Hannah Reitsch wanted to fly. Born March 29, 1912 into an upper-middle-class family in Hirschberg, Silesia, it’s all she ever thought about. At the age of four, she tried to jump off the family balcony, to experience flight. In her 1955 autobiography The Sky my Kingdom, Reitsch wrote: ‘The longing grew in me, grew with every bird I saw go flying across the azure summer sky, with every cloud that sailed past me on the wind, till it turned to a deep, insistent homesickness, a yearning that went with me everywhere and could never be stilled.’

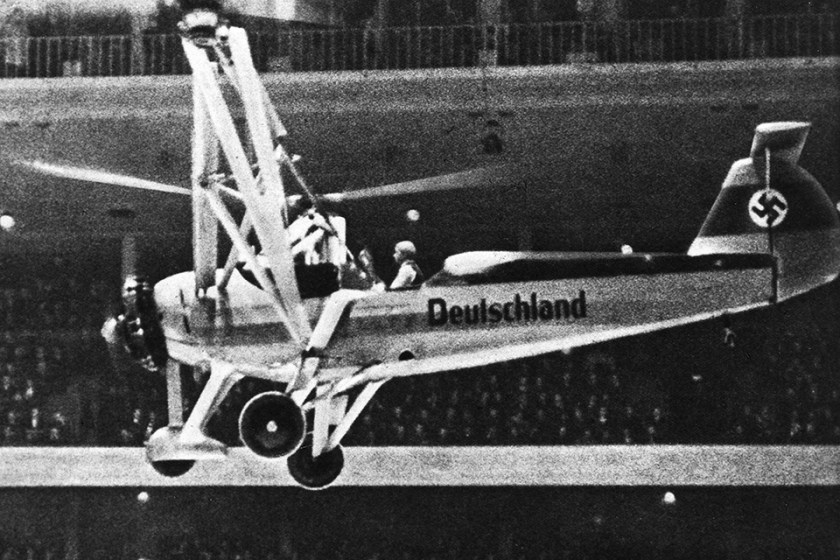

Reitsch began flying gliders in 1932, as the treaty of Versailles prohibited anyone flying “war planes” in Germany. In 1934, she broke the world’s altitude record for women (9,184 feet). In 1936, Reitsch was working on developing dive brakes for gliders, when she was awarded the honorary rank of Flugkapitän, the first woman ever so honored. In 1937 she became a Luftwaffe civilian test pilot. She would hold the position until the end of WW2.

Reitsch began flying gliders in 1932, as the treaty of Versailles prohibited anyone flying “war planes” in Germany. In 1934, she broke the world’s altitude record for women (9,184 feet). In 1936, Reitsch was working on developing dive brakes for gliders, when she was awarded the honorary rank of Flugkapitän, the first woman ever so honored. In 1937 she became a Luftwaffe civilian test pilot. She would hold the position until the end of WW2.

A German Nationalist who believed she owed her allegiance to the Fatherland more than to any party, Reitsch was patriotic and loyal, and more than a little politically naive. Her work brought her into contact with the highest levels of Nazi party officialdom. Like the victims of Soviet purges who went to their death believing that it would all stop “if only Stalin knew”, Reitsch refused to believe that Hitler had anything to do with events such as the Kristallnacht pogrom. She dismissed any talk of concentration camps, as “mere propaganda”.

As a test pilot, Reitsch won an Iron Cross, Second Class, for risking her life in an attempt to cut British barrage-balloon cables. On one test flight of the rocket powered Messerschmitt 163 Komet in 1942, she flew the thing at speeds of 500 mph, a speed nearly unheard of at the time. She spun out of control and crash-landed on her 5th flight, leaving her with severe injuries. Her nose was all but torn off, her skull fractured in four places. Two facial bones were broken, and her upper and lower jaws out of alignment. Even then, she managed to write down what had happened, before she collapsed.

Doctors did not expect her to live, let alone fly again. She spent five months in hospital, and suffered from debilitating dizzy spells. She put herself on a program of climbing trees and rooftops, to regain her sense of balance. Soon, she was test flying again.

Doctors did not expect her to live, let alone fly again. She spent five months in hospital, and suffered from debilitating dizzy spells. She put herself on a program of climbing trees and rooftops, to regain her sense of balance. Soon, she was test flying again.

On this day in 1944, Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring awarded her a special diamond-encrusted version of the Gold Medal for Military Flying. Adolf Hitler personally awarded her an Iron Cross, First Class, the first and only woman in German history, so honored.

It was while receiving this second Iron Cross in Berchtesgaden, that Reitsch suggested the creation of a Luftwaffe suicide squad, “Operation Self Sacrifice”.

Hitler was initially put off by the idea, though she finally persuaded him to look into modifying a Messerschmitt Me-328B fighter for the purpose. Reitsch put together a suicide group, becoming the first to take the pledge, though the idea would never take shape. The pledge read, in part: “I hereby voluntarily apply to be enrolled in the suicide group as a pilot of a human glider-bomb. I fully understand that employment in this capacity will entail my own death.”

Hitler was initially put off by the idea, though she finally persuaded him to look into modifying a Messerschmitt Me-328B fighter for the purpose. Reitsch put together a suicide group, becoming the first to take the pledge, though the idea would never take shape. The pledge read, in part: “I hereby voluntarily apply to be enrolled in the suicide group as a pilot of a human glider-bomb. I fully understand that employment in this capacity will entail my own death.”

The plan came to an abrupt halt when an Allied bombing raid wiped out the factory in which the prototype Me-328s were being built.

In the last days of the war, Hitler dismissed his designated successor Hermann Göring, over a telegram in which the Luftwaffe head requested permission to take control of the crumbling third Reich. Hitler appointed Generaloberst Robert Ritter von Greim, ordering Hannah to take him out of Berlin and giving each a vial of cyanide, to be used in the event of capture. The Arado Ar 96 left the improvised airstrip on the evening of April 28, under small arms fire from Soviet troops. It was the last plane to leave Berlin. Two days later, Adolf Hitler was dead.

Taken into American custody on May 9, Reitsch and von Greim repeated the same statement to American interrogators: “It was the blackest day when we could not die at our Führer’s side.” She spent 15 months in prison, giving detailed testimony as to the “complete disintegration’ of Hitler’s personality, during the last months of his life. She was found not guilty of war crimes, and released in 1946. Von Greim committed suicide, in prison.

In her 1951 memoir “Fliegen – mein leben”, (Flying is my life), Reitsch offers no moral judgement one way or the other, on Hitler or the Third Reich.

She resumed flying competitions in 1954, opening a gliding school in Ghana in 1962. She later traveled to the United States, where she met Igor Sikorsky and Neil Armstrong, and even John F. Kennedy.

Hannah Reitsch remained a controversial figure, due to her ties with the Third Reich. Shortly before her death in 1979, she responded to a description someone had written of her, as `Hitler’s girlfriend’. “I had been picked for this mission” she wrote, “because I was a pilot…I can only assume that the inventor of these accounts did not realize what the consequences would be for my life. Ever since then I have been accused of many things in connection with the Third Reich”.

Toward the end of her life, she was interviewed by the Jewish-American photo-journalist, Ron Laytner. Even then she was defiant: “And what have we now in Germany? A land of bankers and car-makers. Even our great army has gone soft. Soldiers wear beards and question orders. I am not ashamed to say I believed in National Socialism. I still wear the Iron Cross with diamonds Hitler gave me. But today in all Germany you can’t find a single person who voted Adolf Hitler into power … Many Germans feel guilty about the war. But they don’t explain the real guilt we share – that we lost“.

Toward the end of her life, she was interviewed by the Jewish-American photo-journalist, Ron Laytner. Even then she was defiant: “And what have we now in Germany? A land of bankers and car-makers. Even our great army has gone soft. Soldiers wear beards and question orders. I am not ashamed to say I believed in National Socialism. I still wear the Iron Cross with diamonds Hitler gave me. But today in all Germany you can’t find a single person who voted Adolf Hitler into power … Many Germans feel guilty about the war. But they don’t explain the real guilt we share – that we lost“.

Hannah Reitsch died in Frankfurt on August 24, 1979, of an apparent heart attack. Former British test pilot and Royal Navy officer Eric Brown received a letter from her earlier that month, in which she wrote, “It began in the bunker, there it shall end.” There was no autopsy, or at least there’s no report of one. Brown, for one, believes that after all those years, she may have finally taken that cyanide capsule.

Edwin seems to have had life-long problems with alcohol, often resulting in an inability to provide for his family. Amelia must have been a disciplined student despite it all, as she graduated with her high school class, on time, notwithstanding having attended six different schools.

Edwin seems to have had life-long problems with alcohol, often resulting in an inability to provide for his family. Amelia must have been a disciplined student despite it all, as she graduated with her high school class, on time, notwithstanding having attended six different schools.

Following the end of the official search, Earhart’s husband and promoter George Palmer Putnam financed private searches of the Phoenix Islands, Christmas (Kiritimati) Island, Fanning (Tabuaeran) Island, the Gilbert and the Marshall Islands, but no trace of the aircraft or its occupants was ever found.

Following the end of the official search, Earhart’s husband and promoter George Palmer Putnam financed private searches of the Phoenix Islands, Christmas (Kiritimati) Island, Fanning (Tabuaeran) Island, the Gilbert and the Marshall Islands, but no trace of the aircraft or its occupants was ever found.

Stranded and alone in the high Andes, meager supplies soon gave out. A few chocolate bars, assorted snacks and several bottles of wine. It was gone within days, as the survivors scoured the wreckage for crumbs. They ate leather from suitcases, tore apart seats hoping to find straw, finding nothing but inedible foam. Nothing grew at this altitude. There were no animals. There was nothing in that desolate place but metal, glass, ice and rock. And the frozen bodies of the dead.

Stranded and alone in the high Andes, meager supplies soon gave out. A few chocolate bars, assorted snacks and several bottles of wine. It was gone within days, as the survivors scoured the wreckage for crumbs. They ate leather from suitcases, tore apart seats hoping to find straw, finding nothing but inedible foam. Nothing grew at this altitude. There were no animals. There was nothing in that desolate place but metal, glass, ice and rock. And the frozen bodies of the dead.

The Juan Valdez of the coffee commercials is an “Arriero”, a man who transports goods using pack animals. Parrado and Canessa had hiked for almost two weeks when they were building a fire by a river, and spotted such a man on the other side. Sergio Catalán probably didn’t believe his eyes at first, but he shouted across the river. “Tomorrow”.

The Juan Valdez of the coffee commercials is an “Arriero”, a man who transports goods using pack animals. Parrado and Canessa had hiked for almost two weeks when they were building a fire by a river, and spotted such a man on the other side. Sergio Catalán probably didn’t believe his eyes at first, but he shouted across the river. “Tomorrow”.

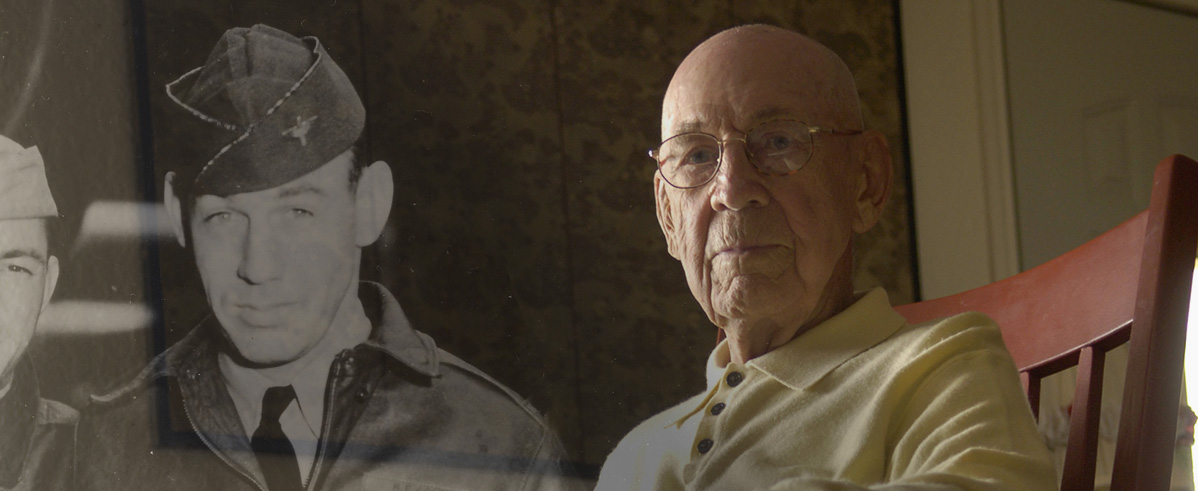

The battered aircraft was completely alone and struggling to maintain altitude, the American pilot well inside German air space, when he looked to his left and saw his worst nightmare. Three feet from his wing tip was the sleek gray shape of a German fighter, the pilot so close that the two men were looking into one another’s eyes.

The battered aircraft was completely alone and struggling to maintain altitude, the American pilot well inside German air space, when he looked to his left and saw his worst nightmare. Three feet from his wing tip was the sleek gray shape of a German fighter, the pilot so close that the two men were looking into one another’s eyes.

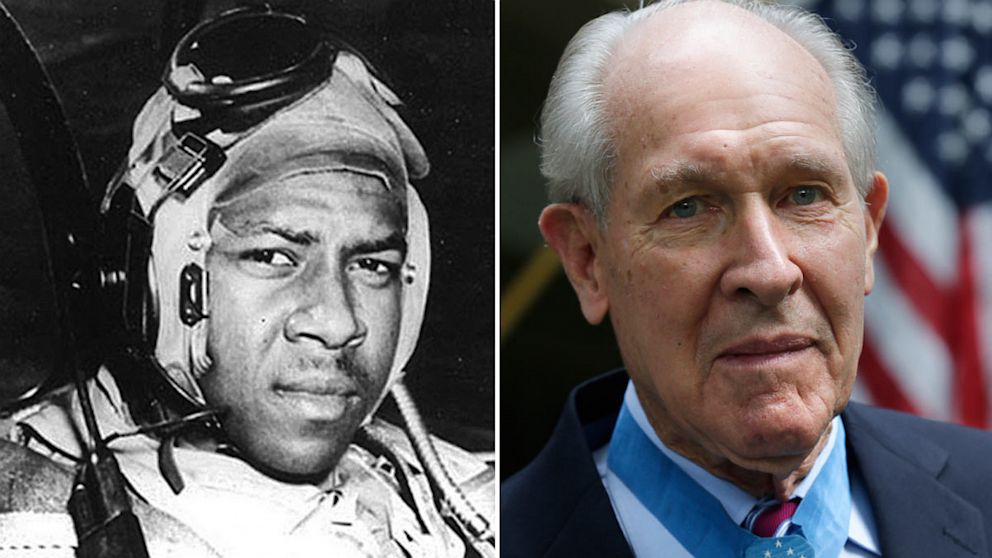

Hudner pleaded with authorities the following day to go back to the crash site, but they were unwilling to risk further loss of life. They would napalm the crash site so that the Chinese couldn’t get to the aircraft or the body, though pilots reported that it looked like the Brown’s body had already been disturbed.

Hudner pleaded with authorities the following day to go back to the crash site, but they were unwilling to risk further loss of life. They would napalm the crash site so that the Chinese couldn’t get to the aircraft or the body, though pilots reported that it looked like the Brown’s body had already been disturbed.

The diary tells of a respect this man had for “Captain Boeing”. Beaten almost senseless, his arms tied so tightly that his elbows touched behind his back, Captain Pease was driven to his knees in the last moments of his life. Knowing he was about to die, Harl Pease uttered the most searing insult possible against an expert swordsman and self-styled “samurai”. Particularly one with such a helpless victim. It was the single word, in Japanese. “Once!“.

The diary tells of a respect this man had for “Captain Boeing”. Beaten almost senseless, his arms tied so tightly that his elbows touched behind his back, Captain Pease was driven to his knees in the last moments of his life. Knowing he was about to die, Harl Pease uttered the most searing insult possible against an expert swordsman and self-styled “samurai”. Particularly one with such a helpless victim. It was the single word, in Japanese. “Once!“.

Germany needed air supremacy before “Operation Sea Lion”, the amphibious invasion of England, could begin. Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring said he would have it in four days.

Germany needed air supremacy before “Operation Sea Lion”, the amphibious invasion of England, could begin. Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring said he would have it in four days.

Czechoslovakia fell to the Nazis on the Ides of March, 1939, Czech armed forces having been ordered to offer no resistance. Some 4,000 Czech soldiers and airmen managed to get out, most escaping to neighboring Poland.

Czechoslovakia fell to the Nazis on the Ides of March, 1939, Czech armed forces having been ordered to offer no resistance. Some 4,000 Czech soldiers and airmen managed to get out, most escaping to neighboring Poland.

British military authorities were slow to recognize the flying skills of the Polskie Siły Powietrzne (Polish Air Forces), the first fighter squadrons only seeing action in the third phase of the Battle of Britain. Despite the late start, Polish flying skills proved superior to those of less-experienced Commonwealth pilots. The 303rd Polish fighter squadron became the most successful RAF fighter unit of the period, its most prolific flying ace being Czech Sergeant Josef František. He was killed in action in the last phase of the Battle of Britain, the day after his 26th birthday.

British military authorities were slow to recognize the flying skills of the Polskie Siły Powietrzne (Polish Air Forces), the first fighter squadrons only seeing action in the third phase of the Battle of Britain. Despite the late start, Polish flying skills proved superior to those of less-experienced Commonwealth pilots. The 303rd Polish fighter squadron became the most successful RAF fighter unit of the period, its most prolific flying ace being Czech Sergeant Josef František. He was killed in action in the last phase of the Battle of Britain, the day after his 26th birthday.

Bullard was assigned to the 93d Spad Squadron on August 17, 1917, flying Spad V11s and Nieuports with a mascot, a pet Rhesus Monkey he called “Jimmy”. He said, “I was treated with respect and friendship – even by those from America. Then I knew at last that there are good and bad white men just as there are good and bad black men.”

Bullard was assigned to the 93d Spad Squadron on August 17, 1917, flying Spad V11s and Nieuports with a mascot, a pet Rhesus Monkey he called “Jimmy”. He said, “I was treated with respect and friendship – even by those from America. Then I knew at last that there are good and bad white men just as there are good and bad black men.”

Kennedy and Willy remained aboard as BQ-8 completed its first remote controlled turn at 2,000′, near the North Sea coast. They removed the safety pin arming the explosive, Kennedy sending the code “Spade Flush”, to signal the task was complete. They were his last words. The aircraft exploded two minutes later, a shower of wreckage coming to earth near the village of Blythburgh in Suffolk, England. A series of small fires were started and 59 buildings were damaged, but there were no casualties on the ground. The bodies of Kennedy and Willy were never recovered.

Kennedy and Willy remained aboard as BQ-8 completed its first remote controlled turn at 2,000′, near the North Sea coast. They removed the safety pin arming the explosive, Kennedy sending the code “Spade Flush”, to signal the task was complete. They were his last words. The aircraft exploded two minutes later, a shower of wreckage coming to earth near the village of Blythburgh in Suffolk, England. A series of small fires were started and 59 buildings were damaged, but there were no casualties on the ground. The bodies of Kennedy and Willy were never recovered. When Joseph Kennedy Jr. was born, his grandfather John F. Fitzgerald, then Mayor of Boston, said, “This child is the future President of the nation”. He had been a delegate to the Democrat’s National Convention in 1940, and planned to run for Massachusetts’ 11th congressional district in 1946.

When Joseph Kennedy Jr. was born, his grandfather John F. Fitzgerald, then Mayor of Boston, said, “This child is the future President of the nation”. He had been a delegate to the Democrat’s National Convention in 1940, and planned to run for Massachusetts’ 11th congressional district in 1946.

You must be logged in to post a comment.