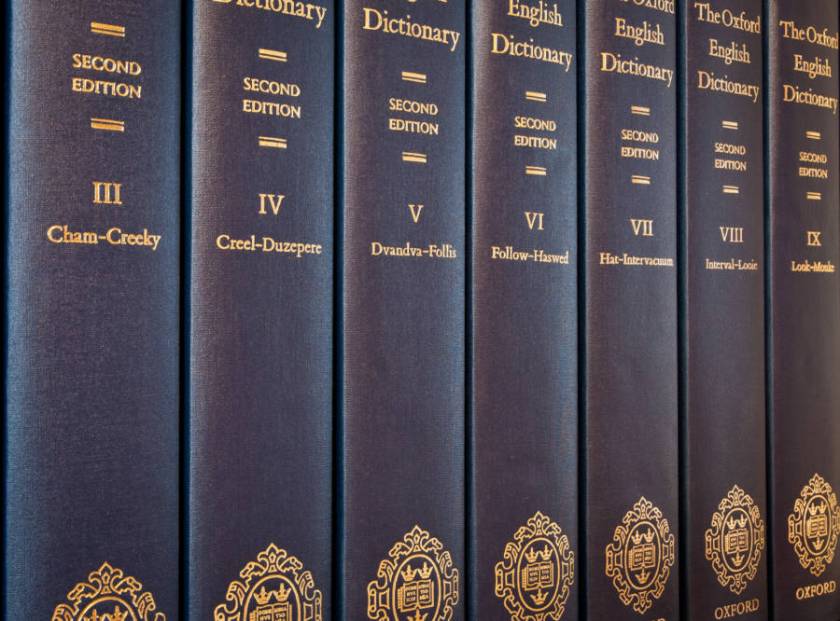

For the great reference works of the English language, the beginnings were often surprisingly modest. Encyclopedia Britannica was first published on this day in 1768 in Edinburgh, Scotland: part of the Scottish enlightenment. Webster’s dictionary got its beginnings with a single infantrymen of the American Revolution, who went on to codify what would become the standardized system of spelling for “American English“. In Noah Webster’s dictionary, ‘colour’ became ‘color’, and programme’ became ‘program’, a novel concept at a time when the thought of a “correct“ way of spelling, was a new and unfamiliar idea.

Among the entire catalog of works there is no tale so queer as the Oxford English dictionary, and the convicted murderer who helped bring it into being. From an insane asylum, no less.

Dissatisfied with what were at that time a spare four reference works including Webster’s dictionary, the Philological society of London first discussed what was to become the standard reference work of the English language, in 1857. The work was expected to take 10 years in compilation and cover some 64,000 pages. The editors were off by sixty years. Five years into the project, the team had made it all the way to “ant“.

William Chester Minor was a physician around this time, serving the Union army during the American Civil War.

The role of this experience in the man’s later psychosis, is impossible to know. Minor was in all likelihood a paranoid schizophrenic, a condition poorly understood in his day.

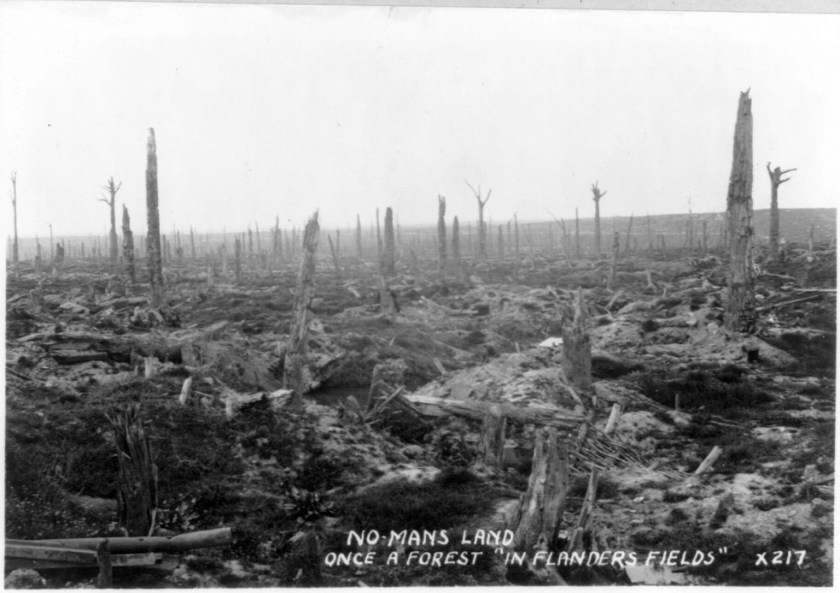

As a combat surgeon, Minor saw things that no man was ever meant to see. Terrible mutilation was inflicted on both sides at the 1864 Battle of the Wilderness. Hundreds were wounded and unable to get out of the way of the brush fire, burning alive those sufferers too broken to move, before the horrified eyes of comrades and enemies, alike. One soldier would later write: It was as though “hell itself had usurped the place of earth“.

Dr. Minor was ordered to brand the forehead of an Irish deserter, with the letter “D”. The episode scarred the soldier, and left the doctor with paranoid delusions that the Irish were coming to ‘get him’.

As a child born to New England missionaries working in Ceylon, Minor was well adjusted to the idea of foreign travel, as a means of dealing with travail. He took a military pension and moved to London in 1871, to escape the demons who were by that time, closing in.

One day, Minor shot and killed one George Merritt, a stoker who was walking to work. He believed the man had broken into his room. The trial was published widely, the “Lambeth Tragedy” revealing the full extent of Minor’s delusional state, to the public.

Minor was judged not guilty on grounds of insanity, and remanded “until Her Majesty’s Pleasure be known”, to the Broadmoor institution for the criminally insane. Victorian England was by no means ‘enlightened’ by modern standards, and inmates were always referred to as ‘criminals’ and ‘lunatics’. Never as ‘patients’. Yet Broadmoor, located on 290 acres in the village of Crowthorne in Berkshire was England’s newest such asylum, and a long way from previous such institutions.

Minor was housed in block 2, the “Swell Block”, where his military pension and family wealth afforded him two rooms, instead of the usual one. In time, Minor acquired so many books that one room was converted to a library. Surprisingly, it was Merritt’s widow Eliza, who delivered many of the books. The pair became friends, and Minor used a portion of his wealth to “pay” for his crime, and to help the widow raise her six kids.

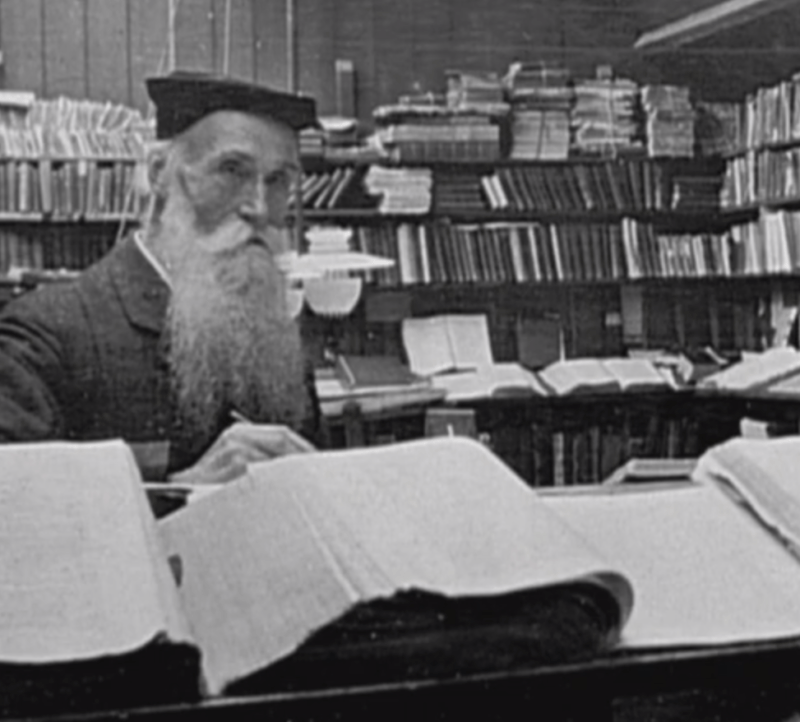

Dr. James Murray assumed editorship of the “Big Dictionary” of English in 1879, and issued an appeal in magazines and newspapers, for outside contributions. Whether this seemed a shot at redemption to William Minor or merely something to do with his time is anyone’s guess, but Minor had nothing but time. And books.

William Minor collected his first quotation in 1880 and continued to do so for twenty years, always signing his submissions: Broadmoor, Crowthorne, Berkshire.

The scope of the man’s work was prodigious, he himself an enigma, assumed to be some country gentlemen. Perhaps one of the overseers, at the asylum.

In 1897, “The Surgeon of Crowthorne” failed to attend the Great Dictionary dinner. Dr. Murray decided to meet his mysterious contributor in person and finally did so, four years later. In his cell. Oh, to have been a fly on the wall, when this Oxford don was ushered into the office of Broadmoor’s director, only to learn that the man he looked for, was an inmate.

Dr. Minor would carefully index and document each entry, which editors compared with the earliest such word use submitted by other lexicographers. In this manner, over 10,000 of his submissions made it into the finished work, including the words ‘colander’, ‘countenance’ and ‘ulcerated’.

By 1902, Minor’s paranoid delusions had crowded out his mind. His submissions came to an end. What monsters lurked inside the man’s head is anyone’s guess. Home Secretary Winston Churchill ordered Minor to be removed back home to the United States, following a 1910 episode in which Minor emasculated himself, with a knife.

The madman lived out the last ten years of his life, in various institutions for the criminally insane. William Chester Minor died in 1920 and went to his rest in a small inauspicious grave, in Connecticut.

Over seventy years in compilation, only one single individual is credited with more entries to the greatest reference work in the history of the English language, than this one murderer, working from a home for lunatics.

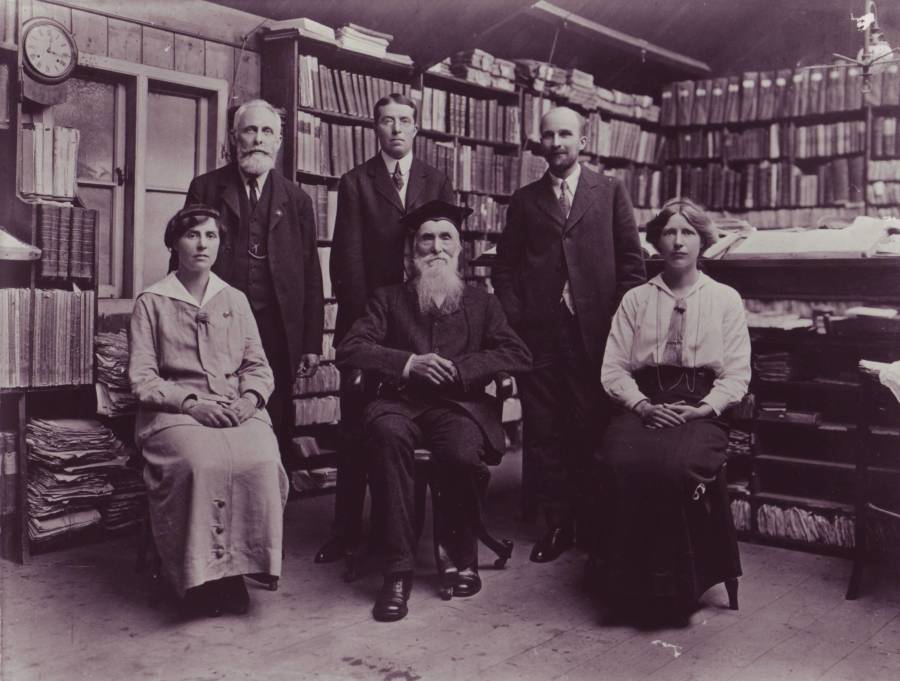

Feature image, top of page: Dr. Murray and his Oxford University editorial team, 1915. H/T allthatsinteresting.com

At one point during this period, then-Senator Julius Caesar stepped to the rostrum to have his say. He was handed a paper and, reading it, stuck the note in his toga and resumed his speech. Cato, Caesar’s implacable foe, stood in the senate and demanded that Caesar read the note. It’s nothing, replied the future emperor, but Cato thought he had caught the hated Caesar red handed. “I demand you read that note”, he said, or words to that effect. He wouldn’t let it go.

At one point during this period, then-Senator Julius Caesar stepped to the rostrum to have his say. He was handed a paper and, reading it, stuck the note in his toga and resumed his speech. Cato, Caesar’s implacable foe, stood in the senate and demanded that Caesar read the note. It’s nothing, replied the future emperor, but Cato thought he had caught the hated Caesar red handed. “I demand you read that note”, he said, or words to that effect. He wouldn’t let it go.

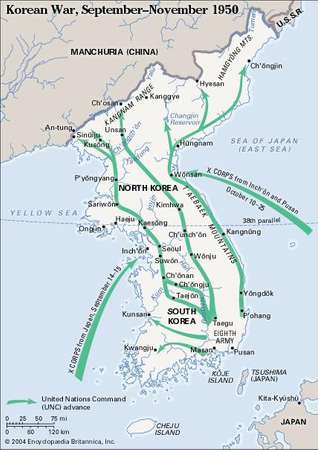

On June 25, 1950, ten divisions of the North Korean People’s Army launched a surprise invasion of their neighbor to the south. The 38,000-man army of the Republic of Korea didn’t have a chance against 89,000 men sweeping down in six columns from the north. Within hours, the shattered remnants of the army of the ROK and its government, were streaming south toward the capital of Seoul.

On June 25, 1950, ten divisions of the North Korean People’s Army launched a surprise invasion of their neighbor to the south. The 38,000-man army of the Republic of Korea didn’t have a chance against 89,000 men sweeping down in six columns from the north. Within hours, the shattered remnants of the army of the ROK and its government, were streaming south toward the capital of Seoul.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi came to power in 1941, following the Commonwealth/Soviet invasion of the Empire of Iran which forced the abdication of his father.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi came to power in 1941, following the Commonwealth/Soviet invasion of the Empire of Iran which forced the abdication of his father.

The Iranian constitution of 1906 was supplanted by popular referendum on this day in 1979, when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was proclaimed rahbar-e mo’azzam-e irān, Supreme Leader of the Islamic Revolution.

The Iranian constitution of 1906 was supplanted by popular referendum on this day in 1979, when Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was proclaimed rahbar-e mo’azzam-e irān, Supreme Leader of the Islamic Revolution. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini is gone now, but his influence is very much alive. If you want a fun read sometime, download the constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Khomeini is personally named in the document. Three times.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini is gone now, but his influence is very much alive. If you want a fun read sometime, download the constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Khomeini is personally named in the document. Three times.

What historians call the First Indochina War, many contemporaries called “la sale guerre”, or “dirty war”. The government forbade the use of metropolitan recruits, fearing that that would make the war more unpopular than it already was. Instead, French professional soldiers and units of the French Foreign Legion were augmented with colonial troops, including Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities.

What historians call the First Indochina War, many contemporaries called “la sale guerre”, or “dirty war”. The government forbade the use of metropolitan recruits, fearing that that would make the war more unpopular than it already was. Instead, French professional soldiers and units of the French Foreign Legion were augmented with colonial troops, including Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Vietnamese ethnic minorities.

The French staff formulated their battle plan, based on the assumption that it was impossible for the Viet Minh to place enough artillery on the surrounding high ground, due to the rugged terrain. Communist forces didn’t possess enough artillery to do serious damage anyway. Or so they thought.

The French staff formulated their battle plan, based on the assumption that it was impossible for the Viet Minh to place enough artillery on the surrounding high ground, due to the rugged terrain. Communist forces didn’t possess enough artillery to do serious damage anyway. Or so they thought. “Beatrice” was the first fire base to fall, then “Gabrielle” and “Anne-Marie”. Viet Minh controlled 90% of the airfield by the 22nd of April, making even parachute drops next to impossible. On May 7, Vo ordered an all-out assault of 25,000 troops against the 3,000 remaining in garrison. By nightfall it was over. The last words from the last radio man were “The enemy has overrun us. We are blowing up everything. Vive la France!”

“Beatrice” was the first fire base to fall, then “Gabrielle” and “Anne-Marie”. Viet Minh controlled 90% of the airfield by the 22nd of April, making even parachute drops next to impossible. On May 7, Vo ordered an all-out assault of 25,000 troops against the 3,000 remaining in garrison. By nightfall it was over. The last words from the last radio man were “The enemy has overrun us. We are blowing up everything. Vive la France!”

American support for the south increased as the French withdrew theirs. By the late 1950s, the United States were sending technical and financial aid in expectation of social and land reform. By 1960, the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF, or “Viet Cong”) had taken to murdering Diem supported village leaders. President John Fitzgerald Kennedy responded by sending 1,364 American advisers into South Vietnam, in 1961.

American support for the south increased as the French withdrew theirs. By the late 1950s, the United States were sending technical and financial aid in expectation of social and land reform. By 1960, the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF, or “Viet Cong”) had taken to murdering Diem supported village leaders. President John Fitzgerald Kennedy responded by sending 1,364 American advisers into South Vietnam, in 1961.

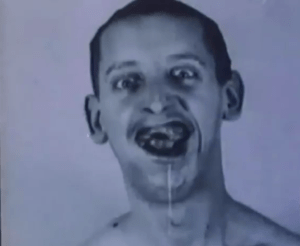

The worldwide Encephalitis Lethargica epidemic afflicted some five million people between 1915 and 1924. One-third of sufferers died in the acute phase of the disease, a higher mortality rate than the Spanish flu of 1918-’19. Many of those who survived never returned to their pre-existing state of “aliveness”, and lived the rest of their lives institutionalized, as described above.

The worldwide Encephalitis Lethargica epidemic afflicted some five million people between 1915 and 1924. One-third of sufferers died in the acute phase of the disease, a higher mortality rate than the Spanish flu of 1918-’19. Many of those who survived never returned to their pre-existing state of “aliveness”, and lived the rest of their lives institutionalized, as described above. Individual cases continue to pop up, but have never assumed the pandemic proportions of 1915-’24. Further study is needed but, perversely, such study is only possible given more cases of the disease. For now, Encephalitis Lethargica must remain one of the great medical mysteries of the twentieth century. An epidemiological conundrum, locked away in a nightmare closet of forgotten memory.

Individual cases continue to pop up, but have never assumed the pandemic proportions of 1915-’24. Further study is needed but, perversely, such study is only possible given more cases of the disease. For now, Encephalitis Lethargica must remain one of the great medical mysteries of the twentieth century. An epidemiological conundrum, locked away in a nightmare closet of forgotten memory.

Untold thousands of Tootsie roll wrappers littered the seventy-eight miles back to the sea. Most credit their survival to the energy provided by the chocolate candy. It turns out that frozen tootsie rolls make a swell putty too, useful for patching up busted hoses and vehicles.

Untold thousands of Tootsie roll wrappers littered the seventy-eight miles back to the sea. Most credit their survival to the energy provided by the chocolate candy. It turns out that frozen tootsie rolls make a swell putty too, useful for patching up busted hoses and vehicles.

On the third came Longstreet’s assault, better known as “Pickett’s charge”. 13,000 Confederate soldiers came out of the tree line at Seminary Ridge, 1¼-miles distant from the Federal line.

On the third came Longstreet’s assault, better known as “Pickett’s charge”. 13,000 Confederate soldiers came out of the tree line at Seminary Ridge, 1¼-miles distant from the Federal line.

You must be logged in to post a comment.