It was D+4 following the invasion of Normandy, when the 2nd Panzer Division of the Waffen SS passed through the Limousin region, in west-central France. “Das Reich” carried orders to help stop the Allied advance, when SS-Sturmbannführer Adolf Diekmann received word that SS officer Helmut Kämpfe was being held by French Resistance fighters in the village of Oradour-sur-Vayres.

Diekmann’s battalion sealed off nearby Oradour-sur-Glane, seemingly oblivious to their own confusion between two different villages.

Everyone in the town was ordered to assemble in the village square, for examination of identity papers. The entire population was there plus another half-dozen unfortunates, caught riding bicycles in the wrong place, at the wrong time.

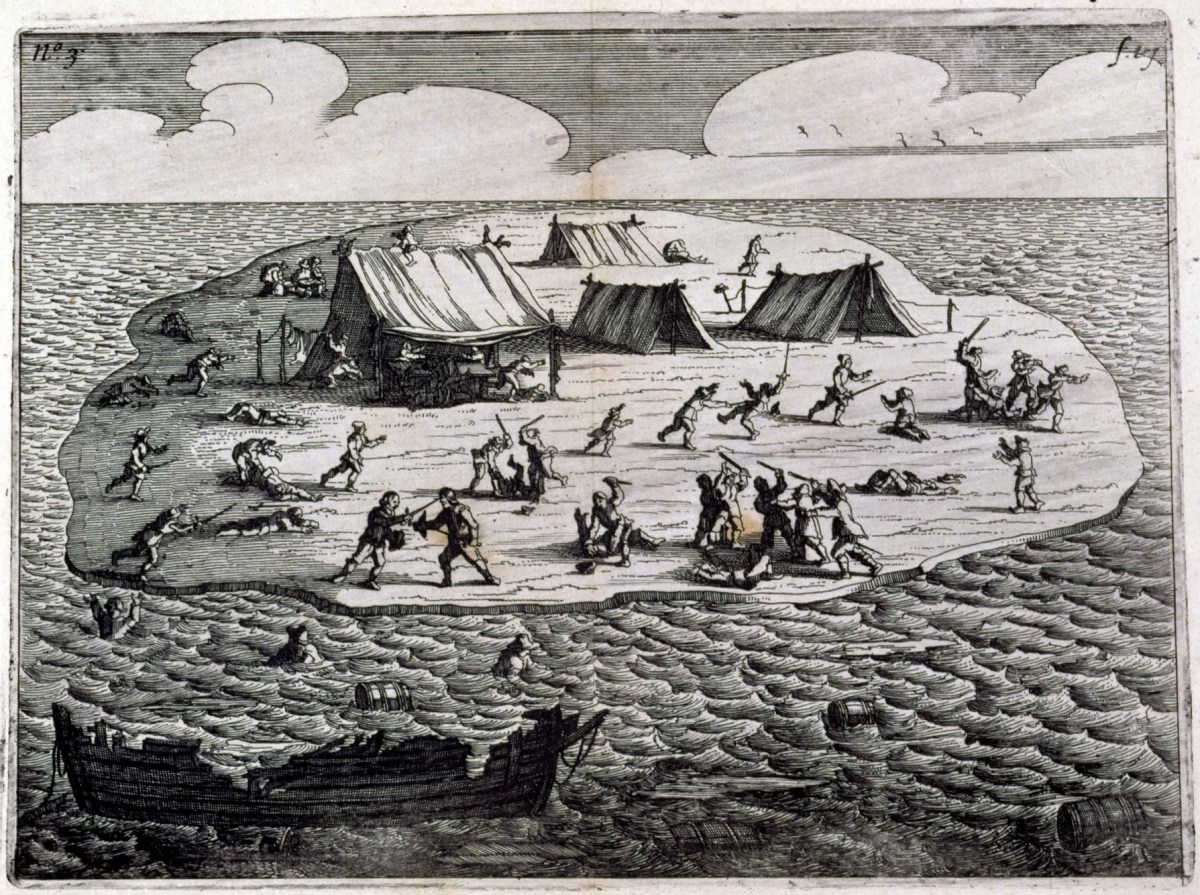

The women and children of Oradour-sur-Glane were locked in a church while German soldiers looted the town. The men were taken to a half-dozen barns and sheds where machine guns were already set up.

SS soldiers aimed for the legs when they opened fire, intending to inflict as much pain as possible. Five escaped in the confusion before Nazis lit the barn on fire. 190 men were burned alive.

Soldiers then lit an incendiary device in the church and gunned down 247 women and 205 children, as they fled for their lives.

47-year-old Marguerite Rouffanche escaped out a back window, followed by a young woman and child. All three were shot. Rouffanche alone escaped alive, crawling to some bushes where she managed to hide, until the next morning.

642 inhabitants of Oradour-sur-Glane, aged one week to 90 years, were shot to death, burned alive or some combination of the two, in just a few hours. The village was then razed to the ground.

Raymond J. Murphy, a 20-year-old American B-17 navigator shot down over France and hidden by the French Resistance, reported seeing a baby. The child had been crucified.

After the war, a new village was built on a nearby site. French President Charles de Gaulle ordered that the old village remain as it stood, a monument for all time to criminally insane governing ideologies, and the malign influence of collectivist thinking.

Generals Erwin Rommel and Walter Gleiniger, German commander in Limoges, protested the senseless act of brutality. Even the SS Regimental commander agreed and began an investigation, but it didn’t matter. Diekmann and most of the men who had carried out the massacre were themselves dead within the next few days, killed in combat.

The ghost village at the old Oradour-sur-Glane stands mute witness to this day, to the savagery committed by black-clad Schutzstaffel units in countless places like the French towns of Tulle, Ascq, Maillé, Robert-Espagne, and Clermont-en-Argonne; the Polish villages of Michniów, Wanaty and Krasowo-Częstki and the city of Warsaw; the Soviet village of Kortelisy; the Lithuanian village of Pirčiupiai; the Czechoslovakian villages of Ležáky and Lidice; the Greek towns of Kalavryta and Distomo; the Dutch town of Putten; the Yugoslavian towns of Kragujevac and Kraljevo and the village of Dražgoše, in what is now Slovenia; the Norwegian village of Telavåg; the Italian villages of Sant’Anna di Stazzema and Marzabotto.

And on. And on. And on.

The story was featured on the 1974 British television series “The World at War” narrated by Sir Laurence Olivier, who intones these words for the first and final episodes of the program:

“Down this road, on a summer day in 1944. . . The soldiers came. Nobody lives here now. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years. . . was dead. This is Oradour-sur-Glane, in France. The day the soldiers came, the people were gathered together. The men were taken to garages and barns, the women and children were led down this road . . . and they were driven. . . into this church. Here, they heard the firing as their men were shot. Then. . . they were killed too. A few weeks later, many of those who had done the killing were themselves dead, in battle. They never rebuilt Oradour. Its ruins are a memorial. Its martyrdom stands for thousands upon thousands of other martyrdoms in Poland, in Russia, in Burma, in China, in a World at War”.

Sir Laurence Olivier

French President Jacques Chirac dedicated a memorial museum in 1999, the “Centre de la mémoire d’Oradour“. The village stands today as those Nazi soldiers left it, seventy-seven years ago today.

It may be the most forlorn place on earth.

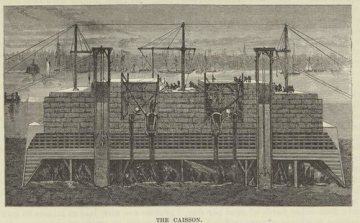

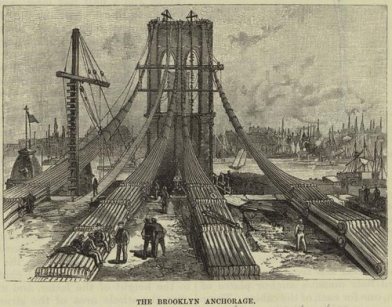

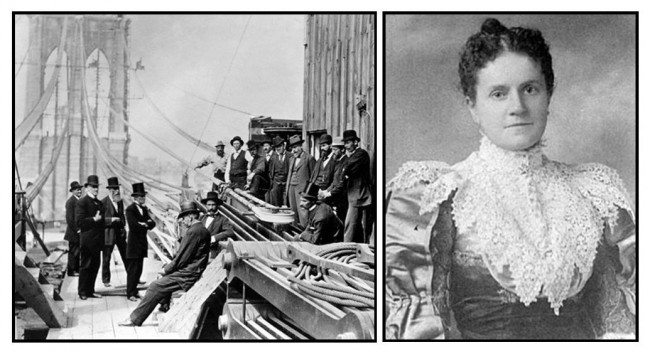

“Lockjaw” is such a sterile term, it doesn’t begin to describe the condition known as Tetanus. In the early stages, the anaerobic bacterium Clostridium Tetani produces tetanospasmin, a neurotoxin producing mild spasms in the jaw muscles. As the disease progresses, sudden and involuntary contractions affect skeletal muscle groups, becoming so powerful that bones are literally fractured as the muscles tear themselves apart. These were the last days of John Roebling, the bridge engineer who would not live to see his most famous work.

“Lockjaw” is such a sterile term, it doesn’t begin to describe the condition known as Tetanus. In the early stages, the anaerobic bacterium Clostridium Tetani produces tetanospasmin, a neurotoxin producing mild spasms in the jaw muscles. As the disease progresses, sudden and involuntary contractions affect skeletal muscle groups, becoming so powerful that bones are literally fractured as the muscles tear themselves apart. These were the last days of John Roebling, the bridge engineer who would not live to see his most famous work.

Murder charges were filed in both New York and New Jersey, but neither went to trial.

Murder charges were filed in both New York and New Jersey, but neither went to trial.

You must be logged in to post a comment.