In AD732, a Frankish military force led by Charles Martel, the illegitimate son of Pippin II of Herstal, met a vastly superior invading army of the Umayyad Caliphate, led by Abd Ar-Rahman al Ghafiqi.

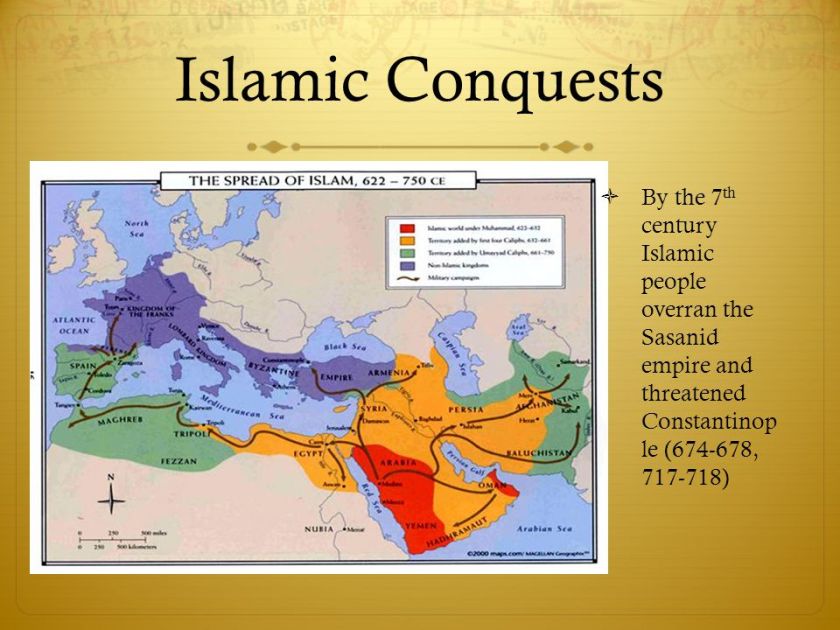

The Umayyad Caliphate had recently defeated two of the most powerful militaries of the era. The Sassanid empire in modern day Iran had been destroyed altogether, as was the greater part of the Byzantine Empire, including Armenia, North Africa and Syria.

As the Caliphate grew in strength, European civilization faced a period of reduced trade, declining population and political disintegration, characterized by a constellation of new and small kingdoms, evolving and squabbling for suzerainty over the common people.

The “Banu Umayya”, the second of four major dynasties established following the death of Muhammad 100 years earlier, was already one of the largest, most powerful empires in history. Should it fail, no force stood behind the Frankish host, sufficient to prevent a united Islamic caliphate stretching from the Atlantic coast of Spain to the Indian sub-continent, from Sub-Saharan Africa to the North Sea.

With no cavalry of his own, Charles faced a two-to-one disadvantage in the face of a combined Islamic force of infantry and horse soldiers. History offers few instances of medieval armies withstanding the charge of cavalry, yet Charles had anticipated this moment. He had trained his men, they were ready.

The story is familiar. Charles “The Hammer” Martel met the invader, at a spot between the villages of Tours, and Poitiers. Despite all odds, the Frankish force emerged victorious, from the Battle of Tours (Poitiers). Western civilization, was saved.

Forgotten in this narrative, is the story of the man who made it all possible.

Twenty years earlier, a combined force of 1,700 Arab and North African horsemen, the Berbers, landed on the Iberian Peninsula led by Tariq Ibn Ziyad. Within ten years, the Emir of Córdoba ruled over most of what we now call Portugal and Spain, save for the fringes of the Pyrenean mountains, and the highlands along the northwest coastline.

In AD721, Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani, wali (governor) of Muslim Spain, built a strong army from the Umayyad territories of Al-Andalus, and invaded the semi-independent duchy of Aquitaine, a principality ostensibly part of the Frankish kingdom, but for all intents and purposes ruled as an independent territory.

Duke Odo of Aquitaine left his home in Toulouse in search of help, from the Frankish statesman and military leader, Charles Martel. This was a time (718 – 732) of warring kingdoms and duchys, a consolidation of power in which Martel preferred not to step up on behalf of his southern rival, but to wait, and see what happened. Odo, Duke of Aquitaine, was on his own.

At this time, Toulouse was the largest and most important city in Aquitaine. Believing Odo to have fled before their advance, the forces of al-Andalus laid siege to the city, secure in the belief that their only threat lay before them. For three months, Odo gathered Aquitanian, Gascon and Frankish troops about him, as his city held on.

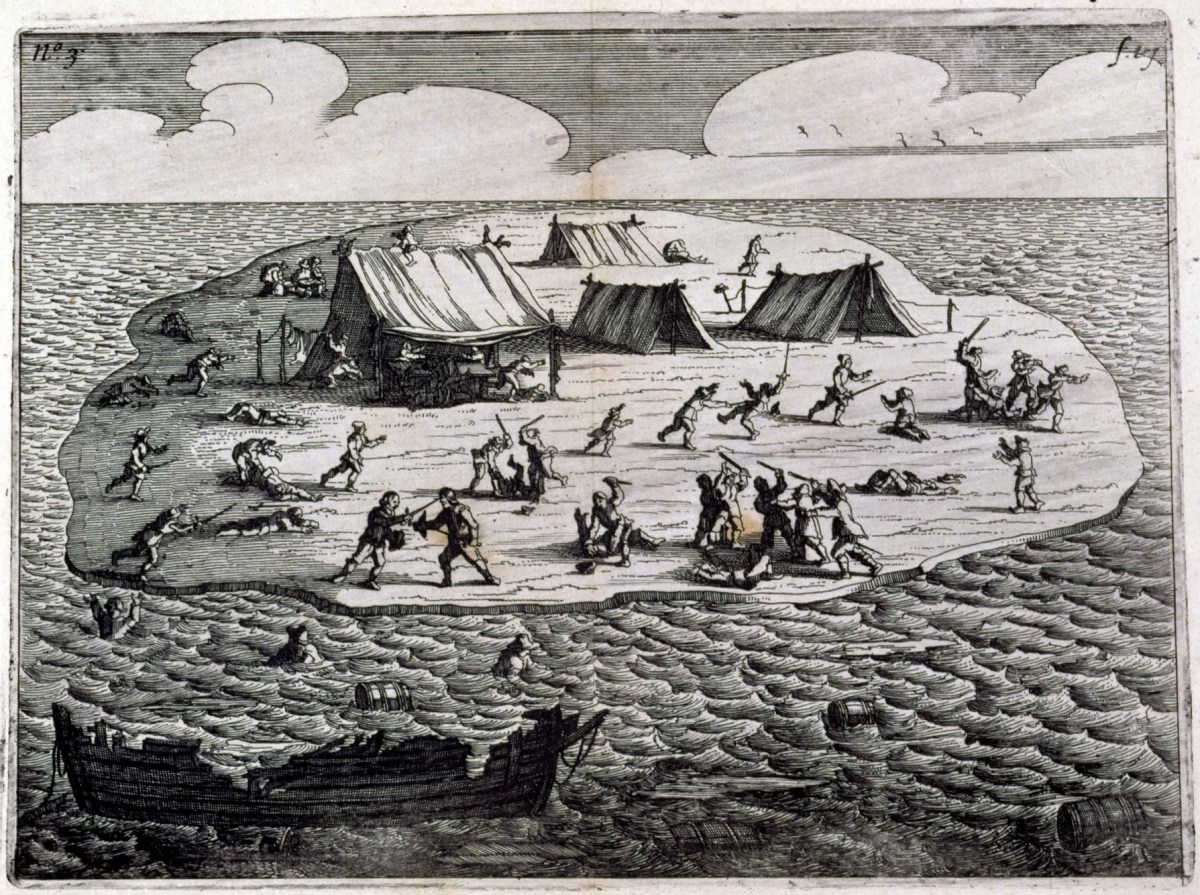

Overconfident, the besieging army had failed to fortify its outer perimeter, or to scout the surrounding countryside. On June 9 with Toulouse on the verge of collapse, the armies of Duke Odo fell on the Muslim rear, as defenders poured from the city gates, an avenging army. Sources report Duke Odo’s forces numbered some 300,000, though the number is almost certainly exaggerated.

Caught at rest without weapons or amour, the surprise was complete. Some 350,000 Umayyad troops are said to have been cut down as they fled, but again, the number is probably inflated. Al-Samh himself was mortally wounded, and later died in Narbonne.

Be that as it may, the battle of Toulouse was an unmitigated disaster for the Arab side. Some historians believe that this day in 721 did more to check the Muslim advance into western Europe, than did the later battle at Tours. For 450 years, Muslim chroniclers at Al-Andalus described the battle as Balat al Shuhada (‘the path of the martyrs’), while Tours was remembered as a relatively minor skirmish.

One of those to escape with his life, was a young Abd Ar-Rahman al Ghafiqi. Eleven years later in 732, the now – governor of Al-Andalus would once again cross the Pyrenees, this time at the head of a massive army of his own. Al Ghafiqi’s legions laid waste to Navarre and Gascony, first destroying Auch, and then Bordeaux. Duke Odo “The Great” would be destroyed at the River Garonne and the table set for the all-important decision of Tours.

One of those to escape with his life, was a young Abd Ar-Rahman al Ghafiqi. Eleven years later in 732, the now – governor of Al-Andalus would once again cross the Pyrenees, this time at the head of a massive army of his own. Al Ghafiqi’s legions laid waste to Navarre and Gascony, first destroying Auch, and then Bordeaux. Duke Odo “The Great” would be destroyed at the River Garonne and the table set for the all-important decision of Tours.

In history as in life, time and place is everything. Today, Duke Odo of Aquitaine is all but forgotten. We remember Charles “The Hammer” Martel as the savior of western civilization, as well we should. Yet, we need not forget the man who made it possible, who gave Martel time to gather the strength, to forge the fighting force which gave life to such an unlikely outcome.

In the late 19th century, Europe was embarked on yet another of its depressingly regular paroxysms of anti-Semitism, when a French Captain of Jewish Alsatian extraction by the name of Alfred Dreyfus was arrested, for selling state secrets to Imperial Germany.

In the late 19th century, Europe was embarked on yet another of its depressingly regular paroxysms of anti-Semitism, when a French Captain of Jewish Alsatian extraction by the name of Alfred Dreyfus was arrested, for selling state secrets to Imperial Germany. Chief Inspector Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Armand Auguste Ferdinand Mercier du Paty de Clam, himself no handwriting expert, agreed with Bertillon. With no file to go on and despite the feebleness of the evidence, de Clam summoned Dreyfus for interrogation on October 13, 1894.

Chief Inspector Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Armand Auguste Ferdinand Mercier du Paty de Clam, himself no handwriting expert, agreed with Bertillon. With no file to go on and despite the feebleness of the evidence, de Clam summoned Dreyfus for interrogation on October 13, 1894.

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus. The public outcry became furious in January 1898 when author Émile Zola published a bitter denunciation in an open letter to the Paris press, entitled “J’accuse” (I Blame).

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus. The public outcry became furious in January 1898 when author Émile Zola published a bitter denunciation in an open letter to the Paris press, entitled “J’accuse” (I Blame).

Perhaps the man was ill at the time but, be that as it may, the die was cast. The conspirators now needed only the right set of circumstances, to put their plans in motion.

Perhaps the man was ill at the time but, be that as it may, the die was cast. The conspirators now needed only the right set of circumstances, to put their plans in motion.

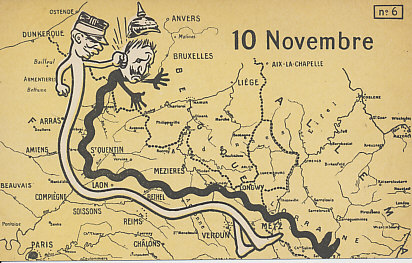

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers. German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”.

German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”. Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

Even so, there is evidence of a small Christmas truce occurring in 1916, previously unknown to historians. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

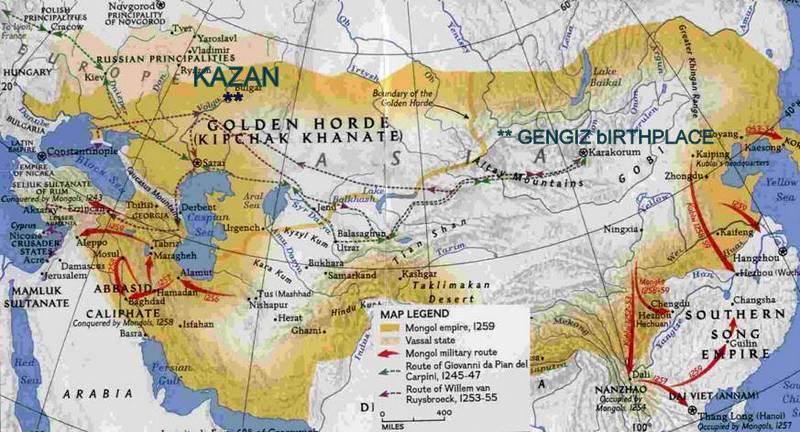

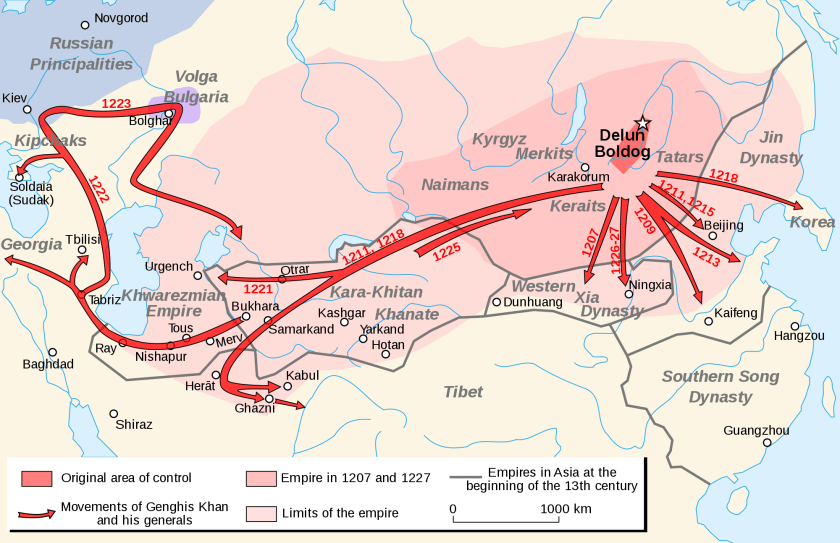

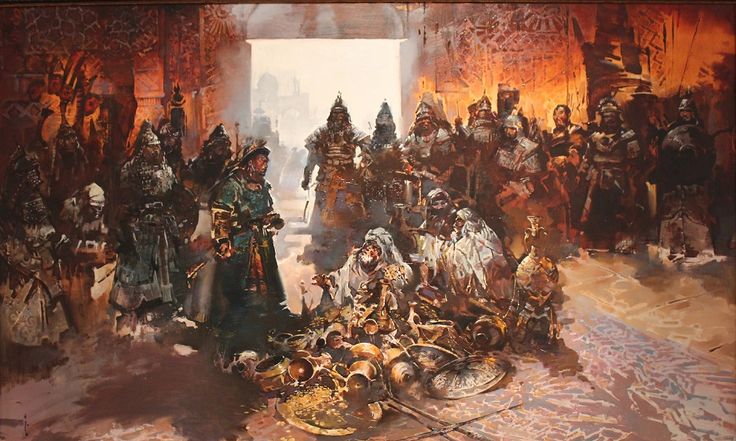

The Steppes have long been a genetic crossroad, the physical features of its inhabitants as diverse as any in the world. The word “Rus”, from which we get Russia, was the name given to Viking invaders from earlier centuries. History does not record what Genghis himself looked like, though he’s often depicted with Asian features. There is evidence suggesting he had red hair and green eyes. Think of that beautiful young Afghan girl, the one with those killer eyes on that National Geographic cover, a few years back.

The Steppes have long been a genetic crossroad, the physical features of its inhabitants as diverse as any in the world. The word “Rus”, from which we get Russia, was the name given to Viking invaders from earlier centuries. History does not record what Genghis himself looked like, though he’s often depicted with Asian features. There is evidence suggesting he had red hair and green eyes. Think of that beautiful young Afghan girl, the one with those killer eyes on that National Geographic cover, a few years back.

The Mongols would never regain the lost high ground of December 1241, as chieftains fell to squabbling over bloodlines.

The Mongols would never regain the lost high ground of December 1241, as chieftains fell to squabbling over bloodlines.

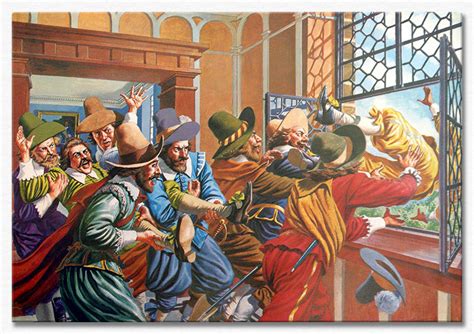

English Catholics became increasingly marginalized for the remainder of Henry’s reign, and that of his daughter, Elizabeth I, who died in 1603 without issue. There were several assassination attempts against Protestant rulers in Europe and England, including a failed plot to poison Elizabeth I, and the assassination of French King Henry III, who was stabbed to death by a Catholic fanatic in 1589.

English Catholics became increasingly marginalized for the remainder of Henry’s reign, and that of his daughter, Elizabeth I, who died in 1603 without issue. There were several assassination attempts against Protestant rulers in Europe and England, including a failed plot to poison Elizabeth I, and the assassination of French King Henry III, who was stabbed to death by a Catholic fanatic in 1589. Guy Fawkes, who had 10 years of military experience fighting for the King of Spain in the Netherlands, was put in charge of the explosives.

Guy Fawkes, who had 10 years of military experience fighting for the King of Spain in the Netherlands, was put in charge of the explosives. So it is that today, November 5th, is “Guy Fawkes Day”. People all over England will “remember, remember, the 5th of November, gunpowder, treason and plot.” Effigies of Guy Fawkes will be burned throughout the land.

So it is that today, November 5th, is “Guy Fawkes Day”. People all over England will “remember, remember, the 5th of November, gunpowder, treason and plot.” Effigies of Guy Fawkes will be burned throughout the land.

This invasion force, commanded by General Arthur Aitkin, spent that first day and most of the second sweeping for non-existent mines, before finally assembling an assault force on the beaches late on November 3rd. It was a welcome break for the German Commander, Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, who had assembled and trained a force of Askari warriors around a core of white German commissioned and non-commissioned officers.

This invasion force, commanded by General Arthur Aitkin, spent that first day and most of the second sweeping for non-existent mines, before finally assembling an assault force on the beaches late on November 3rd. It was a welcome break for the German Commander, Colonel Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck, who had assembled and trained a force of Askari warriors around a core of white German commissioned and non-commissioned officers.

Colonel, and later General Lettow-Vorbeck, was called “

Colonel, and later General Lettow-Vorbeck, was called “ Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck came to loathe Adolf Hitler, and tried to establish a conservative opposition to the Nazi political machine. When offered the ambassadorship to the Court of St. James in 1935, he apparently did more than merely decline the job. He told Der Fuehrer to perform an anatomically improbable act. Years later, Charles Miller asked the nephew of a Schutztruppe officer about the exchange. “I understand that von Lettow told Hitler to go f**k himself”. “That’s right”Came the reply, “except that I don’t think he put it that politely”.

Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck came to loathe Adolf Hitler, and tried to establish a conservative opposition to the Nazi political machine. When offered the ambassadorship to the Court of St. James in 1935, he apparently did more than merely decline the job. He told Der Fuehrer to perform an anatomically improbable act. Years later, Charles Miller asked the nephew of a Schutztruppe officer about the exchange. “I understand that von Lettow told Hitler to go f**k himself”. “That’s right”Came the reply, “except that I don’t think he put it that politely”.

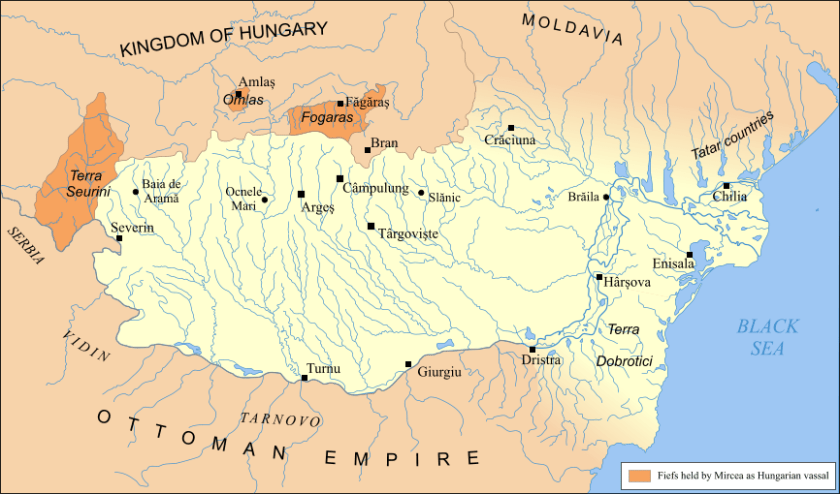

In 1436, Vlad II became voivode, (prince), of Wallachia. The sobriquet “Dracul” came from membership in the “Order of the Dragon” (literally “Society of the Dragonists”), a monarchical chivalric order founded by

In 1436, Vlad II became voivode, (prince), of Wallachia. The sobriquet “Dracul” came from membership in the “Order of the Dragon” (literally “Society of the Dragonists”), a monarchical chivalric order founded by

Ethnic Germans had long since emigrated to these parts, forming a distinct merchant class in Wallachian society. These Saxon merchants were allied with the boyars. It was not long before they too, found themselves impaled on spikes.

Ethnic Germans had long since emigrated to these parts, forming a distinct merchant class in Wallachian society. These Saxon merchants were allied with the boyars. It was not long before they too, found themselves impaled on spikes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.