Since the time of the Revolution, conflicts arose between those supporting a strong federal government, and those favoring greater self-determination for the states. In the South, climate conditions led to dependence on agriculture, the rural economy of the southern states producing cotton, rice, sugar, indigo and tobacco. Colder states to the north tended to develop manufacturing economies, urban centers growing up in service to hubs of transportation and the production of manufactured goods.

In the first half of the 19th century, 90% of federal government revenue came from tariffs on foreign manufactured goods. Most of this revenue was collected in the South, with the region’s greater dependence on imported goods. Much of this federal largesse was spent in the North, with the construction of roads, canals and other infrastructure.

The debate over economic issues and rights of self-determination, so-called ‘state’s rights’, grew and sharpened in 1828 with the threatened secession of South Carolina and the “nullification crisis” of 1832-33, when South Carolina declared such tariffs unconstitutional and therefore null and void within the state. Encyclopedia Britannica includes a Cartoon from the time depicting “Northern domestic manufacturers getting fat at the expense of impoverishing the South under protective tariffs.”

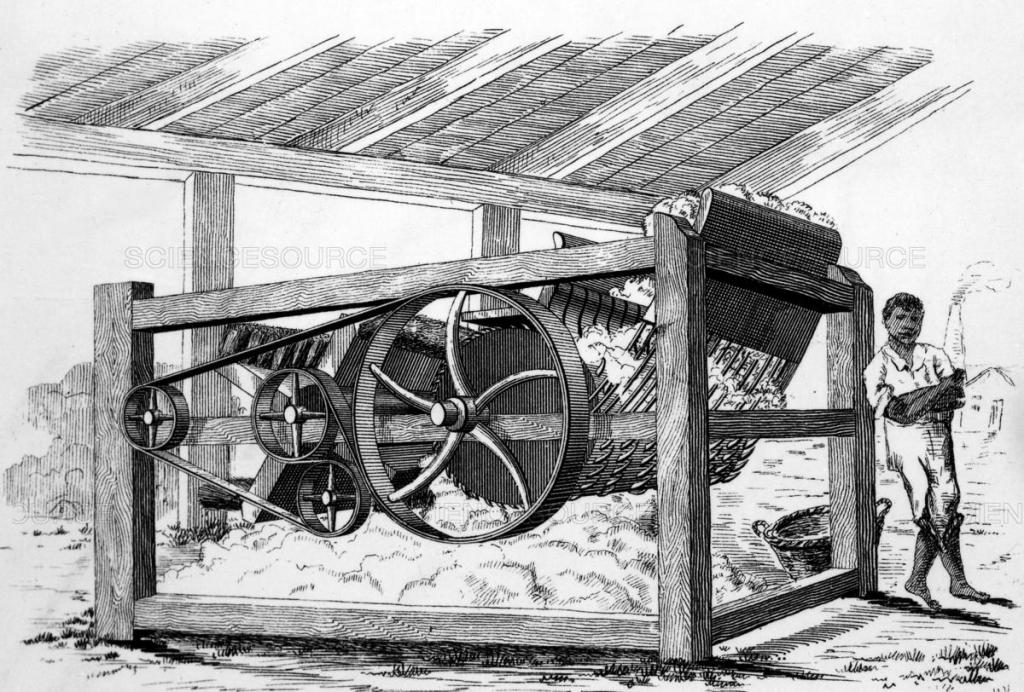

Chattel slavery existed from the earliest days of the colonial era, from Canada to Mexico, and around the world. Moral objections to what was really a repugnant practice could be found throughout, but economic forces had as much to do with ending the practice, as any other. The “peculiar institution” died out first in the colder regions of the US and may have done so in warmer climes as well, but for Eli Whitney’s invention of a cotton engine (‘gin’) in 1792.

It takes ten man-hours to remove the seeds to produce a single pound of cotton. By comparison, a cotton gin can process about a thousand pounds a day, at comparatively little expense.

The year of Whitney’s invention, the South exported 138,000 pounds a year to Europe and the northern colonies. Sixty years later, Britain alone was importing 600 million pounds a year, from the American south. Cotton was King, and with good reason. The stuff is easily grown, is more easily transportable, and can be stored indefinitely, compared with food crops. The southern economy turned overwhelmingly to this one crop and its need for plentiful, cheap labor. The issue of slavery had joined and become so intertwined with ideas of self-determination, as to be indistinguishable.

The first half of the 19th century was one of westward expansion in the United States, generating frequent and sharp conflicts between pro and anti-slavery factions. The Missouri compromise of 1820 was the first attempt to reconcile these factions, defining which territories would be slave states, and which would be “free”.

The short-lived “Wilmot Proviso” of 1846 sought to ban slavery in new territories, after which the Compromise of 1850 attempted to strike a balance. The Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854 created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, basically repealing the Missouri Compromise and allowing settlers to determine their own way through popular sovereignty.

This attempt to democratize the issue instead had the effect of drawing up battle lines. Pro-slavery forces established a territorial capital in Lecompton, while “antis” set up an alternative government in Topeka.

In Washington, Republicans backed the anti-slavery forces, while Democrats generally supported their opponents. The resulting standoff would soon escalate to violence. Upwards of a hundred or more would be killed between 1854 – 1861, in a period called “Bleeding Kansas”.

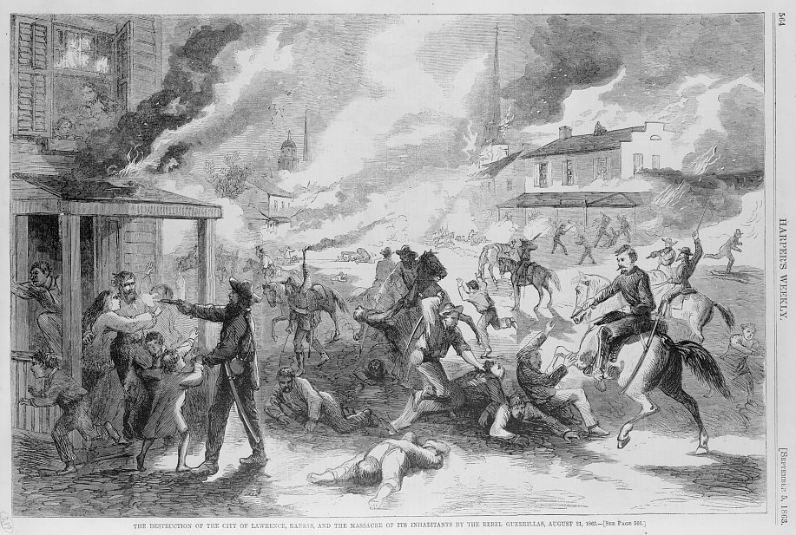

The town of Lawrence, Kansas was established by anti-slavery settlers in 1854, and soon became the focal point of pro-slavery violence. Emotions were at the boiling point when Douglas County Sheriff Samuel Jones was shot trying to arrest free-state settlers on April 23, 1856. Jones was driven out of town but he would return.

On this day in 1856, a posse of 800 pro-slavery forces closed around the town, led by Sheriff Jones. Cannon were positioned to cover the town and detachments of troops posted, to prevent escape. They commandeered the home of the first governor of Kansas, Charles L. Robinson, and used it as their headquarters.

The town’s two printing offices were sacked, the presses destroyed, and the type thrown into the river. The posse next set about to destroy the Free State Hotel, which they believed had been built to serve more as a fort than a hotel.

They may have been right, because it took the entire day with cannon shot, kegs of gunpowder and incendiary devices, before the hotel was finally reduced to a roofless, smoldering ruin.

There was looting and a few robberies as the men left town, burning Robinson’s home on the way out. Seven years later, a second raid on Lawrence resulted in the murder of over 150 boys and men. For now there was only one fatality: That of a slavery proponent killed, by falling masonry.

In the following days, five unarmed men will be taken from their homes and butchered with broadswords, by anti-slavery radicals John Brown, his sons and allies. Four months of partisan violence ensued when small armies formed up across eastern Kansas, clashing at places like Black Jack, Franklin, Fort Saunders, Hickory Point, Slough Creek, and Osawatomie

In Washington DC, a Senator will be beaten nearly to death on the floor of the United States Senate, by a member of the House of Representatives.

The 80-year-old nation forged inexorably onward, to a Civil War which would kill more Americans than every conflict from the American Revolution to the War on Terror, combined.

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

LikeLike