Nine years ago, Richard and Mayumi Heene released a helium-filled gas balloon into the atmosphere, and claimed that their six-year-old son Falcon, was stuck inside. The world looked on in horror, as a young boy soared to altitudes of 7,000-feet. National Guard helicopters and local police, gave chase. The thing flew for more than an hour, only to come down with nobody on board. Rumors quickly turned into “reports”, that an object was seen falling from the balloon. A search was carried out, but revealed nothing.

Later that day, the kid was found hiding in the attic. He’d apparently been there all day. In an interview with Wolf Blitzer for the Larry King Live television program, Falcon was asked why he’d been hiding. The boy turned to his father: “You guys said that, um, we did this for the show.” Busted. The Balloon Boy Hoax was born, for which Richard Heene was sentenced to 90 days in jail and ordered to pay $36,000, in restitution. Mayumi Heene was sentenced to 20 days in jail, to be served one weekend at a time.

Those of us of a certain age remember the “Thunder Lizard”, the Brontosaurus, that iconic dinosaur seemingly at the center of every museum display. The Sinclair Oil Company adopted the creature as its mascot. The United States Postal Service featured the animal, in a series of commemorative stamps.

Those of us of a certain age remember the “Thunder Lizard”, the Brontosaurus, that iconic dinosaur seemingly at the center of every museum display. The Sinclair Oil Company adopted the creature as its mascot. The United States Postal Service featured the animal, in a series of commemorative stamps.

Except that – oops – someone had put the wrong head on the thing and, the previously discovered ‘Apatasaurus’ was, in fact, a juvenile specimen of the same animal.

This wasn’t a ‘hoax’ so much as a mistake, forged by the great “Bone Wars”, of the 19th century. Dinosaur enthusiasts accused the Postal Service of fostering ‘scientific illiteracy’. An ironic charge, given the number of museums that had mislabeled the animal, for over a century.

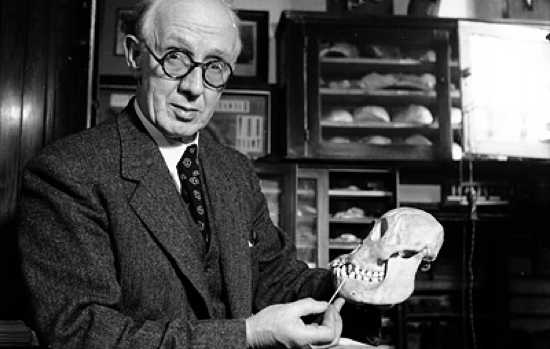

The dearly departed Brontosaurus was more a mistake, than a hoax. Not so “The Earliest Englishman”, a few fossils discovered near the village of Piltdown. Between 1911-’12, a portion of a skull was discovered along with a jawbone and a few teeth. It was the ‘missing link’ between apes and humans. Years of scientific thought would be spent, reconstructing the life and times of ‘Piltdown Man’, and fitting the creature into the narrative of our shared, evolutionary history.

In 1953, the British Museum of Natural History revealed the whole thing to have been a fabrication, a clever hoax carried out with modern bones most likely those of an orangutan, and treated with chemicals to make them appear much older.

Today we hear a lot about ‘Fake News’ but that’s nothing new. On this day in 1835, the New York Sun published the first of a six-part series, about civilization on the moon.

The “Great Moon Hoax”, ostensibly reprinted from The Edinburgh Courant, was falsely attributed to the work of Sir John Herschel, the most prominent astronomer, of his time.

The byline was that of the non-existent Dr. Andrew Grant, ostensibly a colleague of Dr. Herschel. Herschel had in fact traveled to Capetown South Africa in January 1834, to set up an observatory with a powerful new telescope.

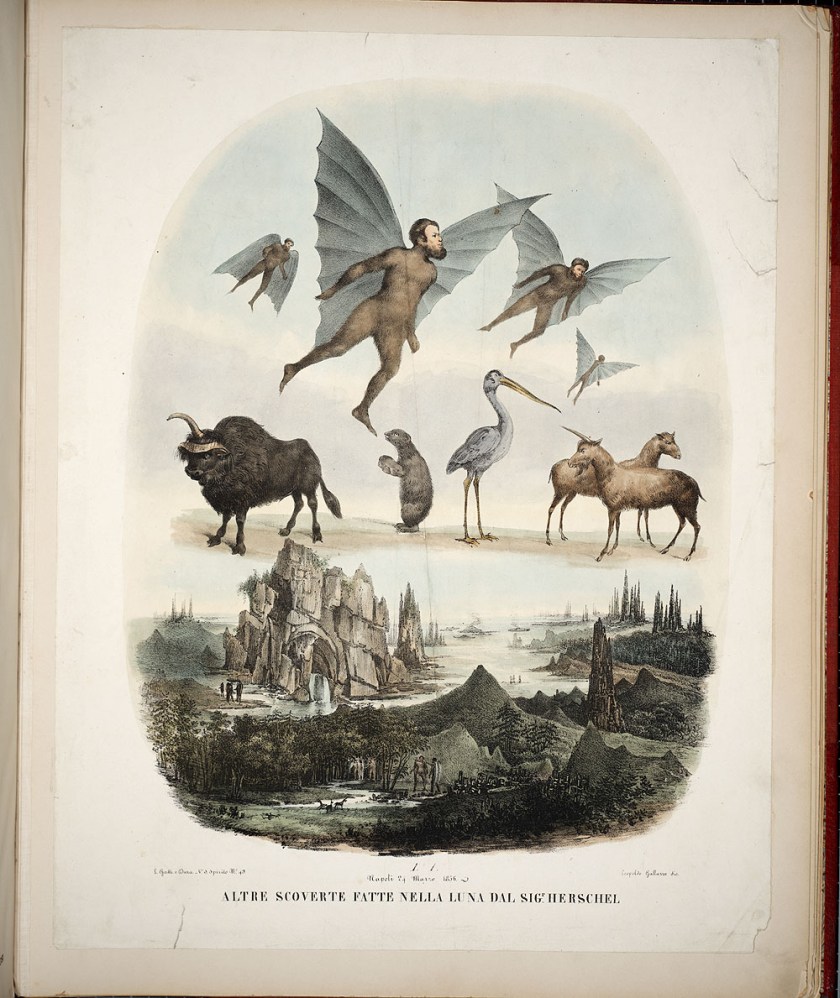

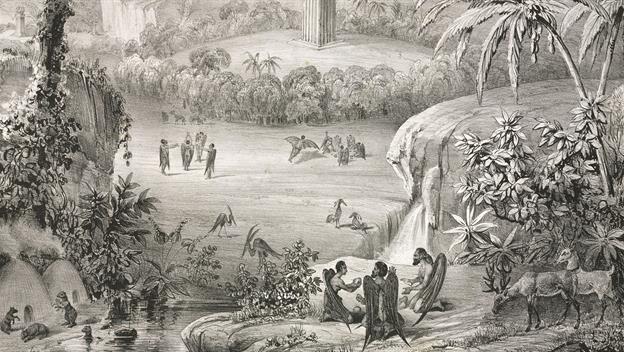

The articles took this one slender reed and ran with it, describing a 24-foot-wide behemoth instrument revealing fantastic creatures on the Moon, including bison, goats, unicorns and a two-legged creature resembling a beaver with no tail, that walked upright and carried its young in the manner of human mothers. There were temple-building, vegetarian, furry bat-like humanoids, called “Vespertilio-homo”.

The articles described palm trees and lush forests, with flowers and rushing rivers. There were valleys with melon trees, and all of it witnessed through “an immense telescope of an entirely new principle.”

Readers couldn’t get enough, and circulation figures shot up from day one. A committee of oh-so serious Yale University scientific types traveled to New York, in search of the Edinburgh Journal articles. Panicked newspaper employees sent these guys back & forth between the printing and editorial offices, hoping to wear them out. It worked. The committee returned to New Haven empty handed, never realizing they’d been punked.

That September, the Sun admitted the whole thing to have been a gag. Herschel himself knew nothing about it. The astronomer was amused, noting that nothing in his own work was quite that interesting, but would later become irritated at the incessant questions of those who took the thing seriously.

British journalist and Sun reporter Richard Adams Locke confessed to writing the series, not as a hoax, but as satire. Locke set out to ridicule some of the more outlandish astronomical theories then in publication, by the likes of Munich University professor of Astronomy Franz von Paula Gruithuisen, and his “Discovery of Many Distinct Traces of Lunar Inhabitants, Especially of One of Their Colossal Buildings.” Of course, it didn’t hurt that such a sensational tale as civilization on the moon, would help sell newspapers.

Be that as it may, readers were amused, and newspaper circulation didn’t suffer. The Sun merged with the New York World-Telegram in 1950, and folded in 1967. The New York Sun newspaper founded in 2002, has no relation to the original.

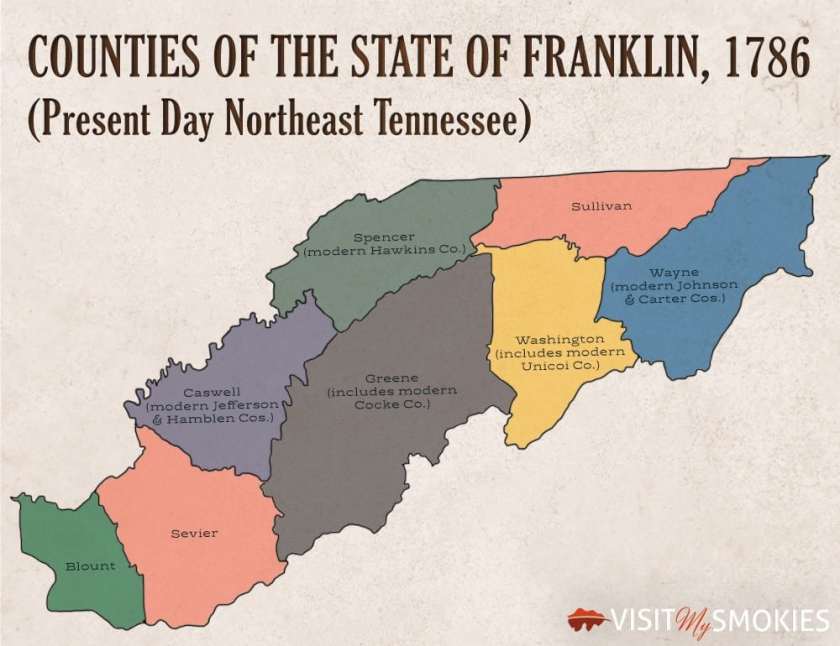

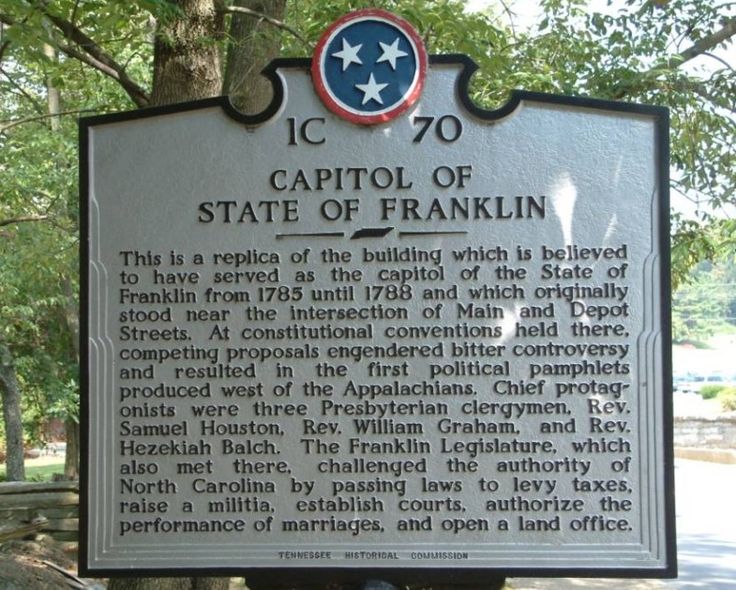

For ten years or more, settlers in the area known as the Cumberland River Valley operated their own independent government, along the western frontiers of North Carolina. With its new-found independence, settlers to the Western Counties found themselves alone in dealing with the area Cherokee, who were at that time anything but peaceful.

For ten years or more, settlers in the area known as the Cumberland River Valley operated their own independent government, along the western frontiers of North Carolina. With its new-found independence, settlers to the Western Counties found themselves alone in dealing with the area Cherokee, who were at that time anything but peaceful. The Western counties petitioned the United States Congress for statehood the following May as the 14th state in the Union, the independent state of “Frankland”. Seven states voted in the affirmative, short of the two-thirds majority required by the Articles of Confederation, for full statehood.

The Western counties petitioned the United States Congress for statehood the following May as the 14th state in the Union, the independent state of “Frankland”. Seven states voted in the affirmative, short of the two-thirds majority required by the Articles of Confederation, for full statehood.

As Franklin expanded westward, the state met resistance from the Chickamauga and “Overhill Cherokee” of war chief Dragging Canoe, a man often referred to as the “Savage Napoleon”. With the protection of neither a federal army nor a state militia, Sevier sought a loan from the Spanish government, who then attempted to assert control over the territory.

As Franklin expanded westward, the state met resistance from the Chickamauga and “Overhill Cherokee” of war chief Dragging Canoe, a man often referred to as the “Savage Napoleon”. With the protection of neither a federal army nor a state militia, Sevier sought a loan from the Spanish government, who then attempted to assert control over the territory.

Intending to deprive Confederate sympathizers from their base of support, General Thomas Ewing authorized General Order No. 11 four days later, ordering that most of four counties along the Kansas-Missouri border be depopulated. Tens of thousands of civilians were forced out of their homes as Union troops came through, burning buildings, torching fields and shooting livestock.

Intending to deprive Confederate sympathizers from their base of support, General Thomas Ewing authorized General Order No. 11 four days later, ordering that most of four counties along the Kansas-Missouri border be depopulated. Tens of thousands of civilians were forced out of their homes as Union troops came through, burning buildings, torching fields and shooting livestock.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters that day, to set a team record. The loss didn’t matter to Paul Krichell, the Yankee scout who had been following Gehrig. Krichell didn’t care about the arm either, as much as he did that powerful, left-handed bat. He had seen Gehrig hit some of the longest home runs ever seen on several Eastern campuses, including a 450′ home run at Columbia’s South Field that cleared the stands and landed at 116th Street and Broadway.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters that day, to set a team record. The loss didn’t matter to Paul Krichell, the Yankee scout who had been following Gehrig. Krichell didn’t care about the arm either, as much as he did that powerful, left-handed bat. He had seen Gehrig hit some of the longest home runs ever seen on several Eastern campuses, including a 450′ home run at Columbia’s South Field that cleared the stands and landed at 116th Street and Broadway.

The team was in Detroit on May 2 when he told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end.

The team was in Detroit on May 2 when he told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end. Gehrig left the team in June, arriving at the Mayo Clinic on the 13th. The diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) was confirmed six days later, on June 19. It was his 36th birthday. It was a cruel prognosis: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of fewer than three years.

Gehrig left the team in June, arriving at the Mayo Clinic on the 13th. The diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) was confirmed six days later, on June 19. It was his 36th birthday. It was a cruel prognosis: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of fewer than three years.

This was the world of bare knuckle boxing in the age of John L. Sullivan. He thrived in that world. The urban prize ring was his “temple of manhood”. He intended to be its Crown Prince.

This was the world of bare knuckle boxing in the age of John L. Sullivan. He thrived in that world. The urban prize ring was his “temple of manhood”. He intended to be its Crown Prince.

Sullivan’s unbeaten record over 44 professional fights came to an end on July 9, 1892, when “Gentleman Jim” Corbett unloaded a smashing left in the 21st round that put the champion down, for good. Sullivan would later say that his opponent only “gave the finishing touches to what whiskey had already done to me.”

Sullivan’s unbeaten record over 44 professional fights came to an end on July 9, 1892, when “Gentleman Jim” Corbett unloaded a smashing left in the 21st round that put the champion down, for good. Sullivan would later say that his opponent only “gave the finishing touches to what whiskey had already done to me.”

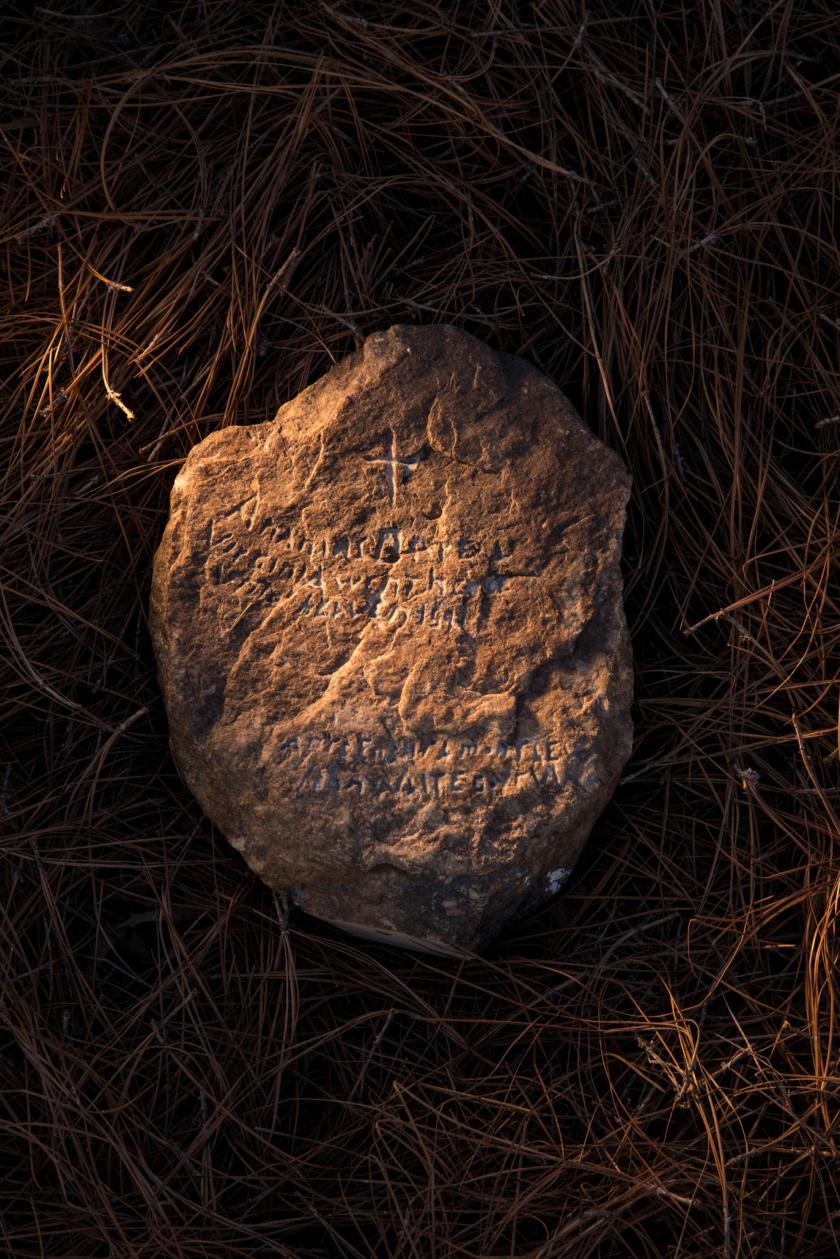

Raleigh believed that the Chesapeake afforded better opportunities for his new settlement, but Portuguese pilot Simon Fernandes, had other ideas. The caravan stopped at Roanoke Island in July, 1587, to check on the 15 men left behind a year earlier. Fernandes was a Privateer, impatient to resume his hunt for Spanish shipping. He ordered the colonists ashore on Roanoke Island.

Raleigh believed that the Chesapeake afforded better opportunities for his new settlement, but Portuguese pilot Simon Fernandes, had other ideas. The caravan stopped at Roanoke Island in July, 1587, to check on the 15 men left behind a year earlier. Fernandes was a Privateer, impatient to resume his hunt for Spanish shipping. He ordered the colonists ashore on Roanoke Island.

Research concluded at “Site X” in 2017, the cloak & dagger moniker given to deter thieves and looters. The mystery of the lost Colony of Roanoke, remains unsolved. “We don’t know exactly what we’ve got here,” admitted one archaeologist. “It remains a bit of an enigma.”

Research concluded at “Site X” in 2017, the cloak & dagger moniker given to deter thieves and looters. The mystery of the lost Colony of Roanoke, remains unsolved. “We don’t know exactly what we’ve got here,” admitted one archaeologist. “It remains a bit of an enigma.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.