For a variety of reasons, the eastern front of the “War to end all Wars” was a war of movement. Not so in the West. As early as October 1914, combatants burrowed into the ground like animals sheltering from what Private Ernst Jünger would come to call, the ‘Storm of Steel’.

Conditions in the trenches and dugouts must have defied description. You would have smelled the trenches long before you could see them. The collective funk of a million men and more, enduring the troglodyte existence of men who live in holes. Little but verminous scars in the earth teaming with rats and lice and swarming with flies. Time and again the shells churned up and pulverized the soil, the water and the shattered remnants of once-great forests, along with the bodies of the slain.

By the time the United States entered the ‘War to end all Wars’ in April, 1917, millions had endured three years of this existence. The first 14,000 Americans arrived ‘over there’ in June, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) forming on July 5. American troops fought the military forces of Imperial Germany alongside their British and French allies, others joining Italian forces in the struggle against the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

You couldn’t call the stuff these people lived in mud – it was more like a thick slime, a clinging, sucking ooze capable of swallowing grown men, even horses and mules, alive.

Captain Alexander Stewart wrote “Most of the night was spent digging men out of the mud. The only way was to put duck boards on each side of him and work at one leg: poking and pulling until the suction was relieved. Then a strong pull by three or four men would get one leg out, and work would begin on the other…He who had a corpse to stand or sit on, was lucky”.

Sir Launcelot Kiggell broke down in tears, on first seeing the horror of Paschendaele, . “Good God”, he said. “Did we really send men to fight in That?”

Unseen and unnoticed in times of such dread calamity, are the humanitarian workers. Those who tend to the physical and spiritual requirements and the countless small comforts, of those so afflicted.

Within days of the American declaration of war, Evangeline Booth, National Commander of the Salvation Army, responded, saying “The Salvationist stands ready, trained in all necessary qualifications in every phase of humanitarian work, and the last man will stand by the President for execution of his orders”.

These people are so much more than that donation truck, and the bell ringers we see behind the red kettles, every December.

Lieutenant Colonel William S. Barker of the Salvation Army left New York with Adjutant Bertram Rodda on June 30, 1917, to survey the situation. It wasn’t long before his not-so surprising request came back in a cable from France. Send ‘Lassies’.

A small group of carefully selected female officers was sent to France on August 22. That first party comprised six men, three women and a married couple. Within fifteen months their number had expanded by a factor of 400.

In December 1917, a plea for a million dollars went out to support the humanitarian work of the Salvation Army, the YMCA, YWCA, War Camp Community Service, National Catholic War Council, Jewish Welfare Board, the American Library Association and others. This “United War Work Campaign” raised $170 million in private donations, equivalent to $27.6 billion, today.

‘Hutments’ were formed all over the front, many right out at the front lines. There were canteen services. Religious observances of all denominations were held in these facilities. Concert performances were given, clothing mended and words of kindness offered in response to all manner of personal problems. On one occasion, the Loyal Order of Moose conducted a member initiation. Pies and cakes were baked in crude ovens and lemonade served to hot and thirsty troops.

Of all these corporal works of mercy, the ones best remembered by the ‘doughboys’ themselves, were the doughnuts.

Helen Purviance, sent to France in 1917 with the American 1st Division, seems to have been first with the idea. An ensign with the Salvation Army, Purviance and fellow ensign Margaret Sheldon first formed the dough by hand, later using a wine bottle in lieu of a rolling pin. Having no doughnut cutter at the time, dough was shaped and twisted into crullers, fried seven at a time in a lard-filled helmet, on a pot-bellied wood stove.

The work was grueling. The women worked well into the night that first day, serving all of 150 hand-made doughnuts. “I was literally on my knees,” Purviance recalled, but it was easier than bending down all day, on that tiny wood stove. It didn’t seem to matter. Men stood in line for hours, patiently waiting in the mud and the rain of that world of misery, for their own little piece of warm, home-cooked heaven.

Techniques gradually improved and it certainly helped, when these there was a real pan to cook in. These ladies were soon turning out 2,500 to 9,000 doughnuts a day. An elderly French blacksmith made Purviance a doughnut cutter, out of a condensed milk can and a camphor-ice tube, attached to a wooden block.

Before long the pleasant aroma of hot doughnuts could be detected, wafting all over the dugouts and trenches of the western front. Salvation Army volunteers and others made apple pies and all manner of other goodies, but the name that stuck, was “Doughnut Lassies”.

One New York Times correspondent wrote in 1918 “When I landed in France I didn’t think so much of the Salvation Army; after two weeks with the Americans at the front I take my hat off… [W]hen the memoirs of this war come to be written the doughnuts and apple pies of the Salvation Army are going to take their place in history”.

Contrary to popular myth the doughnut was not invented in WW1. Neither was the name for soldiers of the Great War although millions of “doughboys” returned from ‘over there’ requesting wives, mothers sweethearts and local bakeries make their newfound favorite confection. Russian émigré Adolph Levitt invented the first doughnut machine in 1920. The round cake with the hole in the middle, has never looked back.

If you’re interested, the Doughnut Lassies’ original WW1 recipe may be found, HERE. Let me know how they come out.

Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. Five French officers commanded a core group of 38 American volunteers, supported by all-French mechanics and ground crew. Rounding out the Escadrille were the unit mascots, the African lions Whiskey and Soda.

Escadrille N.124 changed its name in December 1916, adopting that of a French hero of the American Revolution. Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. Five French officers commanded a core group of 38 American volunteers, supported by all-French mechanics and ground crew. Rounding out the Escadrille were the unit mascots, the African lions Whiskey and Soda.

As chief of the Imperial German general staff from 1891-1905, German Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen devised the strategic roadmap by which Germany prosecuted the first world war. The “Schlieffen Plan” could be likened to a bar fight, where a fighter (Germany) had to take out one guy fast (France), before turning and facing his buddy (Imperial Russia). Of infinite importance to Schlieffen’s plan was the westward sweep through France, rolling the country into a ball on a timetable before his armies could turn east to face the “Russian Steamroller”. “When you march into France”, Schlieffen had said, “let the last man on the right brush the Channel with his sleeve.”

As chief of the Imperial German general staff from 1891-1905, German Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen devised the strategic roadmap by which Germany prosecuted the first world war. The “Schlieffen Plan” could be likened to a bar fight, where a fighter (Germany) had to take out one guy fast (France), before turning and facing his buddy (Imperial Russia). Of infinite importance to Schlieffen’s plan was the westward sweep through France, rolling the country into a ball on a timetable before his armies could turn east to face the “Russian Steamroller”. “When you march into France”, Schlieffen had said, “let the last man on the right brush the Channel with his sleeve.”

The second Battle of Ypres began with a new and terrifying weapon, on April 22, 1915. German troops placed 5,730 gas cylinders weighing 90 pounds apiece, along a four mile front. Allied troops must have looked on in wonder, as that vast yellow-green carpet crept toward their lines. Chlorine gas forms hypochlorous acid when combined with water, destroying the moist tissues of the lungs and eyes. Heavier than air, the stuff crept along the ground and poured into the trenches, forcing troops out into heavy German fire. 6,000 casualties were sustained in the gas attack alone, opening a four mile gap in the allied line. Thousands retched and coughed out their last breath, as others tossed their equipment and ran in terror.

The second Battle of Ypres began with a new and terrifying weapon, on April 22, 1915. German troops placed 5,730 gas cylinders weighing 90 pounds apiece, along a four mile front. Allied troops must have looked on in wonder, as that vast yellow-green carpet crept toward their lines. Chlorine gas forms hypochlorous acid when combined with water, destroying the moist tissues of the lungs and eyes. Heavier than air, the stuff crept along the ground and poured into the trenches, forcing troops out into heavy German fire. 6,000 casualties were sustained in the gas attack alone, opening a four mile gap in the allied line. Thousands retched and coughed out their last breath, as others tossed their equipment and ran in terror.

Richly typeset advertisements for “Music Hall Extravaganzas” include “Tickling Fritz” by the P.B.I. (Poor Bloody Infantry) Film Co. of the United Kingdom and Canada, advising the enthusiast to “Book Early”. There were Real Estate ads for property in no-man’s land. “BUILD THAT HOUSE ON HILL 60. BRIGHT-BREEZY-&-INVIGORATING. COMMANDS AN EXCELLENT VIEW OF HISTORIC TOWN OF YPRES”. Another one read “FOR SALE, THE SALIENT ESTATE – COMPLETE IN EVERY DETAIL! UNDERGROUND RESIDENCES READY FOR HABITATION. Splendid Motoring Estate! Shooting Perfect !! Fishing Good!!!”

Richly typeset advertisements for “Music Hall Extravaganzas” include “Tickling Fritz” by the P.B.I. (Poor Bloody Infantry) Film Co. of the United Kingdom and Canada, advising the enthusiast to “Book Early”. There were Real Estate ads for property in no-man’s land. “BUILD THAT HOUSE ON HILL 60. BRIGHT-BREEZY-&-INVIGORATING. COMMANDS AN EXCELLENT VIEW OF HISTORIC TOWN OF YPRES”. Another one read “FOR SALE, THE SALIENT ESTATE – COMPLETE IN EVERY DETAIL! UNDERGROUND RESIDENCES READY FOR HABITATION. Splendid Motoring Estate! Shooting Perfect !! Fishing Good!!!”

By the last year of WW1, the French, British and Belgians had at least 20,000 dogs on the battlefield, the Germans 30,000. General Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Forces recommended the use of dogs as sentries, messengers and draft animals in the spring of 1918. However, with the exception of a few sled dogs in Alaska, the US was the only country to take part in World War I with virtually no service dogs in its military.

By the last year of WW1, the French, British and Belgians had at least 20,000 dogs on the battlefield, the Germans 30,000. General Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Forces recommended the use of dogs as sentries, messengers and draft animals in the spring of 1918. However, with the exception of a few sled dogs in Alaska, the US was the only country to take part in World War I with virtually no service dogs in its military.

Stubby saw his first action at Chemin des Dames. Since the boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him, he learned to follow the men’s example of ducking when the big ones came close. It became a great game to see who could hit the dugout, first. After a few days, the guys were watching him for a signal. Stubby was always the first to hear incoming fire. We can only guess how many lives were spared by his early warning.

Stubby saw his first action at Chemin des Dames. Since the boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him, he learned to follow the men’s example of ducking when the big ones came close. It became a great game to see who could hit the dugout, first. After a few days, the guys were watching him for a signal. Stubby was always the first to hear incoming fire. We can only guess how many lives were spared by his early warning.

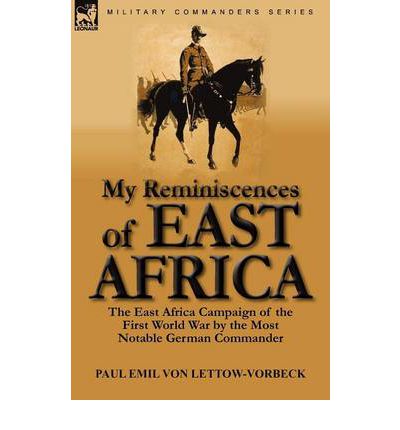

Stationed in German East Africa and knowing that his sector would be little more than a side show in the greater war effort, Lettow-Vorbeck determined to tie up as many of his adversaries as possible.

Stationed in German East Africa and knowing that his sector would be little more than a side show in the greater war effort, Lettow-Vorbeck determined to tie up as many of his adversaries as possible.

In 1964, the year Lettow-Vorbeck died, the Bundestag voted to give back pay to former African warriors who had fought with German forces in WWI. Some 350 elderly Ascaris showed up. A few could produce certificates given them back in 1918, some had scraps of old uniforms. Precious few could prove their former service to the German Empire.

In 1964, the year Lettow-Vorbeck died, the Bundestag voted to give back pay to former African warriors who had fought with German forces in WWI. Some 350 elderly Ascaris showed up. A few could produce certificates given them back in 1918, some had scraps of old uniforms. Precious few could prove their former service to the German Empire.

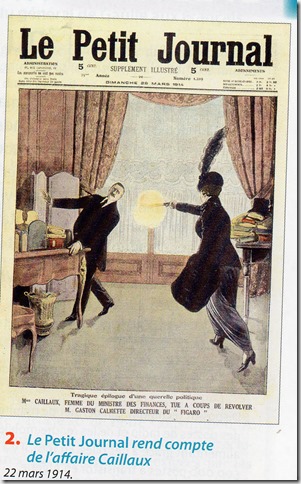

Right, the fall of the powerful, and all the salacious details anyone could ask for. Most of France was riveted by the Caillaux affair in July 1914, ignorant of the European crisis barreling down on them like the four horsemen of the apocalypse. Madame Caillaux’s trial for the murder of Gaston Calmette began on July 20.

Right, the fall of the powerful, and all the salacious details anyone could ask for. Most of France was riveted by the Caillaux affair in July 1914, ignorant of the European crisis barreling down on them like the four horsemen of the apocalypse. Madame Caillaux’s trial for the murder of Gaston Calmette began on July 20.

On the morning of March 11, 1918, most of the recruits at Fort Riley, Kansas, were turning out for breakfast. Private Albert Gitchell reported to the hospital, complaining of cold-like symptoms of sore throat, fever and headache. By noon, more than 100 more had reported sick with similar symptoms.

On the morning of March 11, 1918, most of the recruits at Fort Riley, Kansas, were turning out for breakfast. Private Albert Gitchell reported to the hospital, complaining of cold-like symptoms of sore throat, fever and headache. By noon, more than 100 more had reported sick with similar symptoms. within hours of the first symptoms. There’s a story about four young, healthy women playing bridge well into the night. By morning, three were dead of influenza.

within hours of the first symptoms. There’s a story about four young, healthy women playing bridge well into the night. By morning, three were dead of influenza. Around the planet, the Spanish flu infected 500 million people. A third of the population of the entire world, at that time. Estimates run as high 50 to 100 million killed. For purposes of comparison, the “Black Death” of 1347-51 killed 20 million Europeans.

Around the planet, the Spanish flu infected 500 million people. A third of the population of the entire world, at that time. Estimates run as high 50 to 100 million killed. For purposes of comparison, the “Black Death” of 1347-51 killed 20 million Europeans.

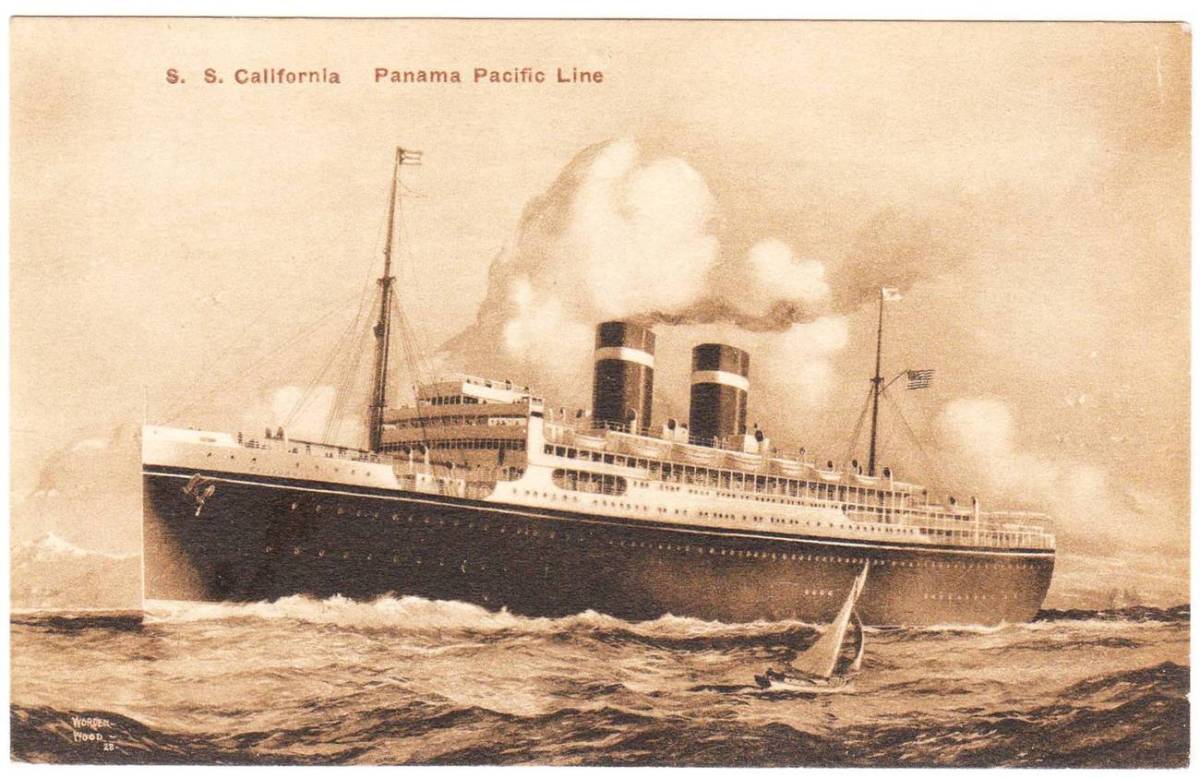

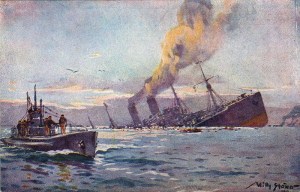

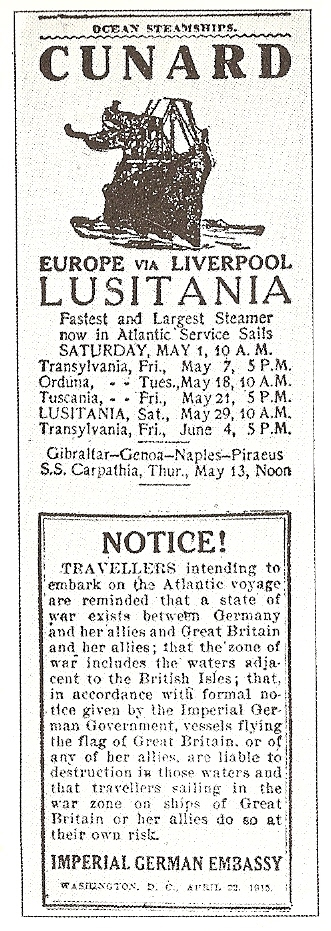

On February 4, 1915, Imperial Germany declared a naval blockade against shipping to Britain, stating that “On and after February 18th every enemy merchant vessel found in this region will be destroyed, without its always being possible to warn the crews or passengers of the dangers threatening”. “Neutral ships” it continued, “will also incur danger in the war region”.

On February 4, 1915, Imperial Germany declared a naval blockade against shipping to Britain, stating that “On and after February 18th every enemy merchant vessel found in this region will be destroyed, without its always being possible to warn the crews or passengers of the dangers threatening”. “Neutral ships” it continued, “will also incur danger in the war region”.

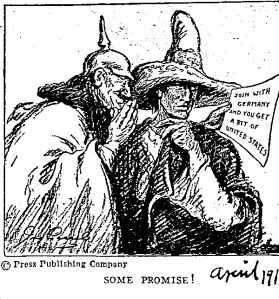

Unrestricted submarine warfare was suspended for a time, for fear of bringing the US into the war. The policy was reinstated in January 1917, prompting then-Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg to say, “Germany is finished”. He was right.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was suspended for a time, for fear of bringing the US into the war. The policy was reinstated in January 1917, prompting then-Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg to say, “Germany is finished”. He was right. secretary of the United States Embassy in Britain. This was an overture from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the Mexican government , promising American territories in exchange for a Mexican declaration of war against the US.

secretary of the United States Embassy in Britain. This was an overture from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the Mexican government , promising American territories in exchange for a Mexican declaration of war against the US.

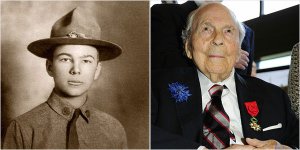

In 2003, author Richard Rubin set out to interview the last surviving veterans of World War One. The people he sought were over 101, one was 113.

In 2003, author Richard Rubin set out to interview the last surviving veterans of World War One. The people he sought were over 101, one was 113.

Frank Woodruff Buckles, born Wood Buckles, is one of them. Born on this day in 1901, Buckles joined the Ambulance Corps of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) at the age of 16. He never saw combat against the Germans, but he would escort 650 of them back home as prisoners.

Frank Woodruff Buckles, born Wood Buckles, is one of them. Born on this day in 1901, Buckles joined the Ambulance Corps of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) at the age of 16. He never saw combat against the Germans, but he would escort 650 of them back home as prisoners.

You must be logged in to post a comment.