In the time of Henry VIII, British military outlays averaged 29.4% as a percentage of central government expenses. That number skyrocketed to 74.6% in the 18th century, and never dropped below 55%.

The Seven Years’ War alone, fought on a global scale from 1756 – ‘63, saw England borrow the unprecedented sum of £58 million, doubling the national debt and straining the British economy.

For the American colonies, the conflict took the form of the French and Indian War. Across the “pond”, the never-ending succession of English wars meant that, not only were colonists left alone to run their own affairs, but individual colonists learned an interdependence of one upon another, resulting in significant economic growth during every decade of the 1700s.

For the American colonies, the conflict took the form of the French and Indian War. Across the “pond”, the never-ending succession of English wars meant that, not only were colonists left alone to run their own affairs, but individual colonists learned an interdependence of one upon another, resulting in significant economic growth during every decade of the 1700s.

Some among the British government saw in the American colonies, the classically “Liberal” notion of the Free Market, as described by intellectuals such as John Locke: “No People ever yet grew rich by Policies,” wrote Sir Dudley North. “But it is Peace, Industry, and Freedom that brings Trade and Wealth“. These, were in the minority. The prevailing attitude at the time, saw the colonies as the beneficiary of much of British government expense. These wanted some help, picking up the tab.

Several measures were taken to collect revenues during the 1760s. Colonists bristled at what was seen as heavy handed taxation policies. The Sugar Act, the Currency Act: in one 12-month period alone, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, Quartering Act, and the Declaratory Act, while deputizing Royal Navy Sea Officers to enforce customs laws in colonial ports.

The merchants and traders of Boston specifically cited “the late war” and the expenses related to it, concluding the Boston Non-Importation Agreement of August 1, 1768. The agreement prohibited the importation of a long list of goods, ending with the statement ”That we will not, from and after the 1st of January 1769, import into this province any tea, paper, glass, or painters colours, until the act imposing duties on those articles shall be repealed”.

The ‘Boston Massacre’ of 1770 was a direct result of the tensions between colonists and

the “Regulars” sent to enforce the will of the Crown. Two years later, Sons of Liberty looted and burned the HMS Gaspee in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island.

The Tea Act, passed by Parliament on May 10, 1773, was less a revenue measure than it was an effort to prop up the British East India Company, by that time burdened with debt and holding some eighteen million pounds of unsold tea. The measure actually reduced the price of tea, but Colonists saw it as an effort to buy popular support for taxes already in force, and refused the cargo. In Philadelphia and New York, tea ships were turned away and sent back to Britain while in Charleston, the cargo was left to rot on the docks.

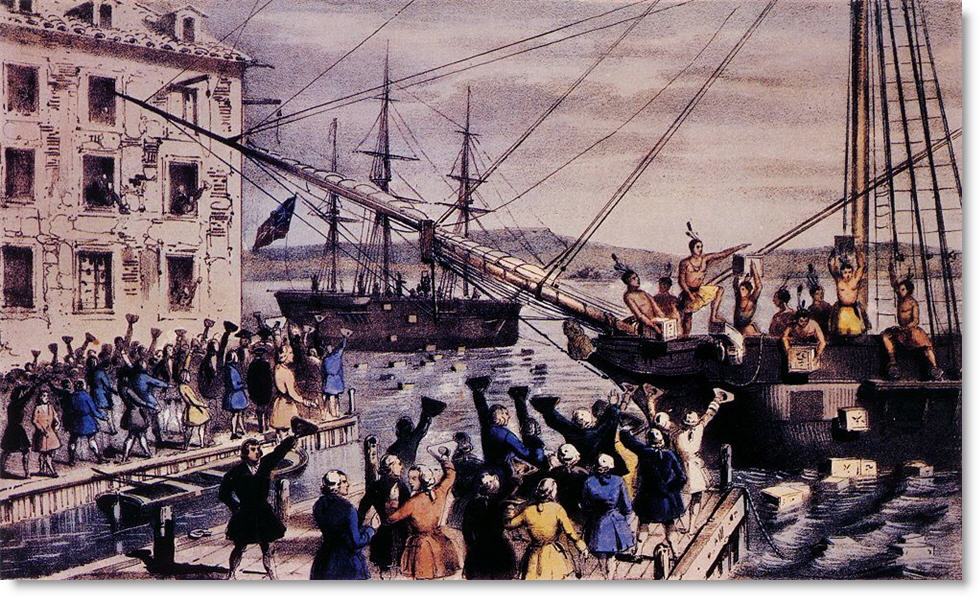

British law required a tea ship to offload and pay customs duty within 20 days, or the cargo was forfeit. The Dartmouth arrived in Boston at the end of November with a cargo of tea, followed by the tea ships Eleanor and Beaver. Samuel Adams called for a meeting at Faneuil Hall on the 29th, which then moved to Old South Meeting House to accommodate the crowd. 25 men were assigned to watch Dartmouth, making sure she didn’t unload.

7,000 gathered at Old South Meeting House on December 16th, 1773, the last day of deadline, for Dartmouth’s cargo. Royal Governor Hutchinson held his ground, refusing the vessel permission to leave. Adams announced that “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

7,000 gathered at Old South Meeting House on December 16th, 1773, the last day of deadline, for Dartmouth’s cargo. Royal Governor Hutchinson held his ground, refusing the vessel permission to leave. Adams announced that “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

That night, anywhere between 30 and 130 Sons of Liberty, many dressed as Mohawk Indians, boarded the three ships in Boston Harbor. There they threw 342 chests of tea, 90,000 pounds in all, into Boston Harbor. £9,000 worth of tea was destroyed, worth about $1.5 million in today’s dollars.

In the following months, other protesters staged their own “Tea Parties”, destroying imported British tea in New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, and Greenwich, NJ. There was even a second Boston Tea Party on March 7, 1774, when 60 Sons of Liberty, again dressed as Mohawks, boarded the “Fortune”. This time they dumped a ton and one-half of the stuff, into the harbor. That October in Annapolis Maryland, the Peggy Stewart was burned to the water line.

For decades to come, the December 16 incident in Boston Harbor was blithely referred to as “the destruction of the tea.” The earliest newspaper reference to “tea party” wouldn’t come down to us, until 1826.

John Crane of Braintree is one of the few original tea partiers ever identified, and the only man injured in the event. An original member of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati and early member of the Sons of Liberty, Crane was struck on the head by a tea crate and thought to be dead. His body was carried away and hidden under a pile of shavings at a Boston cabinet maker’s shop. It must have been a sight when John Crane “rose from the dead”, the following morning.

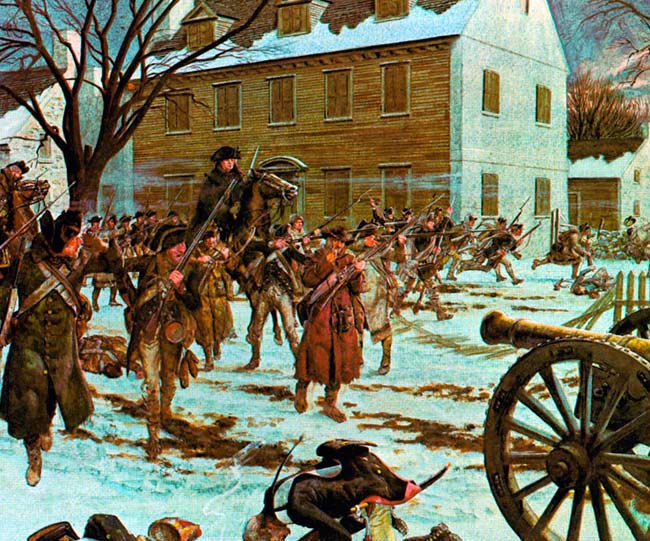

Great Britain responded with the “Intolerable Acts” of 1774, including the occupation of  Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would remember the events of that day as “The shot heard ’round the world”.

Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would remember the events of that day as “The shot heard ’round the world”.

Admiral Rodney pretty much had his way. The census of 1790 shows 8,124 on the Dutch island nation. In 1950, the population stood at only 790. It would take 150 years from Rodney’s departure, before tourism even began to restore the economic well-being of the tiny island.

Admiral Rodney pretty much had his way. The census of 1790 shows 8,124 on the Dutch island nation. In 1950, the population stood at only 790. It would take 150 years from Rodney’s departure, before tourism even began to restore the economic well-being of the tiny island.

First raised above the town square on October 19, 1774, the flag’s canton featured the Union Jack, on the blood red field of the British Red Ensign. The

First raised above the town square on October 19, 1774, the flag’s canton featured the Union Jack, on the blood red field of the British Red Ensign. The

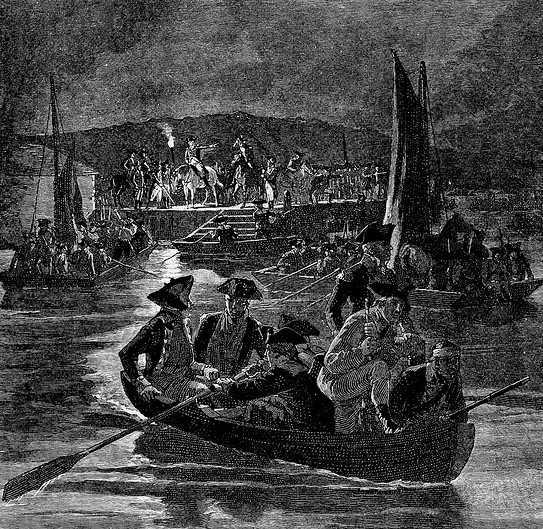

It’s not well known that the American Revolution was fought in the midst of a smallpox pandemic. General George Washington was an early proponent of vaccination, an untold benefit to the American war effort, but a fever broke out among shipbuilders which nearly brought their work to a halt.

It’s not well known that the American Revolution was fought in the midst of a smallpox pandemic. General George Washington was an early proponent of vaccination, an untold benefit to the American war effort, but a fever broke out among shipbuilders which nearly brought their work to a halt.

200 were able to escape to shore, the last of whom was Benedict Arnold himself, who personally torched his own flagship, the Congress, before leaving it behind, flag still flying.

200 were able to escape to shore, the last of whom was Benedict Arnold himself, who personally torched his own flagship, the Congress, before leaving it behind, flag still flying.

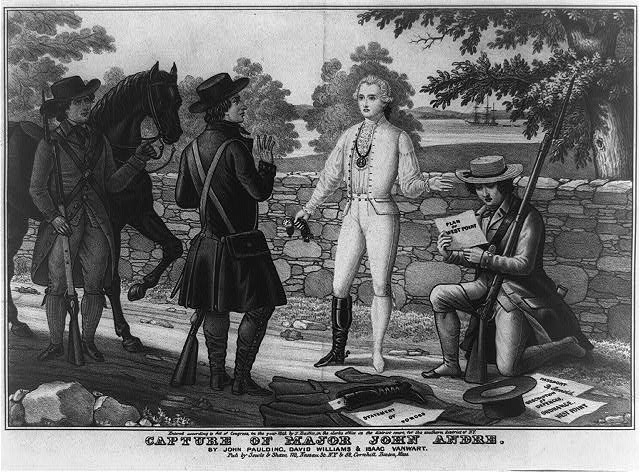

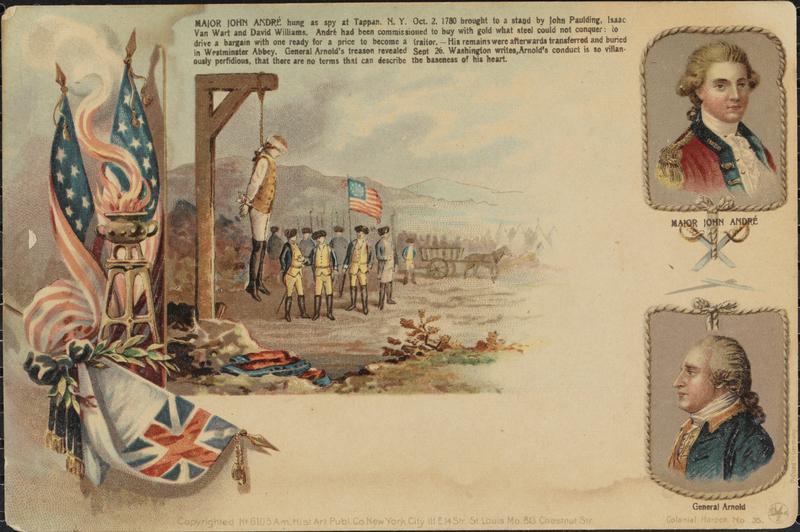

Long afterward, in the early 20th century, the descendants of Major-General Lord Charles Grey returned the painting to the United States, indicating that André had probably looted Franklin’s home under orders from General Grey, himself. A Gentleman always, it would explain the man’s inability to defend his own actions. Today, that oil portrait of Benjamin Franklin hangs in the White House.

Long afterward, in the early 20th century, the descendants of Major-General Lord Charles Grey returned the painting to the United States, indicating that André had probably looted Franklin’s home under orders from General Grey, himself. A Gentleman always, it would explain the man’s inability to defend his own actions. Today, that oil portrait of Benjamin Franklin hangs in the White House.

There was no official record taken of Nathan Hale’s last words, yet we know from eyewitness statement, that the man died with the same clear-eyed personal courage, with which he had lived.

There was no official record taken of Nathan Hale’s last words, yet we know from eyewitness statement, that the man died with the same clear-eyed personal courage, with which he had lived.

1776 started out well for the cause of American independence, when the twenty-six-year-old bookseller Henry Knox emerged from a six week slog through a New England winter, at the head of a “

1776 started out well for the cause of American independence, when the twenty-six-year-old bookseller Henry Knox emerged from a six week slog through a New England winter, at the head of a “ The Continental Congress adopted the

The Continental Congress adopted the

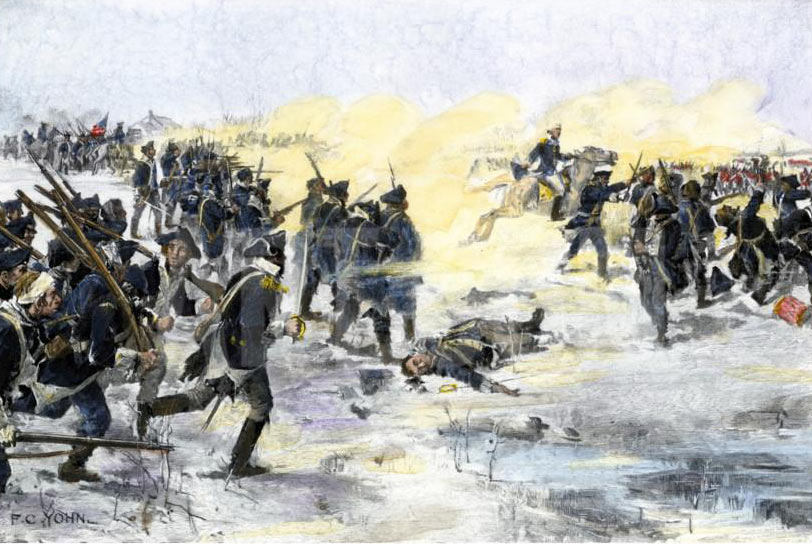

The British line advanced up Breed’s Hill twice that afternoon, Patriot fire decimating their number and driving the survivors back down the hill to reform and try again.

The British line advanced up Breed’s Hill twice that afternoon, Patriot fire decimating their number and driving the survivors back down the hill to reform and try again.

Lafayette’s wife Adrienne gave birth to their first child on one such visit, a baby boy the couple would name Georges Washington Lafayette.

Lafayette’s wife Adrienne gave birth to their first child on one such visit, a baby boy the couple would name Georges Washington Lafayette.

Boston was all but an island in those days, connected to the mainland only be a narrow “neck” of land. A Patriot force some 20,000 strong took positions in the days and weeks that followed, blocking the city and trapping four regiments of British troops (about 4,000 men) inside of the city.

Boston was all but an island in those days, connected to the mainland only be a narrow “neck” of land. A Patriot force some 20,000 strong took positions in the days and weeks that followed, blocking the city and trapping four regiments of British troops (about 4,000 men) inside of the city.

A group of Machias men approached Margaretta from the land and demanded her surrender, but Moore lifted anchor and sailed off in attempt to recover the Polly. A turn of his stern through a brisk wind resulted in a boom and gaff breaking away from the mainsail, crippling the vessel’s navigability. Unity gave chase followed by Falmouth.

A group of Machias men approached Margaretta from the land and demanded her surrender, but Moore lifted anchor and sailed off in attempt to recover the Polly. A turn of his stern through a brisk wind resulted in a boom and gaff breaking away from the mainsail, crippling the vessel’s navigability. Unity gave chase followed by Falmouth.

You must be logged in to post a comment.