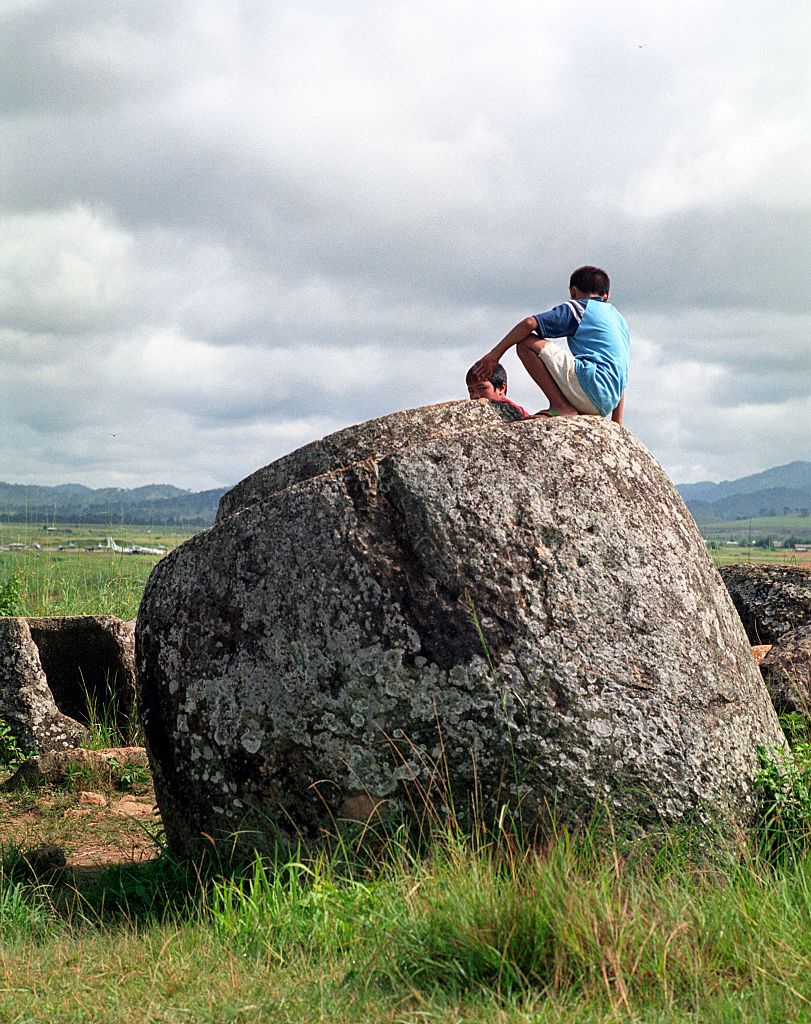

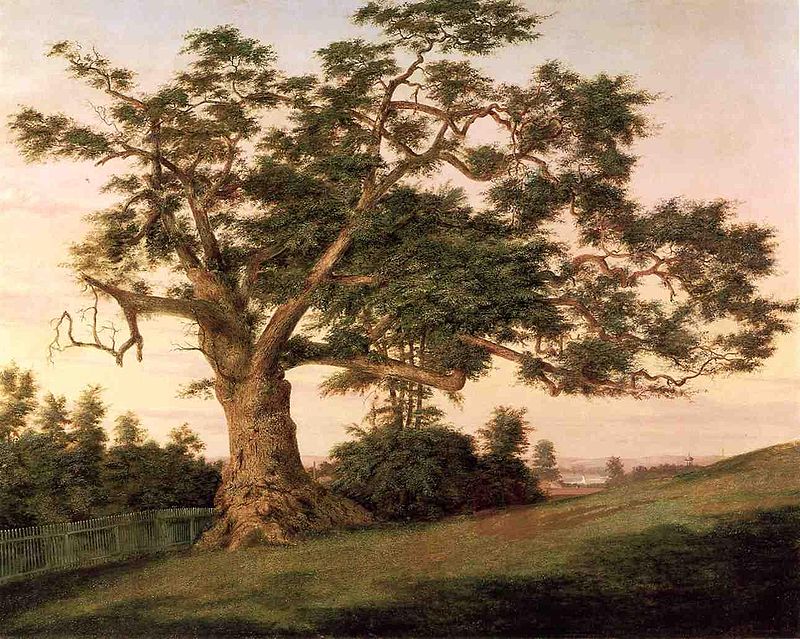

When George Washington raised his sword under the branches of that ancient elm on Cambridge commons, by that act did the General take command of an “army” equipped with an average of nine rounds, per man.

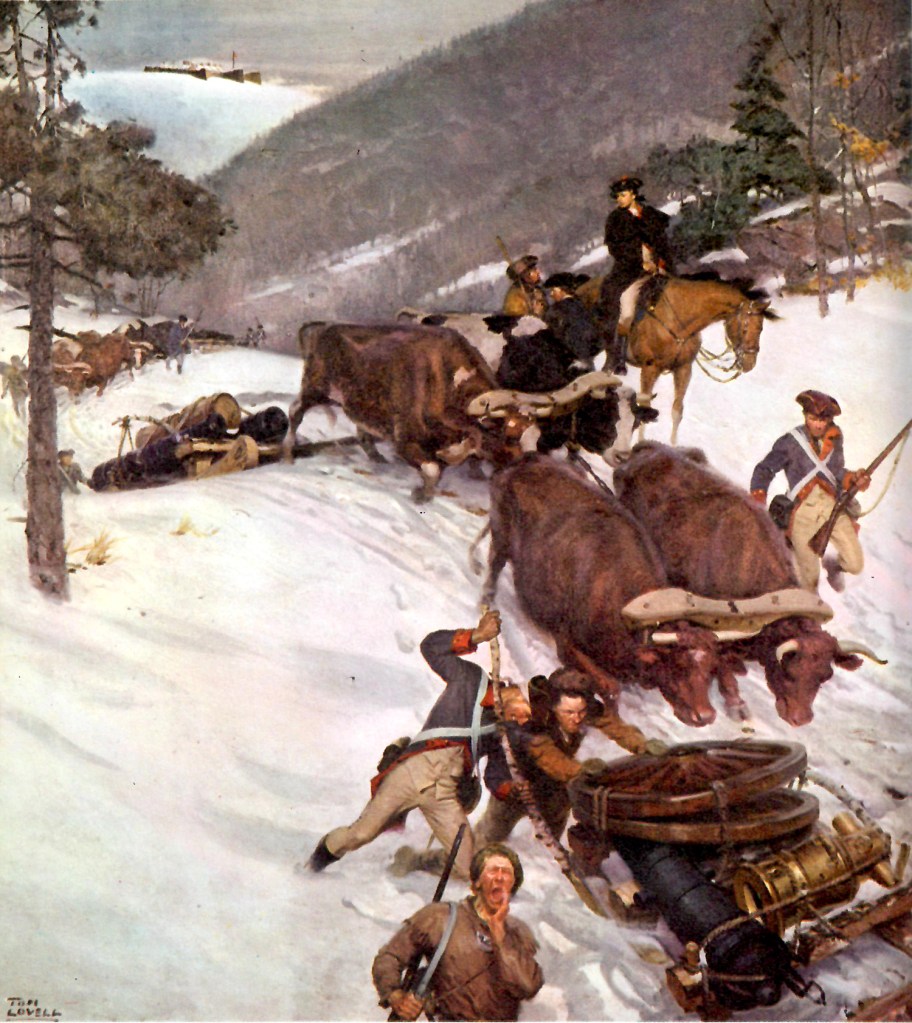

1776 started out well for the cause of American independence, when the twenty-six-year-old bookseller Henry Knox emerged from a six week slog through a New England winter, at the head of a “Noble train of artillery’. Manhandled all the way from the wilds of upstate New York, the guns of Fort Ticonderoga were wrestled to the top of Dorchester Heights, overlooking the British fleet anchored in Boston Harbor. General sir William Howe now faced the prospect of another Bunker Hill, a British victory which had come at a cost he could ill afford, to pay again.

The eleven-month siege of Boston came to an end on March 17 when Howe’s fleet evacuated Boston Harbor and removed, to Nova Scotia. Three months later, a force of some 400 South Carolina patriots fought a day-long battle with the nine warships of Admiral Sir Peter Parker, before the heavily damaged fleet was forced to withdraw. The British eventually captured Fort Moultrie and Charleston Harbor with it but, for now, 1776 was shaping up to be a very good year.

The Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, that July.

Tory and Patriot alike understood the strategic importance of New York, as the center of communication between the upper and lower colonies. Beginning that April, Washington moved his forces from Boston to New York placing his troops along the west end of Long Island, in anticipation of the British return.

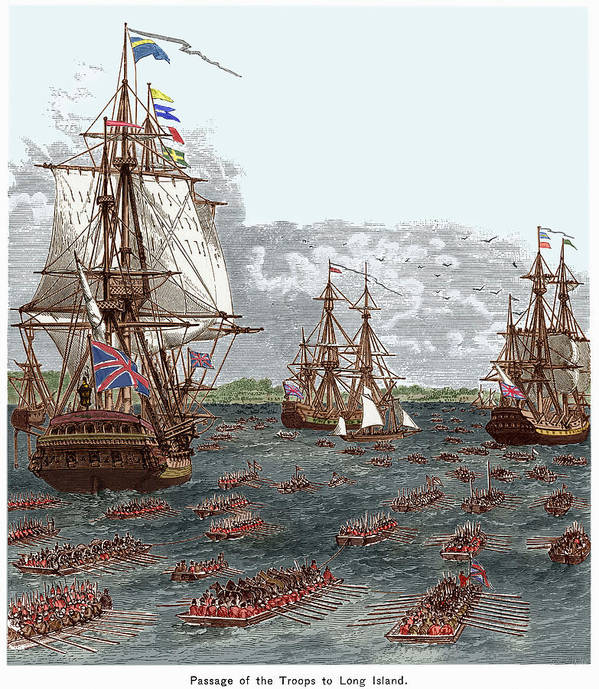

The fleet was not long in coming, the first arrivals dropping anchor by the end of June. Within the week, 130 ships were anchored off Staten Island under the command of Admiral sir Richard Howe, the General’s brother.

The Howe brothers attempted to negotiate on July 14 with a letter to General Washington, addressed: “Georg Washington, Esq.” The letter was returned unopened by Washington’s aide Joseph Reed who explained there’s nobody over here, by that address. Again the letter came back addressed to “George Washington, Esq., etc.,” the etc. meaning… “and any other relevant titles.” That letter too came back unopened but this time, with a message. The general would meet with one of Howe’s subordinates. The meeting took place on July 20 when Howe’s representative offered pardon, for the American side. General Washington responded as they had done nothing wrong his side had no need, of any pardons. But thanks anyway.

By August 12 the British force numbered some 400 vessels with 73 warships and a force of 32,000 camped on Staten island.

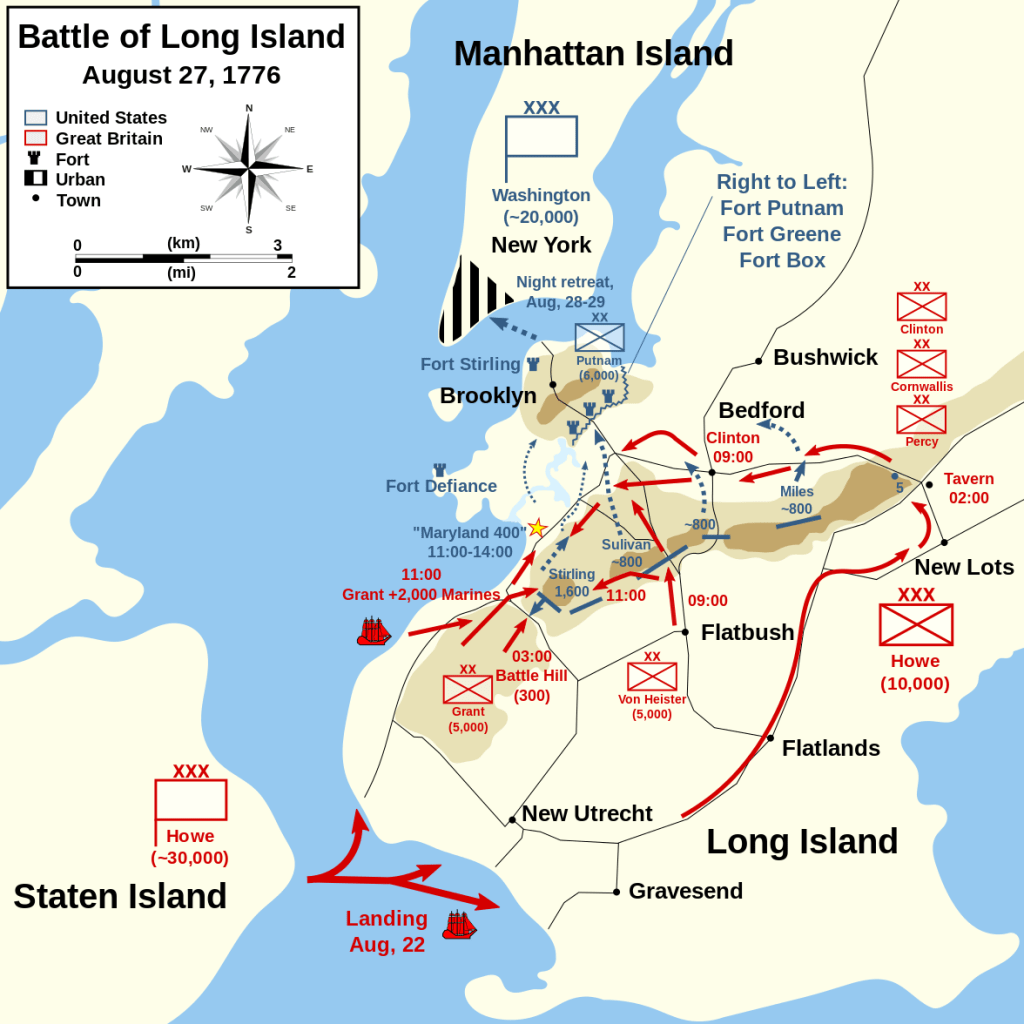

Patriot forces were badly defeated at the Battle of Brooklyn, fought on August 27, 1776. In terms of number of troops deployed and actual combat it was the largest battle, of the Revolution. The British dug in for a siege, confident their adversary was cornered and waiting only to be destroyed at their convenience while the main Patriot army retreated to Brooklyn Heights.

Cornered on land with the British-controlled East River to their backs, it may have been all over for the Patriot cause, but for one of the great tactical feats of all military history. The surprise was complete for the British side, on waking for the morning of August 30 to discover the 9,000-strong Patriot army, had vanished. The silent evacuation over the night of August 29-30 had averted disaster, a feat made possible only through the nautical skills of the merchants and rum traders, the sailors and the fishermen of Colonel John Glover’s Marblehead Massachusetts militia, the “Amphibious Regiment”.

Following evacuation, the Patriot army found itself isolated on Manhattan island, virtually surrounded. Only the thoroughly disagreeable current conditions of the Throg’s Neck-Hell’s Gate segment of the East River, prevented Admiral Sir Richard Howe from enveloping Washington’s position, altogether.

Desperate for information about the attack he was sure would come Washington dispatched a 22-year old Connecticut schoolteacher named Nathan Hale on September 10, to keep an eye on British movements. Disguised as a Dutch schoolteacher, Hale naïvely placed his trust, where it didn’t belong. He was betrayed in just over a week.

As expected, Howe landed a force at Kip’s Bay on September 15 and the Redcoats quickly occupied the city. Patriots delivered an unexpected check the following day at Harlem Heights against an overconfident force of British light troops. It was to be the only such bright spot for the Americans who were now driven out of New York and into New Jersey and finally, to Pennsylvania.

A great fire broke out on the 21st that destroyed as much as a quarter of all the buildings on Manhattan Island. Both sides pointed the finger of blame at the other but the cause, was never determined. Nathan Hale was hanged for a spy the following day with the words, ‘I only regret, that I have but one life to lose for my country‘.

That October, the defeat of General Benedict Arnold’s home-grown “Navy” on the waters near Valcour Island in Vermont, cost the British fleet dearly enough that it had to turn back, buying another year for the Patriot cause.

Reduced to a mere 4,707 fit for duty, Washington faced the decimation of his army by the New Year, with the end of enlistment for fully two-thirds of an already puny force. With nowhere to go but the offense, Washington crossed the Delaware river in the teeth of a straight-up gale over the night of December 25 and defeated a Hessian garrison at Trenton in a surprise attack on the morning of December 26.

While minor skirmishes by British standards, the January 2-3 American victories at Assunpink Creek and Princeton demonstrated an American willingness, to stand up to the most powerful military of the age. Cornwallis suffered three defeats in a ten day period and withdrew his forces from the south of New Jersey. American morale soared as enlistments, came flooding in.

The American war for independence had years to go. Before it was over, more Americans would die in the fetid holds of British prison ships than in every battle of the Revolution, combined. Yet, that first year had come and gone and the former colonies, were still in the fight.

The astonishing part of this story is it all took place in the midst of a plague vastly more deadly than the COVID-19 pandemic, of our own age. Of 2,780,369 counted by the 1770 census* in this country no fewer than 130,000 died in the smallpox pandemic of 1775-1782. That works out to 4,815 per 100,000. Contrast that with a Coronavirus death rate of 194.14 per 100,000 according to Johns Hopkins University a death rate, of less than .2% *This figure does not include Native Americans who were not counted in the US census, until 1860.

A generation later and an ocean away, Lord Arthur Wellesley described the final defeat of a certain Corsican corporal at a place called Waterloo. Wellesley might have been talking about the whole year of 1776 in describing that day in 1815, when he said “It was a damn close run thing”.

Feature image, top of page: Battle of Long Island, by Alonzo Chappel.

A greatly diminished Anglo Saxon army marched south, meeting the Norman invader in October, 1066. History changed that day, when King Harold took an arrow to the eye, at a place called Hastings. The last of the Anglo Saxon Kings, was dead. William was crowned King of England that December. Henceforward and forever more, William the Bastard would be known as “William the Conqueror”.

A greatly diminished Anglo Saxon army marched south, meeting the Norman invader in October, 1066. History changed that day, when King Harold took an arrow to the eye, at a place called Hastings. The last of the Anglo Saxon Kings, was dead. William was crowned King of England that December. Henceforward and forever more, William the Bastard would be known as “William the Conqueror”.

Late in the 12th century, King’s Treasurer Richard FitzNeal likened the Great Survey to the Book of Judgement, the book of “Domesday” (middle English for “Doomsday”), because its pronouncements were final and inviolate as the Last day of Judgement.

Late in the 12th century, King’s Treasurer Richard FitzNeal likened the Great Survey to the Book of Judgement, the book of “Domesday” (middle English for “Doomsday”), because its pronouncements were final and inviolate as the Last day of Judgement.

You must be logged in to post a comment.