As Japan emerged from the medieval period into the early modern age, the future Nippon Empire transformed from a period characterized by warring states, to the relative stability of the Tokugawa Shōgunate. Here, a feudal military government ruled from the Edo castle in the Chiyoda district of modern-day Tokyo, over some 250 provincial domains called han.

The military and governing structure of the time was based on a rigid and inflexible class system, placing the feudal lords or daimyō at the top, followed by a warrior-caste of samurai, and a lower caste of merchants and artisans. At the bottom of it all stood some 80% of the population, the peasant farmer forbidden to engage in non-agricultural work, and expected to provide the income to make the whole system work.

The military and governing structure of the time was based on a rigid and inflexible class system, placing the feudal lords or daimyō at the top, followed by a warrior-caste of samurai, and a lower caste of merchants and artisans. At the bottom of it all stood some 80% of the population, the peasant farmer forbidden to engage in non-agricultural work, and expected to provide the income to make the whole system work.

Concerned about 17th century Spanish and Portuguese colonial expansion into Asia made possible by Catholic missionaries, the Tokugawa Shōgunate issued three edicts of expulsion beginning in the early 1630s, effecting a complete ban on Christianity in the Japanese home islands. The policy ushered in a period of national seclusion, where Japanese subjects were forbidden to travel abroad, and foreign contact limited to a small number of Dutch and Chinese merchants, trading through the port of Nagasaki.

Economically, the production of fine silk and cotton fabrics, the manufacture of paper and porcelain and sake brewing operations thrived in the larger urban centers, bringing considerable wealth to the merchant class. Meanwhile, the daimyō and samurai classes remained dependent on a fixed stipend tied to agricultural production, particularly in the smaller han.

The system led to a series of peasant uprisings in the 18th and 19th centuries, and extreme dislocation within the warrior caste.

Into this world stepped the “gunboat diplomats” of President Millard Filmore in the person of Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry, determined to open the ports of Japan to trade with the west. By force, if necessary.

In time, these internal Japanese issues and the growing pressure of western encroachment led to the end of the Tokugawa period and the restoration of the Meiji Emperor, in 1868. The divisions would last, well into the 20th century.

In time, these internal Japanese issues and the growing pressure of western encroachment led to the end of the Tokugawa period and the restoration of the Meiji Emperor, in 1868. The divisions would last, well into the 20th century.

By the 1920s, two factions had evolved within the Japanese Imperial Army. The Kōdō-ha or “Imperial Way” members were the radical nationalists, resentful of civilian control over the military. This group sought a “Shōwa Restoration”, purging Japan of western ideas and returning the Emperor to what they believed to be his rightful place. By force, if necessary. Incensed by the rural poverty they blamed on the privileged classes, the group was vehemently anti-capitalist, seeking to eliminate corrupt party politics and establish a totalitarian state-socialist government, run by the military.

Opposed to this group was the much larger Tōsei-ha or “Control faction” within the army, who stressed the need for technological development within the military, while taking a more conciliatory tone with the government when it came to military spending.

In the Fall of 1930, a group of young officers of the Kōdō-ha attempted the assassinations of Prime Minister Osachi Hamaguchi, Prince Saionji Kinmochi. and Lord Privy Seal Makino Nobuaki. The group attempted a coup the following March, and the installation of soldier-stateman Ugaki Kazushige, as Premier. Ugaki himself was of the more moderate faction and took no role in the attempted coup, though he assumed responsibility and resigned his post.

That September, the ultra-nationalists launched an invasion of Manchuria, without authorization from the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office, and over objections from the civilian government. A month later the group launched another coup attempt. This too was unsuccessful but, as with the “March Incident” of six months earlier, the government’s response was excessively mild. Ringleaders were sentenced to 10 or 20 days’ house arrest, and other participants were merely transferred. For the radicals, such lenience became a virtual hall pass, ensuring that there would be future such efforts.

This “Righteous Army” faction remained influential throughout the period known as “government by assassination“, due largely to the threat that it posed. Sympathizers among the general staff and imperial family included Prince Chichibu, the Emperor’s own brother. Years later, Winston Churchill would describe Hitler’s appeasers as “one who feeds a crocodile, hoping it will eat him last”. Despite being fiercely anti-capitalist, this particular crocodile received sustenance from zaibatsu – the industrial and financial business leaders who hoped that their support would shield themselves.

General Tetsuzan Nagata was murdered in 1935, following the discovery of yet another coup plot and the Army’s arrest and subsequent expulsion of its leaders.

In 1931, Japan abandoned the gold standard in an effort to defeat deflationary forces exerted by worldwide depression. The “John Maynard Keynes of Japan”, the moderate politician and Finance Minister Takahashi Korekiyo, argued for government deficit spending to stimulate demand. The country emerged from the worst parts of the depression two years later, but Takahashi’s efforts to reign in military spending created a conspiracy mindset among more radical army officers.

On February 26, 1936, 1,438 soldiers divided into six groups attacked Prime Minister Admiral Keisuke Okada, former Prime Minister and now-Finance Minister Takahashi Korekiyo, Grand Chamberlain Admiral Suzuki Kantarō, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and former Prime Minister Saitō Makoto, the Ministry of War, the offices of the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, Tokyo police headquarters and attempted to seize the Imperial palace of the Emperor himself.

While unsuccessful, the incident killed some of Japan’s most moderate internationalist politicians, putting an end to effective civilian control over the army while increasing the military’s influence over civilian government. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the unwilling architect of the attack on Pearl Harbor, was reassigned to sea to prevent his assassination by army hard-liners. Another step had been taken, on the road to war.

Far-left anarchists mailed no fewer than 36 dynamite bombs to prominent political and business leaders in April 1919, alone. In June, another nine far more powerful bombs destroyed churches, police stations and businesses.

Far-left anarchists mailed no fewer than 36 dynamite bombs to prominent political and business leaders in April 1919, alone. In June, another nine far more powerful bombs destroyed churches, police stations and businesses. To this day there are those who describe the period as the “First Red Scare”, as a way to ridicule the concerns of the era. The criticism seems unfair. The thing about history, is that we know how their story ends. The participants don’t, any more than we know what the future holds for ourselves.

To this day there are those who describe the period as the “First Red Scare”, as a way to ridicule the concerns of the era. The criticism seems unfair. The thing about history, is that we know how their story ends. The participants don’t, any more than we know what the future holds for ourselves.

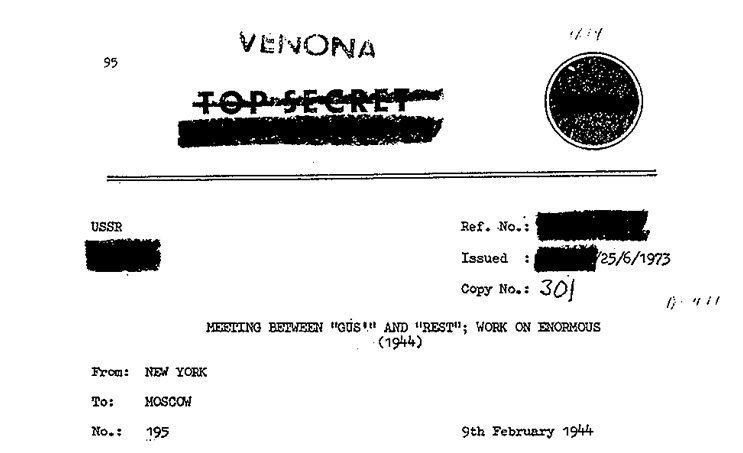

Before defecting from the Left, Chambers had secreted documents and microfilms, some of which he hid inside a pumpkin at his Maryland farm. The collection was known as the “Pumpkin Papers”, consisting of incriminating documents, written in what appeared to Hiss’ own hand, or typed on his Woodstock no. 230099 typewriter.

Before defecting from the Left, Chambers had secreted documents and microfilms, some of which he hid inside a pumpkin at his Maryland farm. The collection was known as the “Pumpkin Papers”, consisting of incriminating documents, written in what appeared to Hiss’ own hand, or typed on his Woodstock no. 230099 typewriter. Hiss’ theory never explained why Chambers side needed another typewriter, if they’d had the original long enough to mimic its imperfections with a second.

Hiss’ theory never explained why Chambers side needed another typewriter, if they’d had the original long enough to mimic its imperfections with a second.

Though Wilson didn’t mention it directly, HMS Lusitania had been torpedoed only three days earlier with the loss of 1,198, 128 of whom were Americans.

Though Wilson didn’t mention it directly, HMS Lusitania had been torpedoed only three days earlier with the loss of 1,198, 128 of whom were Americans. The reaction to the Lusitania sinking was immediate and vehement, portraying the attack as the act of barbarians and huns and demanding a German return to “prize rules”, requiring submarines to surface and search merchantmen while placing crews and passengers in “a place of safety”.

The reaction to the Lusitania sinking was immediate and vehement, portraying the attack as the act of barbarians and huns and demanding a German return to “prize rules”, requiring submarines to surface and search merchantmen while placing crews and passengers in “a place of safety”. The American cargo vessel SS Housatonic was stopped off the southwest coast of England on February 3, and boarded by German submarine U-53. Captain Thomas Ensor was interviewed by Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, who explained he was sorry, but Housatonic was “carrying food supplies to the enemy of my country”. She would be destroyed. The American Captain and crew were allowed to launch lifeboats and abandon ship, while German sailors raided the American’s soap supplies. Apparently, WWI-vintage German subs were short on soap.

The American cargo vessel SS Housatonic was stopped off the southwest coast of England on February 3, and boarded by German submarine U-53. Captain Thomas Ensor was interviewed by Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, who explained he was sorry, but Housatonic was “carrying food supplies to the enemy of my country”. She would be destroyed. The American Captain and crew were allowed to launch lifeboats and abandon ship, while German sailors raided the American’s soap supplies. Apparently, WWI-vintage German subs were short on soap. President Woodrow Wilson retaliated, breaking off diplomatic relations with Germany the following day. Three days later, a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the

President Woodrow Wilson retaliated, breaking off diplomatic relations with Germany the following day. Three days later, a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the  The contents of Zimmermann’s note were published in the American media on March 1. Even then, there was considerable antipathy toward the British side, particularly among Americans of German and Irish ethnicity. “Who says this thing is genuine, anyway”, they might have said. “Maybe it’s a British forgery”.

The contents of Zimmermann’s note were published in the American media on March 1. Even then, there was considerable antipathy toward the British side, particularly among Americans of German and Irish ethnicity. “Who says this thing is genuine, anyway”, they might have said. “Maybe it’s a British forgery”.

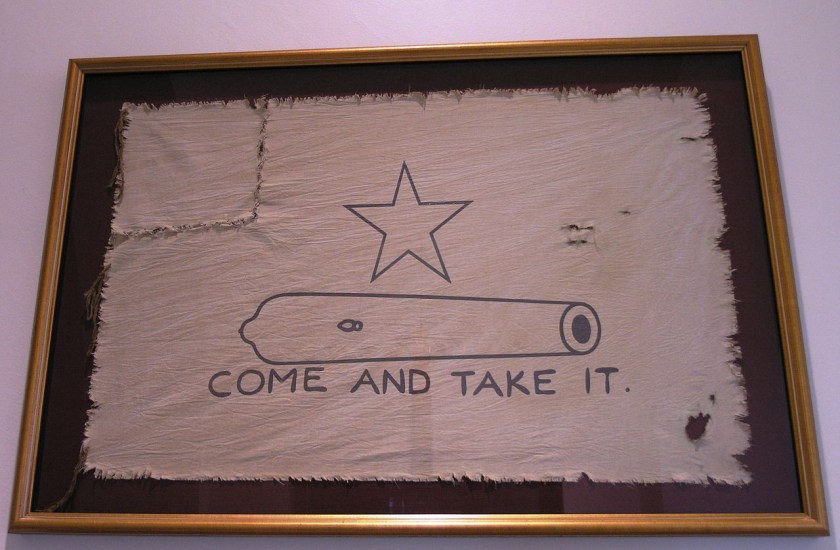

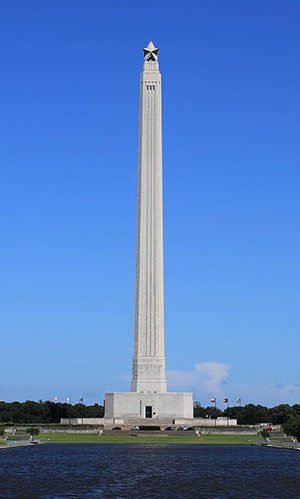

Estimates of the Alamo garrison have ranged between 189 and 257 at this stage, but current sources indicate that defenders never numbered more than 200.

Estimates of the Alamo garrison have ranged between 189 and 257 at this stage, but current sources indicate that defenders never numbered more than 200.

Eminent domain exists for a purpose, but the most extreme care should be taken in its use. Plaintiffs argued that this was not a “public use”, but rather a private corporation using the power of government to take their homes for economic development, a violation of both the takings clause of the 5th amendment and the due process clause of the 14th.

Eminent domain exists for a purpose, but the most extreme care should be taken in its use. Plaintiffs argued that this was not a “public use”, but rather a private corporation using the power of government to take their homes for economic development, a violation of both the takings clause of the 5th amendment and the due process clause of the 14th. Clarence Thomas took an originalist view, stating that the majority opinion had confused “Public Use” with “Public Purpose”. “Something has gone seriously awry with this Court’s interpretation of the Constitution“, Thomas wrote. “Though citizens are safe from the government in their homes, the homes themselves are not“. Antonin Scalia concurred, seeing any tax advantage to the municipality as secondary to the taking itself.

Clarence Thomas took an originalist view, stating that the majority opinion had confused “Public Use” with “Public Purpose”. “Something has gone seriously awry with this Court’s interpretation of the Constitution“, Thomas wrote. “Though citizens are safe from the government in their homes, the homes themselves are not“. Antonin Scalia concurred, seeing any tax advantage to the municipality as secondary to the taking itself.

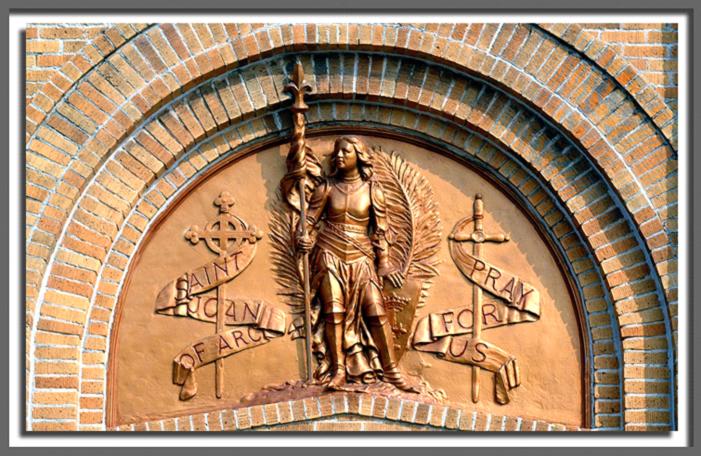

Some 70 charges were made against her by the pro-English Bishop of Beauvais, Pierre Cauchon, including witchcraft, heresy, and perjury.

Some 70 charges were made against her by the pro-English Bishop of Beauvais, Pierre Cauchon, including witchcraft, heresy, and perjury. After fifteen such interrogations her inquisitors still had nothing on her, save for the wearing of soldier’s garb, and her visions. Yet, the outcome of her “trial” was already determined. She was found guilty of heresy, and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

After fifteen such interrogations her inquisitors still had nothing on her, save for the wearing of soldier’s garb, and her visions. Yet, the outcome of her “trial” was already determined. She was found guilty of heresy, and sentenced to be burned at the stake.

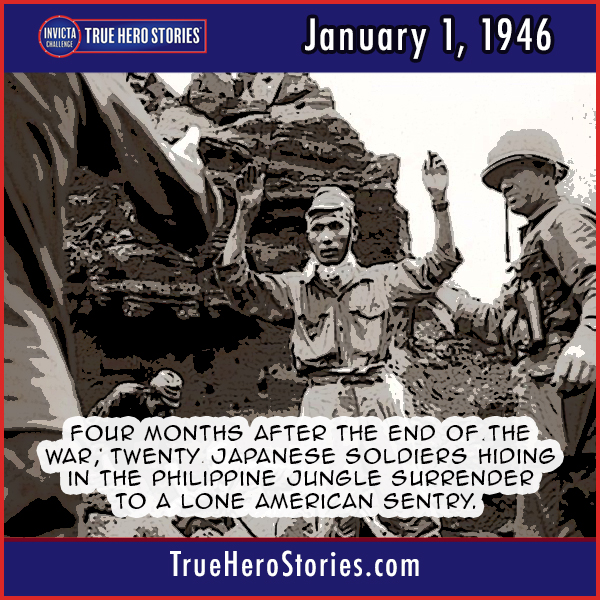

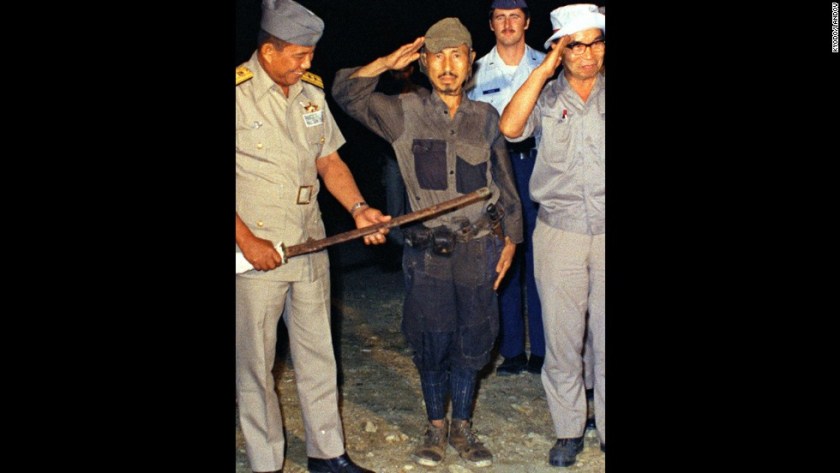

Imperial Japan would rage for another 33 years.

Imperial Japan would rage for another 33 years.

Several went on to fight for the Viet Minh against French troops in Indochina.

Several went on to fight for the Viet Minh against French troops in Indochina.

On February 7, the 71st Infantry and supporting tanks reached Ramree town where they found determined Japanese resistance, the town falling two days later. Naval forces blockaded small tributaries called “chaungs”, which the retreating Japanese used in their flight to the mainland. A Japanese air raid damaged an allied destroyer on the 11th as a flotilla of small craft crossed the strait, to rescue survivors of the garrison. By February 17, Japanese resistance had come to an end.

On February 7, the 71st Infantry and supporting tanks reached Ramree town where they found determined Japanese resistance, the town falling two days later. Naval forces blockaded small tributaries called “chaungs”, which the retreating Japanese used in their flight to the mainland. A Japanese air raid damaged an allied destroyer on the 11th as a flotilla of small craft crossed the strait, to rescue survivors of the garrison. By February 17, Japanese resistance had come to an end.

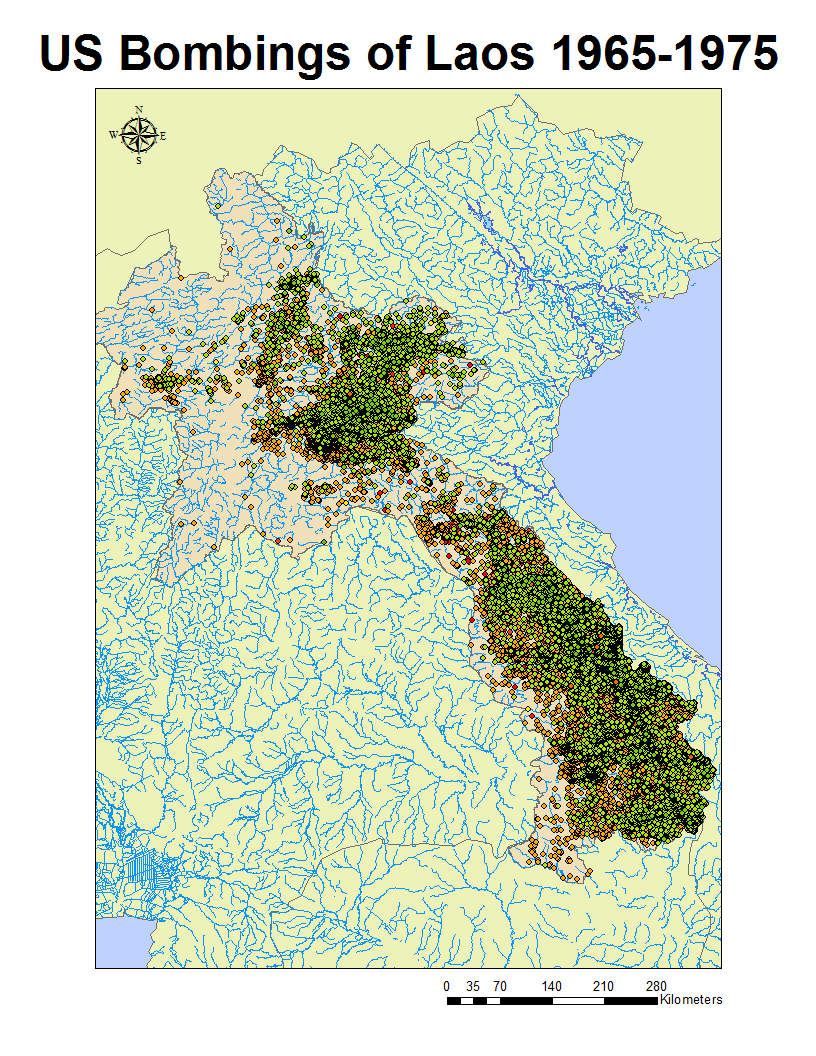

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

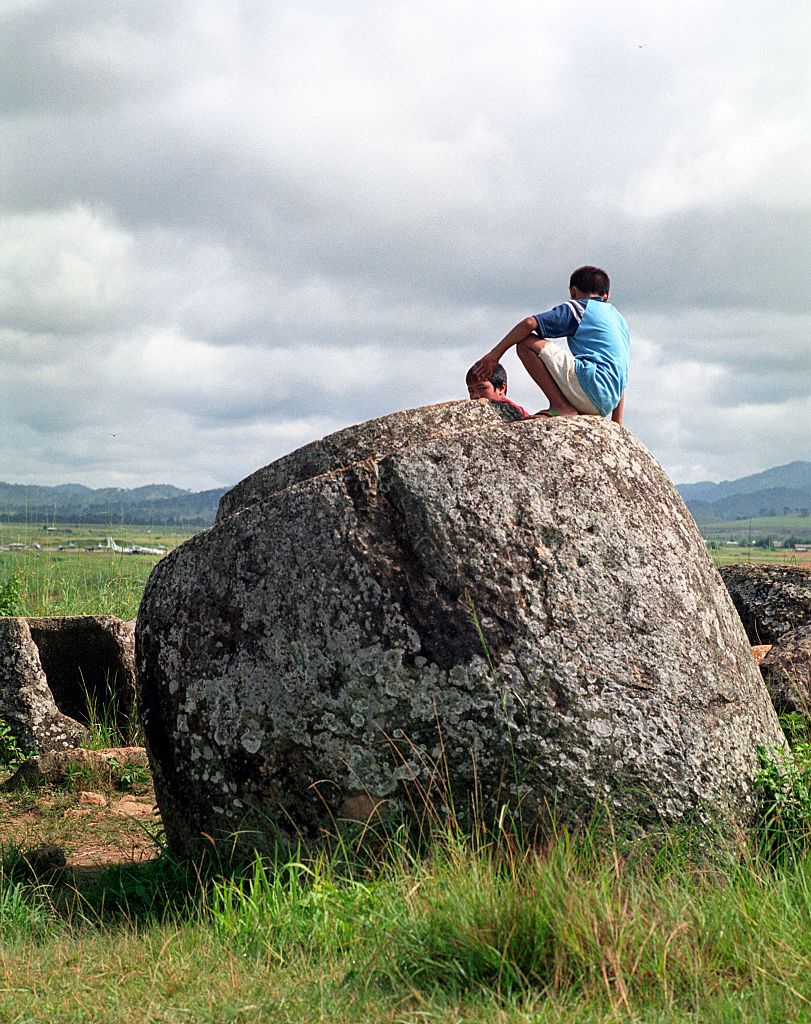

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

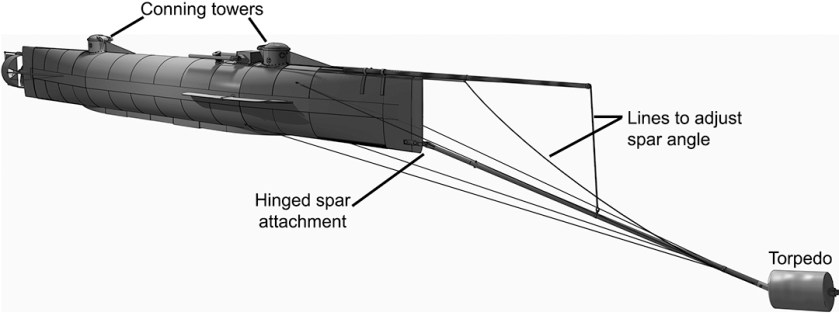

A second crew tested the submarine on October 15, this one including Horace Hunley himself. The submarine conducted a mock attack but failed to surface afterward, this time drowning all 8 crew members.

A second crew tested the submarine on October 15, this one including Horace Hunley himself. The submarine conducted a mock attack but failed to surface afterward, this time drowning all 8 crew members. Tide and current conditions in Charleston proved very different from those in Mobile. On several test runs, the torpedo floated out ahead of the sub. That wouldn’t do, so a spar was fashioned and mounted to the bow. At the end of the spar was a 137lb waterproof cask of powder, attached to a harpoon-like device with which Hunley would ram its target.

Tide and current conditions in Charleston proved very different from those in Mobile. On several test runs, the torpedo floated out ahead of the sub. That wouldn’t do, so a spar was fashioned and mounted to the bow. At the end of the spar was a 137lb waterproof cask of powder, attached to a harpoon-like device with which Hunley would ram its target.

On the coin, clearly showing signs of having been struck by a bullet, are inscribed these words:

On the coin, clearly showing signs of having been struck by a bullet, are inscribed these words:

You must be logged in to post a comment.