the man to cater the reception for his marriage to his second wife Edith, in 1915.

After World War 1, Boiardi supervised a homecoming dinner at the White House, for 2,000 returning soldiers.

Boiardi’s spaghetti sauce was famous by this time. Ettore and his wife Helen opened a restaurant in Cleveland in 1926, Il Giardino d’Italia (The Garden of Italy), patrons often leaving with recipes for his sauces and samples, packed in cleaned milk bottles. It wasn’t long from there before the two were giving cooking classes and selling sauce, in milk jugs.

Maurice and Eva Weiner were patrons of the restaurant, and owners of a self-service grocery store chain. The couple helped develop large-scale canning operations. Before long Ettore and Mario bought farm acreage in Milton Pennsylvania, to raise tomatoes. In 1928, they changed the name on the label, making it easier for a tongue-tied non-Italian consumer, to pronounce. Calling himself “Hector” for the same reason, Ettore said “Everyone is proud of his own family name, but sacrifices are necessary for progress.”

Maurice and Eva Weiner were patrons of the restaurant, and owners of a self-service grocery store chain. The couple helped develop large-scale canning operations. Before long Ettore and Mario bought farm acreage in Milton Pennsylvania, to raise tomatoes. In 1928, they changed the name on the label, making it easier for a tongue-tied non-Italian consumer, to pronounce. Calling himself “Hector” for the same reason, Ettore said “Everyone is proud of his own family name, but sacrifices are necessary for progress.”

Meanwhile back in New York, Paolo (now calling himself “Paul”), made the acquaintance of one John Hartford, President of A&P Supermarkets. The Chef Boy-Ar-Dee company, was on the way.

During the Great Depression, Hector would tout the benefits of pasta, praising the stuff as an affordable, hot and nutritious meal for the whole family.

During the Great Depression, Hector would tout the benefits of pasta, praising the stuff as an affordable, hot and nutritious meal for the whole family.

World War II saw canning operations ramped up to 24/7 with the farm producing 20,000 tons of tomatoes at peak production and adding its own mushrooms, to the annual crop. The company employed 5,000 people producing a quarter-million cans, a day. Troops overseas couldn’t get enough of the stuff. For his contribution to the war effort, Hector Boiardi was honored with the Gold Star for Excellence, by the War Department.

Such rapid growth is never without problems, particularly for a family business. Hector sold the company to American Home Foods in 1946, for the reported sum of $5.96 million.

Boiardi stayed on as company spokesman and consultant until 1978. Forty years later, Advertising Age executive Barbara Lippert named the 1966 Young & Rubicam “Hooray for Beefaroni” ad patterned after the Running of the Bulls, as the the inspiration for Prince Spaghetti’s “Anthony” series and the famous “Hilltop” ad for Coca Cola.

One of the great “rags to riches” stories of our age, Hector Boiardi continued to develop new products until his death in 1987, amassing an estimated net worth of $60 million dollars. He is survived by his wife of 64 years and the couple’s one son, Mario. His face may be found smiling back from your grocery store shelf, to this day.

Wait…What?

Wait…What?

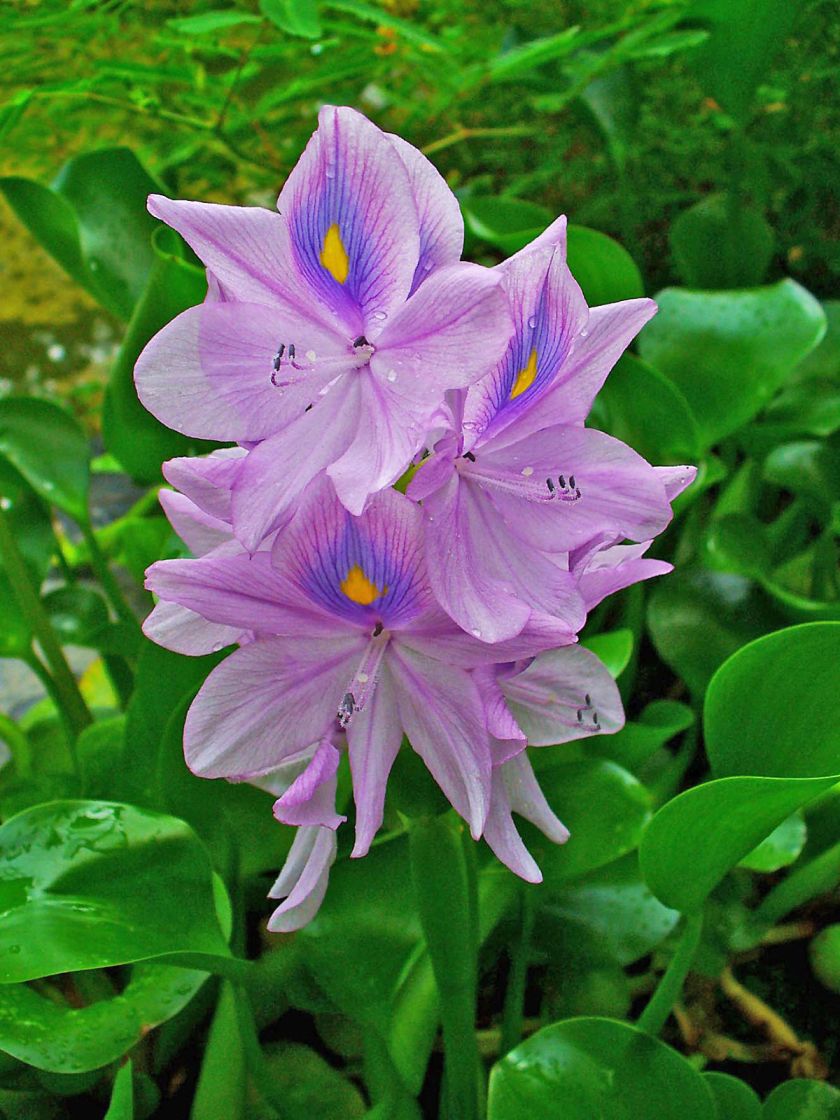

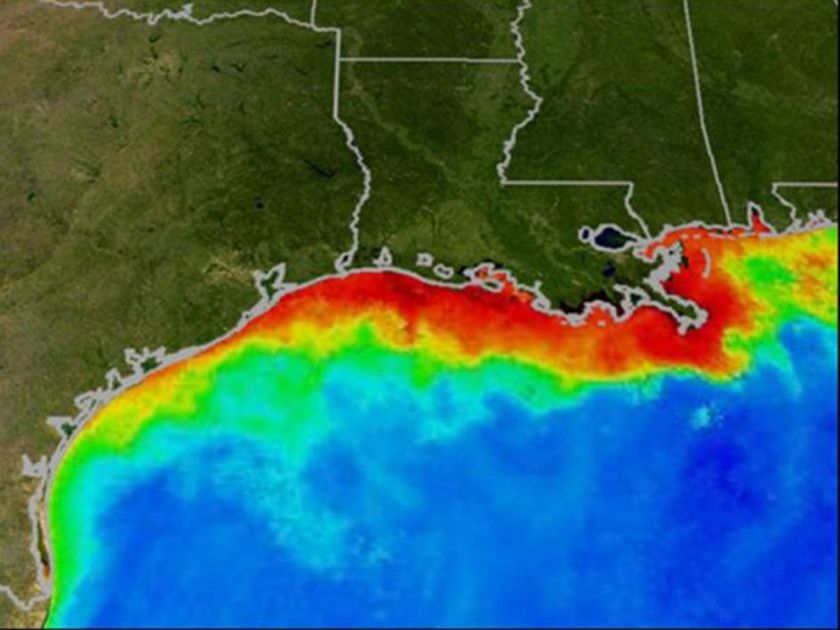

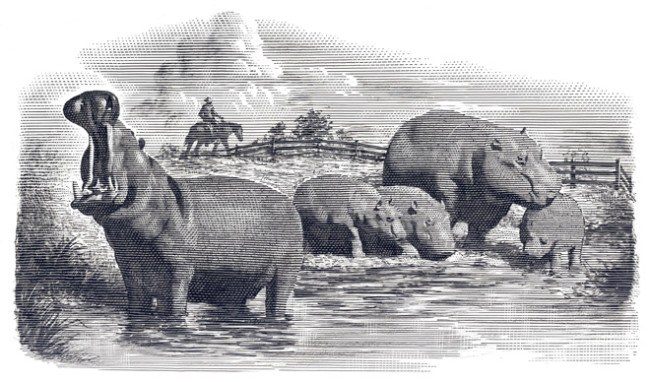

Be that at it as it may, the animal is a voracious herbivore, spending daylight hours at the bottom of rivers & lakes, happily munching on vegetation.

Be that at it as it may, the animal is a voracious herbivore, spending daylight hours at the bottom of rivers & lakes, happily munching on vegetation.

That golden future of Lippincott’s hippo herds roam only in the meadows and bayous of the imagination. Who knows, it may be for the best. I don’t know if any of us could see each other across the table. Not with a roast hippopotamus.

That golden future of Lippincott’s hippo herds roam only in the meadows and bayous of the imagination. Who knows, it may be for the best. I don’t know if any of us could see each other across the table. Not with a roast hippopotamus.

The Pilgrims left the Netherlands city of Leiden in 1620, hoping for rich farmland and congenial climate in the New World. Not the frozen, rocky soil of New England. Lookouts spotted the wind-swept shores of Cape Cod on November 9, 1620, and may have kept going, had they had enough beer. One Mayflower passenger wrote in his diary: “We could not now take time for further search… our victuals being much spent, especially our beer…”

The Pilgrims left the Netherlands city of Leiden in 1620, hoping for rich farmland and congenial climate in the New World. Not the frozen, rocky soil of New England. Lookouts spotted the wind-swept shores of Cape Cod on November 9, 1620, and may have kept going, had they had enough beer. One Mayflower passenger wrote in his diary: “We could not now take time for further search… our victuals being much spent, especially our beer…”

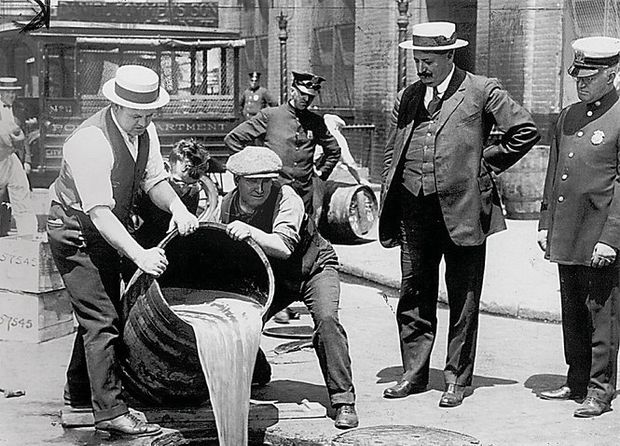

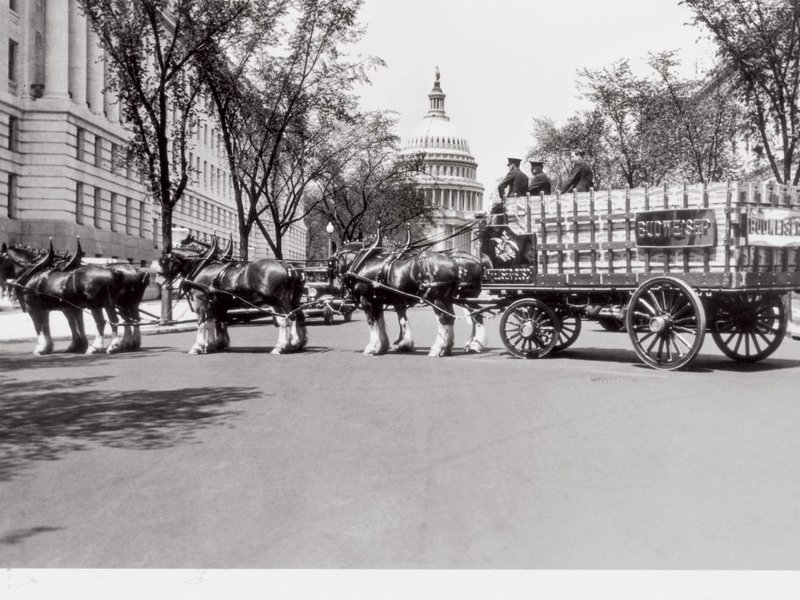

FDR signed the Cullen–Harrison Act into law on March 22, 1933, commenting “I think this would be a good time for a beer.” The law went effect on April 7, allowing Americans to buy, sell and drink beer containing up to 3.2% alcohol.

FDR signed the Cullen–Harrison Act into law on March 22, 1933, commenting “I think this would be a good time for a beer.” The law went effect on April 7, allowing Americans to buy, sell and drink beer containing up to 3.2% alcohol.

Be that at it as it may, the animal is a voracious herbivore, spending daylight hours at the bottom of rivers & lakes, happily munching on vegetation.

Be that at it as it may, the animal is a voracious herbivore, spending daylight hours at the bottom of rivers & lakes, happily munching on vegetation.

During the 2nd Boer war, the pair had sworn to kill each other. In 1910, these two men became partners in a mission to bring hippos, to America’s dinner table.

During the 2nd Boer war, the pair had sworn to kill each other. In 1910, these two men became partners in a mission to bring hippos, to America’s dinner table.

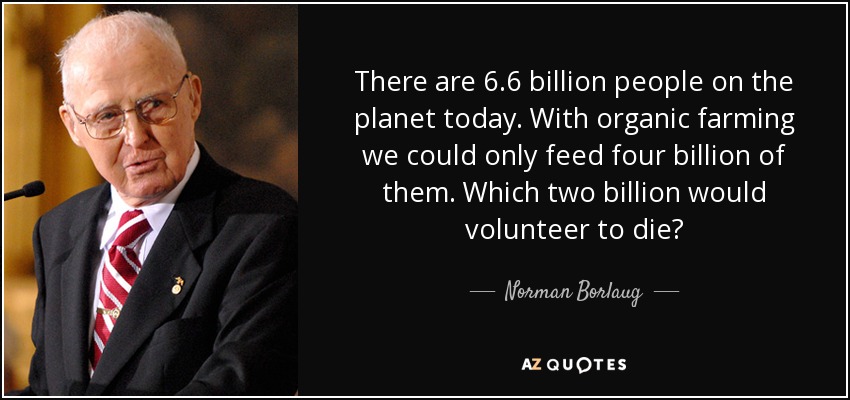

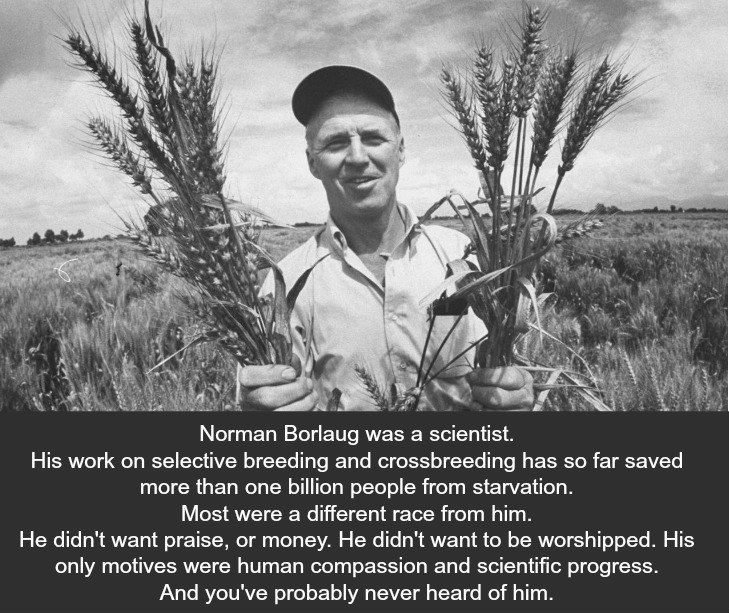

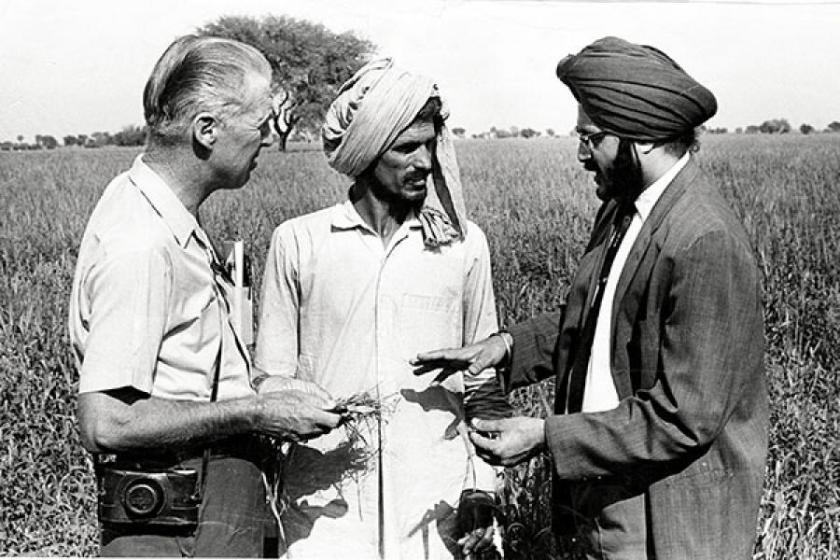

Borlaug earned his Bachelor of Science in Forestry, in 1937. Nearing the end of his undergraduate education, he attended a lecture by Professor Elvin Charles Stakman discussing plant rust disease, a parasitic fungus which feeds on phytonutrients in wheat, oats, and barley crops.

Borlaug earned his Bachelor of Science in Forestry, in 1937. Nearing the end of his undergraduate education, he attended a lecture by Professor Elvin Charles Stakman discussing plant rust disease, a parasitic fungus which feeds on phytonutrients in wheat, oats, and barley crops.

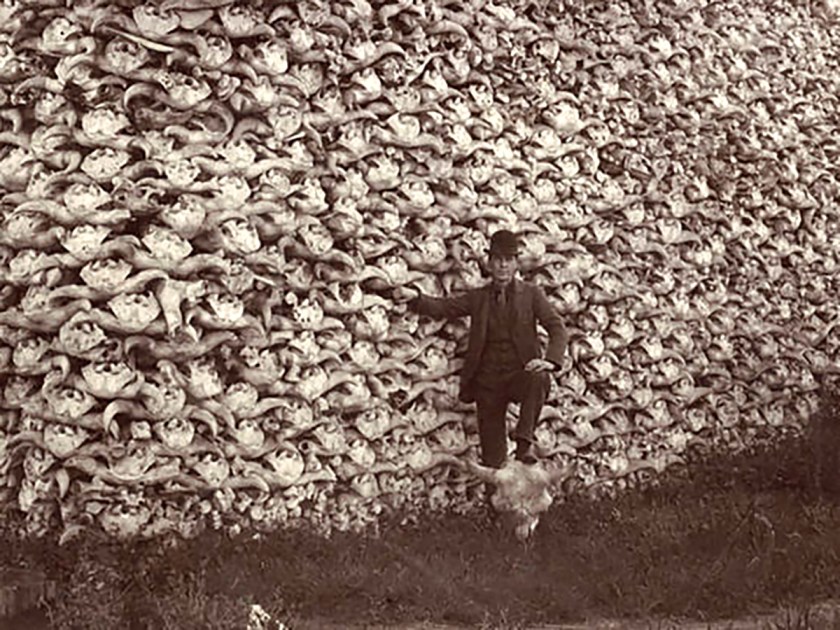

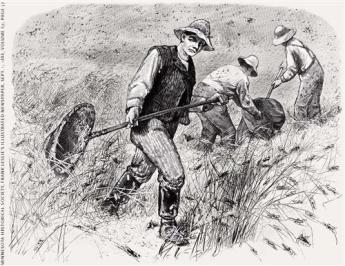

Farmers used gunpowder, fire and water, anything they could think of, to destroy what could only be seen as a plague of biblical proportion. They smeared them with “hopperdozers”, a plow-like device pulled behind horses, designed to knock jumping locusts into a pan of liquid poison or fuel, or even sucking them into vacuum cleaner-like contraptions.

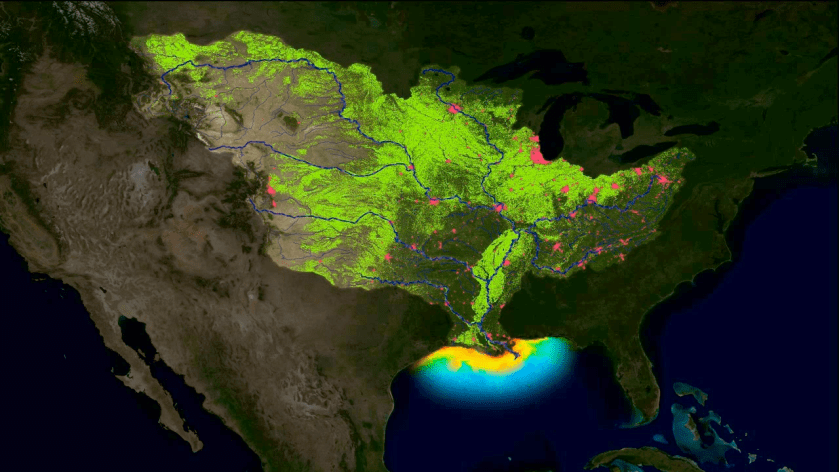

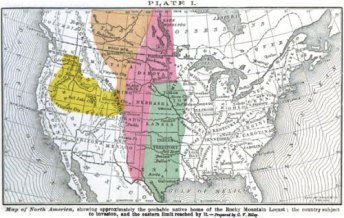

Farmers used gunpowder, fire and water, anything they could think of, to destroy what could only be seen as a plague of biblical proportion. They smeared them with “hopperdozers”, a plow-like device pulled behind horses, designed to knock jumping locusts into a pan of liquid poison or fuel, or even sucking them into vacuum cleaner-like contraptions. And then the locust went away, and no one is entirely certain, why. It is theorized that plowing, irrigation and harrowing destroyed up to 150 egg cases per square inch, in the years between swarms. Great Plains settlers, particularly those alongside the Mississippi river, appear to have disrupted the natural life cycle. Winter crops, particularly wheat, enabled farmers to “beat them to the punch”, putting away stockpiles of food before the pestilence reached the swarming phase.

And then the locust went away, and no one is entirely certain, why. It is theorized that plowing, irrigation and harrowing destroyed up to 150 egg cases per square inch, in the years between swarms. Great Plains settlers, particularly those alongside the Mississippi river, appear to have disrupted the natural life cycle. Winter crops, particularly wheat, enabled farmers to “beat them to the punch”, putting away stockpiles of food before the pestilence reached the swarming phase.

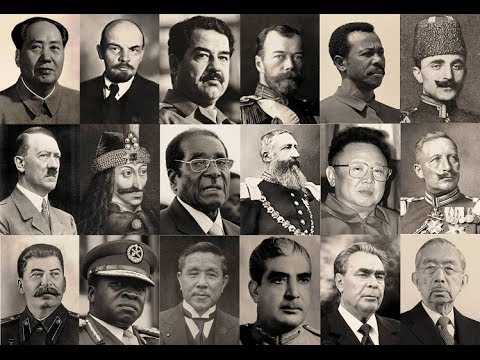

As Stalin’s Soviet Union imposed the “terror famine” of 1932-’33, the deliberate starvation of millions of Ukrainian peasant farmers known as the

As Stalin’s Soviet Union imposed the “terror famine” of 1932-’33, the deliberate starvation of millions of Ukrainian peasant farmers known as the  As director of the Soviet Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lysenko put his theories to work, with unsurprisingly dismal results. He’d force Soviet farmers to plant WAY too close together, on the theory that plants of the same “class” would “cooperate” with one another, and that “mutual assistance” takes place within and even across plant species.

As director of the Soviet Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lysenko put his theories to work, with unsurprisingly dismal results. He’d force Soviet farmers to plant WAY too close together, on the theory that plants of the same “class” would “cooperate” with one another, and that “mutual assistance” takes place within and even across plant species.

By the siege’s end in the Spring of 1944, nine of them had starved to death, standing watch over all that food. These guys had stood guard over their seed bank for twenty-eight months, without eating so much as a grain.

By the siege’s end in the Spring of 1944, nine of them had starved to death, standing watch over all that food. These guys had stood guard over their seed bank for twenty-eight months, without eating so much as a grain.

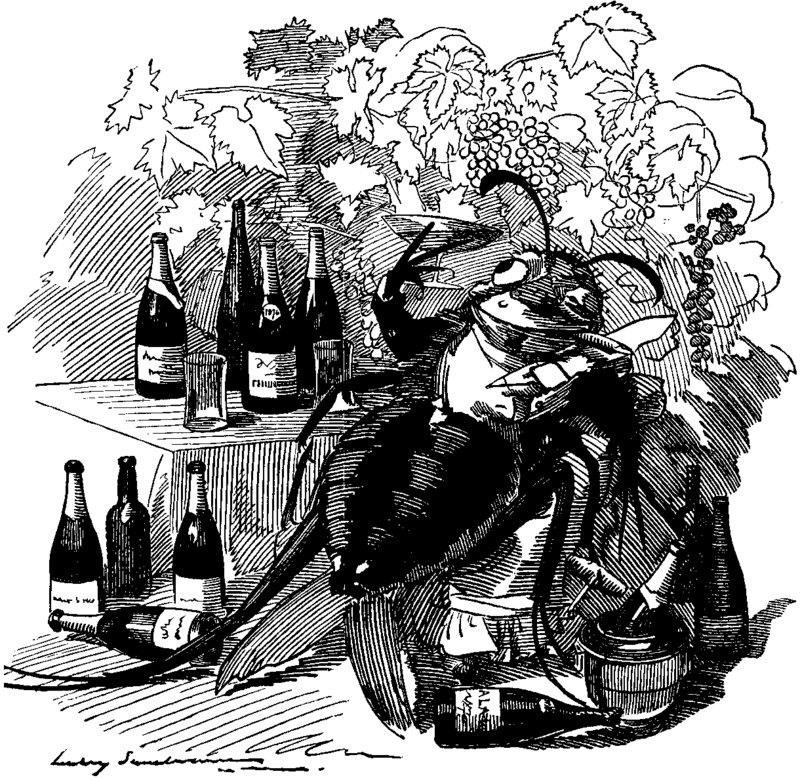

The oldest winery for which archaeological evidence exists was established around BC4100, in present-day Armenia. The Egyptian Pharoahs were producing a wine-like substance from 3100BC for use in public ceremonies, due to its resemblance to blood.

The oldest winery for which archaeological evidence exists was established around BC4100, in present-day Armenia. The Egyptian Pharoahs were producing a wine-like substance from 3100BC for use in public ceremonies, due to its resemblance to blood. Sounds like a great job, as Greek Gods go.

Sounds like a great job, as Greek Gods go.

The legions of Rome expanded the Empire across Europe from modern day France and Germany into Portugal and Spain. Everywhere the Legions went, vineyards were soon to follow. To this day, some regions are said to have more ‘Terroir’, than others.

The legions of Rome expanded the Empire across Europe from modern day France and Germany into Portugal and Spain. Everywhere the Legions went, vineyards were soon to follow. To this day, some regions are said to have more ‘Terroir’, than others.

The story is almost certainly a myth, a later embellishment to the story. During his 47 year career, Pérignon went to considerable lengths to eliminate bubbles from his wine. Dom Pérignon never succeed in that goal, yet he did make bubbly wine a whole lot better, using corks for the first time to prevent the escape of carbon dioxide, and perfecting a ‘gentle’ pressing technique which left out the murkiness of the skins.

The story is almost certainly a myth, a later embellishment to the story. During his 47 year career, Pérignon went to considerable lengths to eliminate bubbles from his wine. Dom Pérignon never succeed in that goal, yet he did make bubbly wine a whole lot better, using corks for the first time to prevent the escape of carbon dioxide, and perfecting a ‘gentle’ pressing technique which left out the murkiness of the skins. Pérignon didn’t like white grapes because of their tendency to enter refermentation. He preferred the Pinot Noir, and would aggressively prune the plants so that vines grew no higher than three feet and produced a smaller crop. The harvest was always in the cool, damp early morning hours, and Pérignon took every precaution to avoid bruising or breaking his grapes. Over-ripe and overly large fruit was always thrown out. Pérignon never permitted grapes to be trodden upon, always preferring the use of multiple presses.

Pérignon didn’t like white grapes because of their tendency to enter refermentation. He preferred the Pinot Noir, and would aggressively prune the plants so that vines grew no higher than three feet and produced a smaller crop. The harvest was always in the cool, damp early morning hours, and Pérignon took every precaution to avoid bruising or breaking his grapes. Over-ripe and overly large fruit was always thrown out. Pérignon never permitted grapes to be trodden upon, always preferring the use of multiple presses.

Often unseen in times of such dread calamity, are the humanitarian workers. Those who tend to the physical and spiritual requirements, the countless small comforts, of those so afflicted.

Often unseen in times of such dread calamity, are the humanitarian workers. Those who tend to the physical and spiritual requirements, the countless small comforts, of those so afflicted.

A small group of carefully selected female officers was sent to France on August 22. That first party comprised six men, three women and a married couple. Within fifteen months their number had expanded by a factor of 400.

A small group of carefully selected female officers was sent to France on August 22. That first party comprised six men, three women and a married couple. Within fifteen months their number had expanded by a factor of 400. ‘Hutments’ were formed all over the front, many right out at the front lines. There were canteen services. Religious observances of all denominations were held in these facilities. Concert performances were given, clothing mended and words of kindness offered in response to all manner of personal problems. On one occasion, the Loyal Order of Moose conducted a member initiation. Pies and cakes were baked in crude ovens and lemonade served to hot and thirsty troops. Of all these corporal works of mercy, the ones best remembered by the ‘doughboys’ themselves, were the doughnuts.

‘Hutments’ were formed all over the front, many right out at the front lines. There were canteen services. Religious observances of all denominations were held in these facilities. Concert performances were given, clothing mended and words of kindness offered in response to all manner of personal problems. On one occasion, the Loyal Order of Moose conducted a member initiation. Pies and cakes were baked in crude ovens and lemonade served to hot and thirsty troops. Of all these corporal works of mercy, the ones best remembered by the ‘doughboys’ themselves, were the doughnuts.

Before long, the women got better at it. Soon they were turning out 2,500 to 9,000 doughnuts a day. An elderly French blacksmith made Purviance a doughnut cutter, out of a condensed milk can and a camphor-ice tube, attached to a wooden block.

Before long, the women got better at it. Soon they were turning out 2,500 to 9,000 doughnuts a day. An elderly French blacksmith made Purviance a doughnut cutter, out of a condensed milk can and a camphor-ice tube, attached to a wooden block.

You must be logged in to post a comment.