On May 10, 1915, President Woodrow Wilson gave what came to be known as his “Too Proud to Fight Speech” in which he said: “The example of America must be the example not merely of peace because it will not fight, but of peace because peace is the healing and elevating influence of the world and strife is not. There is such a thing as a man being so right it does not need to convince others by force that it is right”.

Though Wilson didn’t mention it directly, HMS Lusitania had been torpedoed only three days earlier with the loss of 1,198, 128 of whom were Americans.

Though Wilson didn’t mention it directly, HMS Lusitania had been torpedoed only three days earlier with the loss of 1,198, 128 of whom were Americans.

No one doubted that the attack on the civilian liner was foremost on the President’s mind. Back in February, Imperial Germany had declared a naval blockade against Great Britain, warning that “On and after February 18th every enemy merchant vessel found in this region will be destroyed, without its always being possible to warn the crews or passengers of the dangers threatening“. “Neutral ships” the announcement continued, “will also incur danger in the war region“.

The reaction to the Lusitania sinking was immediate and vehement, portraying the attack as the act of barbarians and huns and demanding a German return to “prize rules”, requiring submarines to surface and search merchantmen while placing crews and passengers in “a place of safety”.

The reaction to the Lusitania sinking was immediate and vehement, portraying the attack as the act of barbarians and huns and demanding a German return to “prize rules”, requiring submarines to surface and search merchantmen while placing crews and passengers in “a place of safety”.

Imperial Germany protested that Lusitania was fair game, as she was illegally transporting munitions intended to kill German boys on European battlefields. Furthermore, the embassy pointed out that ads had been taken out in the New York Times and other newspapers, specifically warning that the liner was subject to attack.

Nevertheless, the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare was suspended for a time, for fear of bringing the US into the war against Germany.

President Wilson was elected back in 1912, talking about the sort of agrarian utopia favored by Thomas Jefferson. In 1916, the election was about war and peace. Wilson won re-election on the slogan “He kept us out of war”, but it hadn’t been easy. In Europe, WWI was in its second year while, to our south, Mexico was going through a full-blown revolution. Public opinion had shifted in favor of England and France by this time. The German resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, threatened to tip the balance.

With Great Britain holding naval superiority on the surface, Germany had to do something to starve the British war effort. In early 1917, chief of the Admiralty Staff Admiral Henning von Holtzendorff argued successfully for the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, the policy to take effect on February 1.

Anticipating the results of such a move, German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann dispatched a telegram to German ambassador to Mexico Heinrich von Eckardt on January 19, authorizing the ambassador to propose a military alliance with Mexico, in the event of American entry into the war. “We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona”.

The American cargo vessel SS Housatonic was stopped off the southwest coast of England on February 3, and boarded by German submarine U-53. Captain Thomas Ensor was interviewed by Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, who explained he was sorry, but Housatonic was “carrying food supplies to the enemy of my country”. She would be destroyed. The American Captain and crew were allowed to launch lifeboats and abandon ship, while German sailors raided the American’s soap supplies. Apparently, WWI-vintage German subs were short on soap.

The American cargo vessel SS Housatonic was stopped off the southwest coast of England on February 3, and boarded by German submarine U-53. Captain Thomas Ensor was interviewed by Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, who explained he was sorry, but Housatonic was “carrying food supplies to the enemy of my country”. She would be destroyed. The American Captain and crew were allowed to launch lifeboats and abandon ship, while German sailors raided the American’s soap supplies. Apparently, WWI-vintage German subs were short on soap.

Housatonic was sunk with a single torpedo, the U-Boat towing the now-stranded Americans toward the English coast. Sighting the trawler Salvator, Rose fired his deck guns to be sure they’d been spotted, and then slipped away. It was February 3, 1917.

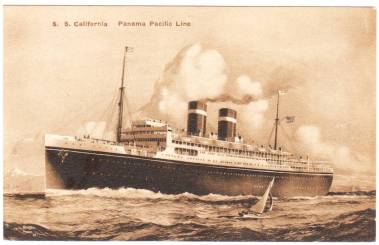

President Woodrow Wilson retaliated, breaking off diplomatic relations with Germany the following day. Three days later, a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California, off the Irish coast. One missed, but the second tore into the port side of the 470-foot, 9,000-ton steamer. California sank in nine minutes, killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew.

President Woodrow Wilson retaliated, breaking off diplomatic relations with Germany the following day. Three days later, a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California, off the Irish coast. One missed, but the second tore into the port side of the 470-foot, 9,000-ton steamer. California sank in nine minutes, killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew.

In Mexico, a military commission convened by President Venustiano Carranza quickly concluded that the German proposal was unviable, but the damage was done. British code breakers intercepted the Zimmermann telegram, divulging the contents to the American government on February 24.

The contents of Zimmermann’s note were published in the American media on March 1. Even then, there was considerable antipathy toward the British side, particularly among Americans of German and Irish ethnicity. “Who says this thing is genuine, anyway”, they might have said. “Maybe it’s a British forgery”.

The contents of Zimmermann’s note were published in the American media on March 1. Even then, there was considerable antipathy toward the British side, particularly among Americans of German and Irish ethnicity. “Who says this thing is genuine, anyway”, they might have said. “Maybe it’s a British forgery”.

Zimmermann himself put an end to such speculation two days later, telling an American journalist, “I cannot deny it. It is true.” What Zimmermann had hoped that Americans would see as mere contingency, public opinion in the US saw as an unforgivable betrayal of American neutrality.

The combination of events was the last straw. Wilson’s War Cabinet voted unanimously for a declaration of war on March 20. The President himself delivered his war address before a joint session of Congress, two weeks later. The United States entered the “war to end all wars”, on April 6.

Afterward

At the time, the German claim that Lusitania carried contraband munitions seemed to be supported by survivors’ reports of secondary explosions within the stricken liner’s hull. In 2008, the UK Daily Mail reported that dive teams had reached the wreck, lying at a depth of 300′. Divers reported finding tons of US manufactured Remington .303 ammunition, about 4 million rounds, stored in unrefrigerated cargo holds in cases marked “Cheese”, “Butter”, and “Oysters”.

Parisian children made little good luck charms, as “protection” from the Paris gun. They were tiny pairs of handmade dolls, joined together by scraps of yarn. Their names were Nénette and Rintintin

Parisian children made little good luck charms, as “protection” from the Paris gun. They were tiny pairs of handmade dolls, joined together by scraps of yarn. Their names were Nénette and Rintintin US Army Air Service Corporal Lee Duncan was in Paris at this time, with the 135th Aero Squadron. Duncan was aware of the custom, he may even have been given such a talisman himself.

US Army Air Service Corporal Lee Duncan was in Paris at this time, with the 135th Aero Squadron. Duncan was aware of the custom, he may even have been given such a talisman himself.

Better known as “Strongheart”, Etzel appeared in silent films throughout the ’20s, becoming the first major canine film star and credited with enormously increasing the popularity of the breed.

Better known as “Strongheart”, Etzel appeared in silent films throughout the ’20s, becoming the first major canine film star and credited with enormously increasing the popularity of the breed.

On July 28, 1866, the Army Reorganization Act authorized the formation of 30 new units, including two cavalry and four infantry regiments “which shall be composed of colored men.”

On July 28, 1866, the Army Reorganization Act authorized the formation of 30 new units, including two cavalry and four infantry regiments “which shall be composed of colored men.” The original units fought in the American Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, the Border War and two World Wars, amassing 22 Medals of Honor by the end of WW1.

The original units fought in the American Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine-American War, the Border War and two World Wars, amassing 22 Medals of Honor by the end of WW1.

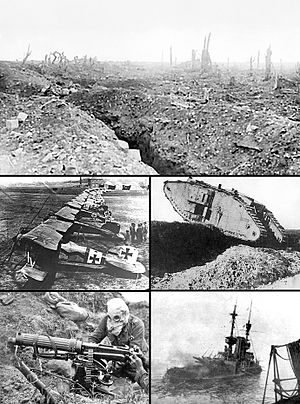

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers. German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”.

German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”. Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

A “Fidelity Medallion” was awarded to three militia men in 1780, for the capture of

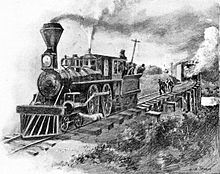

A “Fidelity Medallion” was awarded to three militia men in 1780, for the capture of  An Army version of the medal was created the following July, first awarded to six Union soldiers for hijacking the Confederate locomotive, “The General”. Leader of the raid James Andrews was caught and hanged as a Union spy. He alone was judged ineligible for the medal of honor, as he was a civilian.

An Army version of the medal was created the following July, first awarded to six Union soldiers for hijacking the Confederate locomotive, “The General”. Leader of the raid James Andrews was caught and hanged as a Union spy. He alone was judged ineligible for the medal of honor, as he was a civilian. Few soldiers on the Civil War battlefield had a quicker route to death’s door, than the color bearer. National and regimental flags were all-important sources of inspiration and communication.

Few soldiers on the Civil War battlefield had a quicker route to death’s door, than the color bearer. National and regimental flags were all-important sources of inspiration and communication.

Father

Father

There was strong sentiment at the time, that German sabotage lay behind the disaster. A front-page headline on the December 10 Halifax Herald Newspaper proclaimed “Practically All the Germans in Halifax Are to Be Arrested”.

There was strong sentiment at the time, that German sabotage lay behind the disaster. A front-page headline on the December 10 Halifax Herald Newspaper proclaimed “Practically All the Germans in Halifax Are to Be Arrested”.

This is no Charlie Brown shrub we’re talking about. The 1998 tree required 3,200 man-hours to decorate: 17,000 lights connected by 4½ miles of wire, and decorated with 8,000 bulbs.

This is no Charlie Brown shrub we’re talking about. The 1998 tree required 3,200 man-hours to decorate: 17,000 lights connected by 4½ miles of wire, and decorated with 8,000 bulbs.

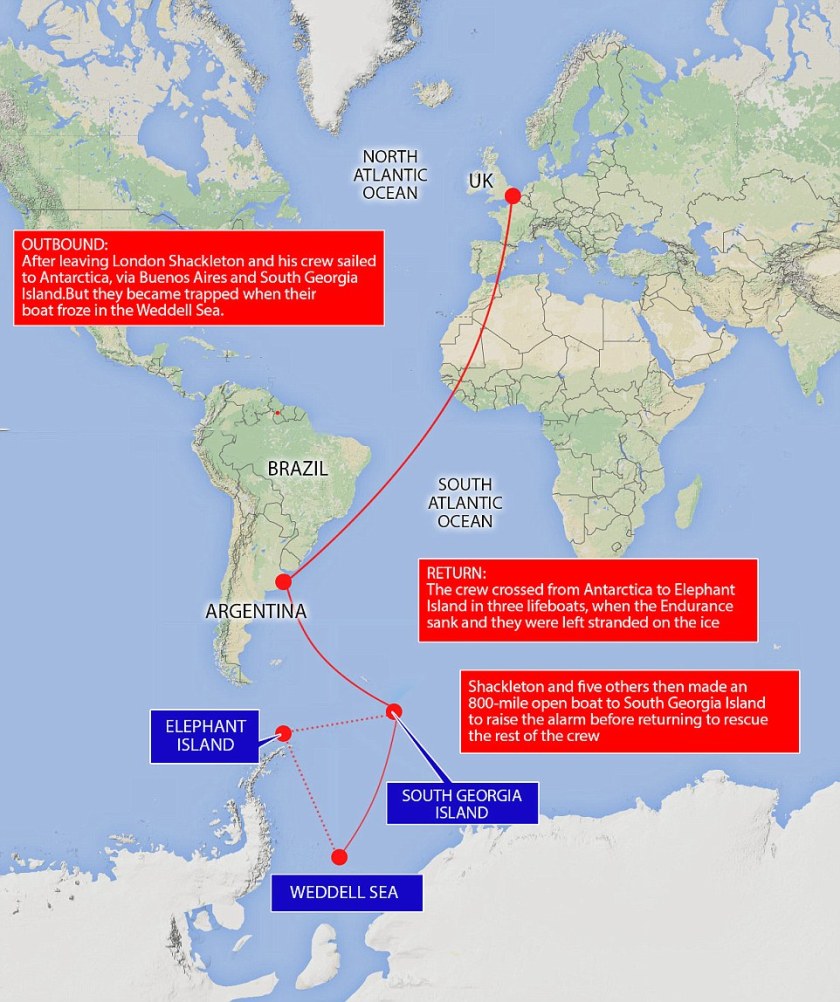

The trio arrived at the Stromness whaling station on May 20. They must have been a sight, with thick ice encrusting their long, filthy beards, and saltwater-soaked sealskin clothing rotting from their bodies. The first people they came across were children, who ran in fright at the sight of them.

The trio arrived at the Stromness whaling station on May 20. They must have been a sight, with thick ice encrusting their long, filthy beards, and saltwater-soaked sealskin clothing rotting from their bodies. The first people they came across were children, who ran in fright at the sight of them.

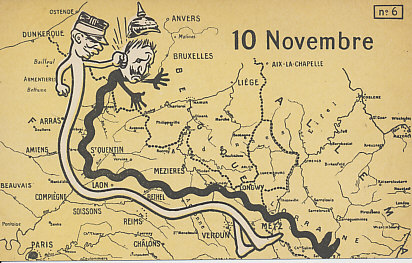

Imperial Germany, its army disintegrating in the field and threatened with revolution at home, had sent a peace delegation, headed by the 43-year-old German politician Matthias Erzberger.

Imperial Germany, its army disintegrating in the field and threatened with revolution at home, had sent a peace delegation, headed by the 43-year-old German politician Matthias Erzberger.

Foch informed Ertzberger that he had 72 hours in which to respond. “For God’s sake, Monsieur le Marechal”, responded the German, “do not wait for those 72 hours. Stop the hostilities this very day”. By this time, 2,250 were dying every day on the Western Front, yet the plea fell on deaf ears. Fighting would continue until the last minute of the last day.

Foch informed Ertzberger that he had 72 hours in which to respond. “For God’s sake, Monsieur le Marechal”, responded the German, “do not wait for those 72 hours. Stop the hostilities this very day”. By this time, 2,250 were dying every day on the Western Front, yet the plea fell on deaf ears. Fighting would continue until the last minute of the last day. At least 320 Americans were killed in those final six hours, 3,240 seriously wounded.

At least 320 Americans were killed in those final six hours, 3,240 seriously wounded. Matthias Erzberger was assassinated in 1921, for his role in the surrender. The “Stab in the Back” mythology destined to become Nazi propaganda, had already begun.

Matthias Erzberger was assassinated in 1921, for his role in the surrender. The “Stab in the Back” mythology destined to become Nazi propaganda, had already begun.

This invasion force, commanded by General Arthur Aitkin, spent that first day and most of the second sweeping for non-existent mines, before finally assembling an assault force on the beaches late on November 3rd. It was a welcome break for the German Commander, Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, who had assembled and trained a force of Askari warriors around a core of white German commissioned and non-commissioned officers.

This invasion force, commanded by General Arthur Aitkin, spent that first day and most of the second sweeping for non-existent mines, before finally assembling an assault force on the beaches late on November 3rd. It was a welcome break for the German Commander, Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, who had assembled and trained a force of Askari warriors around a core of white German commissioned and non-commissioned officers.

Colonel, and later General Lettow-Vorbeck, was called “

Colonel, and later General Lettow-Vorbeck, was called “ Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck came to loathe Adolf Hitler, and tried to establish a conservative opposition to the Nazi political machine. When offered the ambassadorship to the Court of St. James in 1935, he apparently did more than merely decline the job. He told Der Fuehrer to perform an anatomically improbable act. Years later, Charles Miller asked the nephew of a Schutztruppe officer about the exchange. “I understand that von Lettow told Hitler to go f**k himself”. “That’s right”Came the reply, “except that I don’t think he put it that politely”.

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck came to loathe Adolf Hitler, and tried to establish a conservative opposition to the Nazi political machine. When offered the ambassadorship to the Court of St. James in 1935, he apparently did more than merely decline the job. He told Der Fuehrer to perform an anatomically improbable act. Years later, Charles Miller asked the nephew of a Schutztruppe officer about the exchange. “I understand that von Lettow told Hitler to go f**k himself”. “That’s right”Came the reply, “except that I don’t think he put it that politely”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.