“Sitzkrieg”. “Phony War”. Those were the terms used to describe the September ‘39 to May 1940 period, when neither side of what was to become the second world war, was yet prepared to launch a major ground war against the other.

The start of the “Great War” twenty-five years earlier, was different. Had you been alive in August 1914, you would have witnessed what might be described as the simultaneous detonation of a continent. France alone suffered 140,000 casualties over the four day “Battle of the Frontiers”, where the River Sambre met the Meuse. 27,000 Frenchmen died in a single day, August 22, in the forests of the Ardennes and Charleroi. The British Expeditionary Force escaped annihilation on August 22-23, only by the intervention of mythic angels, at a place called Mons.

In the East, a Russian army under General Alexander Samsonov was encircled and so thoroughly shattered at Tannenberg, that German machine gunners were driven to insanity at the damage inflicted by their own guns, on the milling and helpless masses of Russian soldiers. Only 10,000 of the original 150,000 escaped death, destruction or capture. Samsonov himself walked into the woods, and shot himself.

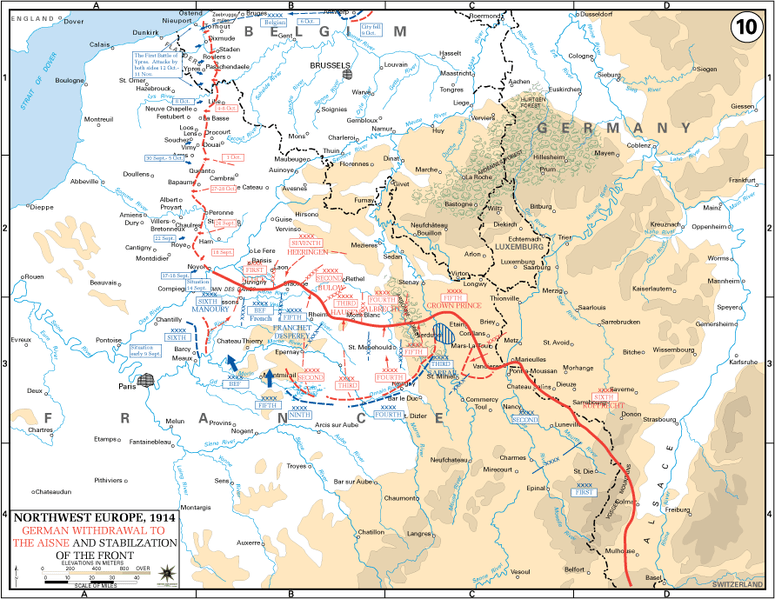

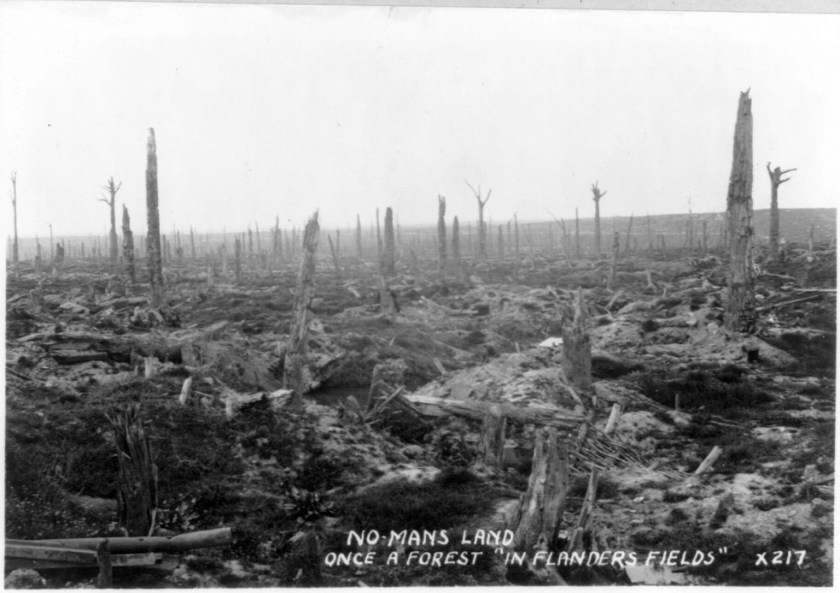

The “Race to the Sea” of mid-September to late October was more a series of leapfrog movements and running combat, in which the adversaries tried to outflank one another. It would be some of the last major movement of the Great War, ending in the apocalypse of Ypres, in which 75,000 from all sides lost their lives. All along a 450-mile front, millions of soldiers dug into the ground to shelter themselves from what Private Ernst Jünger later called a “Storm of Steel”.

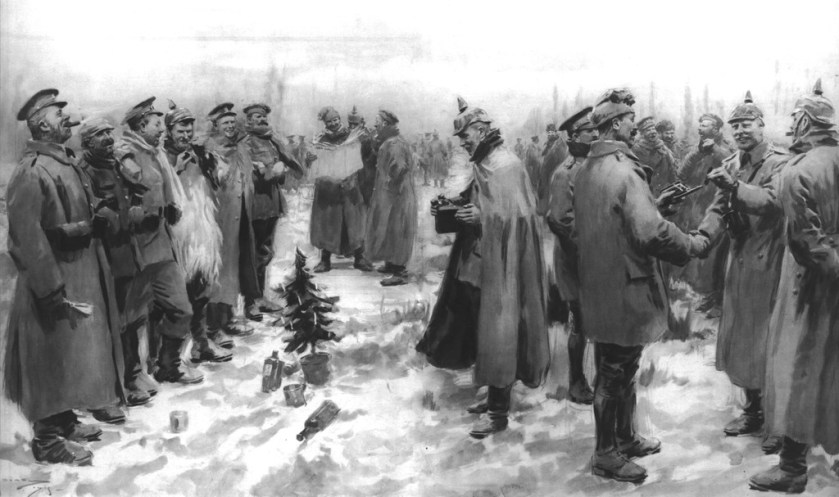

On the Western Front, it rained for much of November and December that first year. The no man’s land between British and German trenches was a wasteland of mud and barbed wire. Christmas Eve, 1914 dawned cold and clear. The frozen ground allowed men to move about for the first time in weeks. That evening, English soldiers heard singing. The low sound of a Christmas carol, drifting across no man’s land…Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht…Silent Night.

On the Western Front, it rained for much of November and December that first year. The no man’s land between British and German trenches was a wasteland of mud and barbed wire. Christmas Eve, 1914 dawned cold and clear. The frozen ground allowed men to move about for the first time in weeks. That evening, English soldiers heard singing. The low sound of a Christmas carol, drifting across no man’s land…Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht…Silent Night.

The Tommies saw lanterns and small fir trees. Messages were shouted along the trenches. In some places, British soldiers and even a few French joined in the Germans’ songs. Alles schläft; einsam wacht, Nur das traute hochheilige Paar. Holder Knabe im lockigen Haar…

The following day was Christmas, 1914. A few German soldiers emerged from their trenches at the first light of dawn, approaching the Allies across no man’s land and calling out “Merry Christmas” in the native tongue of their adversaries. Allied soldiers first thought it was a trick, but these Germans were unarmed, standing out in the open where they could be shot on a whim. Tommies soon climbed out of their own trenches, shaking hands with the Germans and exchanging gifts of cigarettes, food and souvenirs. In at least one sector, enemy soldiers played a friendly game of soccer.

Captain Bruce Bairnsfather later wrote: “I wouldn’t have missed that unique and weird Christmas Day for anything. … I spotted a German officer, some sort of lieutenant I should think, and being a bit of a collector, I intimated to him that I had taken a fancy to some of his buttons. … I brought out my wire clippers and, with a few deft snips, removed a couple of his buttons and put them in my pocket. I then gave him two of mine in exchange. … The last I saw was one of my machine gunners, who was a bit of an amateur hairdresser in civil life, cutting the unnaturally long hair of a docile Boche, who was patiently kneeling on the ground whilst the automatic clippers crept up the back of his neck.”

Captain Sir Edward Hulse Bart reported a sing-song which “ended up with ‘Auld lang syne’ which we all, English, Scots, Irish, Prussians, Wurttenbergers, etc, joined in. It was absolutely astounding, and if I had seen it on a cinematograph film I should have sworn that it was faked!”

Captain Sir Edward Hulse Bart reported a sing-song which “ended up with ‘Auld lang syne’ which we all, English, Scots, Irish, Prussians, Wurttenbergers, etc, joined in. It was absolutely astounding, and if I had seen it on a cinematograph film I should have sworn that it was faked!”

Nearly 100,000 Allied and German troops were involved in the unofficial ceasefire of Christmas 1914, lasting in some sectors until New Year’s Day.

A few tried to replicate the event the following year, but there were explicit orders preventing it. Captain Llewelyn Wyn Griffith recorded that after a night of exchanging carols, dawn on Christmas Day 1915 saw a “rush of men from both sides … [and] a feverish exchange of souvenirs” before the men were quickly called back by their officers.

One German unit tried to leave their trenches under a flag of truce on Easter Sunday 1915, but were warned off by the British opposite them.

German soldier Richard Schirrmann wrote in December 1915, “When the Christmas bells sounded in the villages of the Vosges behind the lines …. something fantastically unmilitary occurred. German and French troops spontaneously made peace and ceased hostilities; they visited each other through disused trench tunnels, and exchanged wine, cognac and cigarettes for Westphalian black bread, biscuits and ham. This suited them so well that they remained good friends even after Christmas was over”.

Some will tell you, the bitterness engendered by continuous fighting made such fraternization all but impossible. Yet, there are those who believe that soldiers never stopped fraternizing with their opponents, at least during the Christmas season. Heavy artillery, machine gun, and sniper fire were all intensified in anticipation of Christmas truces, minimizing such events in a way that kept them out of the history books.

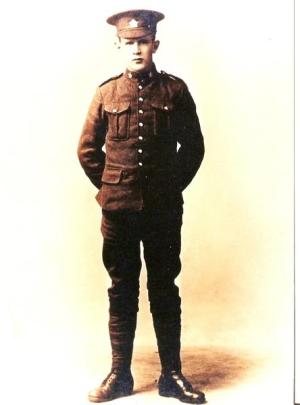

Even so, evidence exists of a small Christmas truce in 1916, though little is known of it. 23-year-old Private Ronald MacKinnon of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, wrote home about German and Canadian soldiers reaching across battle lines near Arras, sharing Christmas greetings and trading gifts. “I had quite a good Christmas considering I was in the front line”, he wrote. “Christmas Eve was pretty stiff, sentry-go up to the hips in mud of course. … We had a truce on Christmas Day and our German friends were quite friendly. They came over to see us and we traded bully beef for cigars”. The letter ends with Private MacKinnon noting that “Christmas was ‘tray bon’, which means very good.”

Private Ronald MacKinnon of Toronto Ontario, Regimental number 157629, was killed barely three months later on April 9, 1917, during the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

The Man He Killed

by Thomas Hardy

Had he and I but met

By some old ancient inn,

We should have set us down to wet

Right many a nipperkin!

But ranged as infantry,

And staring face to face,

I shot at him as he at me,

And killed him in his place.

I shot him dead because–

Because he was my foe,

Just so: my foe of course he was;

That’s clear enough; although

He thought he’d ‘list, perhaps,

Off-hand like–just as I–

Was out of work–had sold his traps–

No other reason why.

Yes; quaint and curious war is!

You shoot a fellow down

You’d treat, if met where any bar is,

Or help to half a crown.

The celebrity novelist enjoyed the finest sights of Boston and New York, and took in a steamship ride, down the Mississippi. He visited one of the great wonders of the natural world, the spectacular Niagara Falls.

The celebrity novelist enjoyed the finest sights of Boston and New York, and took in a steamship ride, down the Mississippi. He visited one of the great wonders of the natural world, the spectacular Niagara Falls.

For the American colonies, the conflict took the form of the French and Indian War. Across the “pond”, the never-ending succession of English wars meant that, not only were colonists left alone to run their own affairs, but individual colonists learned an interdependence of one upon another, resulting in significant economic growth during every decade of the 1700s.

For the American colonies, the conflict took the form of the French and Indian War. Across the “pond”, the never-ending succession of English wars meant that, not only were colonists left alone to run their own affairs, but individual colonists learned an interdependence of one upon another, resulting in significant economic growth during every decade of the 1700s.

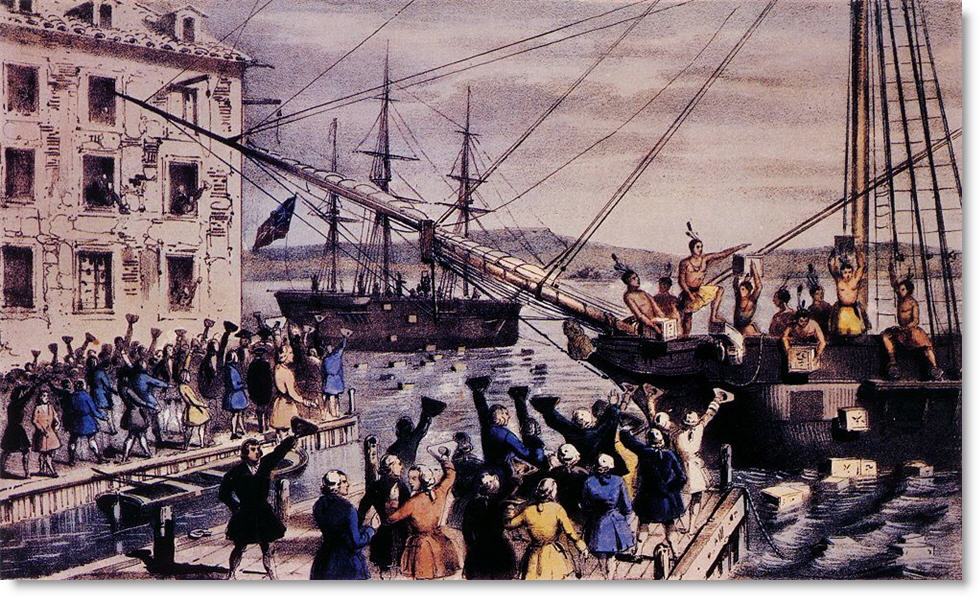

7,000 gathered at Old South Meeting House on December 16th, 1773, the last day of deadline, for Dartmouth’s cargo. Royal Governor Hutchinson held his ground, refusing the vessel permission to leave. Adams announced that “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

7,000 gathered at Old South Meeting House on December 16th, 1773, the last day of deadline, for Dartmouth’s cargo. Royal Governor Hutchinson held his ground, refusing the vessel permission to leave. Adams announced that “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would remember the events of that day as “

Boston by British troops. Minutemen clashed with “Lobster backs” a few months later, on April 19, 1775. When it was over, eight Lexington men lay dead or dying, another ten wounded. One British soldier was wounded. No one alive today knows who fired the first shot at Lexington Green. History would remember the events of that day as “

NAAFI personnel serving on ships are assigned to duty stations and wear uniforms, while technically remaining civilians.

NAAFI personnel serving on ships are assigned to duty stations and wear uniforms, while technically remaining civilians.

Early versions of the German “Enigma” code were broken as early as 1932, thanks to cryptanalysts of the Polish Cipher Bureau, and French spy Hans Thilo Schmidt.

Early versions of the German “Enigma” code were broken as early as 1932, thanks to cryptanalysts of the Polish Cipher Bureau, and French spy Hans Thilo Schmidt. The beginning of the end of darkness came to an end on October 30, when a ship’s cook climbed up that conning ladder. Code sheets allowed British cryptanalysts to attack the “Triton” key used by the U-boat service. It would not be long, before the U-boats themselves, were under attack.

The beginning of the end of darkness came to an end on October 30, when a ship’s cook climbed up that conning ladder. Code sheets allowed British cryptanalysts to attack the “Triton” key used by the U-boat service. It would not be long, before the U-boats themselves, were under attack.

There was no panic, Londoners are quite accustomed to the fog, but this one was different. Over the weeks that followed, public health authorities estimated that 4,000 people had died as a direct result of the smog by December 8, and another 100,000 made permanently ill. Research pointed to another 6,000 losing their lives in the following months, as a result of the event.

There was no panic, Londoners are quite accustomed to the fog, but this one was different. Over the weeks that followed, public health authorities estimated that 4,000 people had died as a direct result of the smog by December 8, and another 100,000 made permanently ill. Research pointed to another 6,000 losing their lives in the following months, as a result of the event.

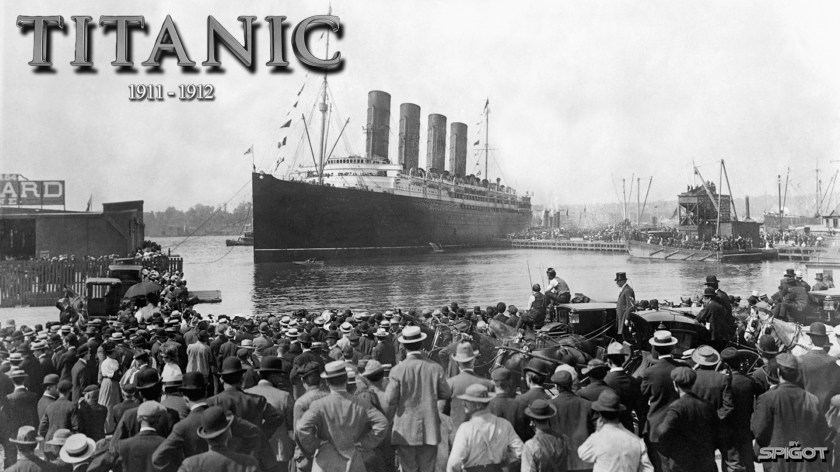

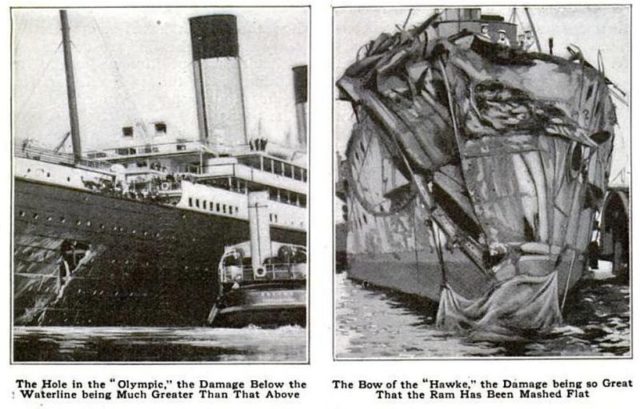

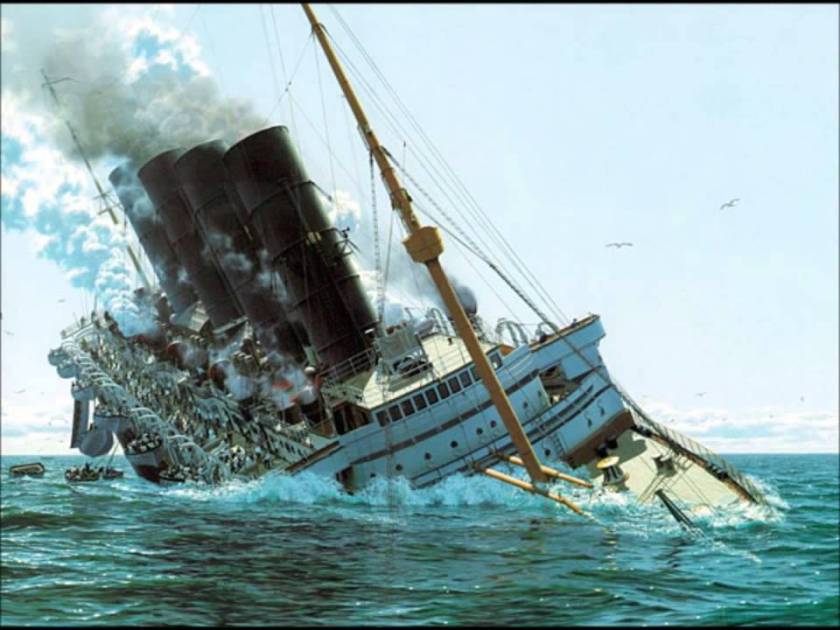

The ship was built to survive flooding in four watertight compartments. The iceberg had opened five. As Titanic began to lower at the bow, it soon became clear that the ship was doomed.

The ship was built to survive flooding in four watertight compartments. The iceberg had opened five. As Titanic began to lower at the bow, it soon became clear that the ship was doomed.

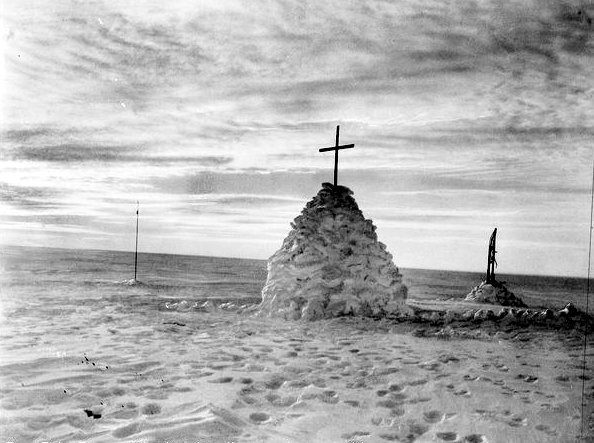

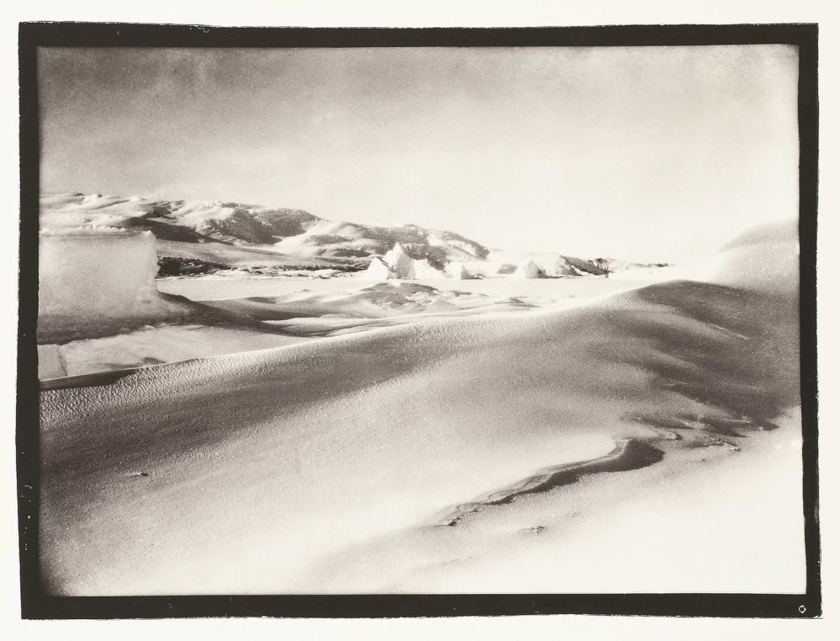

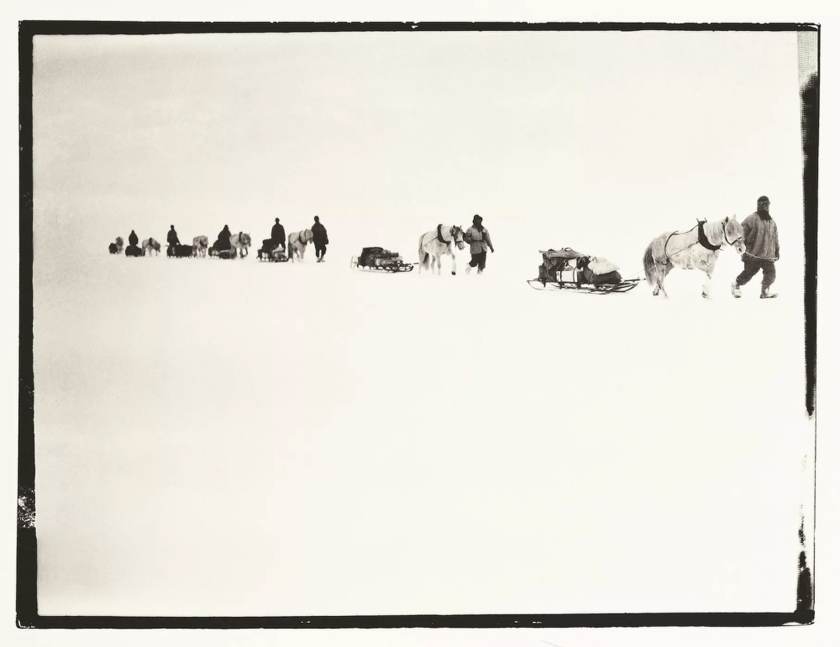

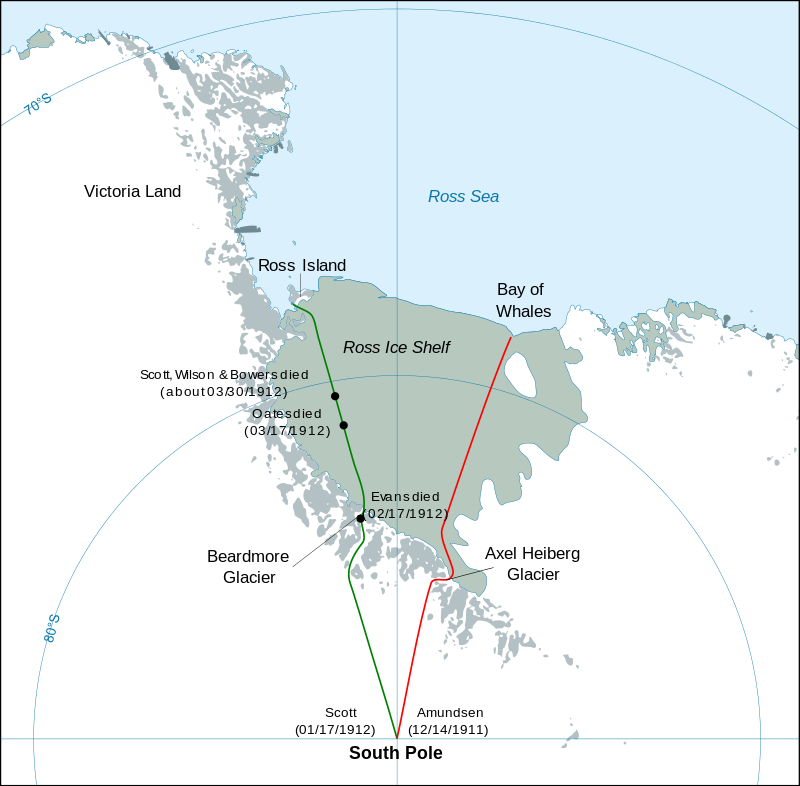

As long as he could remember, Roald Amundsen wanted to be an explorer. As a boy, he would read about the doomed Franklin Arctic Expedition, of 1848. A sixteen-year-old Amundsen took inspiration from Fridtjof Nansen’s epic crossing of Greenland, in 1888.

As long as he could remember, Roald Amundsen wanted to be an explorer. As a boy, he would read about the doomed Franklin Arctic Expedition, of 1848. A sixteen-year-old Amundsen took inspiration from Fridtjof Nansen’s epic crossing of Greenland, in 1888. In the Royal Navy, limited opportunities for career advancement were eagerly sought after, by any number of ambitious officers. Home on leave in 1899, Scott chanced once again to meet the now-knighted “Sir” Clements Markham, and learned of an impending RGS Antarctic expedition, aboard the barque-rigged auxiliary steamship, RRS Discovery. What passed between the two went unrecorded but, a few days later, Scott showed up at the Markham residence, and volunteered to lead the expedition.

In the Royal Navy, limited opportunities for career advancement were eagerly sought after, by any number of ambitious officers. Home on leave in 1899, Scott chanced once again to meet the now-knighted “Sir” Clements Markham, and learned of an impending RGS Antarctic expedition, aboard the barque-rigged auxiliary steamship, RRS Discovery. What passed between the two went unrecorded but, a few days later, Scott showed up at the Markham residence, and volunteered to lead the expedition.

At first in no hurry to sign up, he even considered joining the French Army before returning home to England, to enlist in the Artists Rifles Training Corps, in October 1915.

At first in no hurry to sign up, he even considered joining the French Army before returning home to England, to enlist in the Artists Rifles Training Corps, in October 1915. After this experience, soldiers reported him behaving strangely. Owen was diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia or shell shock, what we now understand to be Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh, for treatment.

After this experience, soldiers reported him behaving strangely. Owen was diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia or shell shock, what we now understand to be Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh, for treatment. Owen continued to write through his period of convalescence, his fame as author and poet growing through the late months of 1917 and into March of the following year. Supporters requested non-combat postings on his behalf, but such requests were turned down. It’s unlikely he would have accepted them, anyway. His letters reveal a deep sense of obligation, an intention to return to the front to be part of and to tell the story of the common man, thrust by his government into uncommon conditions.

Owen continued to write through his period of convalescence, his fame as author and poet growing through the late months of 1917 and into March of the following year. Supporters requested non-combat postings on his behalf, but such requests were turned down. It’s unlikely he would have accepted them, anyway. His letters reveal a deep sense of obligation, an intention to return to the front to be part of and to tell the story of the common man, thrust by his government into uncommon conditions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.