Isoroku Takano was born in Niigata, the son of a middle-ranked samurai of the Nagaoka Domain. His first name “Isoroku”, translating as “56”, refers to his father’s age at the birth of his son. At this time, it was common practice that samurai families without sons would “adopt” suitable young men, in order to carry on the family name, rank, and the income that came with it. The young man so adopted would carry the family name. So it was that Isoroku Takano became Isoroku Yamamoto in 1916, at the age of 32.

Isoroku Takano was born in Niigata, the son of a middle-ranked samurai of the Nagaoka Domain. His first name “Isoroku”, translating as “56”, refers to his father’s age at the birth of his son. At this time, it was common practice that samurai families without sons would “adopt” suitable young men, in order to carry on the family name, rank, and the income that came with it. The young man so adopted would carry the family name. So it was that Isoroku Takano became Isoroku Yamamoto in 1916, at the age of 32.

After graduating from the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy, Yamamoto went on to serve in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904, later returning to the Navy Staff College and emerging as Lieutenant Commander in 1916. He attended Harvard University from 1919-1921, learning fluent English. A later tour of duty in the US enabled him to travel extensively, and to study American customs and business practices.

Like most of the Japanese Navy establishment, Yamamoto promoted a strong Naval policy, at odds with the far more aggressive Army establishment. For those officers, particularly those of the Kwantung army, the Navy existed only to ferry invasion forces about the globe.

Yamamoto opposed the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the 1937 land war with

China. As Deputy Navy Minister, it was Yamamoto who apologized to Ambassador Joseph Grew, following the “accidental” bombing of the USS Panay in 1937. Even when he was the target of assassination threats by pro-war militarists, Yamamoto still opposed the attack on Pearl Harbor, which he believed would “awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve”.

Yamamoto received a steady stream of hate mail and death threats in 1938, as a growing number of army and navy officers spoke publicly against him. Irritated with Yamamoto’s immovable opposition to the tripartite pact with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, army hardliners dispatched military police to “guard” him. In one of the last acts of his short-lived administration, Navy Minister Mitsumasa Yonai reassigned Yamamoto to sea as Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet, making it harder for assassins to get at him.

Many believed that Yamamoto’s career was finished when his old adversary Hideki Tōjō ascended to the Prime Ministership in 1941. Yet there was none better to run the combined fleet. When the pro-war faction took control of the Japanese government, he bowed to the will of his superiors. It was Isoroku Yamamoto who was tasked with planning the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Many believed that Yamamoto’s career was finished when his old adversary Hideki Tōjō ascended to the Prime Ministership in 1941. Yet there was none better to run the combined fleet. When the pro-war faction took control of the Japanese government, he bowed to the will of his superiors. It was Isoroku Yamamoto who was tasked with planning the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Nothing worked against the Japanese war effort as much as time and resources. Painfully aware of the overwhelming productive capacity of the American economy, Yamamoto sought to emasculate the US High Seas fleet in the Pacific, while simultaneously striking at the oil and rubber rich resources of Southeast Asia. To accomplish this first objective, he planned to attack the anchorage at Pearl Harbor, followed by an offensive naval victory which would bring the Americans to the bargaining table. It’s not clear if he believed all that, or merely hoped that it might work out.

Yamamoto got his decisive naval engagement six months after Pearl Harbor, near Midway Island. Intended to be the second surprise that finished the carriers which had escaped destruction on December 7, American code breakers turned the tables. This time it was Japanese commanders who would be surprised.

American carrier based Torpedo bombers were slaughtered in their attack, with 36 out of 42 shot down. Yet Japanese defenses had been caught off-guard, their carriers busy rearming and refueling planes when American dive-bombers arrived.

American carrier based Torpedo bombers were slaughtered in their attack, with 36 out of 42 shot down. Yet Japanese defenses had been caught off-guard, their carriers busy rearming and refueling planes when American dive-bombers arrived.

Midway was a disaster for the Imperial Japanese navy. The carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu, the entire strength of the task force, went to the bottom. The Japanese also lost the heavy cruiser Mikuma, along with 344 aircraft and 5,000 sailors. Much has been made of the loss of Japanese aircrews at Midway, but two-thirds of them survived. The greater long term disaster, may have been the loss of all those trained aircraft mechanics and ground crew who went down with their carriers.

Midway was a disaster for the Imperial Japanese navy. The carriers Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu, the entire strength of the task force, went to the bottom. The Japanese also lost the heavy cruiser Mikuma, along with 344 aircraft and 5,000 sailors. Much has been made of the loss of Japanese aircrews at Midway, but two-thirds of them survived. The greater long term disaster, may have been the loss of all those trained aircraft mechanics and ground crew who went down with their carriers.

The Guadalcanal campaign, fought between August 1942 and February ’43, was the first major allied offensive of the Pacific war and, like Midway, a decisive victory for the allies.

Needing to boost morale after the string of defeats, Yamamoto planned an inspection  tour throughout the South Pacific. US naval intelligence intercepted and decoded his schedule. The order for “Operation Vengeance” went down the chain of command from President Roosevelt to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King to Admiral Chester Nimitz at Pearl Harbor. Sixteen Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, the only fighters capable of the ranges involved, were dispatched from Guadalcanal on April 17 with the order: “Get Yamamoto”.

tour throughout the South Pacific. US naval intelligence intercepted and decoded his schedule. The order for “Operation Vengeance” went down the chain of command from President Roosevelt to Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King to Admiral Chester Nimitz at Pearl Harbor. Sixteen Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, the only fighters capable of the ranges involved, were dispatched from Guadalcanal on April 17 with the order: “Get Yamamoto”.

Yamamoto’s two Mitsubishi G4M bombers with six Mitsubishi A6M Zeroes in escort were  intercepted over Rabaul on April 18, 1943. Knowing only that his target was “an important high value officer”, 1st Lieutenant Rex Barber opened up on the first Japanese transport until smoke billowed from its left engine. Yamamoto’s body was found in the wreckage the following day with a .50 caliber bullet wound in his shoulder, another in his head. He was dead before he hit the ground.

intercepted over Rabaul on April 18, 1943. Knowing only that his target was “an important high value officer”, 1st Lieutenant Rex Barber opened up on the first Japanese transport until smoke billowed from its left engine. Yamamoto’s body was found in the wreckage the following day with a .50 caliber bullet wound in his shoulder, another in his head. He was dead before he hit the ground.

Isoroku Yamamoto had the unenviable task of planning the attack on Pearl Harbor, but he was an unwilling participant in his own history. “In the first six to twelve months of a war with the United States and Great Britain”, he had said, “I will run wild and win victory upon victory. But then, if the war continues after that, I have no expectation of success”.

Melvin attended a year at Brooklyn College before being drafted into the Army, in WWII. After attending Army Specialized Training at VMI, Corporal Kaminsky joined the 1104th Combat Engineers Battalion, 78th Infantry Division in the European theater. There, he served through the end of the war. Most of his work was in finding and defusing explosives, though on five occasions his unit had to drop their tools and fight as Infantry.

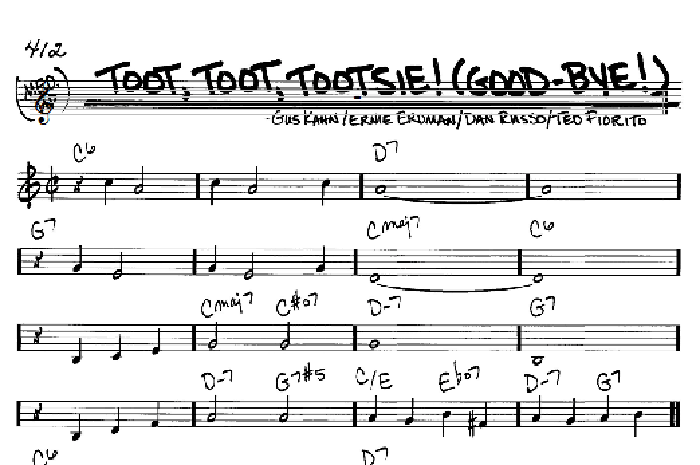

Melvin attended a year at Brooklyn College before being drafted into the Army, in WWII. After attending Army Specialized Training at VMI, Corporal Kaminsky joined the 1104th Combat Engineers Battalion, 78th Infantry Division in the European theater. There, he served through the end of the war. Most of his work was in finding and defusing explosives, though on five occasions his unit had to drop their tools and fight as Infantry. German soldiers singing a beer hall song, from the other side. Kaminsky grabbed a bullhorn and serenaded the Germans back, singing them an old tune that Al Jolson used to perform in black face, “Toot Toot Tootsie, Goodbye”. Polite applause could be heard from across the river, afterward. I can’t imagine many Allied soldiers ever tried to serenade their Nazi adversaries during World War II. The ones who actually pulled it off must number, precisely, one.

German soldiers singing a beer hall song, from the other side. Kaminsky grabbed a bullhorn and serenaded the Germans back, singing them an old tune that Al Jolson used to perform in black face, “Toot Toot Tootsie, Goodbye”. Polite applause could be heard from across the river, afterward. I can’t imagine many Allied soldiers ever tried to serenade their Nazi adversaries during World War II. The ones who actually pulled it off must number, precisely, one.

Marvin Hamlisch, Jonathan Tunick, Mike Nichols, Whoopi Goldberg, Scott Rudin, and Robert Lopez. As of this date, Brooks only needs another Oscar to be the first “Double EGOT” in history.

Marvin Hamlisch, Jonathan Tunick, Mike Nichols, Whoopi Goldberg, Scott Rudin, and Robert Lopez. As of this date, Brooks only needs another Oscar to be the first “Double EGOT” in history.

The Alaska Territory was particularly vulnerable. The Aleutian Island chain was only 750 miles from the nearest Japanese base, and there were only 12 medium bombers, 20 pursuit planes, and fewer than 22,000 troops in the entire territory. An area four times the size of Texas.

The Alaska Territory was particularly vulnerable. The Aleutian Island chain was only 750 miles from the nearest Japanese base, and there were only 12 medium bombers, 20 pursuit planes, and fewer than 22,000 troops in the entire territory. An area four times the size of Texas. equipment to Dawson Creek, the last stop on the Northern Alberta Railway. At the other end, 10,670 American troops arrived in Alaska that spring, to begin what their officers called “the biggest and hardest job since the Panama Canal.”

equipment to Dawson Creek, the last stop on the Northern Alberta Railway. At the other end, 10,670 American troops arrived in Alaska that spring, to begin what their officers called “the biggest and hardest job since the Panama Canal.” A route through the Rockies hadn’t even been identified yet.

A route through the Rockies hadn’t even been identified yet.

On October 25, Refines Sims Jr. of Philadelphia, with the all-black 97th Engineers was driving a bulldozer 20 miles east of the Alaska-Yukon line, when the trees in front of him toppled to the ground. He slammed his machine into reverse as a second bulldozer came into view, driven by Kennedy Texas Private Alfred Jalufka. North had met south, and the two men jumped off their machines, grinning. Their triumphant handshake was photographed by a fellow soldier and published in newspapers across the country, becoming an unintended first step toward desegregating the US military.

On October 25, Refines Sims Jr. of Philadelphia, with the all-black 97th Engineers was driving a bulldozer 20 miles east of the Alaska-Yukon line, when the trees in front of him toppled to the ground. He slammed his machine into reverse as a second bulldozer came into view, driven by Kennedy Texas Private Alfred Jalufka. North had met south, and the two men jumped off their machines, grinning. Their triumphant handshake was photographed by a fellow soldier and published in newspapers across the country, becoming an unintended first step toward desegregating the US military.

As a test pilot, Reitsch won an Iron Cross, Second Class, for risking her life trying to cut British barrage-balloon cables. On one test flight of the rocket powered Messerschmitt 163 Komet in 1942, she flew the thing at speeds of 500 mph, a speed nearly unheard of at the time. She spun out of control and crash-landed on her 5th flight, leaving her with severe injuries. Her nose was all but torn off, her skull fractured in four places. Two facial bones were broken, and her upper and lower jaws out of alignment. Even then, she managed to write down what had happened before passing out.

As a test pilot, Reitsch won an Iron Cross, Second Class, for risking her life trying to cut British barrage-balloon cables. On one test flight of the rocket powered Messerschmitt 163 Komet in 1942, she flew the thing at speeds of 500 mph, a speed nearly unheard of at the time. She spun out of control and crash-landed on her 5th flight, leaving her with severe injuries. Her nose was all but torn off, her skull fractured in four places. Two facial bones were broken, and her upper and lower jaws out of alignment. Even then, she managed to write down what had happened before passing out. Gold Medal for Military Flying on this day in 1944. Adolf Hitler personally awarded her an Iron Cross, First Class.

Gold Medal for Military Flying on this day in 1944. Adolf Hitler personally awarded her an Iron Cross, First Class.

Atlantic. On the 25th the Polish-British Common Defense Pact was added to the Franco-Polish Military Alliance. Should Poland be invaded by a foreign power, England and France were now committed to intervene.

Atlantic. On the 25th the Polish-British Common Defense Pact was added to the Franco-Polish Military Alliance. Should Poland be invaded by a foreign power, England and France were now committed to intervene.

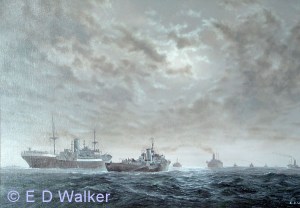

ship encounters unfolding across a theater thousands of miles wide. According to

ship encounters unfolding across a theater thousands of miles wide. According to

Norway, for repairs after running aground in the Kiel Canal. The sub was able to clear the island of Fedje off the Norway coast undetected on February 6. By this time British MI6 had broken the German Enigma code. They were well aware of Operation Caesar.

Norway, for repairs after running aground in the Kiel Canal. The sub was able to clear the island of Fedje off the Norway coast undetected on February 6. By this time British MI6 had broken the German Enigma code. They were well aware of Operation Caesar. A four dimensional firing solution accounting for time, distance, bearing and target depth was theoretically possible, but had rarely been attempted under combat conditions. Plus, there were unknown factors which could only be approximated.

A four dimensional firing solution accounting for time, distance, bearing and target depth was theoretically possible, but had rarely been attempted under combat conditions. Plus, there were unknown factors which could only be approximated.

The Troop Transport USAT Dorchester sailed out of New York Harbor on January 23, 1943, carrying 902 service members, merchant seamen and civilian workers. They were headed for the Army Command Base in southern Greenland, part of a six-ship convoy designated SG-19, together with two merchant ships and escorted by the Coast Guard Cutters Comanche, Escanaba and Tampa.

The Troop Transport USAT Dorchester sailed out of New York Harbor on January 23, 1943, carrying 902 service members, merchant seamen and civilian workers. They were headed for the Army Command Base in southern Greenland, part of a six-ship convoy designated SG-19, together with two merchant ships and escorted by the Coast Guard Cutters Comanche, Escanaba and Tampa.

more were killed in the blast, or in the clouds of steam and ammonia vapor pouring from ruptured boilers. Suddenly pitched into darkness, untold numbers were trapped below decks. With boiler power lost, there was no longer enough steam to blow the full 6 whistle signal to abandon ship, while loss of power prevented a radio distress signal. For whatever reason, there never were any signal flares.

more were killed in the blast, or in the clouds of steam and ammonia vapor pouring from ruptured boilers. Suddenly pitched into darkness, untold numbers were trapped below decks. With boiler power lost, there was no longer enough steam to blow the full 6 whistle signal to abandon ship, while loss of power prevented a radio distress signal. For whatever reason, there never were any signal flares. Private William Bednar found himself floating in 34° water, surrounded by dead bodies and debris. “I could hear men crying, pleading, praying,” he recalled. “I could also hear the chaplains preaching courage. Their voices were the only thing that kept me going.”

Private William Bednar found himself floating in 34° water, surrounded by dead bodies and debris. “I could hear men crying, pleading, praying,” he recalled. “I could also hear the chaplains preaching courage. Their voices were the only thing that kept me going.” The United States Congress attempted to confer the Medal of Honor on the four chaplains for their selfless act of courage, but strict requirements for “heroism under fire” prevented them from doing so. Congress authorized a one time, posthumous “Chaplain’s Medal for Heroism”, awarded to the next of kin by Secretary of the Army Wilber M. Brucker at Fort Myer, Virginia on January 18, 1961.

The United States Congress attempted to confer the Medal of Honor on the four chaplains for their selfless act of courage, but strict requirements for “heroism under fire” prevented them from doing so. Congress authorized a one time, posthumous “Chaplain’s Medal for Heroism”, awarded to the next of kin by Secretary of the Army Wilber M. Brucker at Fort Myer, Virginia on January 18, 1961.

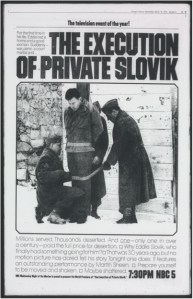

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik was paroled in 1942, his criminal record making him 4F. “Registrant not acceptable for military service”. He took a job at the Montella Plumbing and Heating company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he met bookkeeper Antoinette Wisniewski, the woman who would later become his wife.

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik was paroled in 1942, his criminal record making him 4F. “Registrant not acceptable for military service”. He took a job at the Montella Plumbing and Heating company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he met bookkeeper Antoinette Wisniewski, the woman who would later become his wife. of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan ordered the repatriation of Slovik’s remains. He was re-interred at Detroit’s Woodmere Cemetery next to Antoinette, who had gone to her final rest eight years earlier.

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan ordered the repatriation of Slovik’s remains. He was re-interred at Detroit’s Woodmere Cemetery next to Antoinette, who had gone to her final rest eight years earlier.

1942 was a bad year for the allied war in the Pacific. The Battle of Bataan alone resulted in 72,000 prisoners being taken by the Japanese, marched off to POW camps designed for 10,000 to 25,000.

1942 was a bad year for the allied war in the Pacific. The Battle of Bataan alone resulted in 72,000 prisoners being taken by the Japanese, marched off to POW camps designed for 10,000 to 25,000.

Joining the 3rd Infantry Division of George S. Patton’s 7th Army, Murphy participated in amphibious landings in Sicily in July, fighting in nearly every aspect of the Italian campaign. From Palermo to Messina and on to Naples, Anzio and Rome, the Germans were driven out of the Italian peninsula in savage and near continuous fighting that killed a member of my own family. By mid-December, the 3rd ID suffered 683 dead, 170 missing, and 2,412 wounded. Now Sergeant Murphy was there for most of it, excepting two periods when he was down with malaria.

Joining the 3rd Infantry Division of George S. Patton’s 7th Army, Murphy participated in amphibious landings in Sicily in July, fighting in nearly every aspect of the Italian campaign. From Palermo to Messina and on to Naples, Anzio and Rome, the Germans were driven out of the Italian peninsula in savage and near continuous fighting that killed a member of my own family. By mid-December, the 3rd ID suffered 683 dead, 170 missing, and 2,412 wounded. Now Sergeant Murphy was there for most of it, excepting two periods when he was down with malaria. “Colmar Pocket” was an 850 square mile area held by German troops: Murphy described it as “a huge and dangerous bridgehead thrusting west of the Rhine like an iron fist. Fed with men and materiel from across the river, it is a constant threat to our right flank; and potentially it is a perfect springboard from which the enemy could start a powerful counterattack.”

“Colmar Pocket” was an 850 square mile area held by German troops: Murphy described it as “a huge and dangerous bridgehead thrusting west of the Rhine like an iron fist. Fed with men and materiel from across the river, it is a constant threat to our right flank; and potentially it is a perfect springboard from which the enemy could start a powerful counterattack.” Let Murphy’s Medal of Honor Citation describe what happened next: “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”.

Let Murphy’s Medal of Honor Citation describe what happened next: “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”. Hollywood and, until his death in a plane crash in 1971, his post-war life was never free of it.

Hollywood and, until his death in a plane crash in 1971, his post-war life was never free of it.

were pulled on May 28, 1941, while the liner was at Saint Thomas in the US Virgin Islands. The ship had been called into service by the United States Navy, and ordered to return to Newport News.

were pulled on May 28, 1941, while the liner was at Saint Thomas in the US Virgin Islands. The ship had been called into service by the United States Navy, and ordered to return to Newport News. During her service to the United States Navy, West Point was awarded the American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and World War II Victory Medal.

During her service to the United States Navy, West Point was awarded the American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and World War II Victory Medal. adrift in foul seas, running aground in the Canary Islands the following day.

adrift in foul seas, running aground in the Canary Islands the following day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.