The largest amphibious assault in history began seventy-four years ago today, on the northern coast of France. British and Canadian forces came ashore at beaches code-named Gold, Juno and Sword. Americans faced light opposition at Utah Beach, while heavy resistance at Omaha Beach resulted in over 2,000 American casualties.

By end of day, some 156,000 Allied troops had successfully stormed the beaches of Normandy. Within a week that number had risen to 326,000 troops, over 50,000 vehicles and more than 100,000 tons of equipment.

The first phase of Operation Overlord, code named ‘Neptune’, achieved its stunning success as the result of lessons learned from the largest amphibious training exercise of WW2, the six phases of “Operation Fabius”, itself following the unmitigated disaster of a training exercise that killed more Americans, than the actual landing at Utah beach.

Slapton is a village and civil parish in the River Meadows of Devon County, where the southwest coast of England meets the English Channel. Archaeological evidence suggests human habitation from at least the bronze age. The “Domesday Book”, the recorded manuscript of the “Great Survey” of England and Wales completed in 1086 by order of William the Conqueror, names the place as “Sladone”, with a population of 200.

In late 1943, the place was home to 750 families, some of whom had never so much as left their village. Some 3,000 locals were evacuated with their livestock to make way for “Operation Tiger”, a full-scale rehearsal for the landing scheduled for the following spring.

Thousands of US military personnel were moved into the region during the winter of 1943-’44. The area was mined and bounded with barbed wire, and patrolled by sentries. Secrecy was so tight, that even those in surrounding villages, had no idea of what was happening.

Exercise Tiger was scheduled to begin on April 22, covering all aspects of the “Force U” landing on Utah beach and culminating in a live-fire beach landing at Slapton Sands at first light on April 27.

Nine large tank landing ships (LSTs) shoved off with 30,000 troops on the evening of the 26th, simulating the overnight channel crossing. Live ammunition was used in the exercise, to harden troops off to the sights, sounds and smells of actual battle. Naval bombardment was to commence 50 minutes before H-Hour, however delays resulted in landing forces coming under direct naval bombardment. An unknown number were killed in this “friendly fire” incident. Fleet rumors put the number as high as 450.

Two Royal Navy Corvettes, HMS Azalea and Scimitar, were to guard the exercise from German “Schnellboots” (what the Allies called “E-Boats”), the fast-attack craft based out of Cherbourg.

HMS Scimitar withdrew for repairs following a collision with an LST on the 27th. In the early morning darkness of the following day, the single corvette was leading 8 LSTs carrying vehicles and combat engineers of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade through Lyme Bay, when the convoy was spotted by a nine vessel S-Boat patrol.

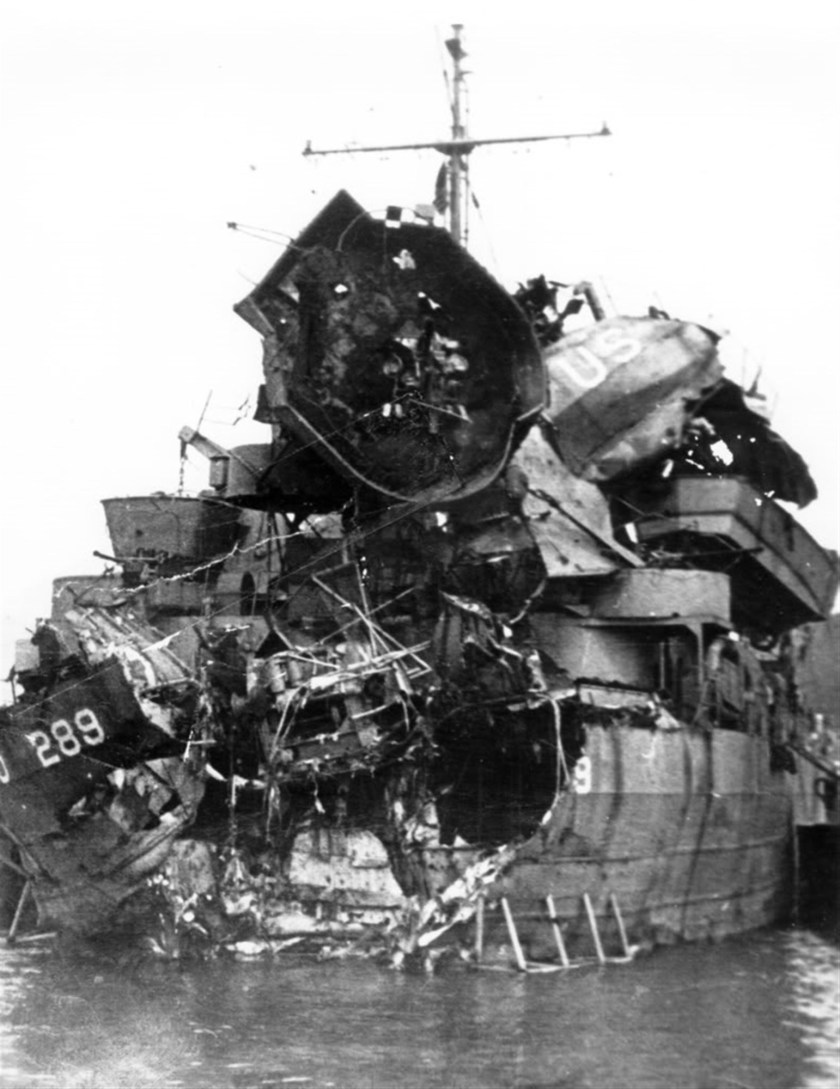

8 LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) in single-file didn’t have a chance against fast-attack craft capable of 55mph. LST-531 was torpedoed and sunk in minutes, killing 424 Army and Navy personnel. LST-507 suffered the same fate, with the loss of 202. LST-289 was severely damaged and grounded in flames, with the loss of 123. LST-511 was damaged in yet another friendly fire incident. Unable to wear their lifebelts correctly due to the large backpacks they wore, many men placed them around their waists. That only turned them upside down and that’s how they drowned, thrashing in the water with their legs above the waves. Dale Rodman, who survived the sinking of LST-507, said “The worst memory I have is setting off in the lifeboat away from the sinking ship and watching bodies float by.”

Survivors were sworn to secrecy due to official embarrassment, and the possibility of revealing the real invasion, scheduled for June. Ten officers with high level clearance were killed in the incident, but no one knew that for sure until their bodies were recovered. The D-Day invasion was nearly called off, because any of them could have been captured alive, revealing secrets during German interrogation and torture.

There remains a surprising amount of confusion, concerning the final death toll. Estimates range from 639 to 946, nearly five times the number killed in the actual Utah Beach landing. Some or all of the personnel from that damaged LST may have been aboard the other 8 on the 28th, and log books went down along with everything else. Many of the remains were never found.

The number of dead would surely have been higher, had not Captain John Doyle disobeyed orders and turned his LST-515 around, plucking 134 men from the frigid water.

Today, the Exercise Tiger disaster is mostly forgotten. Some have charged official cover-up, though information from SHAEF press releases appeared in the August edition of Stars & Stripes. At least three books describe the event. It seems more likely that the immediate need for secrecy and subsequent D-Day invasion swallowed the Tiger disaster, whole. History has a way of doing that.

Some of Slapton’s residents came home to rebuild their lives after the war, but many never returned. In the early ’70s, Devon resident and civilian Ken Small discovered an artifact of the Tiger exercise, while beachcombing on Slapton Sands. With little to no help from either the American or British governments, Small purchased rights from the American Government to a submerged Sherman tank from the 70th Tank Battalion. The tank was raised in 1984 with help from local residents and dive shops, and now stands as a memorial to Exercise Tiger. Not far from the monument to villagers, who never came home.

A plaque was erected at Arlington National Cemetery in 1995, inscribed with the words “Exercise Tiger Memorial”. A 5,000-pound stern anchor bears silent witness to the disaster in Mexico, Missouri.

In 2012, a granite memorial was erected at Utah Beach, engraved with the words in French and English: “In memory of the 946 American servicemen who died in the night of 27 April 1944 off the coast of Slapton Sands (G.B.) during exercise Tiger the rehearsals for the D-Day landing on Utah Beach“.

In 1988, volunteers from the Army Brotherhood of Tankers repaired, repainted and re-stenciled an M4 Sherman tank, installing a mirror image of the Slapton memorial at Fort Taber Park in the south-coastal working class city of New Bedford, Massachusetts.

New Bedford veteran’s agent Christopher Gomes lost his right leg during the Iraq War, in 2008. Gomes was succinct that Memorial Day 2016, when he spoke of this difficult chapter in British/American military history. “People only die”, he said, “when they are forgotten about″.

Left – Memorial Day 2018: WW2 Navy combat veteran Vincent Riccardi, Exercise Tiger’s oldest survivor, salutes his fallen comrades at Fort Taber Park in New Bedford, Massachusetts. H/T South Coast Today

Right – The M4 Sherman Tank Tank at the Fort Taber – Fort Rodman Military Museum at Fort Taber Park in New Bedford mirrors the one built to the fallen at Slapton Sands, Devon, England.

The island nation of Great Britain alone escaped occupation, but British armed forces were shattered and defenseless in the face of the German war machine.

The island nation of Great Britain alone escaped occupation, but British armed forces were shattered and defenseless in the face of the German war machine. Hitler ordered his Panzer groups to resume the advance on May 26, while a National Day of Prayer was declared at Westminster Abbey. That night Winston Churchill ordered “Operation Dynamo”. One of the most miraculous evacuations in military history had begun from the beaches of Dunkirk.

Hitler ordered his Panzer groups to resume the advance on May 26, while a National Day of Prayer was declared at Westminster Abbey. That night Winston Churchill ordered “Operation Dynamo”. One of the most miraculous evacuations in military history had begun from the beaches of Dunkirk. Larger ships were boarded from piers, while thousands waded into the surf and waited in shoulder deep water for smaller vessels. They came from everywhere: merchant marine boats, fishing boats, pleasure craft, lifeboats and tugs. The smallest among them was the 14’7″ fishing boat “Tamzine”, now in the Imperial War Museum.

Larger ships were boarded from piers, while thousands waded into the surf and waited in shoulder deep water for smaller vessels. They came from everywhere: merchant marine boats, fishing boats, pleasure craft, lifeboats and tugs. The smallest among them was the 14’7″ fishing boat “Tamzine”, now in the Imperial War Museum. A thousand copies of navigational charts helped organize shipping in and out of Dunkirk, as buoys were laid around Goodwin Sands to prevent strandings. Abandoned vehicles were driven into the water at low tide, weighted down with sand bags and connected by wooden planks, forming makeshift jetties.

A thousand copies of navigational charts helped organize shipping in and out of Dunkirk, as buoys were laid around Goodwin Sands to prevent strandings. Abandoned vehicles were driven into the water at low tide, weighted down with sand bags and connected by wooden planks, forming makeshift jetties. 7,669 were evacuated on the first full day of the evacuation, May 27, and none too soon. The following day, members of the SS Totenkopf Division marched 100 captured members of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment off to a pit, and machine gunned the lot of them. A group of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment were captured that same day, herded into a barn and murdered with grenades.

7,669 were evacuated on the first full day of the evacuation, May 27, and none too soon. The following day, members of the SS Totenkopf Division marched 100 captured members of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment off to a pit, and machine gunned the lot of them. A group of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment were captured that same day, herded into a barn and murdered with grenades.

Most light equipment and virtually all heavy equipment had to be left behind, just to get what remained of the allied armies out alive. But now, with the United States still the better part of a year away from entering the war, the allies had a military fighting force that would live to fight on.

Most light equipment and virtually all heavy equipment had to be left behind, just to get what remained of the allied armies out alive. But now, with the United States still the better part of a year away from entering the war, the allies had a military fighting force that would live to fight on.

There was no future for them in this place. Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. The family emigrated to Israel in May 1949, resuming their musical tour and performing until the group retired in 1955.

There was no future for them in this place. Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. The family emigrated to Israel in May 1949, resuming their musical tour and performing until the group retired in 1955.

With sandbags, explosives, and the device which made the thing work, the total payload was about a thousand pounds on liftoff. The first such device was released on November 3, 1944, beginning the crossing to the west coast of North America. 9,300 such balloons were released with military payloads, between late 1944 and April, 1945.

With sandbags, explosives, and the device which made the thing work, the total payload was about a thousand pounds on liftoff. The first such device was released on November 3, 1944, beginning the crossing to the west coast of North America. 9,300 such balloons were released with military payloads, between late 1944 and April, 1945. In 1945, intercontinental weapons were more in the realm of science fiction. As these devices began to appear, American authorities theorized that they originated with submarine-based beach assaults, German POW camps, and even the internment camps into which the Roosevelt administration herded Japanese Americans.

In 1945, intercontinental weapons were more in the realm of science fiction. As these devices began to appear, American authorities theorized that they originated with submarine-based beach assaults, German POW camps, and even the internment camps into which the Roosevelt administration herded Japanese Americans.

American authorities were alarmed. Anti-personnel and incendiary bombs were relatively low grade threats. Not so the biological weapons Japanese military authorities were known to be developing at the infamous Unit 731, in northern China.

American authorities were alarmed. Anti-personnel and incendiary bombs were relatively low grade threats. Not so the biological weapons Japanese military authorities were known to be developing at the infamous Unit 731, in northern China.

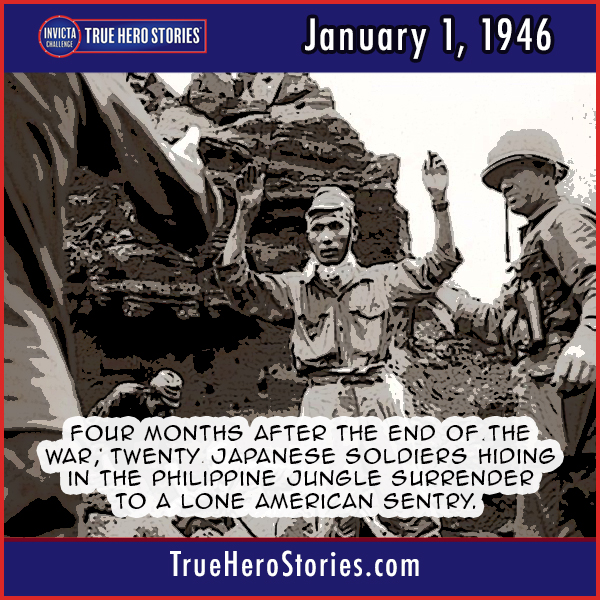

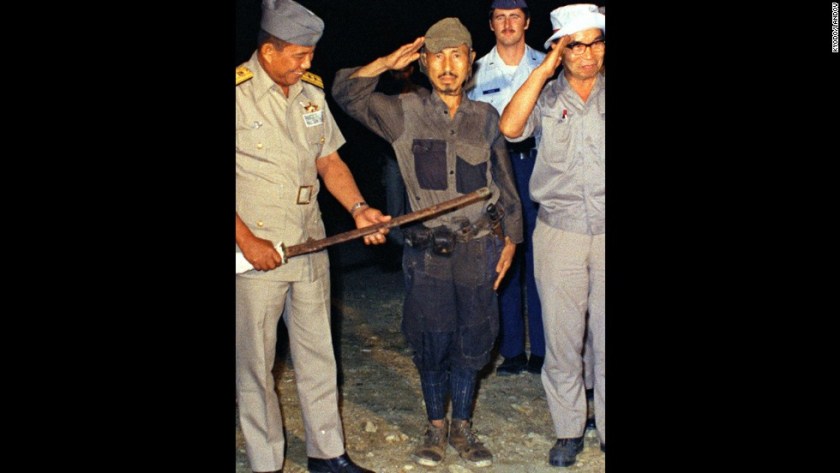

Imperial Japan would rage for another 33 years.

Imperial Japan would rage for another 33 years.

Several went on to fight for the Viet Minh against French troops in Indochina.

Several went on to fight for the Viet Minh against French troops in Indochina.

On February 7, the 71st Infantry and supporting tanks reached Ramree town where they found determined Japanese resistance, the town falling two days later. Naval forces blockaded small tributaries called “chaungs”, which the retreating Japanese used in their flight to the mainland. A Japanese air raid damaged an allied destroyer on the 11th as a flotilla of small craft crossed the strait, to rescue survivors of the garrison. By February 17, Japanese resistance had come to an end.

On February 7, the 71st Infantry and supporting tanks reached Ramree town where they found determined Japanese resistance, the town falling two days later. Naval forces blockaded small tributaries called “chaungs”, which the retreating Japanese used in their flight to the mainland. A Japanese air raid damaged an allied destroyer on the 11th as a flotilla of small craft crossed the strait, to rescue survivors of the garrison. By February 17, Japanese resistance had come to an end.

The “Battle of the Atlantic” lasted 5 years, 8 months and 5 days, ranging from the Irish Sea to the Gulf of Mexico, from the Caribbean to the Arctic Ocean. Winston Churchill would describe this as “the dominating factor all through the war. Never for a moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome”.

The “Battle of the Atlantic” lasted 5 years, 8 months and 5 days, ranging from the Irish Sea to the Gulf of Mexico, from the Caribbean to the Arctic Ocean. Winston Churchill would describe this as “the dominating factor all through the war. Never for a moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome”. New weapons and tactics would shift the balance first in favor of one side, and then to the other. In the end over 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships would be sunk to the bottom of the ocean, compared with the loss of 783 U-boats.

New weapons and tactics would shift the balance first in favor of one side, and then to the other. In the end over 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships would be sunk to the bottom of the ocean, compared with the loss of 783 U-boats.

and crews to breathe while running submerged. Venturer was on batteries when the first sounds were detected, giving the British sub the stealth advantage but sharply limiting the time frame in which it could act.

and crews to breathe while running submerged. Venturer was on batteries when the first sounds were detected, giving the British sub the stealth advantage but sharply limiting the time frame in which it could act. With four incoming at as many depths, the German sub didn’t have time to react. Wolfram was only just retrieving his snorkel and converting to electric, when the #4 torpedo struck. U-864 imploded and sank, instantly killing all 73 aboard.

With four incoming at as many depths, the German sub didn’t have time to react. Wolfram was only just retrieving his snorkel and converting to electric, when the #4 torpedo struck. U-864 imploded and sank, instantly killing all 73 aboard.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. A year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. A year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

BBC History reported that, “within a week, a quarter of the population of Britain would have a new address”.

BBC History reported that, “within a week, a quarter of the population of Britain would have a new address”. The evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly, considering. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’

The evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly, considering. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’ In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.”

In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.” Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were, and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians.

Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were, and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians. By October 1940, the “

By October 1940, the “

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

20,000 died from sickness or hunger, or were murdered by Japanese guards on the 60 mile “death march” from Bataan, into captivity at Cabanatuan prison and others.

20,000 died from sickness or hunger, or were murdered by Japanese guards on the 60 mile “death march” from Bataan, into captivity at Cabanatuan prison and others. Two rice rations per day, fewer than 800 calories, were supplemented by the occasional animal or insect caught and killed inside camp walls, or by the rare food items smuggled in by civilian visitors.

Two rice rations per day, fewer than 800 calories, were supplemented by the occasional animal or insect caught and killed inside camp walls, or by the rare food items smuggled in by civilian visitors. On December 14, some fifty to sixty soldiers of the Japanese 14th Area Army in Palawan doused 150 prisoners with gasoline and set them on fire, machine gunning or clubbing any who tried to escape the flames. Some thirty to forty managed to escape the killing zone, only to be hunted down and murdered, one by one. Eleven managed to escape the slaughter, and lived to tell the tale. 139 were burned, clubbed or machine gunned to death.

On December 14, some fifty to sixty soldiers of the Japanese 14th Area Army in Palawan doused 150 prisoners with gasoline and set them on fire, machine gunning or clubbing any who tried to escape the flames. Some thirty to forty managed to escape the killing zone, only to be hunted down and murdered, one by one. Eleven managed to escape the slaughter, and lived to tell the tale. 139 were burned, clubbed or machine gunned to death.

He dressed and shaved, put on his best clothes, and walked out of camp. Passing guerrillas found him and passed him to a tank destroyer. Give the man points for style. A few days later, Edwin Rose strolled into 6th army headquarters, a cane tucked under his arm.

He dressed and shaved, put on his best clothes, and walked out of camp. Passing guerrillas found him and passed him to a tank destroyer. Give the man points for style. A few days later, Edwin Rose strolled into 6th army headquarters, a cane tucked under his arm.

You must be logged in to post a comment.