We tend to look at WW2 in a kind of historical box, with a beginning and an end. In reality, we feel the effects of WWII to this day. Just as the modern boundaries (and many of the problems) of the Middle East were shaped by WWI, the division of the Korean Peninsula was borne of WWII.

Korea’s brief period of modern sovereignty ended in 1910, when the country was annexed by Imperial Japan. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, Korea was divided into two occupied zones; the north held by the Soviet Union and the south by the United States.

The Cairo Declaration of 1943 called for a unified Korea, but cold war tensions hardened the separation. By 1948, the two Koreas had separate governments, each with its own diametrically opposite governing philosophy.

Kim Il-sung came to power in North Korea in 1946, nationalizing key industries and collectivizing land and other means of production. South Korea declared statehood in May 1948, under the vehemently anti-communist military strongman, Syngman Rhee.

Both governments sought control of the Korean peninsula, but the 1948-49 withdrawal of Soviet and most American forces left the south holding the weaker hand. Escalating border conflicts along the 38th parallel led to war when the North, with assurances of support from the Soviet Union and Communist China, invaded South Korea in June 1950.

Sixteen countries sent troops to South Korea’s aid, about 90% of whom were Americans. The Soviets sent material aid to the North, while Communist China sent troops. The Korean War lasted three years, causing the death or disappearance of over 2,000,000 on all sides, combining military and civilian.

Sixteen countries sent troops to South Korea’s aid, about 90% of whom were Americans. The Soviets sent material aid to the North, while Communist China sent troops. The Korean War lasted three years, causing the death or disappearance of over 2,000,000 on all sides, combining military and civilian.

The Korean War ended in July 1953. The two sides technically remain at war to this day, staring each other down over millions of land mines in a fortified demilitarized zone spanning the width of the country.

The night-time satellite image of the two Koreas, tells the story of what happened next. In the south, the Republic of Korea (ROK) developed into a successful constitutional Republic, a G-20 nation with an economy ranking 11th in the world in nominal GDP, and 13th in terms of purchasing power parity.

The night-time satellite image of the two Koreas, tells the story of what happened next. In the south, the Republic of Korea (ROK) developed into a successful constitutional Republic, a G-20 nation with an economy ranking 11th in the world in nominal GDP, and 13th in terms of purchasing power parity.

In the “Democratic People’s Republic of Korea” (DPRK), Kim Il-sung built a cult of personality, a communist totalitarian dictatorship established under an ideology known as “Juche”, (JOO-chay).

The term translates as “independent stand” or “spirit of self-reliance”, its first known reference in a speech given by Kim Il-sung on December 28, 1955. Theoretically based on independent thought, economic self-sufficiency and self-reliance in defense, “independence” applies to the collective, not to the individual, from whom absolute loyalty to the revolutionary party leader is required.

In practice, this principle puts one man at the center and above it all. According to recent amendments to the DPRK constitution, that man will always be a well-fed member of the Kim family.

Son of the founder of the Juche Ideal, Kim Jung Il, was an enthusiastic film buff. In a move that would make Caligula blush, Kim had South Korean film maker Shin Sang Ok kidnapped along with his actress ex-wife, Choi Eun Hee. After four years spent starving in a North Korean gulag, the couple accepted Kim’s “suggestion” to re-marry and go to work for him, producing the less-than-box-office-smash “Pulgasari”, a kind of North Korean Godzilla film.

Son of the founder of the Juche Ideal, Kim Jung Il, was an enthusiastic film buff. In a move that would make Caligula blush, Kim had South Korean film maker Shin Sang Ok kidnapped along with his actress ex-wife, Choi Eun Hee. After four years spent starving in a North Korean gulag, the couple accepted Kim’s “suggestion” to re-marry and go to work for him, producing the less-than-box-office-smash “Pulgasari”, a kind of North Korean Godzilla film.

The couple escaped, unlike untold numbers of unfortunates “recruited” with the help of chloroform soaked rags.

North Korea broke ground on the Ryugyong hotel in 1987, just in time for the Seoul Olympics the following year. 105 stories tall with eight revolving floors, the Ryugyong would be the tallest hotel in the world, if it ever opens.

Begun thirty years ago by the grandfather of the current “Dear Leader”, the “Hotel of Doom” is still under construction. The project appears to hold particular significance for Kim Jung Un, who probably needs to show that he can get things done. Perhaps 2018 will be the year. For now, Travelocity notes under all its Pyongyang attractions: “Our online travel partners don’t provide prices for this accommodation, but we can search other options in Pyongyang”.

As the tallest unoccupied building in the world rose above the streets of Pyongyang, anywhere from 1 to 3 million North Koreans starved to death during the 1990s.

Authorities warned the nation of yet another famine impending in March 2016, the state-run newspaper Rodong Sinmun editorializing that “We may have to go on an arduous march, during which we will have to chew the roots of plants once again.”

The DPRK government enforces its will with a murderous system of gulags, torture chambers and concentration camps, complete with crematoria. A 2014 UN report estimated that “hundreds of thousands of political prisoners” have died in North Korean gulags over the past 50 years amid “unspeakable atrocities.”

As of 2010, the DPRK Military had 7,679,000 active, reserve, and paramilitary personnel, in a nation of 25,000,000. Over 30% of the nation’s population, absorbing nearly 21% of GDP. Today, that military is under the personal control of a 33-year old who had his half-brother assassinated in Kuala Lumpur, using VX nerve gas.

The Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and the “Hermit Kingdom” in North Korea have had more or less “normal” relations, since the 1979 Iranian Revolution. The relationship isn’t all moonbeams and lollipops, but a cordial hatred for the United States have bound the two together, the last remaining members of President George W. Bush’ “Axis of Evil”.

Recently, the Obama administration concluded a nuclear “deal” with Iran, replete with secret “side deals” and sealed with pallets of taxpayer cash. CIA Director John Brennan conceded last September that his agency is “monitoring” whether North Korea is providing Iran with clandestine nuclear assistance. It doesn’t seem a stretch. There have been arms sales and “peaceful nuclear cooperation” between the two, since the 1980s.

The relationship between the two is now guided by the steady hands of the “Death to America” mullahs, and a man who banished Christmas and ordered North Koreans to worship his grandmother, as a god. Two among five nations on earth, designated by the US State Department, as “State Sponsors of Terrorism.” I can’t imagine what could go wrong.

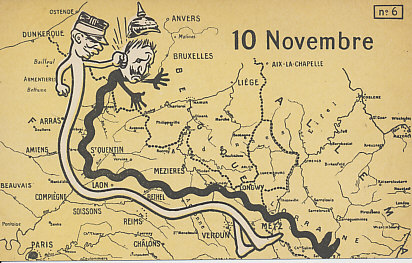

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers. German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”.

German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”. Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

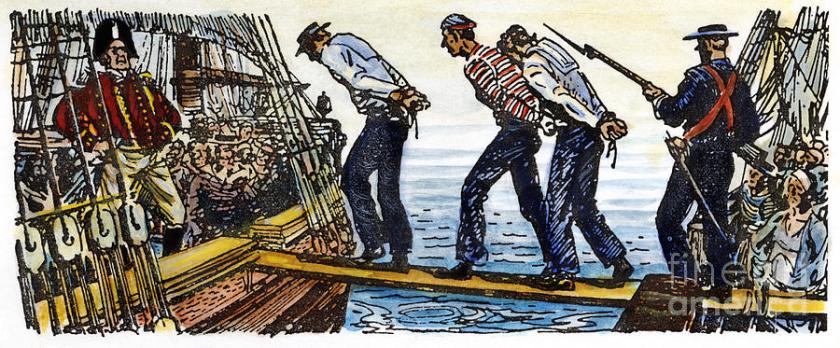

The American public was outraged and there were calls for war in 1807, when HMS Leopard overtook the USS Chesapeake, kidnapping three American-born sailors and one British deserter, leaving another three dead and 18 wounded.

The American public was outraged and there were calls for war in 1807, when HMS Leopard overtook the USS Chesapeake, kidnapping three American-born sailors and one British deserter, leaving another three dead and 18 wounded. Outside of the British Royal Navy, the practice of kidnapping people to serve as shipboard labor was known as “crimping”. Low wages combined with the gold rushes of the 19th century left the waterfront painfully short of manpower, skilled and unskilled, alike. “Boarding Masters” had the job of putting together ship’s crews, and were paid for each recruit. There was strong incentive to produce as many able bodies, as possible. Unwilling men were “shanghaied” by means of trickery, intimidation or violence, most often rendered unconscious and delivered to waiting ships, for a fee.

Outside of the British Royal Navy, the practice of kidnapping people to serve as shipboard labor was known as “crimping”. Low wages combined with the gold rushes of the 19th century left the waterfront painfully short of manpower, skilled and unskilled, alike. “Boarding Masters” had the job of putting together ship’s crews, and were paid for each recruit. There was strong incentive to produce as many able bodies, as possible. Unwilling men were “shanghaied” by means of trickery, intimidation or violence, most often rendered unconscious and delivered to waiting ships, for a fee.

San Francisco political bosses William T. Higgins, (R) and Chris “Blind Boss” Buckley (D) were both notable crimps, and well positioned to look after their political interests. Notorious crimps such as Joseph “Frenchy” Franklin and George Lewis were elected to the California state legislature. There was no better spot, from which to ensure that no legislation would interfere with such a lucrative trade.

San Francisco political bosses William T. Higgins, (R) and Chris “Blind Boss” Buckley (D) were both notable crimps, and well positioned to look after their political interests. Notorious crimps such as Joseph “Frenchy” Franklin and George Lewis were elected to the California state legislature. There was no better spot, from which to ensure that no legislation would interfere with such a lucrative trade. Imagine the hangover the next morning, to wake up and find you’re now at sea, bound for somewhere in the far east. Regulars knew about the trap door and avoided it at all costs, knowing that anyone going over there, was “fair game”.

Imagine the hangover the next morning, to wake up and find you’re now at sea, bound for somewhere in the far east. Regulars knew about the trap door and avoided it at all costs, knowing that anyone going over there, was “fair game”.

Stranded and alone in the high Andes, meager supplies soon gave out. A few chocolate bars, assorted snacks and several bottles of wine. It was gone within days, as the survivors scoured the wreckage for crumbs. They ate leather from suitcases, tore apart seats hoping to find straw, finding nothing but inedible foam. Nothing grew at this altitude. There were no animals. There was nothing in that desolate place but metal, glass, ice and rock. And the frozen bodies of the dead.

Stranded and alone in the high Andes, meager supplies soon gave out. A few chocolate bars, assorted snacks and several bottles of wine. It was gone within days, as the survivors scoured the wreckage for crumbs. They ate leather from suitcases, tore apart seats hoping to find straw, finding nothing but inedible foam. Nothing grew at this altitude. There were no animals. There was nothing in that desolate place but metal, glass, ice and rock. And the frozen bodies of the dead.

The Juan Valdez of the coffee commercials is an “Arriero”, a man who transports goods using pack animals. Parrado and Canessa had hiked for almost two weeks when they were building a fire by a river, and spotted such a man on the other side. Sergio Catalán probably didn’t believe his eyes at first, but he shouted across the river. “Tomorrow”.

The Juan Valdez of the coffee commercials is an “Arriero”, a man who transports goods using pack animals. Parrado and Canessa had hiked for almost two weeks when they were building a fire by a river, and spotted such a man on the other side. Sergio Catalán probably didn’t believe his eyes at first, but he shouted across the river. “Tomorrow”.

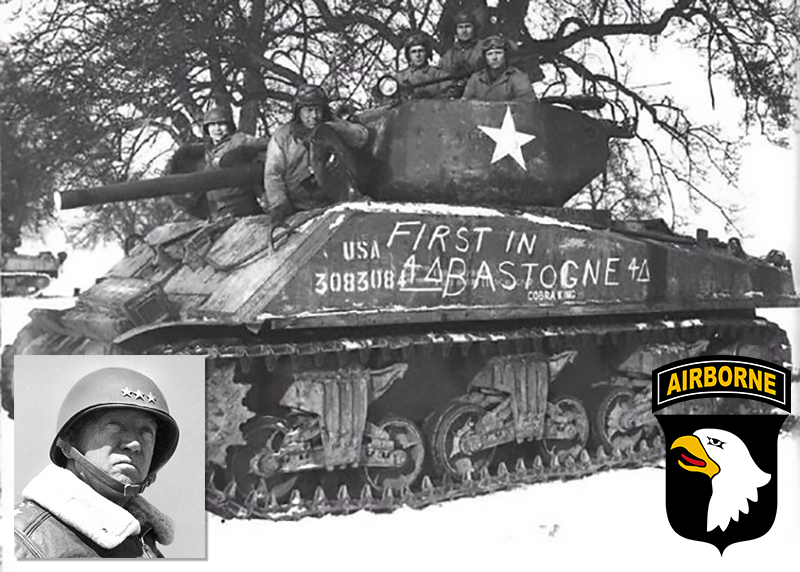

Augusta Marie Chiwy (“Shee-wee”) was the bi-racial daughter of a Belgian veterinarian and a Congolese mother, she never knew.

Augusta Marie Chiwy (“Shee-wee”) was the bi-racial daughter of a Belgian veterinarian and a Congolese mother, she never knew. Chiwy married after the war, and rarely talked about her experience in Bastogne. It took King a full 18 months to coax the story out of her. The result was the 2015 Emmy award winning historical documentary, “Searching for Augusta, The Forgotten Angel of Bastogne”.

Chiwy married after the war, and rarely talked about her experience in Bastogne. It took King a full 18 months to coax the story out of her. The result was the 2015 Emmy award winning historical documentary, “Searching for Augusta, The Forgotten Angel of Bastogne”.

A “Fidelity Medallion” was awarded to three militia men in 1780, for the capture of

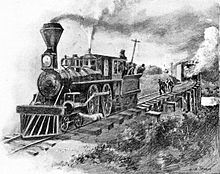

A “Fidelity Medallion” was awarded to three militia men in 1780, for the capture of  An Army version of the medal was created the following July, first awarded to six Union soldiers for hijacking the Confederate locomotive, “The General”. Leader of the raid James Andrews was caught and hanged as a Union spy. He alone was judged ineligible for the medal of honor, as he was a civilian.

An Army version of the medal was created the following July, first awarded to six Union soldiers for hijacking the Confederate locomotive, “The General”. Leader of the raid James Andrews was caught and hanged as a Union spy. He alone was judged ineligible for the medal of honor, as he was a civilian. Few soldiers on the Civil War battlefield had a quicker route to death’s door, than the color bearer. National and regimental flags were all-important sources of inspiration and communication.

Few soldiers on the Civil War battlefield had a quicker route to death’s door, than the color bearer. National and regimental flags were all-important sources of inspiration and communication.

Father

Father

The battered aircraft was completely alone and struggling to maintain altitude, the American pilot well inside German air space, when he looked to his left and saw his worst nightmare. Three feet from his wing tip was the sleek gray shape of a German fighter, the pilot so close that the two men were looking into one another’s eyes.

The battered aircraft was completely alone and struggling to maintain altitude, the American pilot well inside German air space, when he looked to his left and saw his worst nightmare. Three feet from his wing tip was the sleek gray shape of a German fighter, the pilot so close that the two men were looking into one another’s eyes.

In February, Dickens took a train north to the factory town of Lowell, visiting the textile mills and speaking with the “mill girls”, the women who worked there. Once again, he seemed to believe that his native England suffered in the comparison. Dickens spoke of the new buildings and the well dressed, healthy young women who worked in them, no doubt comparing them with the teeming slums and degraded conditions in London.

In February, Dickens took a train north to the factory town of Lowell, visiting the textile mills and speaking with the “mill girls”, the women who worked there. Once again, he seemed to believe that his native England suffered in the comparison. Dickens spoke of the new buildings and the well dressed, healthy young women who worked in them, no doubt comparing them with the teeming slums and degraded conditions in London. Dickens left with a copy of “The Lowell Offering”, a literary magazine written by those same mill girls, which he later described as “four hundred good solid pages, which I have read from beginning to end.”

Dickens left with a copy of “The Lowell Offering”, a literary magazine written by those same mill girls, which he later described as “four hundred good solid pages, which I have read from beginning to end.” The research which followed was published in the form of a thesis, later fleshed out to a full-length book:

The research which followed was published in the form of a thesis, later fleshed out to a full-length book:

You must be logged in to post a comment.