The whaleship Essex set sail from Nantucket in August 1819, the month when Herman Melville was born. The 21 man crew expected to spend 2-3 years hunting sperm whales, filling the ship’s hold with oil before returning to split the profits of the voyage.

Essex sailed down the coast of South America, rounding the Horn and entering the Pacific Ocean. They heard that the whaling grounds near Chile and Peru were exhausted, so they sailed for the “offshore grounds”, almost 2,000 miles from the nearest land.

Essex sailed down the coast of South America, rounding the Horn and entering the Pacific Ocean. They heard that the whaling grounds near Chile and Peru were exhausted, so they sailed for the “offshore grounds”, almost 2,000 miles from the nearest land.

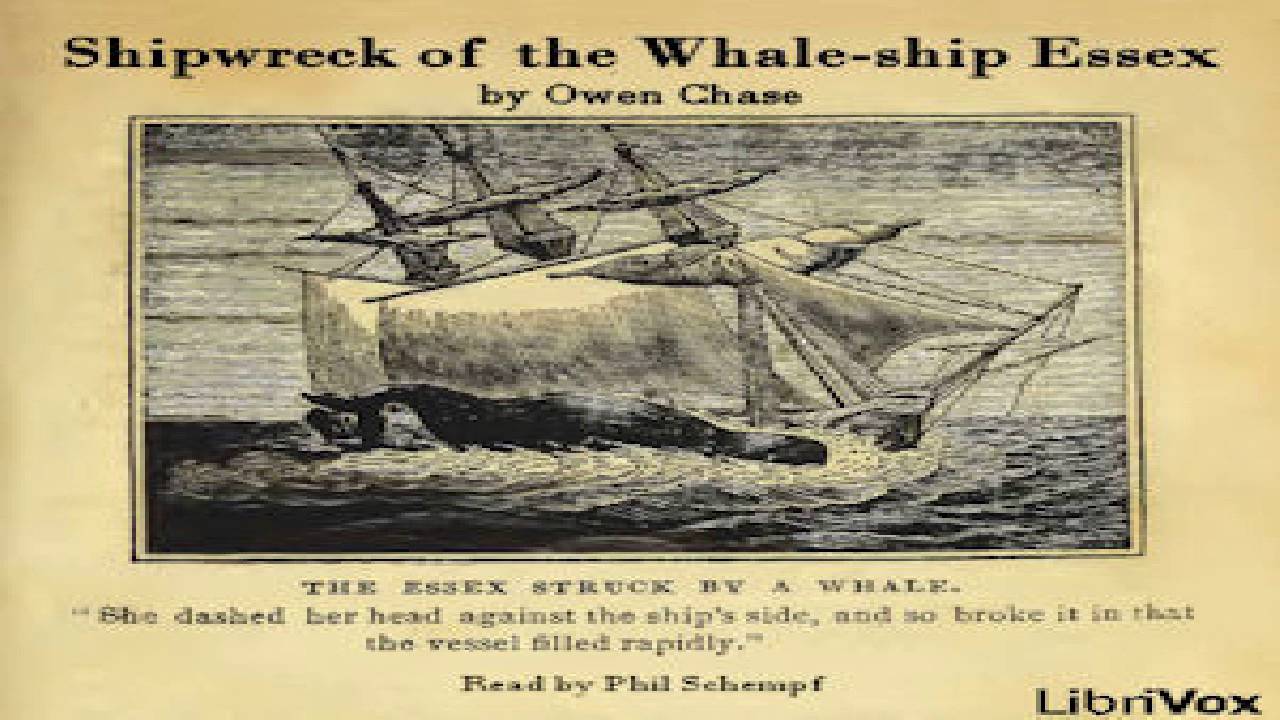

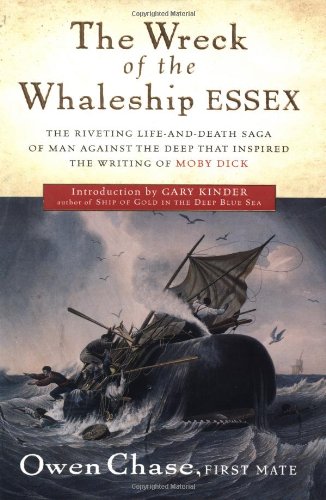

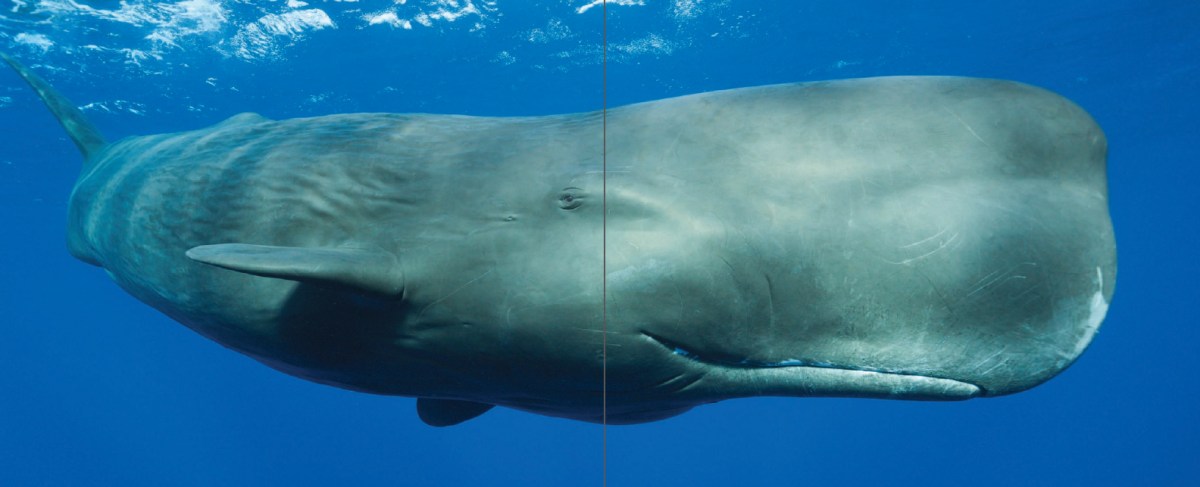

They were there on November 20, 1820, with two of their three boats out hunting whales. The lookout spotted a huge bull sperm whale, much larger than normal, estimated at 85 feet long and 80 tons. He was behaving oddly, lying motionless on the surface with his head facing the ship. In moments the whale began to move, picking up speed as he charged the ship. Never in the history of the whale fishery had a whale been known to attack a ship unprovoked. This one hit the port side so hard that it shook the ship.

The huge animal seemed dazed by the impact, floating to the surface and resting by the ship’s side. He then turned and swam away for several hundred yards, before turning to resume his attack. He came in at the great speed of 24 knots according to First Mate Owen Chase, ramming the port bow and driving the stern into the water. Oak planking cracked and splintered as the whale worked his tail up and down, driving the 238-ton vessel backward. Essex had already started to go down when the whale broke off his attack, diving below the surface, never to return.

Captain George Pollard’s boat was the first to make it back, and he stared in disbelief. “My God, Mr. Chase, what is the matter?” he asked. “We have been stove by a whale” came the reply.

Captain George Pollard’s boat was the first to make it back, and he stared in disbelief. “My God, Mr. Chase, what is the matter?” he asked. “We have been stove by a whale” came the reply.

No force on earth could save the stricken whale ship. The crew divided into groups of seven and boarded the three boats. It wasn’t long before Essex sank out of sight and they were alone, stranded in 28′ open boats, and about as far from land as it was mathematically possible to be.

The whalers believed that cannibals inhabited the Marquesa islands, 1,200 miles to the west, so they headed south, parallel to the coast of South America. Before their ordeal was over, they themselves would become the cannibals.

With good winds, they might reach the coast of Chile in 56 days. They had taken enough rations to last 60, provided they were distributed at starvation levels, but most of it had been ruined by salt water. There was a brief reprieve in December, when the three small boats landed on a small island in the Pitcairn chain. There they were able to get their fill of birds, eggs, crabs, and peppergrass, but within a week the island was stripped clean. They decided to move on, except for three who refused to get back in the boats.

They never knew that this was Henderson Island, only 104 miles from Pitcairn Island, where survivors from the 1789 Mutiny on HMS Bounty had managed to survive for the past 36 years.

They never knew that this was Henderson Island, only 104 miles from Pitcairn Island, where survivors from the 1789 Mutiny on HMS Bounty had managed to survive for the past 36 years.

After two months at sea, the boats had long separated from one another. Starving men were beginning to die, and the survivors came to an unthinkable conclusion. They would have to eat their own dead.

When those were gone, the survivors drew lots to see who would die, that the others might live. Captain Pollard’s 17-year-old cousin Owen Coffin, whom he had sworn to protect, drew the black spot. Pollard protested, offering to take his place, but the boy declined. “No”, he said, “I like my lot as well as any other.” Again, lots were drawn to see who would be Coffin’s executioner. Owen’s friend, Charles Ramsdell, drew the black spot.

On February 18, the British whaleship Indian spotted a boat containing Owen Chase, Benjamin Lawrence and Thomas Nickerson. It was 90 days after Essex’ sinking. Five days later, the Nantucket whaleship Dauphin pulled alongside another boat, to find Captain Pollard and Charles Ramsdell inside. The pair was so far gone that they didn’t notice at first, gnawing on the bones of their comrades.

The three who were left on Henderson Island were later rescued. The third whaleboat was found beached on a Pacific island several years later, with four skeletons on board.

The Essex was the first ship recorded to have been sunk by a whale, though it would not be the last. The Pusie Hall was attacked in 1835. The Lydia and the Two Generals were both attacked by whales a year later, and the Pocahontas and the Ann Alexander were sunk by whales in 1850 and 1851.

31 years after the Essex sinking, a sailor turned novelist published his sixth volume, beginning it with the words, “Call me Ishmael”.

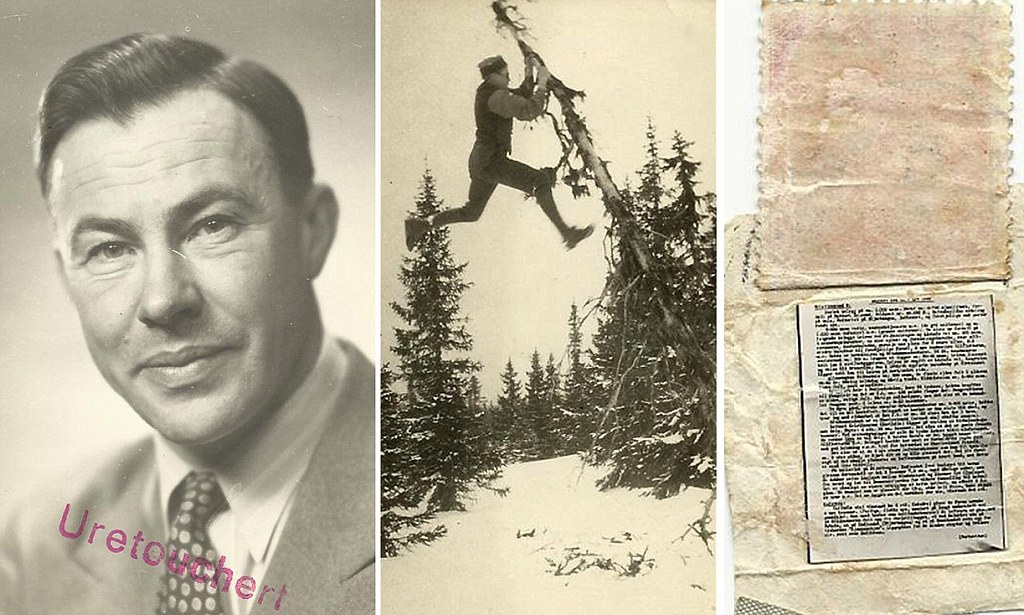

Another such man was his brother Sven, born this day, November 19, 1904.

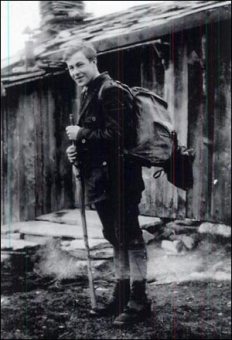

Another such man was his brother Sven, born this day, November 19, 1904. The Norwegian had barely an hour’s head start, and the Nazis couldn’t let this guy get away. He knew too much. Somme was pursued through streams and ravines as he worked his way into the mountains.

The Norwegian had barely an hour’s head start, and the Nazis couldn’t let this guy get away. He knew too much. Somme was pursued through streams and ravines as he worked his way into the mountains. Somme finally made it to neutral Sweden, where he was taken to England. There he met the exiled King of Norway, and the woman who would one day become his wife and mother of his three daughters, an English woman named Primrose.

Somme finally made it to neutral Sweden, where he was taken to England. There he met the exiled King of Norway, and the woman who would one day become his wife and mother of his three daughters, an English woman named Primrose.

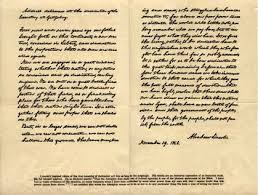

Lincoln signed, dated and titled the Bliss copy. This is the version inscribed on the South wall of the Lincoln Memorial.

Lincoln signed, dated and titled the Bliss copy. This is the version inscribed on the South wall of the Lincoln Memorial.

This was a time of big hair, when hair was piled high on top of the head, powdered, and augmented with the hair of servants and pets. The do was often adorned with fabric, ribbons or fruit, sometimes holding props like birdcages complete with stuffed birds, and even miniature frigates, under sail.

This was a time of big hair, when hair was piled high on top of the head, powdered, and augmented with the hair of servants and pets. The do was often adorned with fabric, ribbons or fruit, sometimes holding props like birdcages complete with stuffed birds, and even miniature frigates, under sail.

Sint Eustatius, known to locals as “Statia”, is a Caribbean island of 8.1 sq. miles in the northern Leeward Islands. Formerly part of the Netherlands Antilles, the island lies southeast of the Virgin Islands, immediately to the northwest of Saint Kitts.

Sint Eustatius, known to locals as “Statia”, is a Caribbean island of 8.1 sq. miles in the northern Leeward Islands. Formerly part of the Netherlands Antilles, the island lies southeast of the Virgin Islands, immediately to the northwest of Saint Kitts.

On the 16th of November, 1776, the Brig Andrew Doria sailed into Sint Eustatius’ principle anchorage in Oranje Bay. Flying the Continental Colors of the fledgling United States and commanded by Captain Isaiah Robinson, the Brig was there to obtain munitions and military supplies. Andrew Doria also carried a precious cargo, a copy of the Declaration of Independence.

On the 16th of November, 1776, the Brig Andrew Doria sailed into Sint Eustatius’ principle anchorage in Oranje Bay. Flying the Continental Colors of the fledgling United States and commanded by Captain Isaiah Robinson, the Brig was there to obtain munitions and military supplies. Andrew Doria also carried a precious cargo, a copy of the Declaration of Independence. Tradition dictated the firing of a salute in return, typically two guns fewer than that fired by the incoming vessel. Such an act carried meaning. The firing of a return salute was the overt recognition that a sovereign state had entered the harbor. Such a salute amounted to formal recognition of the independence of the 13 American colonies.

Tradition dictated the firing of a salute in return, typically two guns fewer than that fired by the incoming vessel. Such an act carried meaning. The firing of a return salute was the overt recognition that a sovereign state had entered the harbor. Such a salute amounted to formal recognition of the independence of the 13 American colonies. Rodney pretty much had his way. The census of 1790 shows 8,124 on the Dutch island nation. In 1950, the population stood at 790. It would take 150 years from Rodney’s departure, before tourism even began to restore the economic well-being of the tiny island.

Rodney pretty much had his way. The census of 1790 shows 8,124 on the Dutch island nation. In 1950, the population stood at 790. It would take 150 years from Rodney’s departure, before tourism even began to restore the economic well-being of the tiny island.

“Mainstream” white artists of the fifties and sixties often covered songs written by black artists. On April 6, 1963, an obscure rock & roll group out of Portland, Oregon covered the song, renting a recording studio for $50. They were The Kingsmen.

“Mainstream” white artists of the fifties and sixties often covered songs written by black artists. On April 6, 1963, an obscure rock & roll group out of Portland, Oregon covered the song, renting a recording studio for $50. They were The Kingsmen.

Strangely, the feds never interviewed Kingsmen lead singer Jack Ely, who probably could have saved them a lot of time.

Strangely, the feds never interviewed Kingsmen lead singer Jack Ely, who probably could have saved them a lot of time.

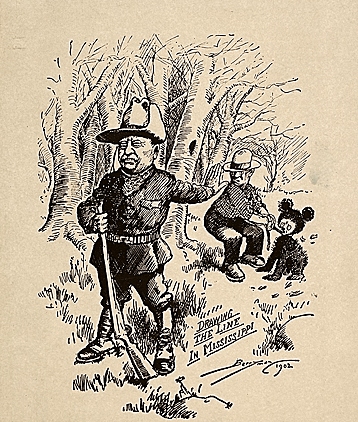

Roosevelt declined to shoot the animal, calling it “unsportsmanlike” to shoot a bound and wounded animal. Instead, he ordered the bear put down, putting an end to its pain.

Roosevelt declined to shoot the animal, calling it “unsportsmanlike” to shoot a bound and wounded animal. Instead, he ordered the bear put down, putting an end to its pain.

“The Wall” was dedicated on this day, November 13, 1982. 31 years later, we had come to pay respects to our Uncle Gary’s shipmates, their names inscribed on panel 24E, the 134 lost in the disaster aboard the Supercarrier USS

“The Wall” was dedicated on this day, November 13, 1982. 31 years later, we had come to pay respects to our Uncle Gary’s shipmates, their names inscribed on panel 24E, the 134 lost in the disaster aboard the Supercarrier USS

Officials discussed the matter with the Navy (it wasn’t every day that they had to remove 16,000 lbs of rotting whale meat) and someone came up with a bright idea. They would remove the carcass the same way they’d remove a huge boulder. They’d blow it up.

Officials discussed the matter with the Navy (it wasn’t every day that they had to remove 16,000 lbs of rotting whale meat) and someone came up with a bright idea. They would remove the carcass the same way they’d remove a huge boulder. They’d blow it up. The detonation tore through the whale, like a bullet passes through a pane of glass. Thousands of chunks of dead whale, large and small, soared through the air, landing on nearby buildings, houses and streets.

The detonation tore through the whale, like a bullet passes through a pane of glass. Thousands of chunks of dead whale, large and small, soared through the air, landing on nearby buildings, houses and streets.

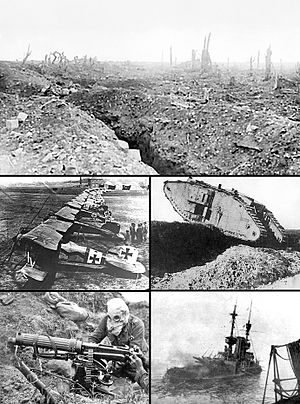

Imperial Germany, its army disintegrating in the field and threatened with revolution at home, had sent a peace delegation, headed by the 43-year-old German politician Matthias Erzberger.

Imperial Germany, its army disintegrating in the field and threatened with revolution at home, had sent a peace delegation, headed by the 43-year-old German politician Matthias Erzberger.

Foch informed Ertzberger that he had 72 hours in which to respond. “For God’s sake, Monsieur le Marechal”, responded the German, “do not wait for those 72 hours. Stop the hostilities this very day”. By this time, 2,250 were dying every day on the Western Front, yet the plea fell on deaf ears. Fighting would continue until the last minute of the last day.

Foch informed Ertzberger that he had 72 hours in which to respond. “For God’s sake, Monsieur le Marechal”, responded the German, “do not wait for those 72 hours. Stop the hostilities this very day”. By this time, 2,250 were dying every day on the Western Front, yet the plea fell on deaf ears. Fighting would continue until the last minute of the last day. At least 320 Americans were killed in those final six hours, 3,240 seriously wounded.

At least 320 Americans were killed in those final six hours, 3,240 seriously wounded. Matthias Erzberger was assassinated in 1921, for his role in the surrender. The “Stab in the Back” mythology destined to become Nazi propaganda, had already begun.

Matthias Erzberger was assassinated in 1921, for his role in the surrender. The “Stab in the Back” mythology destined to become Nazi propaganda, had already begun.

You must be logged in to post a comment.