The Battle of France began on May 10, 1940 with the German invasion of France and the Low Countries of Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. By the end of May, German Panzer columns had hurled the shattered remnants of the allied armies into the sea, at a place called Dunkirk.

The speed and ferocity of the German Blitzkrieg left the French people shocked and prostrate in the wake of surrender, that June. All those years their government had told them, the strength of the French army combined with the Maginot Line was more than a match for the German military.

The country had fallen in six weeks.

On June 18, Charles DeGaulle addressed the French nation from his exile in Great Britain, exhorting his countrymen to fight on. Resist. The idea caught on quickly in occupied regions.

Germany installed a Nazi-approved French government in the southern part of “La Métropole” that July, headed by WW1 hero Henri Pétain. Resistance against this new government in Vichy was slower to form. This was, after all a French government, and French attitudes took a decidedly anti-English turn with the July 3 British attack on the French fleet, at Mers-el-Kébir.

Before long, Vichy’s collaborationist policies hardened French attitudes against itself. The French Resistance was born.

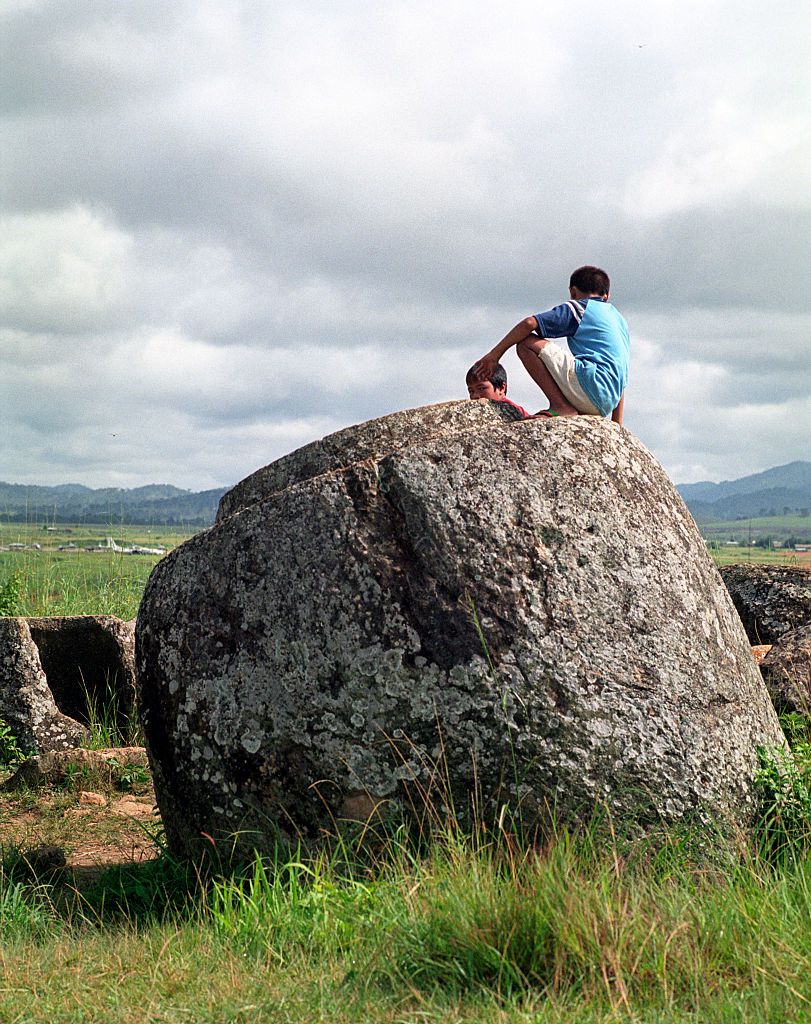

Sometime around this period a tree fell unseen near the French village of Montignac. On September 12, 1940, 18-year old Marcel Ravidat was walking his black & white mongrel dog “Robot”, in the woods. Coming upon the downed tree, the pair noticed a deep hole had opened up, where the tree had once stood. Stories differ as to which of the two went down the hole first, but it soon became clear. Marcel Ravidat and his dog had discovered more than just a hole in the ground.

The boy returned to the site with three buddies: Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel, and Simon Coencas. Entering via a long tunnel, the boys discovered what turned out to be a cave complex, its walls covered with depictions of animals. Hundreds of them.

History has no single narrative. It is a thousand times a thousand, each layered and intertwined with the other. Here, four teenagers in Nazi occupied France had discovered some of the oldest and finest prehistoric art, in the world.

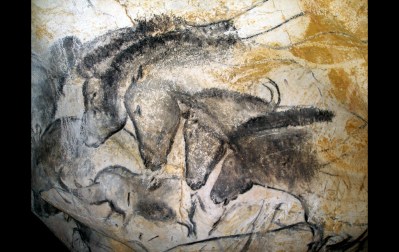

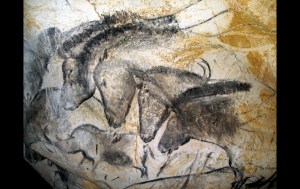

The Lascaux Caves are located in the Dordogne region, in Southwestern France. Some 17,000 years ago, upper Paleolithic artists mixed mineral pigments such as iron oxide (ochre), haematite, and goethite, suspending pigments in animal fat, clay or the calcium-rich groundwater of the caves themselves. Shading and depth were added with charcoal.

The Lascaux Caves are located in the Dordogne region, in Southwestern France. Some 17,000 years ago, upper Paleolithic artists mixed mineral pigments such as iron oxide (ochre), haematite, and goethite, suspending pigments in animal fat, clay or the calcium-rich groundwater of the caves themselves. Shading and depth were added with charcoal.

Colors were swabbed or blotted onto surfaces. There is no evidence of brushwork. Sometimes, pigments were placed in a hollow tube, and blown onto the wall. Where the cave rock is softer, images are engraved.

The color, size, quality and quantity of the images at Lascaux, are astonishing. Abbé Breuil, a Catholic priest and the first expert to examine its walls, called it the “Sistine chapel of prehistory”.

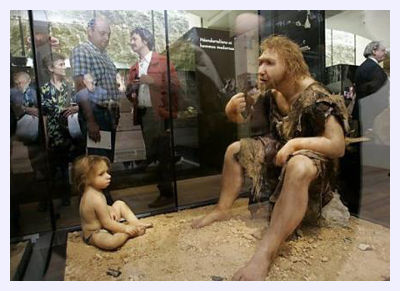

The artist or artists who created such images, nearly 2,000 of them occupying some 37 chambers, would have been recognizable as modern humans. Living as they did some 5,000 years before the Holocene Glacial Retreat, (yes, they had “climate change” back then), these cave-dwellers were pre-agricultural, subsisting on what they could find, or what they could kill.

More than 900 images are recognizable as animals. 605 of them have been precisely identified. Hundreds of pictures depict horses, stag, cattle, lions and bison. Other subjects appear with less frequency. There are seven cats, a bird, a bear, a wooly rhinoceros, and one human.

The purpose served by these images is unclear. Perhaps they tell stories of past hunts, or maybe they were used to call up the spirits for a successful hunt. At least one professor of art and archaeology postulates that the dot and lattice patterns overlying many of these paintings may reflect trance visions, similar to the hallucinations produced by sensory deprivation.

36 animals occupy the “Great Hall of Bulls”, including a single black Auroch specimen measuring some 17-feet, the largest such image ever discovered in cave art. One semi-spherical chamber, the “Apse”, is covered from the floor to its 8-foot 9-inch vaulted ceiling with overlapping, entangled drawings and engravings, demonstrating that these people erected scaffolding to create such work.

The Lascaux caves were used by the French Resistance for weapons storage during the war, and opened to the public in 1948. It would prove to be a mistake.

The underground environment had been stable for all those thousands of years. Now the light, the air circulation, and exhalations of thousands of visitors every day, were irreparably changing the cave environment. By the 1950s, colors had noticeably changed and faded. Crystals and lichens began to grow on the walls, black and white molds grew quickly throughout the cave complex.

The cave was closed to the public in 1963, the paintings restored and a monitoring system installed. To this day molds, lichens and crystallized minerals bedevil the art of the Lascaux caves. Only a handful of scientific experts are now permitted access to the site, and that’s only for a few days per month. Some of the most eminent preservation specialists on the planet continue to wrestle with the problem.

The prehistory buff can find a lot to like in the Vézère region of France. The valley has 147 prehistoric sites, 15 of them listed as Unesco World Heritage sites.

“Lascaux II” opened in 1983, an exact replica of the Hall of the Bulls and the “Painted Gallery” areas at the original, educating and informing the public without further harm to the original.

An 800 square meter mobile “Lascaux 3” began a world tour in 2012, a series of five reproductions bringing a taste of the original, to visitors from around the world. Most recently, the €57 million ($68 million), multi-media Lascaux IV opened last December, 8,500 square meters of high-tech exhibit space where each visitor is free to explore four exhibition rooms, equipped with an electronic compagnon de visite, a tablet-like device which looks like it’s been flaked and formed out of slate, Fred Flintstone style.

If you would permit me personal note, years ago, the Long family convened our annual “Blue Gray Ramble” at the Petersburg battlefield, in Virginia. There’s a cut running parallel to the battle lines there, not far from the crater. The ravine is 12 feet deep in places, narrowing downward to a hard, dry stream bed.

Working our way down the bottom of the cut, my son Dan discovered an archaeologist’s dream of fossils: Gastropods, scallop shells, copepods and shark’s teeth. The denizens of a long forgotten sea, cast in stone and exposed on the light of a Civil War battlefield.

We were there that weekend to discover history. What we found brought a new and unexpected perspective.

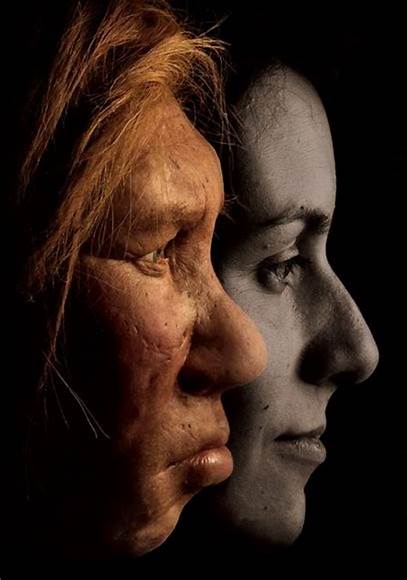

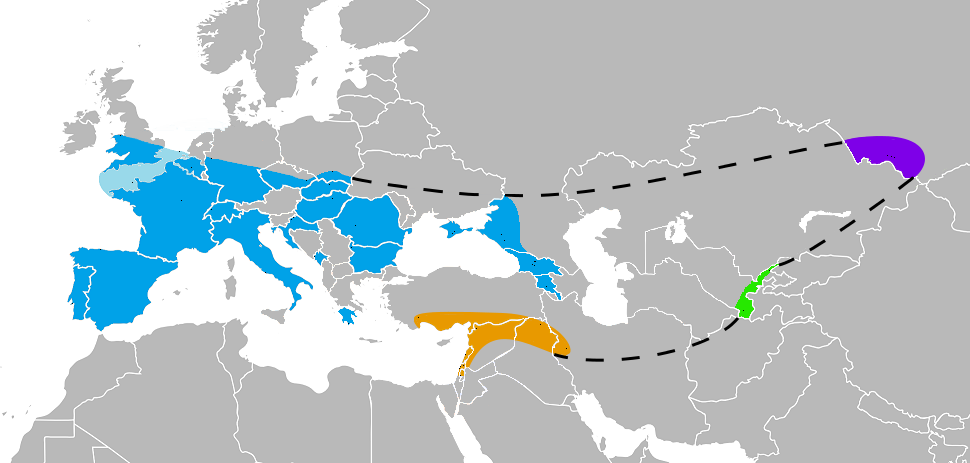

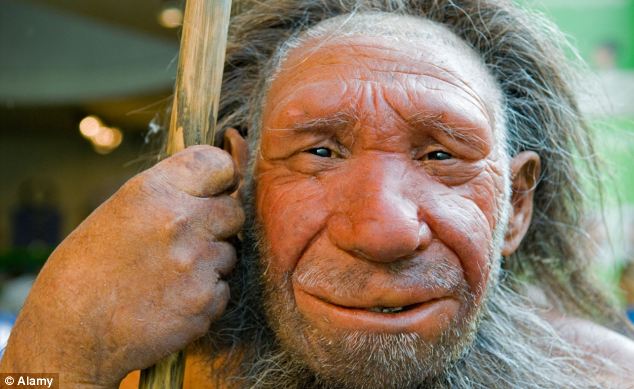

Research suggests that we ourselves carry Neanderthal genes, those among us of Eurasian ancestry. These genes may have changed our immune systems leaving us vulnerable to diseases such diabetes and cancer.

Research suggests that we ourselves carry Neanderthal genes, those among us of Eurasian ancestry. These genes may have changed our immune systems leaving us vulnerable to diseases such diabetes and cancer.

The hyoid bone at the floor of the mouth serves as a connecting-point for the tongue and other musculature, giving humans the ability to speak. A delicate structure likely to be lost in most fossilized specimens, the first Neanderthal hyoid was only discovered in 1989.

The hyoid bone at the floor of the mouth serves as a connecting-point for the tongue and other musculature, giving humans the ability to speak. A delicate structure likely to be lost in most fossilized specimens, the first Neanderthal hyoid was only discovered in 1989.

The idea isn’t as strange as it sounds. Last year, Sir Richard Branson was in the news, claiming he’d looked into his family ancestry. Forty generations back, turns out Branson is related to Charlemagne. It’s no big deal, according to Geneticist Adam Rutherford. Speaking at the Chalke Valley History Festival, Rutherford explained: “Literally every person in Europe is directly descended from Charlemagne. Literally, not metaphorically. You have a direct lineage which leads to Charlemagne,” adding “Looking around this room, every single one of you … is directly descended between 21 and 24 generations from Edward III.”

The idea isn’t as strange as it sounds. Last year, Sir Richard Branson was in the news, claiming he’d looked into his family ancestry. Forty generations back, turns out Branson is related to Charlemagne. It’s no big deal, according to Geneticist Adam Rutherford. Speaking at the Chalke Valley History Festival, Rutherford explained: “Literally every person in Europe is directly descended from Charlemagne. Literally, not metaphorically. You have a direct lineage which leads to Charlemagne,” adding “Looking around this room, every single one of you … is directly descended between 21 and 24 generations from Edward III.” If you have European or Asian ancestry, the following traits might be a sign of your inner Neanderthal:

If you have European or Asian ancestry, the following traits might be a sign of your inner Neanderthal: The naturally large eyes of individuals such as Ukrainian model Masha Tyelna are believed to have been useful to Neanderthal, making their way in the dim light of northern latitudes. In fact, Neanderthal may have used more brain power processing visual input: an evolutionary disadvantage compared with early modern humans.

The naturally large eyes of individuals such as Ukrainian model Masha Tyelna are believed to have been useful to Neanderthal, making their way in the dim light of northern latitudes. In fact, Neanderthal may have used more brain power processing visual input: an evolutionary disadvantage compared with early modern humans.

Freckles? Fair skin is more efficient at producing vitamin D from weak sunlight, an advantage for those living at northern latitudes. Freckles result from clusters of cells which overproduce melanin granules, triggered by exposure to sunlight. Freckles are found in a wide range of skin colors and ethnicity, but are most prevalent on fair complexions. It is a Neanderthal gene most common in Eurasians, among whom 70% are believed to carry the gene.

Freckles? Fair skin is more efficient at producing vitamin D from weak sunlight, an advantage for those living at northern latitudes. Freckles result from clusters of cells which overproduce melanin granules, triggered by exposure to sunlight. Freckles are found in a wide range of skin colors and ethnicity, but are most prevalent on fair complexions. It is a Neanderthal gene most common in Eurasians, among whom 70% are believed to carry the gene.

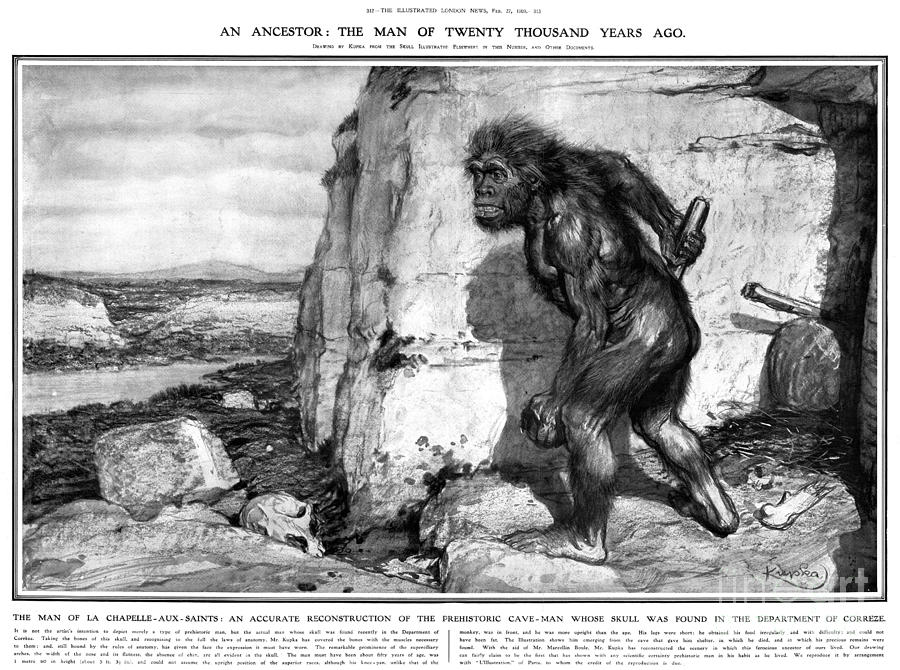

Shorter in stature and considerably more powerful than Cro-Magnon, our direct ancestor and all but indistinguishable from ourselves, Neanderthal bodies were suited to the ice age of the early and middle Paleolithic era.

Shorter in stature and considerably more powerful than Cro-Magnon, our direct ancestor and all but indistinguishable from ourselves, Neanderthal bodies were suited to the ice age of the early and middle Paleolithic era.

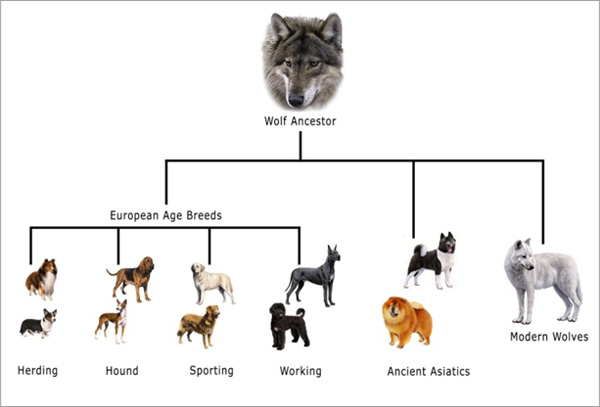

It may be hard to imagine but, Canis lupus, the wolf, is the ancestor of the modern dog, Canis familiaris. Every one of them, from Newfoundlands to Chihuahuas.

It may be hard to imagine but, Canis lupus, the wolf, is the ancestor of the modern dog, Canis familiaris. Every one of them, from Newfoundlands to Chihuahuas.

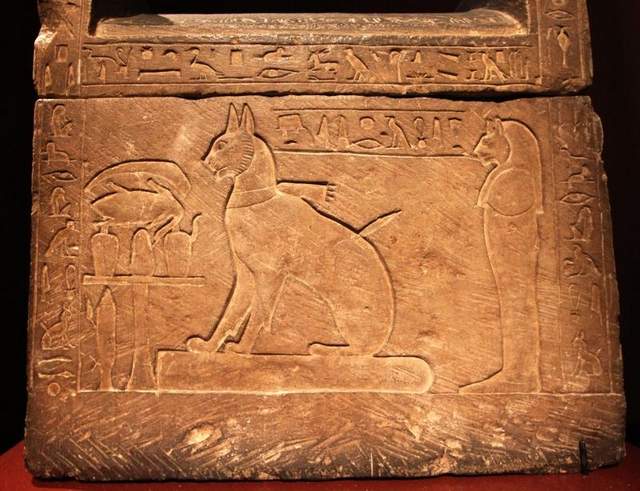

Sus scrofa (the pig) was domesticated around 6000 BC throughout the Middle East and China. Pigs were originally used as draft animals. There are stone engravings depicting teams of hogs hauling war chariots. I wonder what that sounded like.

Sus scrofa (the pig) was domesticated around 6000 BC throughout the Middle East and China. Pigs were originally used as draft animals. There are stone engravings depicting teams of hogs hauling war chariots. I wonder what that sounded like.

Early camelids spread across the Bering land bridge, moving the opposite direction from the Asian immigration to America, surviving in the Old World and eventually becoming domesticated and spreading globally by humans. The first “camelids” became domesticated about 4,500 years ago in Peru: The “New World Camels” the Llama and the Alpaca, and the “South American Camels”, the Guanaco and the Vicuña.

Early camelids spread across the Bering land bridge, moving the opposite direction from the Asian immigration to America, surviving in the Old World and eventually becoming domesticated and spreading globally by humans. The first “camelids” became domesticated about 4,500 years ago in Peru: The “New World Camels” the Llama and the Alpaca, and the “South American Camels”, the Guanaco and the Vicuña.

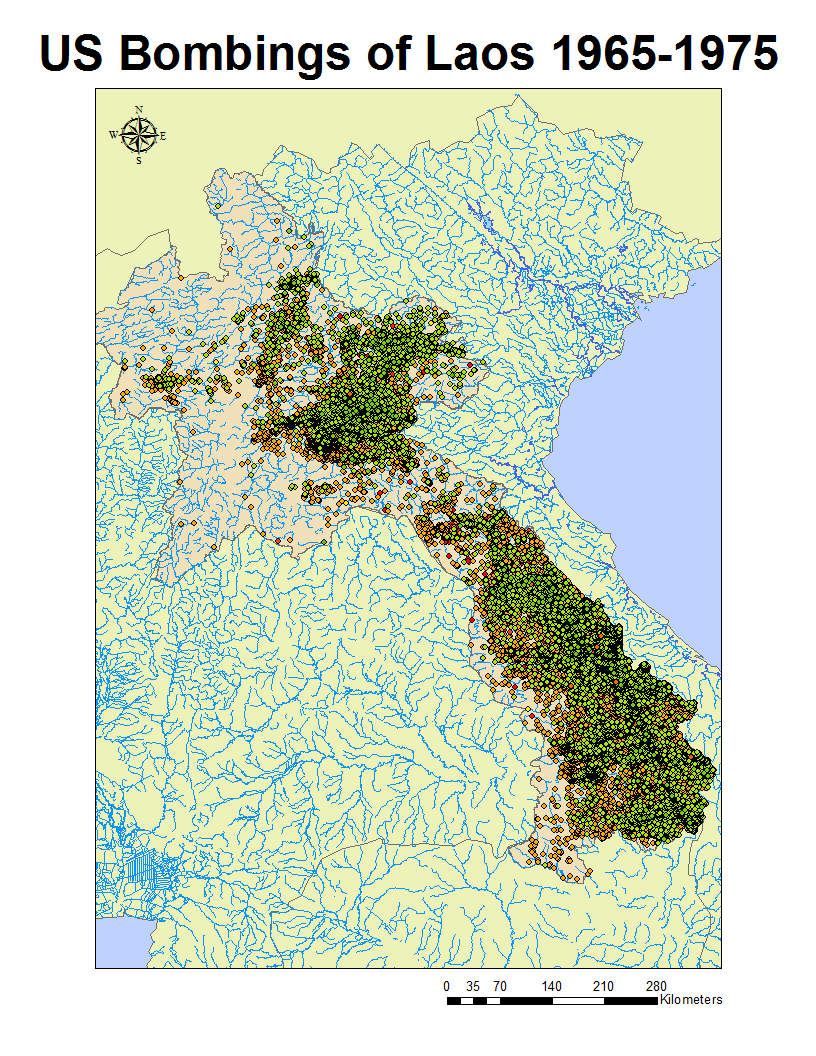

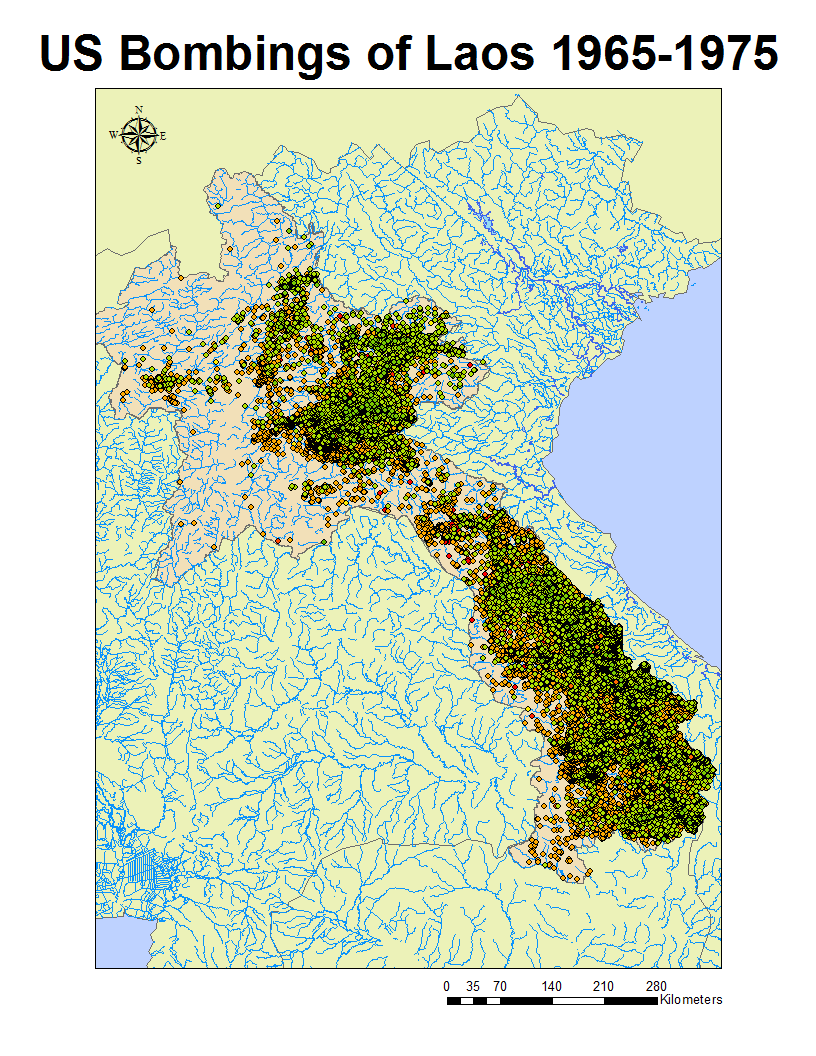

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

The Geneva Convention of 1954 partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, and guaranteed Laotian neutrality. North Vietnamese communists had no intention of withdrawing from the country or abandoning their Laotian communist allies, any more than they were going to abandon the drive for military reunification, with the south.

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

On February 18, 1977, Murray Hiebert, now senior associate of the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. summed up the situation in a letter to the Mennonite Central Committee, US: “…a formerly prosperous people still stunned and demoralized by the destruction of their villages, the annihilation of their livestock, the cratering of their fields, and the realization that every stroke of their hoes is potentially fatal.”

The Lascaux Caves are located in the Dordogne region, in Southwestern France. Some 17,000 years ago, Upper Paleolithic artists mixed mineral pigments such as iron oxide (ochre), haematite, and goethite, suspending pigments in animal fat, clay or the calcium-rich groundwater of the caves themselves. Shading and depth were added with charcoal.

The Lascaux Caves are located in the Dordogne region, in Southwestern France. Some 17,000 years ago, Upper Paleolithic artists mixed mineral pigments such as iron oxide (ochre), haematite, and goethite, suspending pigments in animal fat, clay or the calcium-rich groundwater of the caves themselves. Shading and depth were added with charcoal. The artist or artists who created such images, nearly 2,000 of them occupying some 37 chambers, would have been recognizable as modern humans. Living as they did some 5,000 years before the Holocene Glacial Retreat, (yes, they had “climate change” back then), these cave-dwellers were pre-agricultural, subsisting on what they could find, or what they could kill.

The artist or artists who created such images, nearly 2,000 of them occupying some 37 chambers, would have been recognizable as modern humans. Living as they did some 5,000 years before the Holocene Glacial Retreat, (yes, they had “climate change” back then), these cave-dwellers were pre-agricultural, subsisting on what they could find, or what they could kill. The purpose served by these images is unclear. Perhaps they tell stories of past hunts, or maybe they were used to call up the spirits for a successful hunt. At least one professor of art and archaeology postulates that the dot and lattice patterns overlying many of these paintings may reflect trance visions, similar to the hallucinations produced by sensory deprivation.

The purpose served by these images is unclear. Perhaps they tell stories of past hunts, or maybe they were used to call up the spirits for a successful hunt. At least one professor of art and archaeology postulates that the dot and lattice patterns overlying many of these paintings may reflect trance visions, similar to the hallucinations produced by sensory deprivation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.