Similar to the Base Exchange system serving American military personnel, the British Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) is the UK-government organization operating clubs, bars, shops and supermarkets in service to British armed forces, as well as naval canteen services (NCS) on board Royal Navy ships.

NAAFI personnel serving on ships are assigned to duty stations and wear uniforms, while technically remaining civilians.

Tommy Brown was fifteen when he lied about his age, enlisting in the NAAFI and assigned as canteen assistant to the “P-class” destroyer, HMS Petard.

On October 30, 1942, Petard joined three other destroyers and a squadron of Vickers Wellesley light bombers off the coast of Port Said Egypt, in a 16-hour hunt for the German “Unterseeboot”, U–559.

Hours of depth charge attacks were rewarded when the crippled U-559 came to the surface, the 4-inch guns of HMS Petard, permanently ending the career of the German sub.

The crew abandoned ship, but not before opening the boat’s seacocks. Water was pouring into the submarine as Lieutenant Francis Anthony Blair Fasson and Able Seaman Colin Grazier dived into the water and swam to the submarine, with junior canteen assistant Tommy Brown close behind.

With U-559 sinking fast, Fasson and Grazier made their way into the captain’s cabin. Finding a set of keys, Fasson opened a drawer, to discover a number of documents, including two sets of code books.

With one hand on the conning ladder and the other clutching those documents, Brown made three trips up and down through the hatch, to Petard’s whaler.

In the final moments, the ship’s cook called for his shipmates to get out of the boat. Brown himself was dragged under, but managed to kick free and come to the surface. Colin Grazier and Francis Fasson, went down with the German sub.

The episode brought Brown to the attention of the authorities, ending his posting aboard Petard when his true age became known. He was not discharged from the NAAFI, and later returned to sea on board the light cruiser, HMS Belfast.

In 1945, now-Leading Seaman Tommy Brown was home on shore leave, when fire broke out at the family home in South Shields. He died while trying to rescue his 4-year-old sister Maureen, and was buried with full military honors in Tynemouth cemetery.

Fasson and Grazier were awarded the George Cross, the second-highest award in the United Kingdom system of honors. Since he was a civilian due to his NAAFI employment, Brown was awarded the George Medal.

For German U-boat commanders, the period between the fall of France and the American entry into WW2 was known as “Die Glückliche Zeit” – “The Happy Time” – in the North Sea and North Atlantic. From July through October 1940 alone, 282 Allied ships were sunk on the approaches to Ireland, for a combined loss of 1.5 million tons of merchant shipping.

For German U-boat commanders, the period between the fall of France and the American entry into WW2 was known as “Die Glückliche Zeit” – “The Happy Time” – in the North Sea and North Atlantic. From July through October 1940 alone, 282 Allied ships were sunk on the approaches to Ireland, for a combined loss of 1.5 million tons of merchant shipping.

Tommy Brown’s Mediterranean episode took place in 1942, in the midst of the “Second Happy Time”, a period known among German submarine commanders as the “American shooting season”. U-boats inflicted massive damage during this period, sinking 609 ships totaling 3.1 million tons with the loss of thousands of lives, against a cost of only 22 U-boats.

USMM.org reports that the United States Merchant Marine service suffered a higher percentage of fatalities at 3.9%, than any American service branch in WW2.

Early versions of the German “Enigma” code were broken as early as 1932, thanks to cryptanalysts of the Polish Cipher Bureau, and French spy Hans Thilo Schmidt. French and British military intelligence were read into Polish decryption techniques in 1939, these methods later improved upon by the British code breakers of Bletchley Park.

Early versions of the German “Enigma” code were broken as early as 1932, thanks to cryptanalysts of the Polish Cipher Bureau, and French spy Hans Thilo Schmidt. French and British military intelligence were read into Polish decryption techniques in 1939, these methods later improved upon by the British code breakers of Bletchley Park.

Vast numbers of messages were intercepted and decoded from Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe sources through the Allied intelligence project “Ultra”, shortening the war by at least a year, and possibly two.

The Kriegsmarine was a different story. Maniacally concerned with security, Admiral Karl Dönitz introduced a third-generation enigma machine (M4) into the submarine service around May 1941, a system so secret that neither Wehrmacht nor Luftwaffe, were aware of its existence.

The system requires identical cipher machines at both ends of the transmission and took a while to put into place, with German subs being spread around the world.

All M4 machines were distributed by early 1942. On February 2, German submarine communications went dark. For code breakers at Bletchley Park, the blackout was sudden and complete. For a period of nine months, Allies had not the slightest idea of what the German submarine service was up to. The result was catastrophic.

All M4 machines were distributed by early 1942. On February 2, German submarine communications went dark. For code breakers at Bletchley Park, the blackout was sudden and complete. For a period of nine months, Allies had not the slightest idea of what the German submarine service was up to. The result was catastrophic.

U-559 documents were rushed back to England, arriving at Bletchley Park on November 24, allowing cryptanalysts to attack the “Triton” key used within the U-boat service. It would not be long, before the U-boats themselves were under attack.

The M4 code was broken by December 13, when the first of a steady stream of intercepts arrived at the Admiralty Operational Intelligence Office, giving the positions of 12 U-boats.

The UK Guardian newspaper wrote: “The naval historian Ralph Erskine thinks that, without the (M4) breakthrough, the Normandy invasion would have been delayed by at least a year, and that between 500,000 and 750,000 tons of allied shipping were saved in December 1942 and January 1943 alone”.

Tommy Brown never knew what was in those documents. The entire enterprise would remain Top Secret, until decades after he died.

Winston Churchill later wrote, that the actions of the crew of HMS Petard were “crucial to the outcome of the war”.

Untold numbers of lives that could have been lost. But for the actions, of a sixteen-year-old ship’s cook.

Japanese forces invaded China in the summer of 1937, advancing on Nanking as American citizens evacuated the city. The last of them boarded Panay on December 11: five officers, 54 enlisted men, four US embassy staff, and 10 civilians.

Japanese forces invaded China in the summer of 1937, advancing on Nanking as American citizens evacuated the city. The last of them boarded Panay on December 11: five officers, 54 enlisted men, four US embassy staff, and 10 civilians. The matter was officially settled four months later, with an official apology and an indemnity of $2,214,007.36 paid to the US government.

The matter was officially settled four months later, with an official apology and an indemnity of $2,214,007.36 paid to the US government.

In 1928, Al Capone purchased a Cadillac 341A Town Sedan with 3,000 pounds of armor and inch-thick bulletproof windows. It was green and black, matching the Chicago police cars of the era, and equipped with a siren and flashing lights hidden behind the grill.

In 1928, Al Capone purchased a Cadillac 341A Town Sedan with 3,000 pounds of armor and inch-thick bulletproof windows. It was green and black, matching the Chicago police cars of the era, and equipped with a siren and flashing lights hidden behind the grill.

The internet can be a wonderful thing, if you don’t mind taking your water from a fire hose. The reader of history quickly finds that some tales are true as written, some are not, and some stories are so good you want them to be true.

The internet can be a wonderful thing, if you don’t mind taking your water from a fire hose. The reader of history quickly finds that some tales are true as written, some are not, and some stories are so good you want them to be true.

For Imperial Japan, Yamamoto’s worst nightmare would prove correct. In terms of GDP, the Tokyo government had attacked an adversary, nearly six times its own size. The Japanese economy reached its high point in 1942 and declined steadily throughout the war years, while that of the United States exploded at a rate unseen in human history.

For Imperial Japan, Yamamoto’s worst nightmare would prove correct. In terms of GDP, the Tokyo government had attacked an adversary, nearly six times its own size. The Japanese economy reached its high point in 1942 and declined steadily throughout the war years, while that of the United States exploded at a rate unseen in human history.

Lieutenant Commander Joseph O’Callahan, a Jesuit priest from Boston and former Holy Cross track star was a Chaplain aboard the Franklin. O’Callahan was everywhere, hurling bombs overboard and administering last rites, shouting encouragement and fighting fires. Father O’Callahan would be the only Chaplain of WW2, to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

Lieutenant Commander Joseph O’Callahan, a Jesuit priest from Boston and former Holy Cross track star was a Chaplain aboard the Franklin. O’Callahan was everywhere, hurling bombs overboard and administering last rites, shouting encouragement and fighting fires. Father O’Callahan would be the only Chaplain of WW2, to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

Construction began in March as trains moved hundreds of pieces of construction equipment to Dawson Creek, the last stop on the Northern Alberta Railway. At the other end, 10,670 American troops arrived in Alaska that spring, to begin what their officers called “the biggest and hardest job since the Panama Canal.”

Construction began in March as trains moved hundreds of pieces of construction equipment to Dawson Creek, the last stop on the Northern Alberta Railway. At the other end, 10,670 American troops arrived in Alaska that spring, to begin what their officers called “the biggest and hardest job since the Panama Canal.” The project had a new sense of urgency in June, when Japanese forces landed on Kiska and Attu Islands, in the Aleutian chain. Adding to that urgency was that there is no more than an eight month construction window, before the return of the deadly Alaskan winter.

The project had a new sense of urgency in June, when Japanese forces landed on Kiska and Attu Islands, in the Aleutian chain. Adding to that urgency was that there is no more than an eight month construction window, before the return of the deadly Alaskan winter. Engines had to run around the clock, as it was impossible to restart them in the cold. Engineers waded up to their chests building pontoons across freezing lakes, battling mosquitoes in the mud and the moss laden arctic bog. Ground that had been frozen for thousands of years was scraped bare and exposed to sunlight, creating a deadly layer of muddy quicksand in which bulldozers sank in what seemed like stable roadbed.

Engines had to run around the clock, as it was impossible to restart them in the cold. Engineers waded up to their chests building pontoons across freezing lakes, battling mosquitoes in the mud and the moss laden arctic bog. Ground that had been frozen for thousands of years was scraped bare and exposed to sunlight, creating a deadly layer of muddy quicksand in which bulldozers sank in what seemed like stable roadbed.

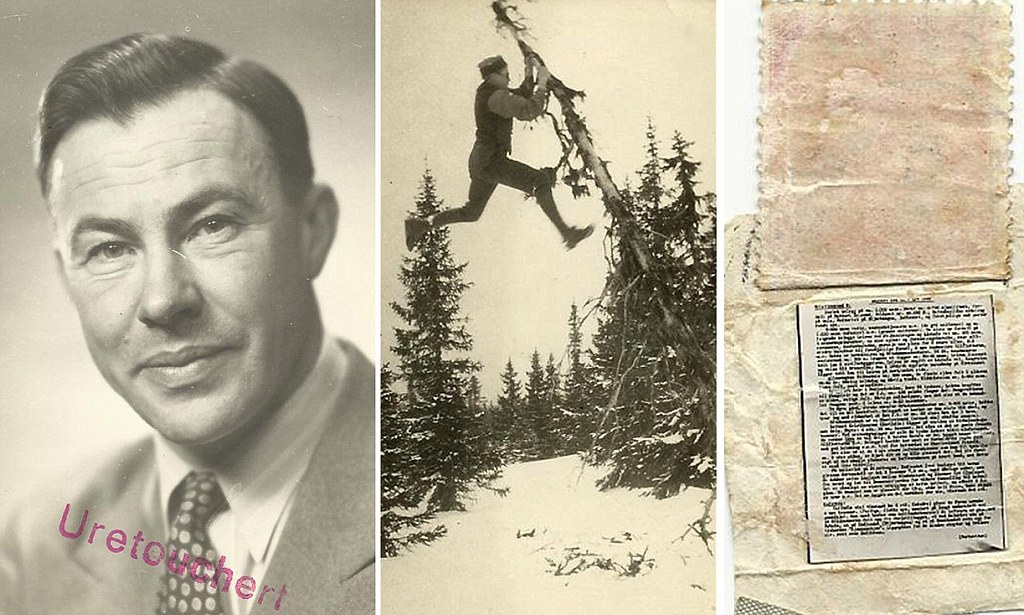

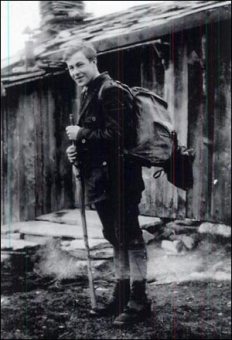

Another such man was his brother Sven, born this day, November 19, 1904.

Another such man was his brother Sven, born this day, November 19, 1904. The Norwegian had barely an hour’s head start, and the Nazis couldn’t let this guy get away. He knew too much. Somme was pursued through streams and ravines as he worked his way into the mountains.

The Norwegian had barely an hour’s head start, and the Nazis couldn’t let this guy get away. He knew too much. Somme was pursued through streams and ravines as he worked his way into the mountains. Somme finally made it to neutral Sweden, where he was taken to England. There he met the exiled King of Norway, and the woman who would one day become his wife and mother of his three daughters, an English woman named Primrose.

Somme finally made it to neutral Sweden, where he was taken to England. There he met the exiled King of Norway, and the woman who would one day become his wife and mother of his three daughters, an English woman named Primrose.

Born on October 29, 1921 in New Mexico and brought up in Arizona, William Henry “Bill” Mauldin was part of what Tom Brokaw called, the “Greatest Generation”.

Born on October 29, 1921 in New Mexico and brought up in Arizona, William Henry “Bill” Mauldin was part of what Tom Brokaw called, the “Greatest Generation”. Mauldin developed two cartoon infantrymen, calling them “Willie and Joe”. He told the story of the war through their eyes. He became extremely popular within the enlisted ranks, while his humor tended to poke fun at the “spit & polish” of the officer corps. He even lampooned General George Patton one time, for insisting that his men to be clean shaven all the time. Even in combat.

Mauldin developed two cartoon infantrymen, calling them “Willie and Joe”. He told the story of the war through their eyes. He became extremely popular within the enlisted ranks, while his humor tended to poke fun at the “spit & polish” of the officer corps. He even lampooned General George Patton one time, for insisting that his men to be clean shaven all the time. Even in combat. Mauldin later told an interviewer, “I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn’t like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes”.

Mauldin later told an interviewer, “I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn’t like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes”. Bill Mauldin drew Willie & Joe for last time in 1998, for inclusion in Schulz’ Veteran’s Day Peanuts strip. Schulz had long described Mauldin as his hero. He signed that final strip Schulz, as always, and added “and my Hero“. Bill Mauldin’s signature, appears underneath.

Bill Mauldin drew Willie & Joe for last time in 1998, for inclusion in Schulz’ Veteran’s Day Peanuts strip. Schulz had long described Mauldin as his hero. He signed that final strip Schulz, as always, and added “and my Hero“. Bill Mauldin’s signature, appears underneath.

The diary tells of a respect this man had for “Captain Boeing”. Beaten almost senseless, his arms tied so tightly that his elbows touched behind his back, Captain Pease was driven to his knees in the last moments of his life. Knowing he was about to die, Harl Pease uttered the most searing insult possible against an expert swordsman and self-styled “samurai”. Particularly one with such a helpless victim. It was the single word, in Japanese. “Once!“.

The diary tells of a respect this man had for “Captain Boeing”. Beaten almost senseless, his arms tied so tightly that his elbows touched behind his back, Captain Pease was driven to his knees in the last moments of his life. Knowing he was about to die, Harl Pease uttered the most searing insult possible against an expert swordsman and self-styled “samurai”. Particularly one with such a helpless victim. It was the single word, in Japanese. “Once!“.

Once, the small dog was able to perform a task in minutes that otherwise would have taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire. The air field at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, was crucial to the Allied war effort, and the signal corps needed to run a telegraph wire across the field. A 70′ long, 8” pipe crossed underneath the air strip, half filled with dirt.

Once, the small dog was able to perform a task in minutes that otherwise would have taken an airstrip out of service for three days, and exposed an entire construction battalion to enemy fire. The air field at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, was crucial to the Allied war effort, and the signal corps needed to run a telegraph wire across the field. A 70′ long, 8” pipe crossed underneath the air strip, half filled with dirt. Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and entertaining thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s considered to be the first therapy dog, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed.

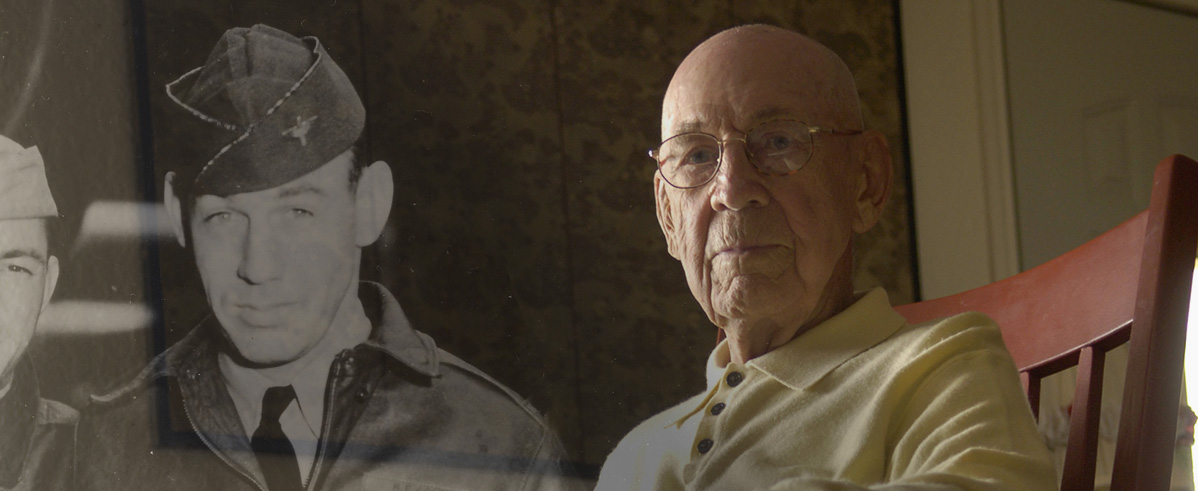

Smoky toured all over the world after the war, appearing in over 42 television programs and entertaining thousands at veteran’s hospitals. In June 1945, Smoky toured the 120th General Hospital in Manila, visiting with wounded GIs from the Battle of Luzon. She’s considered to be the first therapy dog, and credited with expanding interest in what had hitherto been an obscure breed. Bill Wynne was 90 years old in 2012, when he was “flabbergasted” to be approached by Australian authorities. They explained that an Australian army nurse had purchased the dog from a Queen Street pet store, becoming separated in the jungles of New Guinea. 68 years later, the Australians had come to award his dog a medal.

Bill Wynne was 90 years old in 2012, when he was “flabbergasted” to be approached by Australian authorities. They explained that an Australian army nurse had purchased the dog from a Queen Street pet store, becoming separated in the jungles of New Guinea. 68 years later, the Australians had come to award his dog a medal.

You must be logged in to post a comment.