She was about 5-feet tall when her parents moved to Washington, a mere wraith of a girl of 14 summers, as yet unable to tip the scales at 90 pounds. Her father Robert was a surveyor, come to the capital for a job in the cartography office.

Her brother Robert headed south to Arkansas, to join with Woodruff’s Battery in service to the Confederate Army. The year was 1861. The District of Columbia was the capital in name only, of a nation at war with itself.

The elder Robert took ill and times got tough for the Ream family. Despite her diminutive stature, Lavinia Ellen, “Vinnie“ to friends and family, took a job to help with family finances. She was working in the dead letter office at the post office, one of the first women ever hired by the federal government.

Missouri Congressman James Rollins introduced Vinnie to sculptor Clark Mills in 1863, the artist who produced that statue of President Andrew Jackson, the one we’ve heard so much about recently, there in Lafayette square.

The artist was amused when the young girl remarked “I can do that myself” and handed her a pail of clay with an invitation to try. He was delighted when she returned a month later, this time with a surprisingly good likeness of an Indian Chieftain. It wasn’t long before she became Mills’ apprentice.

Stories spread concerning the remarkable abilities of this young artist. Vinnie’s talents blossomed and she left the post office to pursue her art, full time. Senators and Members of Congress were her subjects. Her faithful likeness of the glowering visage of that fierce opponent of slavery Thaddeus Stevens, the Pennsylvania Republican Congressman who would one day lead the impeachment effort against President Andrew Johnson, earned her an important and powerful ally.

It must have been an exciting time for a young girl in Washington DC, the horse-drawn ambulances, the ever-present blue-clad soldiers and more than anything, the raw-boned figure of the President of the United States, his carriage invariably accompanied by a squadron of brightly caparisoned, mounted Army officers. Vinnie was interested in the figure of Abraham Lincoln. The desire to sculpt the man’s likeness blossomed to an obsession as the titanic weight of office and crushing grief following the death of Lincoln’s 12-year-old son Willy, seemingly etched themselves across the President’s face.Raised as she was on the western prairies of Wisconsin, Kansas, and Missouri, Vinnie was unacquainted with the “way things were done” in the nation’s capital. Petite, quick with a smile and not a little ambitious, she could often get to “yes” where others hadn’t so much as a chance.

So it was in 1864, Vinnie was granted permission which would have been denied, to an older artist. She herself explained “Lincoln had been painted and modeled before, and when friends of mine first asked him to sit for me he dismissed them wearily until he was told that I was but an ambitious girl, poor and obscure. … Had I been the greatest sculptor in the world I am sure that I would have been refused.”

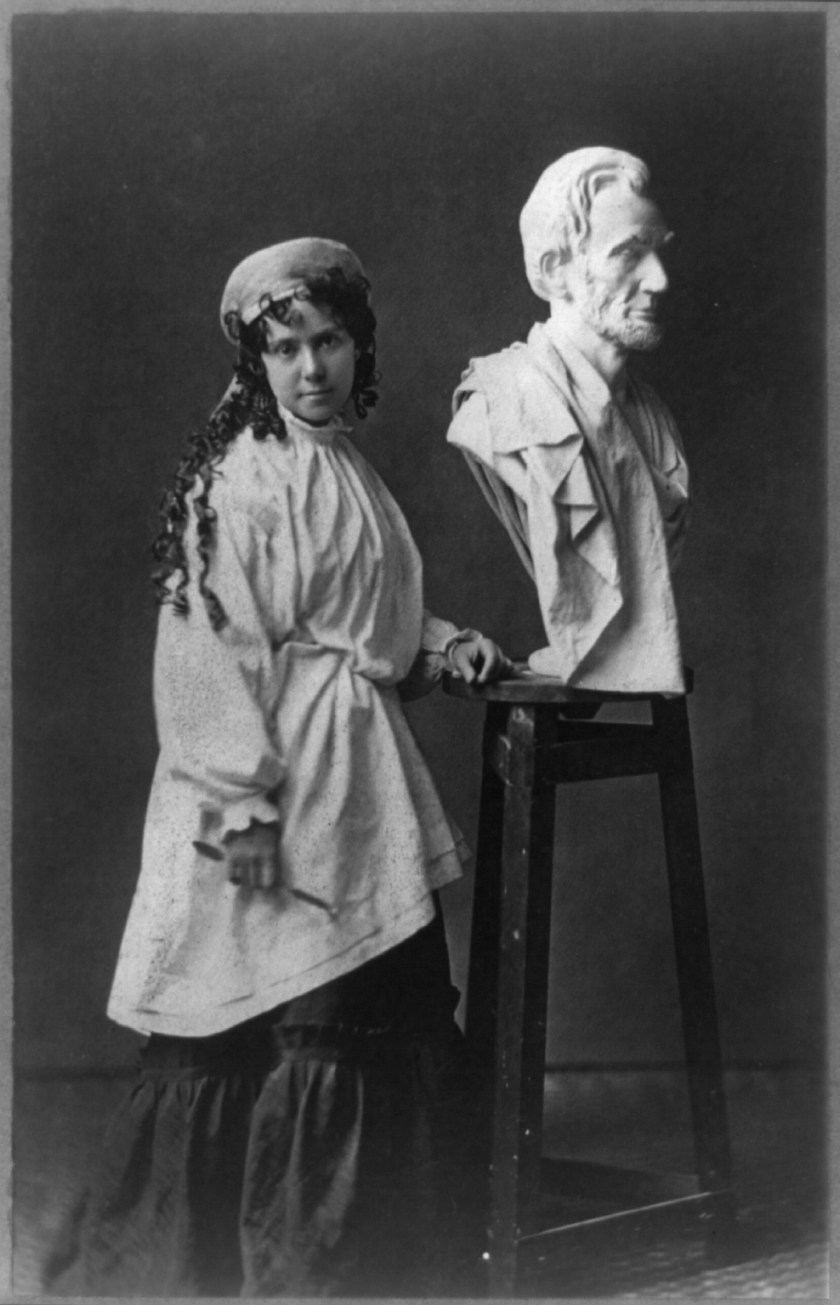

Every day for five months, Vinnie Ream had a private half-hour with the President of the United States, the two speaking but infrequently as she set her hands about the work. She was performing the final touches on the bust you see below, the morning of April 14, 1865. General Robert. E. Lee had surrendered to General Ulysses Grant only five days earlier. The most catastrophic war in American history was winding to a close. That night, the President planned a welcome break from the cares of office, at a place called Ford’s theater.

A nation was stunned following the Lincoln assassination. Vinnie herself, prostrate at the death of her friend and hero.

There arose a movement in Congress, to honor the Great Man with a full-length statue, to be placed in the Rotunda of the Capitol. A competition would be held, to determine the artist. Washington was then as it is now, but Vinnie had learned a political lesson or two since those naive days of five years earlier. The petition attesting to her talents and worthiness for the project was signed by Andrew Johnson, Ulysses Grant, 31 Senators and 110 members of the House of Representatives.

Then as now, Washington was a “Swamp” and a cesspit for the venal and self-interested. Now grown to an attractive young woman, Vinnie Ream was not without critics. Kansas Senator Edmund Gibson Ross boarded with the Ream family during Johnson’s impeachment trial and cast the one vote absolving the President of “High Crimes and Misdemeanors”.

Then as now, Washington was a “Swamp” and a cesspit for the venal and self-interested. Now grown to an attractive young woman, Vinnie Ream was not without critics. Kansas Senator Edmund Gibson Ross boarded with the Ream family during Johnson’s impeachment trial and cast the one vote absolving the President of “High Crimes and Misdemeanors”.

Imagine how THAT must’ve sounded.

There were sleazy insinuations that she was a “lobbyist” or even a “Public Woman” (prostitute).

Newspaper columnist Mrs. Jane Grey Swisshelm sniffed about how Vinnie “carries the day” with members of Congress: “Miss .… Ream … is a young girl of about twenty who has been studying her art for a few months, never made a statue, has some plaster busts on exhibition, including her own, minus clothing to the waist, has a pretty face, long dark curls and plenty of them. … [She] sees members at their lodgings or in the reception room at the Capitol, urges her claims fluently and confidently, sits in the galleries in a conspicuous position and in her most bewitching dress, while those claims are being discussed on the floor, and nods and smiles as a member rises…”

One editor had the last word, however, printing Swisshelm’s column under the headline “A Homely Woman’s Opinion of a Pretty One.”

One editor had the last word, however, printing Swisshelm’s column under the headline “A Homely Woman’s Opinion of a Pretty One.”

Ouch.

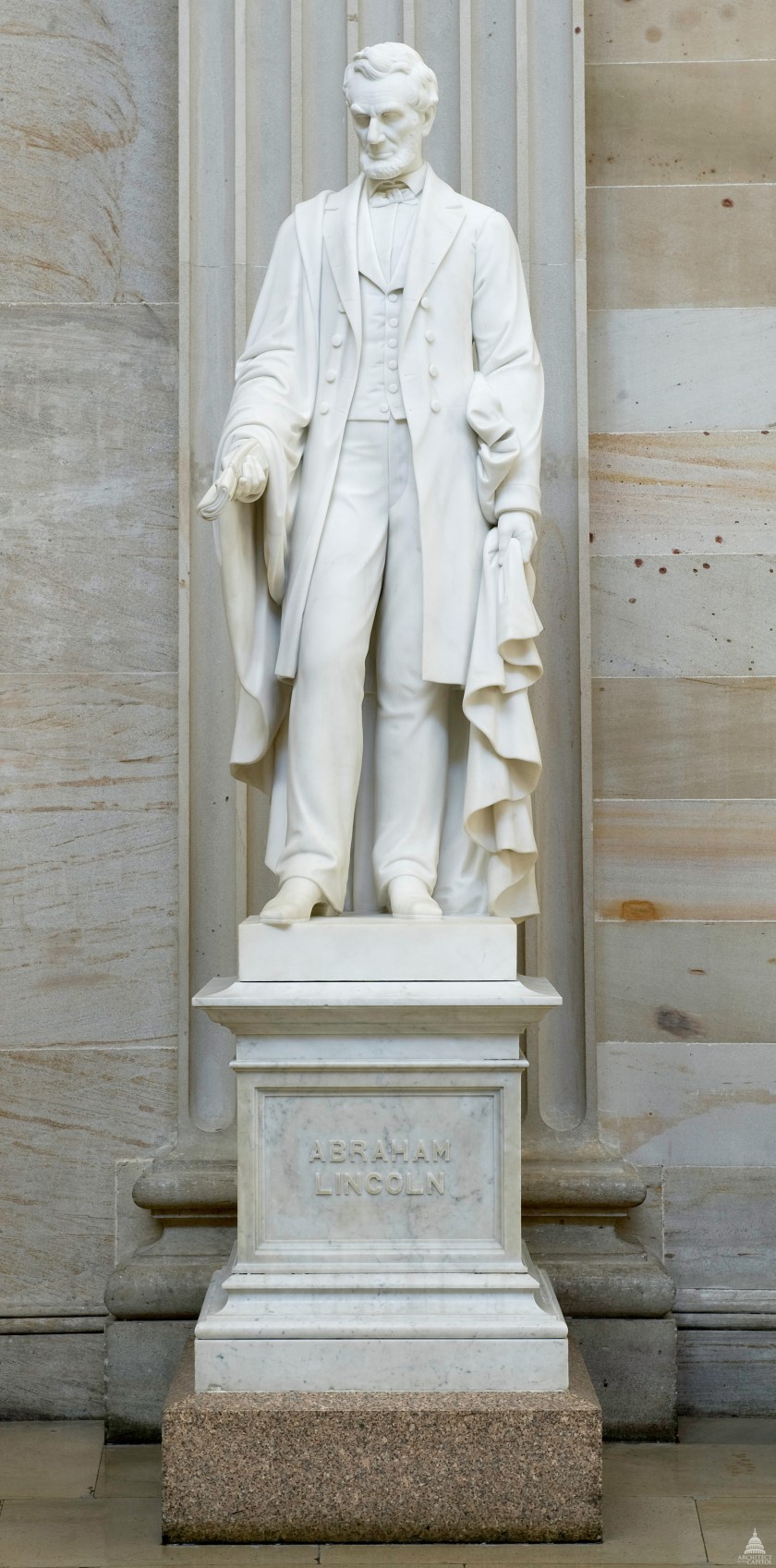

On this day in 1866, Vinnie Ream was awarded by vote of Congress, the commission to create a full-size statue of Abraham Lincoln. She was 18 years old, the first woman to receive a such a commission as an artist and the youngest of either sex, to create a statue for the United States government.

Even then, Vinnie was not without detractors. Michigan Senator Jacob Merritt Howard remarked, “Having in view the youth and inexperience of Miss Ream, and I will go further, and say, having in view her sex, I shall expect a complete failure in the execution of this work.”

Miss Lavinia Ream survived an effort to have her removed from her own studio by a vindictive House of Representatives, to enjoy the last word. Her depiction of the Great Emancipator sculpted from a flawless block of Carrara marble stands in the Rotunda of the Capitol where it is seen by millions of visitors, from that day to this.

Over the years there have been many Rosie the Riveters, the last of whom was Elinor Otto, who built aircraft for fifty years before being laid off at age ninety-five. Naomi Parker-Fraley knew she was the “first”, but that battle was a long lost cause until Dr. Kimble showed up at her door, in 2015. All those years, she had known. Now the world knew.

Over the years there have been many Rosie the Riveters, the last of whom was Elinor Otto, who built aircraft for fifty years before being laid off at age ninety-five. Naomi Parker-Fraley knew she was the “first”, but that battle was a long lost cause until Dr. Kimble showed up at her door, in 2015. All those years, she had known. Now the world knew.

At first in no hurry to sign up, he even considered joining the French Army before returning home to England, to enlist in the Artists Rifles Training Corps, in October 1915.

At first in no hurry to sign up, he even considered joining the French Army before returning home to England, to enlist in the Artists Rifles Training Corps, in October 1915. After this experience, soldiers reported him behaving strangely. Owen was diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia or shell shock, what we now understand to be Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh, for treatment.

After this experience, soldiers reported him behaving strangely. Owen was diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia or shell shock, what we now understand to be Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh, for treatment. Owen continued to write through his period of convalescence, his fame as author and poet growing through the late months of 1917 and into March of the following year. Supporters requested non-combat postings on his behalf, but such requests were turned down. It’s unlikely he would have accepted them, anyway. His letters reveal a deep sense of obligation, an intention to return to the front to be part of and to tell the story of the common man, thrust by his government into uncommon conditions.

Owen continued to write through his period of convalescence, his fame as author and poet growing through the late months of 1917 and into March of the following year. Supporters requested non-combat postings on his behalf, but such requests were turned down. It’s unlikely he would have accepted them, anyway. His letters reveal a deep sense of obligation, an intention to return to the front to be part of and to tell the story of the common man, thrust by his government into uncommon conditions.

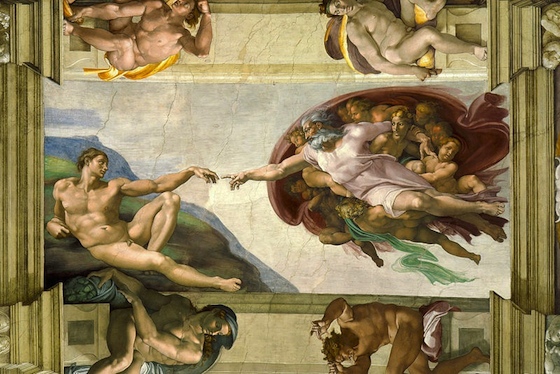

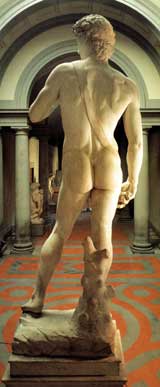

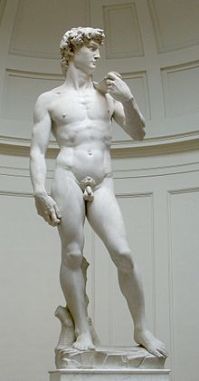

He was “Il Divino”, “The Divine One”, literally growing up with the hammer and chisel. He had a “Terribilità” about him, an awe-inspiring sense of grandeur which made him difficult to work with, but for which he was at the same time, widely admired and imitated. Michelangelo was that insufferably cocky kid who wasn’t bragging. He could deliver.

He was “Il Divino”, “The Divine One”, literally growing up with the hammer and chisel. He had a “Terribilità” about him, an awe-inspiring sense of grandeur which made him difficult to work with, but for which he was at the same time, widely admired and imitated. Michelangelo was that insufferably cocky kid who wasn’t bragging. He could deliver. The 17′, six-ton David was originally intended for the roof of the Florence Cathedral, but it wasn’t feasible to raise such an object that high. A committee including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli was formed to decide on an appropriate site for the statue. The committee chose the Piazza della Signoria outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the town hall of Florence.

The 17′, six-ton David was originally intended for the roof of the Florence Cathedral, but it wasn’t feasible to raise such an object that high. A committee including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli was formed to decide on an appropriate site for the statue. The committee chose the Piazza della Signoria outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the town hall of Florence.

Born on October 29, 1921 in New Mexico and brought up in Arizona, William Henry “Bill” Mauldin was part of what Tom Brokaw called, the “Greatest Generation”.

Born on October 29, 1921 in New Mexico and brought up in Arizona, William Henry “Bill” Mauldin was part of what Tom Brokaw called, the “Greatest Generation”. Mauldin developed two cartoon infantrymen, calling them “Willie and Joe”. He told the story of the war through their eyes. He became extremely popular within the enlisted ranks, while his humor tended to poke fun at the “spit & polish” of the officer corps. He even lampooned General George Patton one time, for insisting that his men to be clean shaven all the time. Even in combat.

Mauldin developed two cartoon infantrymen, calling them “Willie and Joe”. He told the story of the war through their eyes. He became extremely popular within the enlisted ranks, while his humor tended to poke fun at the “spit & polish” of the officer corps. He even lampooned General George Patton one time, for insisting that his men to be clean shaven all the time. Even in combat. Mauldin later told an interviewer, “I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn’t like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes”.

Mauldin later told an interviewer, “I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn’t like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes”. Bill Mauldin drew Willie & Joe for last time in 1998, for inclusion in Schulz’ Veteran’s Day Peanuts strip. Schulz had long described Mauldin as his hero. He signed that final strip Schulz, as always, and added “and my Hero“. Bill Mauldin’s signature, appears underneath.

Bill Mauldin drew Willie & Joe for last time in 1998, for inclusion in Schulz’ Veteran’s Day Peanuts strip. Schulz had long described Mauldin as his hero. He signed that final strip Schulz, as always, and added “and my Hero“. Bill Mauldin’s signature, appears underneath.

a nostalgic period looking back to the Classical age. Whatever it was, the 15th and 16th centuries produced some of the most spectacularly gifted artists, in history.

a nostalgic period looking back to the Classical age. Whatever it was, the 15th and 16th centuries produced some of the most spectacularly gifted artists, in history.

The massive block of Carrara marble was quarried in 1466, nine years before Michelangelo was born. The “David” commission was given to artist Agostino di Duccio that same year. So difficult was this particular marble block that he never got beyond roughing out the legs and draperies. Antonio Rossellino took a shot at it 10 years later, but he didn’t get much farther.

The massive block of Carrara marble was quarried in 1466, nine years before Michelangelo was born. The “David” commission was given to artist Agostino di Duccio that same year. So difficult was this particular marble block that he never got beyond roughing out the legs and draperies. Antonio Rossellino took a shot at it 10 years later, but he didn’t get much farther. Cathedral, but it wasn’t feasible to raise such an object that high. A committee including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli was formed to decide on an appropriate site for the statue. The commitee chose the Piazza della Signoria outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the town hall of Florence.

Cathedral, but it wasn’t feasible to raise such an object that high. A committee including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli was formed to decide on an appropriate site for the statue. The commitee chose the Piazza della Signoria outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the town hall of Florence.

You must be logged in to post a comment.