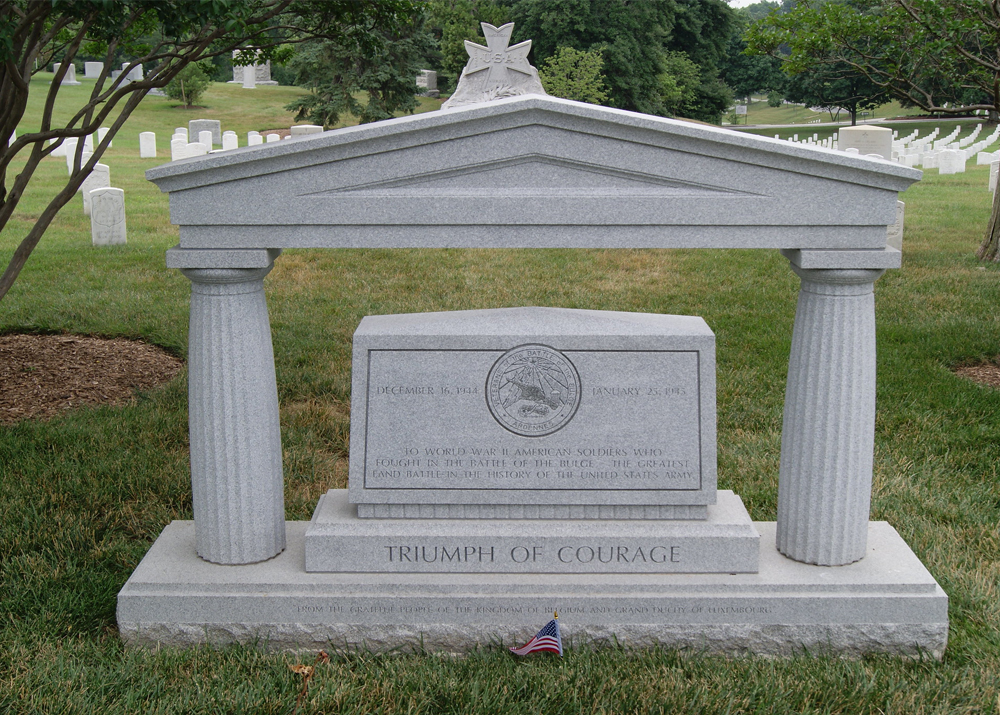

The Oxford English Dictionary defines Monument as “A statue, building, or other structure erected to commemorate a notable person or event”.

Our nation’s most hallowed ground is itself such a monument – Memorial Avenue extending across the Potomac connecting Arlington House, the former home of Confederate General Robert E. Lee with the Lincoln Memorial at the opposite end symbolizing the immutable bond, between North and South.

The first military burial at Arlington National Cemetery was that of Private William Henry Christman, 67th Pennsylvania Infantry, interred on May 13, 1864. Two more joined Christman that day, the trickle soon turning into a flood. By the end of the war between the states, that number was 17,000 and rising.

In modern times, an average week will see 80 to 100 burials in the 612 acres of Arlington.

Nineteen years ago, a news release from the Department of Defense reported “Private First Class Michael A. Arciola, 20, of Elmsford, New York, died February 15, 2005, in Al Ramadi, Iraq, from injuries sustained from enemy small arms fire. Arciola was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 503d Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, Camp Casey, Korea”.

Nineteen years ago, a news release from the Department of Defense reported “Private First Class Michael A. Arciola, 20, of Elmsford, New York, died February 15, 2005, in Al Ramadi, Iraq, from injuries sustained from enemy small arms fire. Arciola was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 503d Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, Camp Casey, Korea”.

Private Arciola joined a quarter-million buried in our nation’s most hallowed ground on March 31. Two hundred or more mourners attended his funeral, a tribute befitting the tragedy of the loss of one so young.

Sixteen others were buried that same Friday. Most were considerably older. Some brought only a dozen or so mourners. Others had no friends or family members whatsoever, on-hand to say goodbye.

Save for a volunteer from a group called, Arlington Ladies.

In 1948, Air Force Chief of Staff General Hoyt Vandenberg and the general’s wife Gladys, regularly attended funeral services at Arlington National cemetery.

Sometimes, a military chaplain was the only person present at these services. Both husband and wife felt that a member of the Air Force family should be present at these funerals. Before long, Gladys began to invite other officer’s wives. Over time, a group of women from the Officer’s Wives Club formed specifically for the purpose.

Sometimes, a military chaplain was the only person present at these services. Both husband and wife felt that a member of the Air Force family should be present at these funerals. Before long, Gladys began to invite other officer’s wives. Over time, a group of women from the Officer’s Wives Club formed specifically for the purpose.

In 1973, General Creighton Abrams’ wife Julia did the same for the Army, forming a group calling themselves “Arlington Ladies”. Groups of Navy and Coast guard wives followed suit in 1985, and 2006.

Traditionally, the Marine Corps Commandant sends an official representative of the Corps to all Marine funerals. The Marine Corps branch of the Arlington Ladies were formed in 2016.

Arlington Ladies’ Chairman Margaret Mensch explained “We’ve been accused of being professional mourners, but that isn’t true. I fight that perception all the time. What we’re doing is paying homage to Soldiers who have given their lives for our country.”

The casual visitor cannot help but being struck with the solemnity of such an occasion. Air Force Ladies’ Chairman Sue Ellen Lansell spoke of one service where the only other guest was “one elderly gentlemen who stood at the curb and would not come to the grave site. He was from the Soldier’s Home in Washington, D. C. One soldier walked up to invite him closer, but he said no, he was not family”.

The casual visitor cannot help but being struck with the solemnity of such an occasion. Air Force Ladies’ Chairman Sue Ellen Lansell spoke of one service where the only other guest was “one elderly gentlemen who stood at the curb and would not come to the grave site. He was from the Soldier’s Home in Washington, D. C. One soldier walked up to invite him closer, but he said no, he was not family”.

The organization was traditionally formed of current or former military wives. Today their number includes daughters and even one “Arlington Gentleman”. At one time they came alone, or in pairs. Today, 145 or so volunteers from four military branches are a recognized part of all funeral ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery, their motto: “No Soldier will ever be buried alone.”

The volunteer arrives with a military escort from the Navy or the United States Army 3rd Infantry Regiment, the “Old Guard”. The horse-drawn caisson arrives from the old post chapel, carrying the flag draped casket. Joining the procession, she will quietly walk to the burial site, her arm inside that of her escort. A few words are spoken over the deceased, followed by the three-volley salute. Off in the distance, a solitary bugler sounds Taps.

The folded flag is presented to the grieving widow, or next of kin. Only then will she break her silence, stepping forward with a word of condolence and two cards: one from the service branch Chief of Staff and his wife and a second, from herself.

Joyce Johnson buried her husband Lieutenant Colonel Dennis Johnson in 2001, a victim of the Islamist terrorist attack on the Pentagon. Johnson remembers the Arlington Ladies’ volunteer as “a touchingly, human presence in a sea of starched uniforms and salutes”. Three years later Johnson herself paid it forward, becoming one of the Arlington Ladies.

Any given funeral may be that of a young military service member killed in service to the nation, or a veteran of Korea or WWII who spent his last days in the old soldier’s home. It could be a four-star General or a Private. It matters not a whit.

“We’re not professional mourners. We’re here because we’re representing the Air Force family and because, one day, our families are going to be sitting there in that chair”. – Sandra Griffin, Air Force volunteer, Arlington Ladies

Individual volunteers attend about five funerals a day, sometimes as many as eight. As with the Tomb of the Unknown sentinels who hold their vigil heedless of weather, funeral services pay no mind, to weather conditions. The funeral will proceed on the date and time scheduled irrespective of rain, snow or heat. Regardless of weather, a representative of the Arlington Ladies will be in attendance.

The job of the Arlington Ladies is to honor, not to grieve. But it doesn’t always work out that way. Linda Willey of the Air Force Ladies describes the difficulty of burying Pentagon friends after 9/11, even as pieces of debris littered the cemetery. Paula McKinley of the Navy Ladies still chokes up over the hug of a ten-year old girl who had lost both parents. Margaret Mensch speaks of the heartbreak of burying one of her own young escorts after he was killed in Afghanistan, in 2009.

Barbara Benson was herself a soldier, an Army flight nurse during WWII. She is the longest serving Arlington Lady. “I always try to add something personal”, Benson said, “especially for a much older woman. I always ask how long they were married. They like to tell you they were married 50 or 60 years…I don’t know how to say it really, I guess because I identify with Soldiers. That was my life for 31 years, so it just seems like the natural thing to do.”

Elinore Riedel was chairman of the Air Force Ladies during the War in Vietnam, when none of the other military branches had women representatives. “Most of the funerals were for young men,” she said. “I saw little boys running little airplanes over their father’s coffins. It is a gripping thing, and it makes you realize the awful sacrifices people made. Not only those who died, but those left behind.”

Mrs. Reidel is a minister’s daughter, who grew up watching her father serve those in need. “It doesn’t matter whether you know a person or not”, she said, “whether you will ever see them again. It calls upon the best in all of us to respond to someone in deep despair. I call it grace…I honestly feel we all need more grace in our lives.”

One day, the United States Supreme Court would rule the act an unlawful taking and compensate Lee family descendants.

One day, the United States Supreme Court would rule the act an unlawful taking and compensate Lee family descendants.

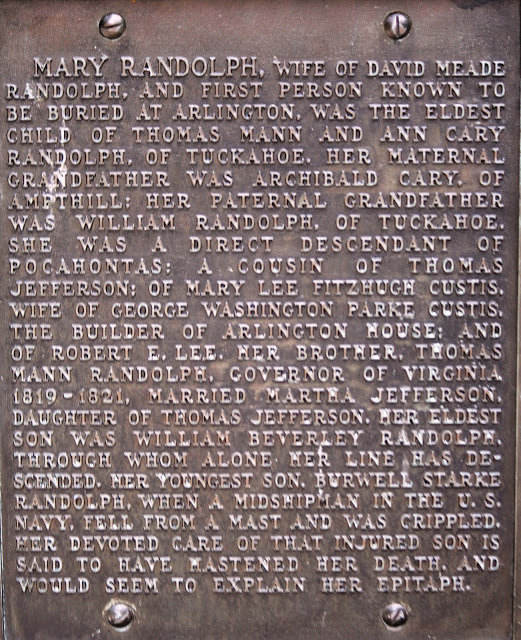

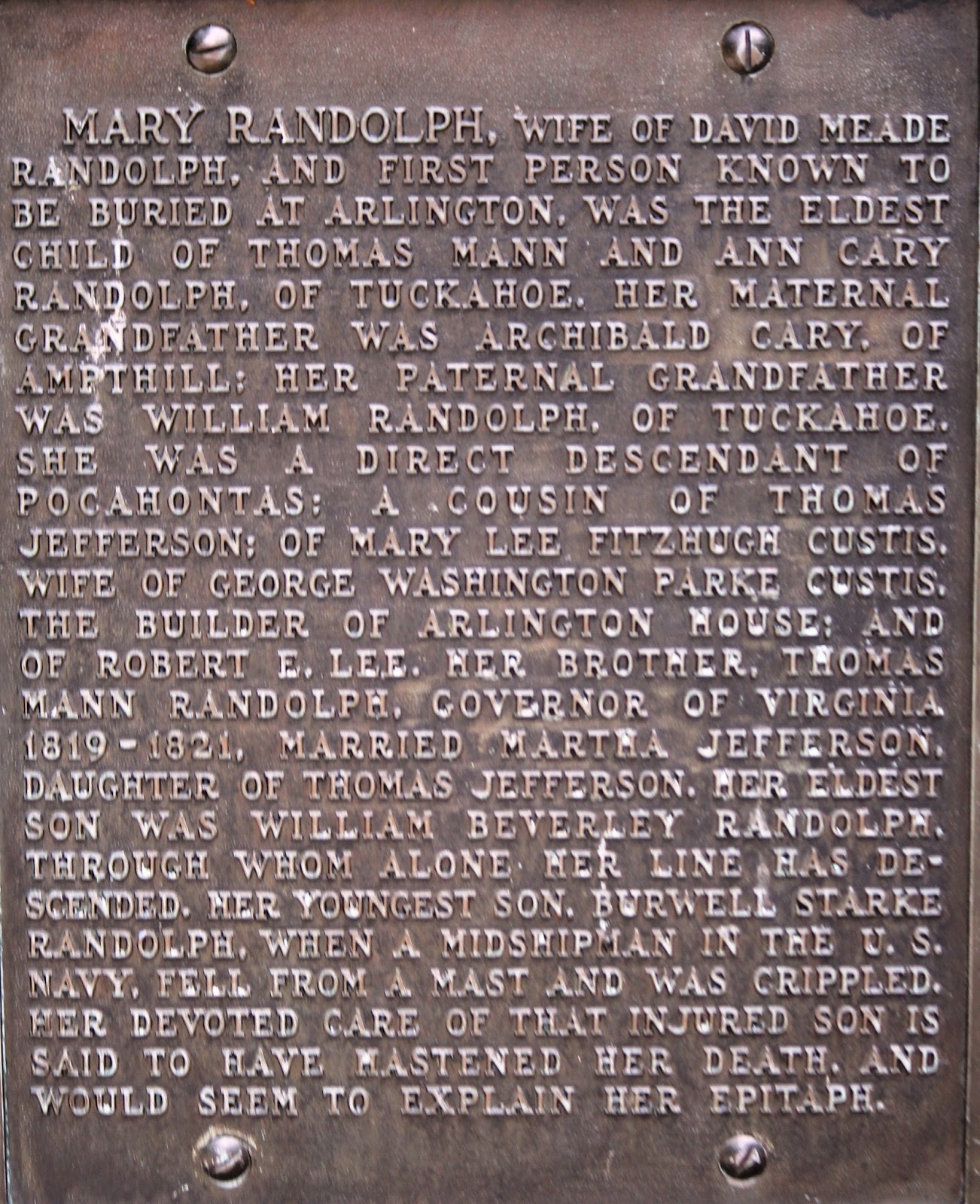

Private Christman was the first military burial, but not the first. One had come before. When Private Christman went to his rest in our nation’s most hallowed ground, his grave joined that of Mary Randolph, laid to rest some thirty-six years earlier.

Private Christman was the first military burial, but not the first. One had come before. When Private Christman went to his rest in our nation’s most hallowed ground, his grave joined that of Mary Randolph, laid to rest some thirty-six years earlier.

Mary Randolph, a direct descendant of

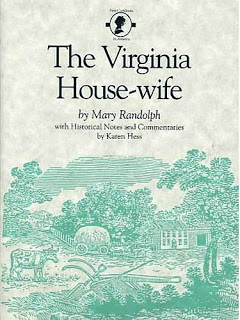

Mary Randolph, a direct descendant of  Mary Randolph is best known as the author of America’s first regional cookbook, “The Virginia House-wife” and known to some, as “The Methodical Cook”.

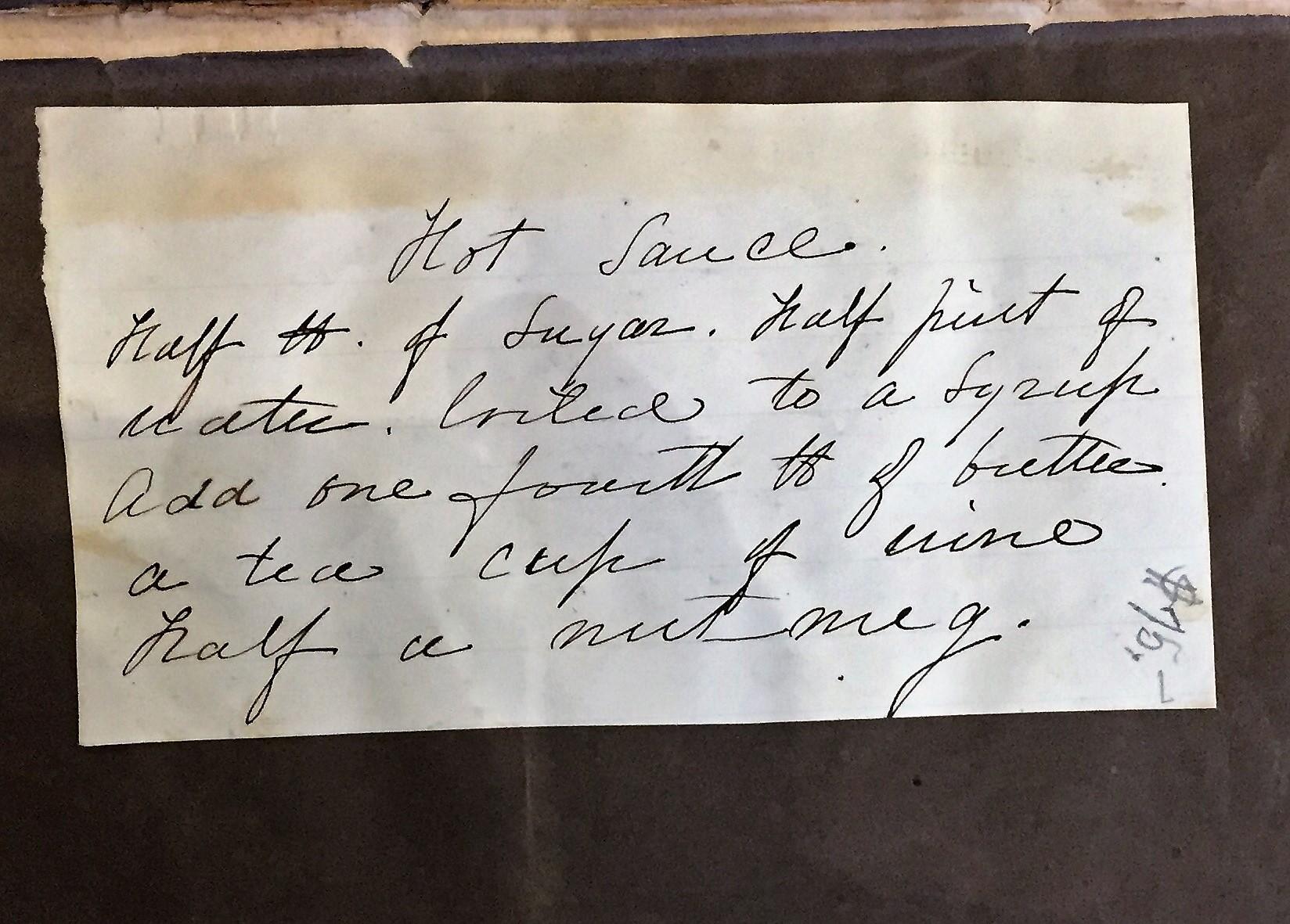

Mary Randolph is best known as the author of America’s first regional cookbook, “The Virginia House-wife” and known to some, as “The Methodical Cook”. Mary Randolph, wife of David Meade Randolph, was an early advocate of the now-common use of herbs, spices and wines in cooking.

Mary Randolph, wife of David Meade Randolph, was an early advocate of the now-common use of herbs, spices and wines in cooking.

Some 40 million were killed in the Great War, either that or maimed or simply, vanished. It was a mind bending number, equivalent to the entire population in 1900 of either France, or the United Kingdom. Equal to the combined populations of the bottom two-thirds of every nation on the planet. Every woman, man, puppy, boy and girl.

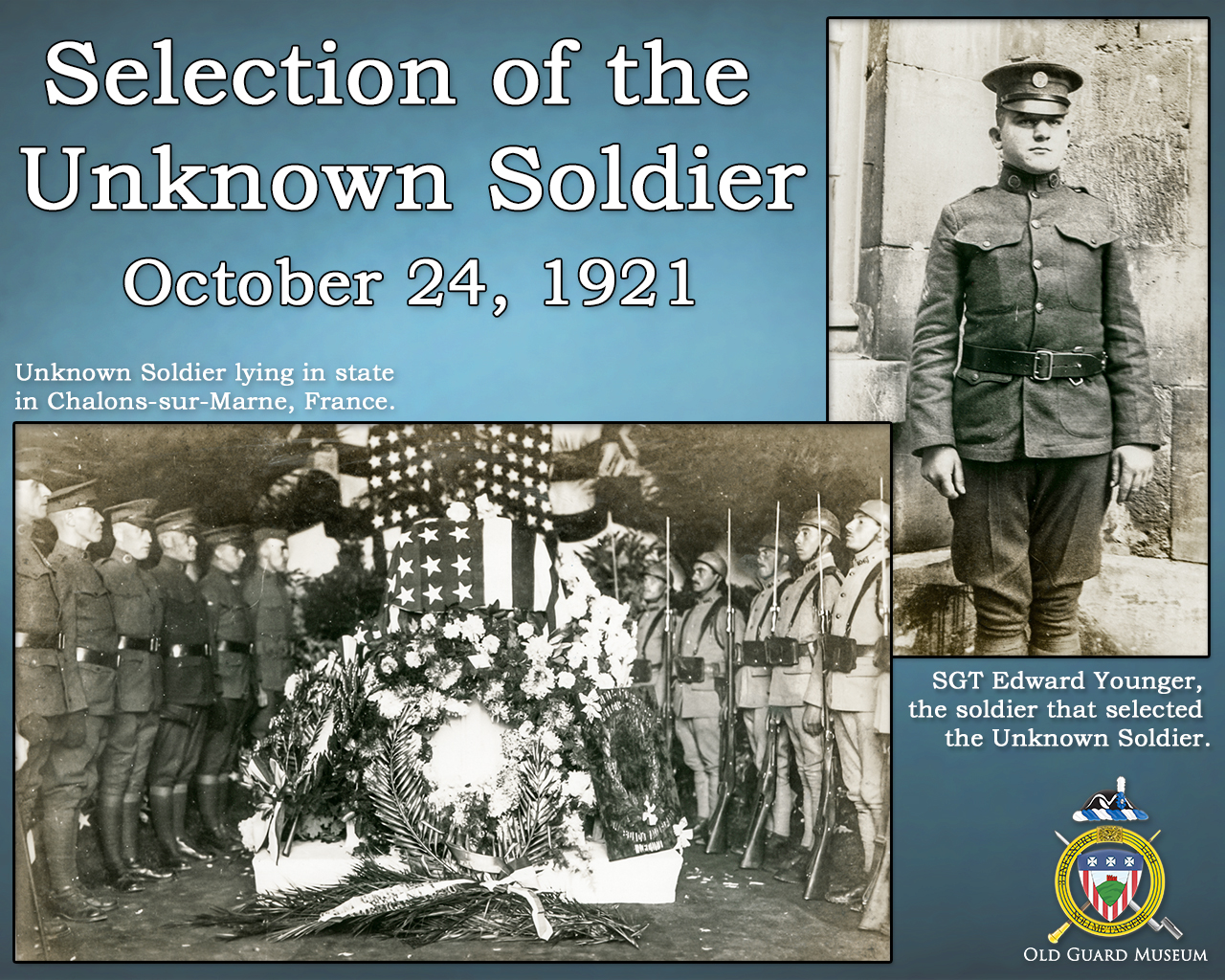

Some 40 million were killed in the Great War, either that or maimed or simply, vanished. It was a mind bending number, equivalent to the entire population in 1900 of either France, or the United Kingdom. Equal to the combined populations of the bottom two-thirds of every nation on the planet. Every woman, man, puppy, boy and girl. The idea of honoring the unknown dead from the “War to end all Wars” originated in Europe. Reverend David Railton remembered a rough cross from somewhere on the western front, with the words written in pencil: “An Unknown British Soldier”.

The idea of honoring the unknown dead from the “War to end all Wars” originated in Europe. Reverend David Railton remembered a rough cross from somewhere on the western front, with the words written in pencil: “An Unknown British Soldier”.

Passing between two lines of French and American officials, Sgt. Younger entered the room, alone. Slowly, he circled the four caskets, three times, before at last stopping at the third from the left. “What caused me to stop” he later said, “I don’t know. It was as though something had pulled me“. Younger placed the roses on the casket, drew himself to attention, and saluted. This was the one.

Passing between two lines of French and American officials, Sgt. Younger entered the room, alone. Slowly, he circled the four caskets, three times, before at last stopping at the third from the left. “What caused me to stop” he later said, “I don’t know. It was as though something had pulled me“. Younger placed the roses on the casket, drew himself to attention, and saluted. This was the one. On November 11, the casket was removed from the Rotunda of the Capitol and escorted under military guard to the amphitheater at

On November 11, the casket was removed from the Rotunda of the Capitol and escorted under military guard to the amphitheater at  With three salvos of artillery, the rendering of Taps and the National Salute, the ceremony was brought to a close and the 12-ton marble cap placed over the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The west facing side bears this inscription:

With three salvos of artillery, the rendering of Taps and the National Salute, the ceremony was brought to a close and the 12-ton marble cap placed over the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The west facing side bears this inscription:

Fourteen years ago, a news release from the Department of Defense reported “Private First Class Michael A. Arciola, 20, of Elmsford, New York, died February 15, 2005, in Al Ramadi, Iraq, from injuries sustained from enemy small arms fire. Arciola was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 503d Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, Camp Casey, Korea”.

Fourteen years ago, a news release from the Department of Defense reported “Private First Class Michael A. Arciola, 20, of Elmsford, New York, died February 15, 2005, in Al Ramadi, Iraq, from injuries sustained from enemy small arms fire. Arciola was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 503d Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, Camp Casey, Korea”.

Sometimes, a military chaplain was the only one present at these services. Both Vandenbergs felt that a member of the Air Force family should be present at these funerals. Gladys began to invite other officer’s wives. Over time, a group of women from the Officer’s Wives Club were formed for the purpose.

Sometimes, a military chaplain was the only one present at these services. Both Vandenbergs felt that a member of the Air Force family should be present at these funerals. Gladys began to invite other officer’s wives. Over time, a group of women from the Officer’s Wives Club were formed for the purpose.

The casual visitor cannot help but being struck with the solemnity of such an occasion. Air Force Ladies’ Chairman Sue Ellen Lansell spoke of one service where the only other guest was “one elderly gentlemen who stood at the curb and would not come to the grave site. He was from the Soldier’s Home in Washington, D. C. One soldier walked up to invite him closer, but he said no, he was not family”.

The casual visitor cannot help but being struck with the solemnity of such an occasion. Air Force Ladies’ Chairman Sue Ellen Lansell spoke of one service where the only other guest was “one elderly gentlemen who stood at the curb and would not come to the grave site. He was from the Soldier’s Home in Washington, D. C. One soldier walked up to invite him closer, but he said no, he was not family”.

The last line of the inscription, “a victim to maternal love and duty” refers to her youngest surviving son, Midshipman Burwell Starke Randolph, who suffered a fall from a high mast in 1817, while serving in the Navy. Both of his legs were broken and never healed properly. When Mary passed away in 1828, Randolph remarked that his mother had sacrificed her own life in care of his.

The last line of the inscription, “a victim to maternal love and duty” refers to her youngest surviving son, Midshipman Burwell Starke Randolph, who suffered a fall from a high mast in 1817, while serving in the Navy. Both of his legs were broken and never healed properly. When Mary passed away in 1828, Randolph remarked that his mother had sacrificed her own life in care of his. Mrs. Randolph was an early advocate of the now-common use of herbs, spices and wines in cooking. Her recipe for apple fritters calls for slices of apple marinated in a combination of brandy, white wine, sugar, cinnamon, and lemon rind.

Mrs. Randolph was an early advocate of the now-common use of herbs, spices and wines in cooking. Her recipe for apple fritters calls for slices of apple marinated in a combination of brandy, white wine, sugar, cinnamon, and lemon rind.

In 1866, the Quartermaster ordered the remains of 2,111 unknown Civil War dead to be exhumed and placed inside a vault in the Lees’ rose garden.

In 1866, the Quartermaster ordered the remains of 2,111 unknown Civil War dead to be exhumed and placed inside a vault in the Lees’ rose garden.

You must be logged in to post a comment.