Itter Castle appeared in the land records of the Austrian Tyrol as early as 1240. When Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Schloss Itter was first leased and later requisitioned outright by the German government, for unspecified “Official use”.

Itter Castle appeared in the land records of the Austrian Tyrol as early as 1240. When Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Schloss Itter was first leased and later requisitioned outright by the German government, for unspecified “Official use”.

Fun Fact: Most WWII-era Nazis didn’t merely abstain from tobacco use. Nazis were rabid anti-smokers. Adolf Hitler himself once smoked two packs a day. By the start of WWII he had a standing offer of a gold watch to anyone among his inner circle who quit the habit. In 1942, Castle Itter became home to the “German Association for Combating the Dangers of Tobacco”.

By April 1943, Itter had become a prison for individuals of value to the Reich. Among them were tennis player Jean Borotra and former French Prime Ministers Édouard Daladier and Paul Reynaud. Former commanders-in-chief Maxime Weygand and Maurice Gamelin were interned there, as was Marie-Agnès Cailliau, the older sister of Charles de Gaulle. A number of Eastern Europeans were also interned at Itter, mostly employed in maintenance and other menial work around the castle.

In the early weeks of 1945, the 23rd Tank Battalion of the American 12th Armored Division fought its way across France, through Germany and into the Austrian Tyrol. 27 year-old 1st Lt. John “Jack” Lee Jr. was leading the three tank “Company B’, spearheading the drive into Kufstein and on to Munich. The unit had just fought a pitched battle at a German roadblock before clearing the town. With lead elements of the 36th Infantry moving in to take possession on May 4, Lee’s unit could finally take a rest.

By this time, Wehrmacht Major Josef Gangel and a few of his soldiers had changed sides, joining the Austrian resistance in Wörgl against roving bands of SS then in possession of the town.

Back at Itter, the last commander of the Dachau concentration camp, Eduard Weiter, had fled his command and made his way to the safety of Itter Castle. He was murdered by an unnamed SS officer on May 2, for insufficient devotion to the cause. Fearing for his own life, Itter commanding officer Sebastian Wimmer fled the Castle on May 4, followed by his guards. The now-former prisoners of Schloss Itter were alone for now, but the presence of SS units in the area made it imperative – they had to do something. While breaking into the weapons room and arming themselves with pistols, rifles, and submachine guns, Zoonimir Cuckovic, AKA “André”, purloined a bicycle and went looking for help.

André’s mad bicycle ride resulted in the one of the strangest rescues in military history. Lt. Lee tapped eight volunteers and two tanks, his own “Besotten Jenny” and Lt. Wallace Holbrook’s “Boche Buster.” Riding atop the two Shermans were six members of the all–black Company D, 17th Armored Infantry Battalion, a couple of crews from the 142nd Infantry Regiment, and the Wehrmacht’s own Josef Gangel with a Kübelwagen full of German soldiers bringing up the rear.

It was late afternoon as the convoy left for Castle Itter. Leaving Boche Buster and a few Infantry to guard the largest bridge into town. What remained of the convoy fought its way through its last SS roadblock in the early evening, roaring across the last bridge and lurching to a stop in front of Itter’s gate as night began to fall. Itter’s prisoners looked on in dismay. They had expected a column of American tanks and a heavily armed infantry force. What they had here, was a single tank with seven Americans, and a truckload of armed Germans.

It was late afternoon as the convoy left for Castle Itter. Leaving Boche Buster and a few Infantry to guard the largest bridge into town. What remained of the convoy fought its way through its last SS roadblock in the early evening, roaring across the last bridge and lurching to a stop in front of Itter’s gate as night began to fall. Itter’s prisoners looked on in dismay. They had expected a column of American tanks and a heavily armed infantry force. What they had here, was a single tank with seven Americans, and a truckload of armed Germans.

The castle’s defenders came under attack almost at once, by harrying forces sent to assess their strength and to probe the fortress for weakness. Lee ordered French prisoners to hide inside, but they refused, remaining outside and fighting alongside American and German soldiers. Frantic calls for reinforcements resulted in two more German soldiers and a teenage Austrian resistance member arriving overnight, but that would be all.

The Totenkopf, or “Death’s head” units was the SS organization responsible for  concentration camp administration for the Third Reich and some of the most fanatical soldiers of WWII. Even at this late date SS units were putting up fierce resistance across northern Austria. 100-150 of them attacked on the morning of May 5. Fighting was furious around Castle Itter, the one Sherman providing machine-gun fire support until it was destroyed by a German 88mm gun. By early afternoon Lee was able to get a desperate plea for reinforcements through to the 142nd Infantry, before being cut off. Aware that he’d been unable to give complete information on the enemy’s troop strength and disposition, Lee accepted Jean Borotra’s gallant offer of assistance.

concentration camp administration for the Third Reich and some of the most fanatical soldiers of WWII. Even at this late date SS units were putting up fierce resistance across northern Austria. 100-150 of them attacked on the morning of May 5. Fighting was furious around Castle Itter, the one Sherman providing machine-gun fire support until it was destroyed by a German 88mm gun. By early afternoon Lee was able to get a desperate plea for reinforcements through to the 142nd Infantry, before being cut off. Aware that he’d been unable to give complete information on the enemy’s troop strength and disposition, Lee accepted Jean Borotra’s gallant offer of assistance.

Literally vaulting over the castle wall, the tennis star ran through a gauntlet of SS strongpoints and ambushes to deliver his message, before donning an American uniform to help fight through to the castle’s defenders. The relief force arrived at around 4pm, as defenders were firing their last ammunition.

Literally vaulting over the castle wall, the tennis star ran through a gauntlet of SS strongpoints and ambushes to deliver his message, before donning an American uniform to help fight through to the castle’s defenders. The relief force arrived at around 4pm, as defenders were firing their last ammunition.

100 SS were captured. Lee later received the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions. Josef Gangel was killed by a sniper while trying to move Prime Minister Reynaud out of harm’s way. Today, there is a street in Wörgl which bears his name. Germany signed the unconditional surrender two days later. So ended the first and only battle in which Americans and Germans fought side by side.

Paul Reynaud didn’t like Jack Lee, remembering the American Lieutenant as “crude in both looks and manners”. “If Lee is a reflection of America’s policies”, he sniffed, “Europe is in for a hard time”. How very French of him. All that, before he got to learn the lyrics of the Horst Wessel song.

McCrae fought in one of the most horrendous battles of WWI, the second battle of Ypres, in the Flanders region of Belgium. Imperial Germany launched one of the first chemical attacks in history, attacking the Canadian position with chlorine gas on April 22, 1915. The Canadian line was broken but quickly reformed, in near-constant fighting that lasted for over two weeks.

McCrae fought in one of the most horrendous battles of WWI, the second battle of Ypres, in the Flanders region of Belgium. Imperial Germany launched one of the first chemical attacks in history, attacking the Canadian position with chlorine gas on April 22, 1915. The Canadian line was broken but quickly reformed, in near-constant fighting that lasted for over two weeks.

The vivid red flower blooming on the battlefields of Belgium, France and Gallipoli came to symbolize the staggering loss of life in that war. Since then, the red poppy has become an internationally recognized symbol of remembrance of the lives lost in all wars. I keep a red poppy pinned to my briefcase and another on the visor of my car. A reminder that no free citizen of a self-governing Republic, should ever forget where we come from. Or the prices paid by our forebears, to get us here.

The vivid red flower blooming on the battlefields of Belgium, France and Gallipoli came to symbolize the staggering loss of life in that war. Since then, the red poppy has become an internationally recognized symbol of remembrance of the lives lost in all wars. I keep a red poppy pinned to my briefcase and another on the visor of my car. A reminder that no free citizen of a self-governing Republic, should ever forget where we come from. Or the prices paid by our forebears, to get us here.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig appeared at Yankee Stadium on “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day”, July 4, 1939. He was awarded trophies and other tokens of affection by the New York sports media, fellow players and groundskeepers. He would place each one on the ground, already too weak to hold them. Addressing his fans, Gehrig described himself as “The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth”.

Gehrig appeared at Yankee Stadium on “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day”, July 4, 1939. He was awarded trophies and other tokens of affection by the New York sports media, fellow players and groundskeepers. He would place each one on the ground, already too weak to hold them. Addressing his fans, Gehrig described himself as “The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth”.

Be that as it may, the cause of death was difficult to detect, the condition of the corpse close to that of someone who had died at sea, of hypothermia and drowning. The dead man’s parents were both deceased, there were no known relatives and the man died friendless. So it was that Glyndwr Michael became the Man who Never Was.

Be that as it may, the cause of death was difficult to detect, the condition of the corpse close to that of someone who had died at sea, of hypothermia and drowning. The dead man’s parents were both deceased, there were no known relatives and the man died friendless. So it was that Glyndwr Michael became the Man who Never Was.

The non-existent Major William Martin was buried with full military honors in the Huelva cemetery of Nuestra Señora. The headstone reads:

The non-existent Major William Martin was buried with full military honors in the Huelva cemetery of Nuestra Señora. The headstone reads:

As chief of the Imperial German general staff from 1891-1905, German Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen devised the strategic roadmap by which Germany prosecuted the first world war. The “Schlieffen Plan” could be likened to a bar fight, where a fighter (Germany) had to take out one guy fast (France), before turning and facing his buddy (Imperial Russia). Of infinite importance to Schlieffen’s plan was the westward sweep through France, rolling the country into a ball on a timetable before his armies could turn east to face the “Russian Steamroller”. “When you march into France”, Schlieffen had said, “let the last man on the right brush the Channel with his sleeve.”

As chief of the Imperial German general staff from 1891-1905, German Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen devised the strategic roadmap by which Germany prosecuted the first world war. The “Schlieffen Plan” could be likened to a bar fight, where a fighter (Germany) had to take out one guy fast (France), before turning and facing his buddy (Imperial Russia). Of infinite importance to Schlieffen’s plan was the westward sweep through France, rolling the country into a ball on a timetable before his armies could turn east to face the “Russian Steamroller”. “When you march into France”, Schlieffen had said, “let the last man on the right brush the Channel with his sleeve.”

The second Battle of Ypres began with a new and terrifying weapon, on April 22, 1915. German troops placed 5,730 gas cylinders weighing 90 pounds apiece, along a four mile front. Allied troops must have looked on in wonder, as that vast yellow-green carpet crept toward their lines. Chlorine gas forms hypochlorous acid when combined with water, destroying the moist tissues of the lungs and eyes. Heavier than air, the stuff crept along the ground and poured into the trenches, forcing troops out into heavy German fire. 6,000 casualties were sustained in the gas attack alone, opening a four mile gap in the allied line. Thousands retched and coughed out their last breath, as others tossed their equipment and ran in terror.

The second Battle of Ypres began with a new and terrifying weapon, on April 22, 1915. German troops placed 5,730 gas cylinders weighing 90 pounds apiece, along a four mile front. Allied troops must have looked on in wonder, as that vast yellow-green carpet crept toward their lines. Chlorine gas forms hypochlorous acid when combined with water, destroying the moist tissues of the lungs and eyes. Heavier than air, the stuff crept along the ground and poured into the trenches, forcing troops out into heavy German fire. 6,000 casualties were sustained in the gas attack alone, opening a four mile gap in the allied line. Thousands retched and coughed out their last breath, as others tossed their equipment and ran in terror.

Richly typeset advertisements for “Music Hall Extravaganzas” include “Tickling Fritz” by the P.B.I. (Poor Bloody Infantry) Film Co. of the United Kingdom and Canada, advising the enthusiast to “Book Early”. There were Real Estate ads for property in no-man’s land. “BUILD THAT HOUSE ON HILL 60. BRIGHT-BREEZY-&-INVIGORATING. COMMANDS AN EXCELLENT VIEW OF HISTORIC TOWN OF YPRES”. Another one read “FOR SALE, THE SALIENT ESTATE – COMPLETE IN EVERY DETAIL! UNDERGROUND RESIDENCES READY FOR HABITATION. Splendid Motoring Estate! Shooting Perfect !! Fishing Good!!!”

Richly typeset advertisements for “Music Hall Extravaganzas” include “Tickling Fritz” by the P.B.I. (Poor Bloody Infantry) Film Co. of the United Kingdom and Canada, advising the enthusiast to “Book Early”. There were Real Estate ads for property in no-man’s land. “BUILD THAT HOUSE ON HILL 60. BRIGHT-BREEZY-&-INVIGORATING. COMMANDS AN EXCELLENT VIEW OF HISTORIC TOWN OF YPRES”. Another one read “FOR SALE, THE SALIENT ESTATE – COMPLETE IN EVERY DETAIL! UNDERGROUND RESIDENCES READY FOR HABITATION. Splendid Motoring Estate! Shooting Perfect !! Fishing Good!!!”

Into the gap stepped the “Old Man of the Mountain”, Hassan-i Sabbah, and his fanatically loyal, secret sect of “Nizari Ismaili” followers, the Assassins.

Into the gap stepped the “Old Man of the Mountain”, Hassan-i Sabbah, and his fanatically loyal, secret sect of “Nizari Ismaili” followers, the Assassins.

Today the Exercise Tiger disaster is largely forgotten. Some have charged official cover-up, though information from SHAEF press releases appeared in the August edition of Stars & Stripes. At least three books contain the information. It seems more likely that the immediate need for secrecy and subsequent D-Day invasion swallowed the Tiger disaster, whole. History has a way of doing that.

Today the Exercise Tiger disaster is largely forgotten. Some have charged official cover-up, though information from SHAEF press releases appeared in the August edition of Stars & Stripes. At least three books contain the information. It seems more likely that the immediate need for secrecy and subsequent D-Day invasion swallowed the Tiger disaster, whole. History has a way of doing that.

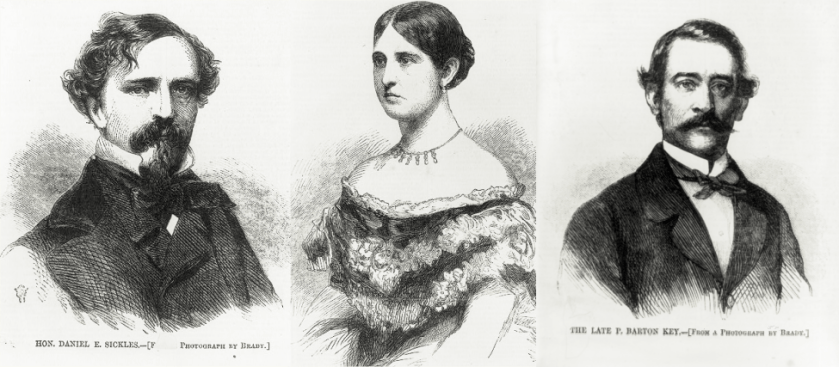

Carrying on with a known prostitute was one thing, but the Mrs. having an affair with a United States District Attorney, was quite another.

Carrying on with a known prostitute was one thing, but the Mrs. having an affair with a United States District Attorney, was quite another.

Sickles donated his leg to the newly founded Army Medical Museum in Washington, DC, along with a visiting card marked, “With the compliments of Major General D.E.S.” He visited his leg for several years thereafter, on the anniversary of the amputation.

Sickles donated his leg to the newly founded Army Medical Museum in Washington, DC, along with a visiting card marked, “With the compliments of Major General D.E.S.” He visited his leg for several years thereafter, on the anniversary of the amputation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.