In September 1935, the Imperial Japanese Navy was conducting wargame maneuvers, when the fourth fleet was caught in extremely foul weather. By the 26th, the storm had reached Typhoon status, The damage to the Japanese fleet was near catastrophic. Two large destroyers had their bows torn away by heavy seas. Several heavy cruisers suffered major structural damage. Submarine tenders and light aircraft carriers developed serious cracks in their hulls. One minelayer required near total rebuild, and virtually all fleet destroyers suffered damage to their superstructures. 54 crewmen were lost.

Nine years later, it would be the turn of the American fleet.

The war in the Pacific was in its third year in December 1944. A comprehensive defeat only weeks earlier had dealt the Imperial Japanese war effort a mortal blow at Leyte Gulf, yet the war would go on for the better part of another year.

Carrier Task Force 38 was a massive assembly of warships, a major element of the 3rd Fleet under the Command of Admiral William “Bull” Halsey. In formation, TF-38 moved in three eight-mile diameter circles, each with an outer ring of destroyers, an inner ring of battleships and cruisers, and a mixed core of 35,000-ton Essex class and smaller escort carriers. TF-38 was a massive force, fielding eighty-six warships, altogether.

By mid-December 1944, Task Force 38 had been underway for three weeks, having just completed three days of heavy raids against Japanese airfields in the Philippines, suppressing enemy aircraft in support of American amphibious operations against Mindoro. Ships were badly in need of re-supply. A replenishment fleet, 35 ships in all, was sent to the nearest spot near Luzon, yet still outside of Japanese fighter range. Replenishment operations began the morning of the 17th.

Rapid movement into previously enemy-held territory made it impossible to establish advance weather reporting. By the time that Task Force aerological (meteorological) service reports made it to ships in the operating area, weather reports were at least twelve hours old.

Three days earlier, a barometric low pressure system had begun to form off Luzon, fed by the warm waters of the Philippine sea. High tropospheric humidity fed and strengthened the disturbance, as counter-clockwise winds began to develop around the low pressure center. By the 18th, this small “tropical disturbance” had developed into a compact but powerful cyclone.

Replenishment operations began the morning of the 17th, as increasing winds and building seas made refueling increasingly difficult. Refueling hoses were parted on several occasions and thick hawsers had to be cut to avoid collision, as sustained winds built to 40 knots. Believing the storm center to be 450 miles to his southeast, Admiral Halsey didn’t want to return to base. That would take too long, and combat operations were scheduled to resume, two days later. Halsey needed the carrier group refueled and on station, and so it was decided. Task Force 38 and the replenishment fleet, would proceed to a second replenishment point, hoping to resume refueling operations on the morning of the 18th.

Four times over the night of December 17-18, course was corrected in the search for calmer water. Four times, the ships of Task Force 38 and it’s attendant resupply ships, turned closer to the eye of the storm. 2,200-ton destroyers pitched and rolled like corks, towering over the crest of 70-waves, only to crash into the trough of the next, shuddering like cold dogs as decks struggled to shed thousands of tons of water.

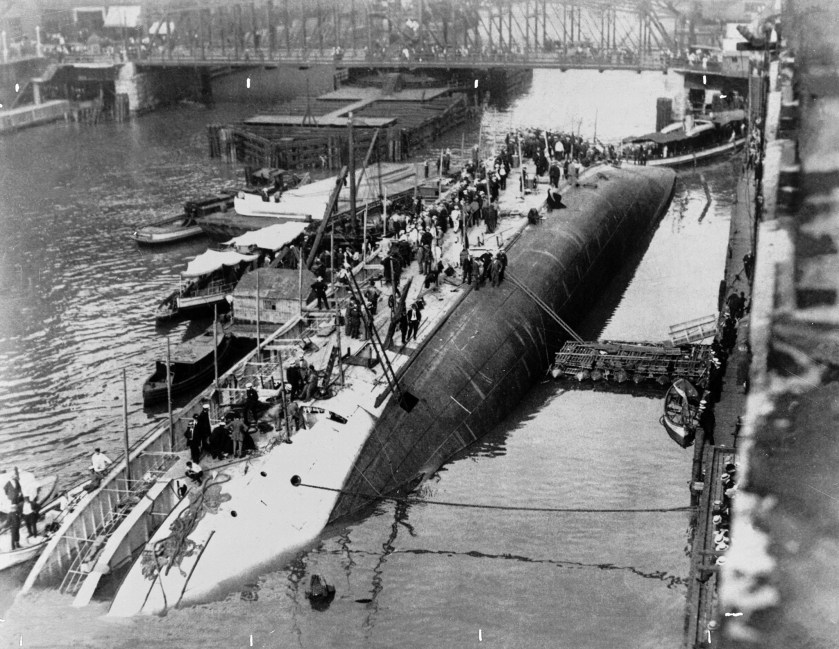

Hulls would creak and groan with the pounding and rivets popped. Captains in wheelhouses would order course headings, but helmsmen could do no better than 50° to either side of the intended course. Some ships rolled more than 70°. The 888-ft carrier USS Hancock, scooped tons of water onto its flight decks, 57′ up.

Typhoon Cobra reached peak ferocity between 1100 and 1400, with sustained winds of 100mph and gusts of up to 140.

The lighter destroyers got the worst of it, finding themselves “in irons” – broad side to the wind and rolling as much as 75°, with no way to regain steering control. Some managed to pump seawater into fuel tanks to increase stability, while others rolled and couldn’t recover, as water cascaded down smokestacks and disabled engines.

146 aircraft were either wrecked or blown overboard. The carrier USS Monterrey nearly went down in flames, as loose airplanes crashed about on hanger decks and burst into flames. One of those fighting fires aboard Monterrey was then-Lieutenant Gerald Ford, the former Michigan Wolverine center and future President of the United States.

Many of the ships of TF-38 sustained damage to above-decks superstructure, knocking out radar equipment and crippling communications.

790 Americans lost their lives in Typhoon Cobra, killed outright or washed overboard and drowned.

It could have been worse. The destroyer escort USS Tabberer defied orders to return to port, Lieutenant Commander Henry Lee Plage conducting a 51-hour boxed search for survivors, despite the egregious pounding being taken by his own ship. USS Tabberer plucked 55 swimmers from the water, survivors of the capsized destroyers Hull and Spence.

Typhoon Cobra moved on that night, December 19 dawning clear with brisk winds. Admiral Halsey ordered “All ships of the Task Force line up side-by-side at about ½ mile spacing and comb the 2800-square mile area” in which they’d been operating. Carl M. Berntsen, SoM1/C aboard the destroyer USS DeHaven, recalled that “I saw the line of ships disappear over the horizon to starboard and to port”. The Destroyer USS Brown rescued six survivors from the Monaghan, and another 13 from USS Hull. 18 more would be plucked from the water, 93 in all, by ships spread across 50-60 miles of open ocean.

When it was over, Admiral Chester Nimitz said typhoon Cobra “represented a more crippling blow to the Third Fleet than it might be expected to suffer in anything less than a major action.”

Afterward

Carl Martin Berntsen passed away on October 13th, 2014 in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. He would have been 94, the following month. I am indebted to him and his excellent essay for this story. Virtually all ships of Task Force 38 were damaged to some degree. I tip my hat to Wikipedia, for the following summary of the more serious instances.

USS Hull – with 70% fuel aboard, capsized and sunk with 202 men drowned (62 survivors)

USS Monaghan – capsized and sunk with 256 men drowned (six survivors)

USS Spence – rudder jammed hard to starboard, capsized and sunk with 317 men drowned (23 survivors) after hoses parted attempting to refuel from New Jersey because they had also disobeyed orders to ballast down directly from Admiral Halsey

USS Cowpens – hangar door torn open and RADAR, 20mm gun sponson, whaleboat, jeeps, tractors, kerry crane, and 8 aircraft lost overboard. One sailor lost.

USS Monterey – hangar deck fire killed three men and caused evacuation of boiler rooms requiring repairs at Bremerton Navy yard

USS Langley – damaged

USS Cabot – damaged

USS San Jacinto – hangar deck planes broke loose and destroyed air intakes, vent ducts and sprinkling system causing widespread flooding. Damage repaired by USS Hector

USS Altamaha – hangar deck crane and aircraft broke loose and broke fire mains

USS Anzio – required major repair

USS Nehenta – damaged

USS Cape Esperance – flight deck fire required major repair

USS Kwajalein – lost steering control

USS Iowa – propeller shaft bent and lost a seaplane

USS Baltimore – required major repair

USS Miami – required major repair

USS Dewey – lost steering control, RADAR, the forward stack, and all power when salt water shorted main electrical switchboard

USS Aylwin – required major repair

USS Buchanan – required major repair

USS Dyson – required major repair

USS Hickox – required major repair

USS Maddox – damaged

USS Benham – required major repair

USS Donaldson – required major repair

USS Melvin R. Nawman – required major repair

USS Tabberer – lost foremast

USS Waterman – damaged

USS Nantahala – damaged

USS Jicarilla – damaged

USS Shasta – damaged “one deck collapsed, aircraft engines damaged, depth charges broke loose, damaged “

There was strong sentiment at the time, that German sabotage lay behind the disaster. A front-page headline on the December 10 Halifax Herald Newspaper proclaimed “Practically All the Germans in Halifax Are to Be Arrested”.

There was strong sentiment at the time, that German sabotage lay behind the disaster. A front-page headline on the December 10 Halifax Herald Newspaper proclaimed “Practically All the Germans in Halifax Are to Be Arrested”.

This is no Charlie Brown shrub we’re talking about. The 1998 tree required 3,200 man-hours to decorate: 17,000 lights connected by 4½ miles of wire, and decorated with 8,000 bulbs.

This is no Charlie Brown shrub we’re talking about. The 1998 tree required 3,200 man-hours to decorate: 17,000 lights connected by 4½ miles of wire, and decorated with 8,000 bulbs.

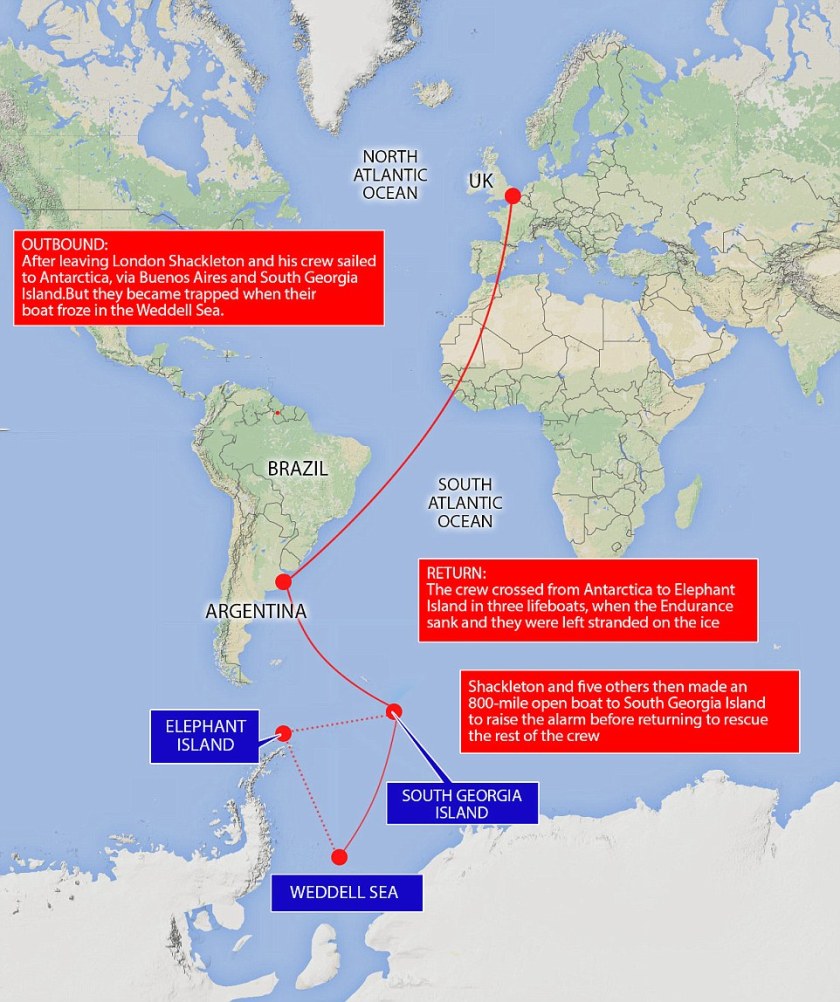

The trio arrived at the Stromness whaling station on May 20. They must have been a sight, with thick ice encrusting their long, filthy beards, and saltwater-soaked sealskin clothing rotting from their bodies. The first people they came across were children, who ran in fright at the sight of them.

The trio arrived at the Stromness whaling station on May 20. They must have been a sight, with thick ice encrusting their long, filthy beards, and saltwater-soaked sealskin clothing rotting from their bodies. The first people they came across were children, who ran in fright at the sight of them.

Welansky was a tough boss, maniacally determined not to be cheated out of a tab or a cover charge. He locked exit doors, concealed others with draperies, and even bricked up one emergency exit. Nobody was going to leave Cocoanut Grove without paying up.

Welansky was a tough boss, maniacally determined not to be cheated out of a tab or a cover charge. He locked exit doors, concealed others with draperies, and even bricked up one emergency exit. Nobody was going to leave Cocoanut Grove without paying up. The decorations ignited immediately, fire racing so fast along the satin canopy, that wooden strips suspending it from the ceiling remained unscathed.

The decorations ignited immediately, fire racing so fast along the satin canopy, that wooden strips suspending it from the ceiling remained unscathed. Today, fire codes require revolving doors to be flanked by doors on either side, but that wasn’t the case in 1942. Desperate to escape, patrons packed the single revolving door, their bodies jamming it so tightly that firefighters later had to dismantle the entire frame.

Today, fire codes require revolving doors to be flanked by doors on either side, but that wasn’t the case in 1942. Desperate to escape, patrons packed the single revolving door, their bodies jamming it so tightly that firefighters later had to dismantle the entire frame. The most striking story of survival that night, was that of 21-year old Coast Guardsman Clifford Johnson, who returned to the nightclub no fewer than four times in search of his date, Estelle Balkan. He didn’t know that she had safely escaped, and each time Johnson returned with another unconscious smoke victim in his arms. Johnson himself was on fire his last time out, when he collapsed onto the sidewalk, still ablaze.

The most striking story of survival that night, was that of 21-year old Coast Guardsman Clifford Johnson, who returned to the nightclub no fewer than four times in search of his date, Estelle Balkan. He didn’t know that she had safely escaped, and each time Johnson returned with another unconscious smoke victim in his arms. Johnson himself was on fire his last time out, when he collapsed onto the sidewalk, still ablaze.

Barney Welansky was tried and convicted on 19 counts of manslaughter, and sentenced to 12-15 years. Maurice Tobin, by then Governor, released him after four, his body ravaged with cancer. Welansky died 9 weeks later. Stanley Tomaszewski was exonerated. It wasn’t he who had placed all those flammable decorations, but the bus boy was treated like a Jonah, for the rest of his life.

Barney Welansky was tried and convicted on 19 counts of manslaughter, and sentenced to 12-15 years. Maurice Tobin, by then Governor, released him after four, his body ravaged with cancer. Welansky died 9 weeks later. Stanley Tomaszewski was exonerated. It wasn’t he who had placed all those flammable decorations, but the bus boy was treated like a Jonah, for the rest of his life.

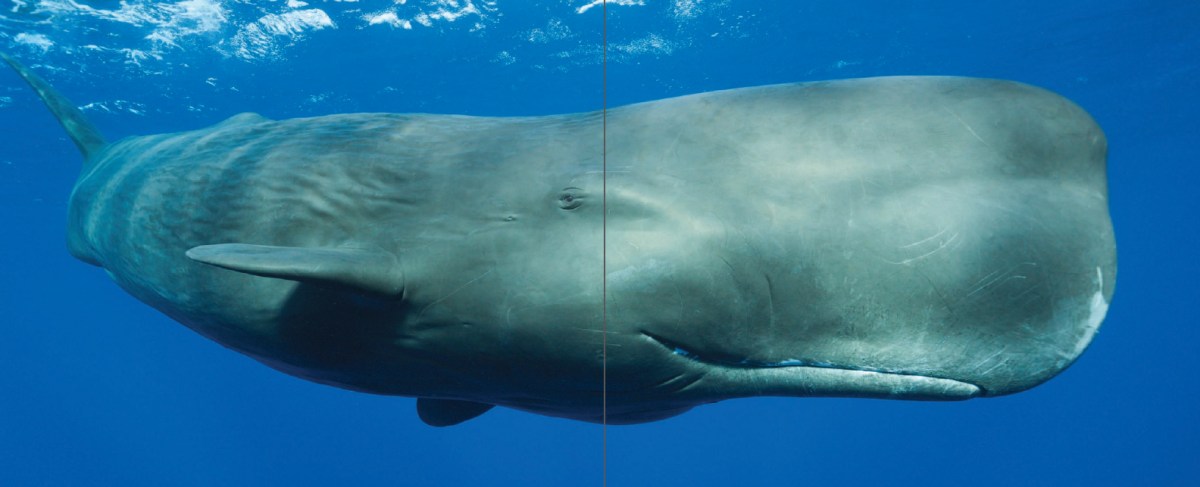

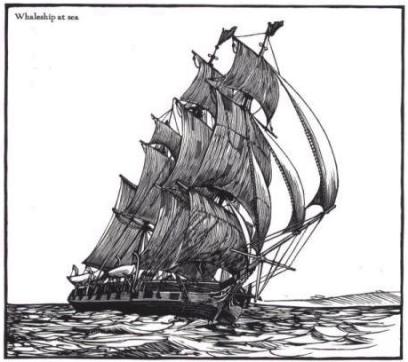

Essex sailed down the coast of South America, rounding the Horn and entering the Pacific Ocean. They heard that the whaling grounds near Chile and Peru were exhausted, so they sailed for the “offshore grounds”, almost 2,000 miles from the nearest land.

Essex sailed down the coast of South America, rounding the Horn and entering the Pacific Ocean. They heard that the whaling grounds near Chile and Peru were exhausted, so they sailed for the “offshore grounds”, almost 2,000 miles from the nearest land.

Captain George Pollard’s boat was the first to make it back, and he stared in disbelief. “My God, Mr. Chase, what is the matter?” he asked. “We have been stove by a whale” came the reply.

Captain George Pollard’s boat was the first to make it back, and he stared in disbelief. “My God, Mr. Chase, what is the matter?” he asked. “We have been stove by a whale” came the reply. They never knew that this was Henderson Island, only 104 miles from Pitcairn Island, where survivors from the 1789 Mutiny on HMS Bounty had managed to survive for the past 36 years.

They never knew that this was Henderson Island, only 104 miles from Pitcairn Island, where survivors from the 1789 Mutiny on HMS Bounty had managed to survive for the past 36 years.

The men who built it used to suck lemons on the job site, to keep from becoming seasick. It was probably one of these “boomers” who first noticed how the bridge rippled in the wind. Someone called it “Galloping Gertie”, and the name stuck.

The men who built it used to suck lemons on the job site, to keep from becoming seasick. It was probably one of these “boomers” who first noticed how the bridge rippled in the wind. Someone called it “Galloping Gertie”, and the name stuck. The bridge was bucking so violently that at times, one sidewalk rose as high as 28’ above its opposite.

The bridge was bucking so violently that at times, one sidewalk rose as high as 28’ above its opposite.

Indianapolis made her delivery on July 26, arriving at Guam two days later and then heading for Leyte to take part in the planned invasion of Japan. She was expected to arrive on the 31st.

Indianapolis made her delivery on July 26, arriving at Guam two days later and then heading for Leyte to take part in the planned invasion of Japan. She was expected to arrive on the 31st.

An emergency landing on open ocean is not an option with such a large aircraft. It would have broken up on impact with the probable loss of all hands. Descending rapidly, the crew would have jettisoned everything they could lay hands on, to reduce weight. Non-essential equipment would have gone first, then excess fuel, but it wasn’t enough. With only 2,500ft and losing altitude, there was no choice left but to jettison those atomic bombs.

An emergency landing on open ocean is not an option with such a large aircraft. It would have broken up on impact with the probable loss of all hands. Descending rapidly, the crew would have jettisoned everything they could lay hands on, to reduce weight. Non-essential equipment would have gone first, then excess fuel, but it wasn’t enough. With only 2,500ft and losing altitude, there was no choice left but to jettison those atomic bombs.

Temporary morgues were set up in area buildings for the identification of the dead; including what is now the sound stage for The Oprah Winfrey Show, Harpo Studios, and the location of the Chicago Hard Rock Cafe.

Temporary morgues were set up in area buildings for the identification of the dead; including what is now the sound stage for The Oprah Winfrey Show, Harpo Studios, and the location of the Chicago Hard Rock Cafe.

You must be logged in to post a comment.