At 256 tons with a barrel of 111′ 7″, the German super gun hurled 38″ shells into the city of Paris, from a range of 75 miles. If you were there in 1918, you may never have heard of the “Paris gun”. You’d have been well aware of the damage it caused. You never knew you were under attack from this thing, until the explosion. The lucky ones were those who lived to see the 4’ deep, 10’-12’ wide crater.

Parisian children made little good luck charms, as “protection” from the Paris gun. They were tiny pairs of handmade dolls, joined together by scraps of yarn. Their names were Nénette and Rintintin

Parisian children made little good luck charms, as “protection” from the Paris gun. They were tiny pairs of handmade dolls, joined together by scraps of yarn. Their names were Nénette and Rintintin

The dolls were said to provide protection for their owners, but only under certain circumstances. You couldn’t make your own and you couldn’t buy them, they had to be given to you, as a gift. They also had to remain attached, or else the little dolls would lose their protective powers.

That July, one observer noted: “It is taking a long chance in these wild days of war . . . to go about unprotected by a Nénette and Rintintin. Curious little mascot dolls they are, that have taken Paris by storm. . . . But their charm is not to be purchased. Until you have been presented with a Nénette and Rintintin, you have not their sweet protection; and if you have the one without the other, the charm is broken.”

US Army Air Service Corporal Lee Duncan was in Paris at this time, with the 135th Aero Squadron. Duncan was aware of the custom, he may even have been given such a talisman himself.

US Army Air Service Corporal Lee Duncan was in Paris at this time, with the 135th Aero Squadron. Duncan was aware of the custom, he may even have been given such a talisman himself.

In the wake of the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, Corporal Duncan was sent forward to the small village of Flirey, to check out the area’s suitability for an airfield. The village was heavily damaged by shellfire, and Duncan came upon the shattered remains of a dog pound. Once, this kennel had provided Alsatians (German Shepherd Dogs) to the Imperial German Army. Now, the only dogs left alive were a starving mother and five nursing puppies, so young that their eyes were still closed.

Corporal Duncan cared for them, selling several once the puppies were weaned. He sold the mother to an officer and three puppies to fellow airmen, keeping two for himself. Like those little yarn dolls, Duncan felt those two puppies were his good luck charms. He called them Nanette and Rin Tin Tin.

Returning home after the war, Duncan placed the dogs with a police dog breeder and trainer in Long Island. Nanette contracted pneumonia and died, the breeder giving Duncan a female puppy, “Nanette II”, to replace her.

Etzel von Oeringen was born on October 1, 1917 in Quedlinburg Germany, trained as a police dog and serving in the German Red Cross, during WW1. Left impoverished after the war and unable to support even a dog, his owner declined larger offers in preference to the most humane option, selling him to a friend in White Plains, New York.

Better known as “Strongheart”, Etzel appeared in silent films throughout the ’20s, becoming the first major canine film star and credited with enormously increasing the popularity of the breed.

Better known as “Strongheart”, Etzel appeared in silent films throughout the ’20s, becoming the first major canine film star and credited with enormously increasing the popularity of the breed.

A friend of silent film actor Eugene Pallete, Duncan became convinced that Rin Tin Tin could become the next canine movie star. “I was so excited over the motion-picture idea”, Duncan wrote, “that I found myself thinking of it night and day.”

Walking his dog on “Poverty Row”, 1920s slang for B movie studios, did the trick. Rin Tin Tin got his first film break in 1922, replacing a camera shy wolf in “The Man from Hell’s River”. His first starring role in the 1923 “Where the North Begins”, is credited with saving Warner Brothers Studios from bankruptcy.

Between-the-scenes silent film “intertitles” were easily changed from one language to another, and Rin Tin Tin films enjoyed international distribution. In 1927, Rin Tin Tin was voted Most Popular Actor by Berlin audiences.

There’s a Hollywood legend that may or may not be true, that Rin Tin Tin received the most votes for Best Actor at the 1st Academy Awards, in 1929. Inclined to take themselves oh-so seriously and wanting a human actor, the Academy threw out the ballots. German actor Emil Jannings got Best Actor on the 2nd ballot.

Rin Tin Tin appeared in 27 feature length silent films, 4 “talkies”, and countless commercials and short films. Regular programming was interrupted to announce his passing on August 10, 1932, at the age of 13.

An hour-long program about his life was broadcast the following day.

Suffering from the Great Depression like so many others, Duncan couldn’t afford a fancy funeral. By this time, he couldn’t even afford the house he lived in.

Duncan sold the house and returned the body of his beloved German Shepherd to the country of his birth, where Rin Tin Tin was buried in the Cimetière des Chiens et Autres Animaux Domestiques, in the Parisian suburb of Asnières-sur-Seine.

Duncan continued breeding the line, careful to preserve the physical qualities and intelligence of the original, while avoiding the less desirable traits that crept into other GSD bloodlines.

Duncan may have been obsessive about it, at least according to Mrs. Duncan. When she filed for divorce, she named Rin Tin Tin as co-respondent.

Rin Tin Tin and Nanette II produced at least 48 puppies.

Unique among the belligerents of WW1, the United States was the only country with no service dogs among its military forces. The next war, was a different story. The United States Armed Forces had an extensive K-9 program in WW2, when private citizens were asked to donate their dogs to the war effort.

One such dog was “Chips”, the most decorated K-9 of the war. Rin Tin Tin III, reputed to be grandson to the original but likely a more distant relation, helped to promote the program.

Rin Tin Tin was awarded his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame on February 8, 1960. Lee Duncan passed away later that same year.

At some point, Duncan had written a poem, one man’s tribute to a beloved companion animal, who was no more.

If you’ve ever loved a dog, I need not explain his final stanza.

“…A real unselfish love like yours, old pal,

Is something I shall never know again;

And I must always be a better man,

Because you loved me greatly, Rin Tin Tin”.

If you enjoyed this “Today in History”, please feel free to re-blog, “like” & share on social media, so that others may find and enjoy it too. Please click the “follow” button on the right, to receive email updates on new articles. Thank you for your interest, in the history we all share.

An unnamed British military officer felt the need to run his mouth before the Parliament, at the expense of his fellow British subjects in the American colonies. “Americans are unequal to the People of this Country”, he said, “in Devotion to Women, and in Courage, and worse than all, they are religious”.

An unnamed British military officer felt the need to run his mouth before the Parliament, at the expense of his fellow British subjects in the American colonies. “Americans are unequal to the People of this Country”, he said, “in Devotion to Women, and in Courage, and worse than all, they are religious”.

Twelve of the original thirteen states ratified these “Articles of Confederation” by February, 1779. Maryland held out for another two years, over land claims west of the Ohio River. In 1781, seven months before Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown, the 2nd Continental Congress formally ratified the Articles of Confederation. The young nation’s first governing document.

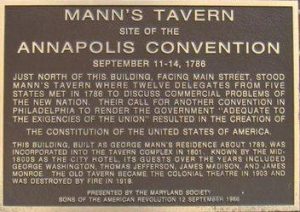

Twelve of the original thirteen states ratified these “Articles of Confederation” by February, 1779. Maryland held out for another two years, over land claims west of the Ohio River. In 1781, seven months before Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown, the 2nd Continental Congress formally ratified the Articles of Confederation. The young nation’s first governing document. The Union would probably have broken up, had not the Articles of Confederation been amended or replaced. Twelve delegates from five states met at Mann’s Tavern in Annapolis Maryland in September 1786, to discuss the issue. The decision of the Annapolis Convention was unanimous. Representatives from all the states were invited to send delegates to a constitutional convention in Philadelphia, the following May.

The Union would probably have broken up, had not the Articles of Confederation been amended or replaced. Twelve delegates from five states met at Mann’s Tavern in Annapolis Maryland in September 1786, to discuss the issue. The decision of the Annapolis Convention was unanimous. Representatives from all the states were invited to send delegates to a constitutional convention in Philadelphia, the following May. 25, 1787. The building is now known as Independence Hall, the same place where the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation were drafted.

25, 1787. The building is now known as Independence Hall, the same place where the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation were drafted.

On September 25, the first Congress adopted 12 amendments, sending them to the states for ratification.

On September 25, the first Congress adopted 12 amendments, sending them to the states for ratification.

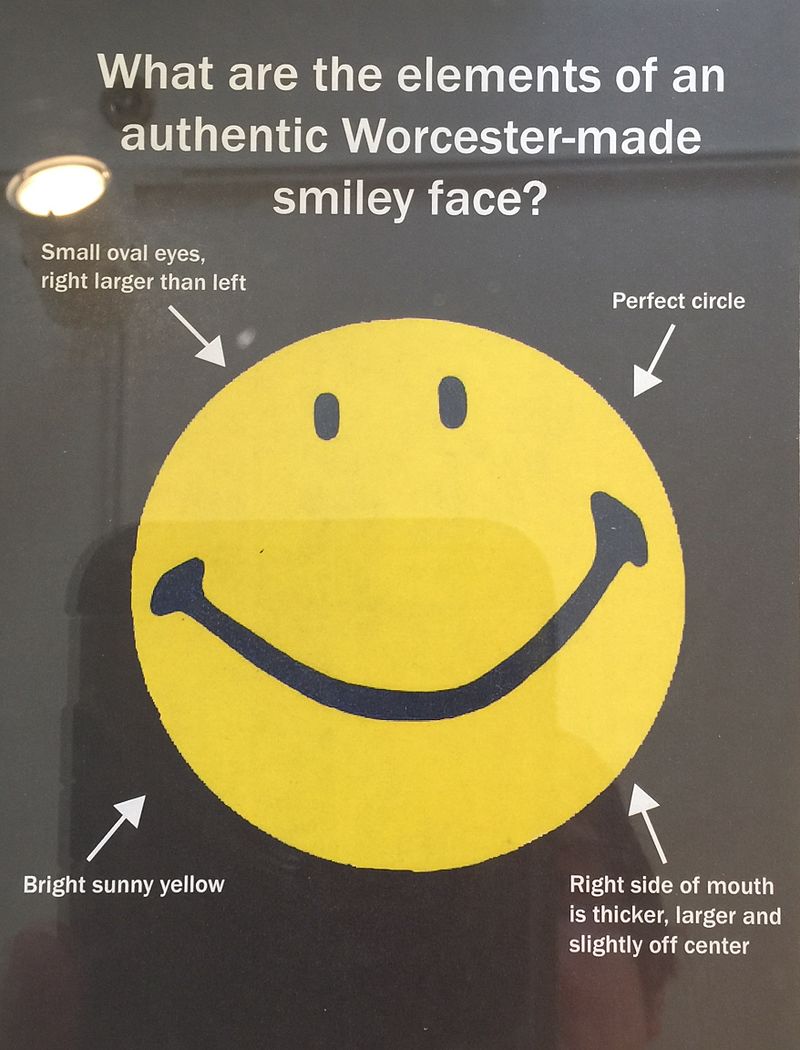

If you were to keyword search “United States Army”, “Silver Star” and “World War II”, you’ll find among a long list of recipients the name of “Ball, Harvey A. HQ, 45th Infantry Division, G.O. No. 281”.

If you were to keyword search “United States Army”, “Silver Star” and “World War II”, you’ll find among a long list of recipients the name of “Ball, Harvey A. HQ, 45th Infantry Division, G.O. No. 281”.

Those who could escape scrambled onto the deck, injured, disoriented, many still in their underwear as they emerged into the cold and darkness.

Those who could escape scrambled onto the deck, injured, disoriented, many still in their underwear as they emerged into the cold and darkness. Dorchester was listing hard to starboard and taking on water fast, with only 20 minutes to live. Port side lifeboats were inoperable due to the ship’s angle. Men jumped across the void into those on the starboard side, overcrowding them to the point of capsize. Only two of fourteen lifeboats launched successfully.

Dorchester was listing hard to starboard and taking on water fast, with only 20 minutes to live. Port side lifeboats were inoperable due to the ship’s angle. Men jumped across the void into those on the starboard side, overcrowding them to the point of capsize. Only two of fourteen lifeboats launched successfully. Rushing back to the scene, coast guard cutters found themselves in a sea of bobbing red lights, the water-activated emergency strobe lights of individual life jackets. Most marked the location of corpses. Of the 904 on board, the Coast Guard plucked 230 from the water, alive.

Rushing back to the scene, coast guard cutters found themselves in a sea of bobbing red lights, the water-activated emergency strobe lights of individual life jackets. Most marked the location of corpses. Of the 904 on board, the Coast Guard plucked 230 from the water, alive. John 15:13 says “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”. Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew when he gave away his only hope for survival, Father Washington did not ask for a Catholic. Neither minister Fox nor Poling asked for a Protestant. Each gave his life jacket to the nearest man.

John 15:13 says “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”. Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew when he gave away his only hope for survival, Father Washington did not ask for a Catholic. Neither minister Fox nor Poling asked for a Protestant. Each gave his life jacket to the nearest man.

Midway between Winter Solstice and Spring Equinox and well before the first crocus of spring has peered out across the frozen tundra, there is a moment of insanity which helps those of us living in northern climes get through to that brief, blessed moment of warmth when the mosquitoes once again have their way with us.

Midway between Winter Solstice and Spring Equinox and well before the first crocus of spring has peered out across the frozen tundra, there is a moment of insanity which helps those of us living in northern climes get through to that brief, blessed moment of warmth when the mosquitoes once again have their way with us. Groundhogs hibernate for the winter, an ability held in great envy by some people I know. During that time, their heart rate drops from 80 beats per minute to 5, and they live off their stored body fat. Another ability some of us would appreciate, very much.

Groundhogs hibernate for the winter, an ability held in great envy by some people I know. During that time, their heart rate drops from 80 beats per minute to 5, and they live off their stored body fat. Another ability some of us would appreciate, very much.

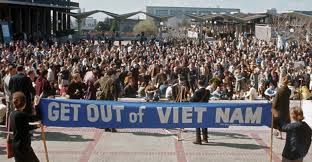

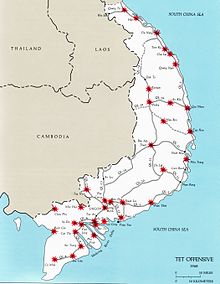

In Communist North Vietnam, the massive battlefield losses of 1966-’67 combined with the economic devastation wrought by US Aerial bombing, causing moderate factions to push for peaceful coexistence with the south. More radical factions favoring military reunification on the Indochina peninsula, needed to throw a “hail Mary” pass. Plans for a winter/spring offensive began, in early 1967. By the New Year, some 80,000 Communist fighters had quietly infiltrated the length and breadth of South Vietnam.

In Communist North Vietnam, the massive battlefield losses of 1966-’67 combined with the economic devastation wrought by US Aerial bombing, causing moderate factions to push for peaceful coexistence with the south. More radical factions favoring military reunification on the Indochina peninsula, needed to throw a “hail Mary” pass. Plans for a winter/spring offensive began, in early 1967. By the New Year, some 80,000 Communist fighters had quietly infiltrated the length and breadth of South Vietnam. Initially taken off-guard, US and South Vietnamese forces regrouped and beat back the attacks, inflicting heavy losses on North Vietnamese forces. The month-long battle for Huế (“Hway”) uncovered the massacre of as many as 6,000 South Vietnamese by Communist forces, 5-10% of the entire city. Fighting continued for over two months at the US combat base at Khe Sanh.

Initially taken off-guard, US and South Vietnamese forces regrouped and beat back the attacks, inflicting heavy losses on North Vietnamese forces. The month-long battle for Huế (“Hway”) uncovered the massacre of as many as 6,000 South Vietnamese by Communist forces, 5-10% of the entire city. Fighting continued for over two months at the US combat base at Khe Sanh.

You must be logged in to post a comment.