In 1869, Germany had yet to come into its own as an independent nation. Forty-five years later, she was one of the Great Powers, of Europe.

Alarmed by the aggressive growth of her historic adversary, the French government had by that time increased compulsory military service from two years to three, in an effort to offset the advantage conferred by a German population of some 70 million, contrasted with a French population of 40 million.

Joseph Caillaux was a left wing politician, once Prime Minister of France and, by 1913, a cabinet minister under the more conservative administration of French President Raymond Poincare.

Never too discreet with his personal conduct, Caillaux paraded through public life with a succession of women, who were not Mrs Caillaux. One of them was Henriette Raynouard. By 1911, Madame Raynouard had become the second Mrs Caillaux.

A relative pacifist, many on the French right considered Caillaux to be too “soft” on Germany. One of them was Gaston Calmette, editor of the leading right-wing newspaper Le Figaro, who regularly excoriated the politician.

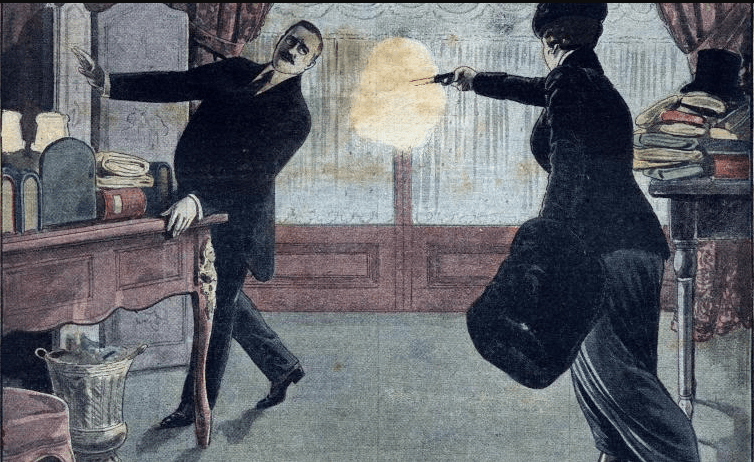

On March 16, 1914, Madame Caillaux took a taxi to the offices of Le Figaro. She waited for a full hour to see the paper’s editor, before walking into his office and shooting him at his desk. Four out of six rounds hit their mark. Gaston Calmette was dead before the night was through.

It was the crime of the century. This one had everything: Left vs. Right, the fall of the powerful, and all the salacious details anyone could ever ask for. It was the OJ trial, version 1.0, and the French public was transfixed.

The British public was similarly distracted, by the latest in a series of Irish Home Rule crises.

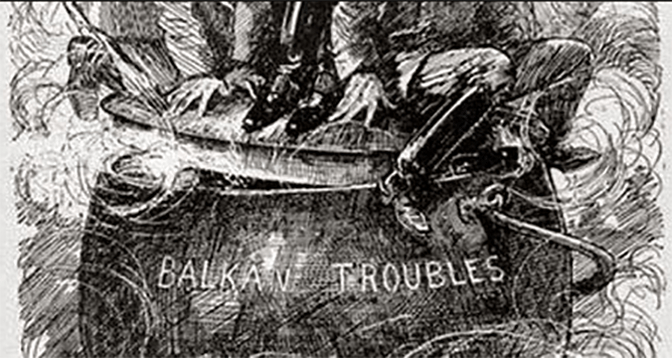

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, a sprawling amalgamation of 17 nations, 20 Parliamentary groups and 27 political parties, desperately needed to bring the Balkan peninsula into line, following the June 28 assassination of the heir apparent to the dual monarchy. That individual Serbians were complicit in the assassination is beyond doubt, but so many government records of the era have disappeared that, it’s impossible to determine official Serbian complicity. Nevertheless, Serbia had to be brought to heel.

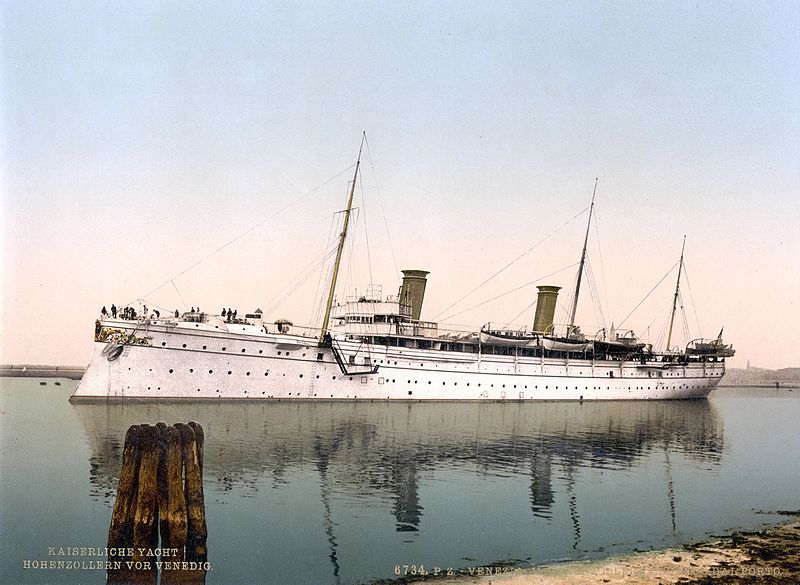

Having given Austria his personal assurance of support in the event of war with Serbia, even if Russia entered in support of her Slavic ally, Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany left on a summer cruise in the Norwegian fjords. The Kaiser’s being out of touch for those critical days in July has been called the most expensive maritime disaster in naval history.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire delivered a deliberately unacceptable ultimatum to Serbia on the 23rd, little more that a bald pretext for war. Czar Nicholas wired Vienna as late as the 27th proposing an international conference concerning Serbia, but to no avail. Austria responded that same day. It was too late for such a proposal.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on Serbia the following day, the day on which Madame Caillaux was acquitted of the murder of Gaston Calmette, on the grounds of being a “crime of passion”.

As expected, Russia mobilized in support of Serbia. For her part, Imperial Germany feared little more than a two-front war, with the “Russian Steamroller” to the east, and the French Republic to the west. Germany invaded neutral Belgium in pursuit of the one-two punch strategy by which she sought first to defeat France, before turning to face the far larger Russian adversary.

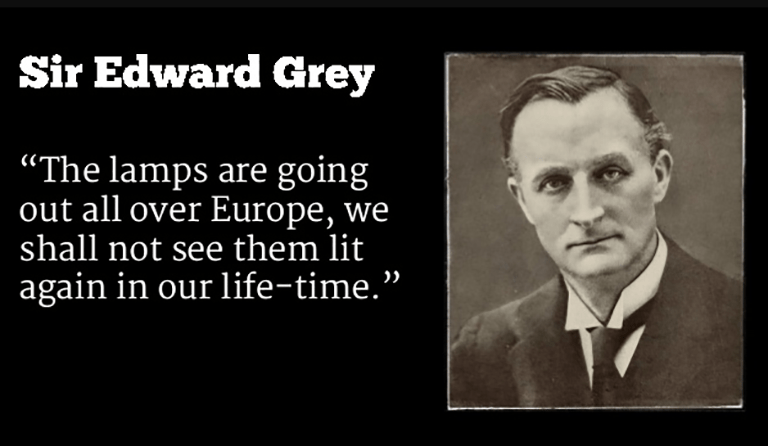

On August 3, British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey announced before Parliament, his government’s intention to defend Belgian neutrality, a treaty obligation German diplomats had dismissed as a “scrap of paper”.

Pre-planned timetables took over – France alone would have 3,781,000 military men under orders before the middle of August, arriving at the western front on 7,000 trains arriving as often as every eight minutes.

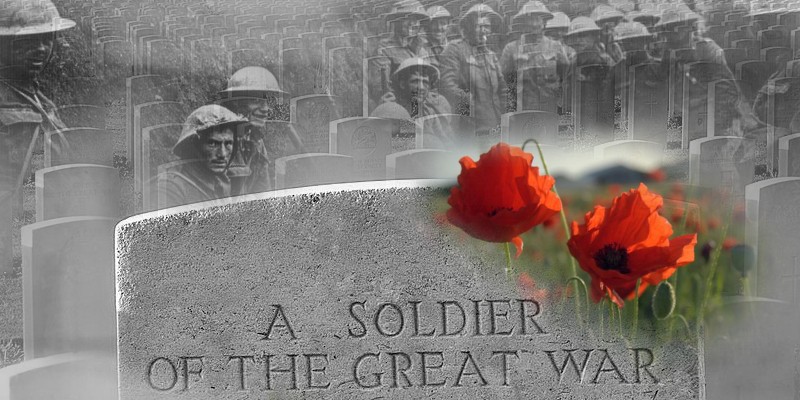

This time there would be no “Phoney War”, no “Sitzkreig”, as some wags were wont to call the early days of WWII. Few could imagine a cataclysm to rock a century and beyond, a war in which a single day’s fighting could produce casualties equal to that of every war of the preceding 100 years, combined. Fewer still understood on this date, one-hundred and four years ago, today. The four horsemen of the Apocalypse, were only days away.

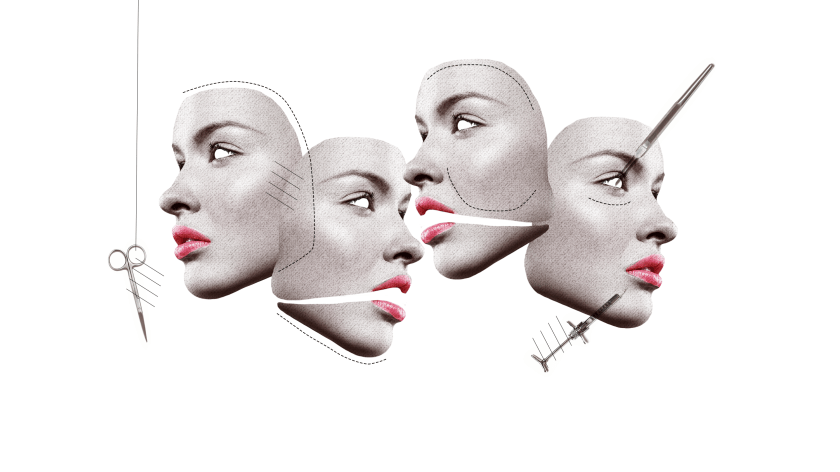

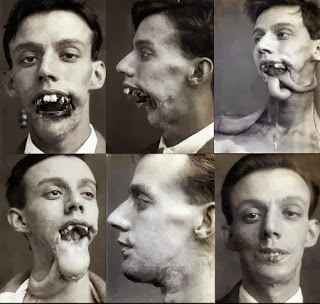

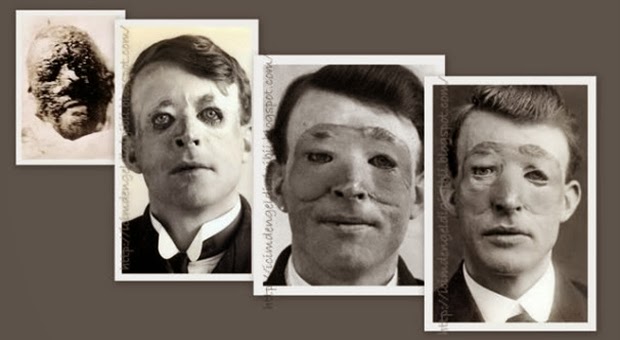

“Plastic” Surgery, the term comes to us from the Greek Plastikos and first used by the 18th century French surgeon Pierre Desault, has been with us longer than you might expect. Evidence exists of Hindu surgeons performing primitive ‘nose jobs’, as early as BC800-600. The Renaissance-era surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599) developed new methods of reconstruction, using the patient’s own arm skin to replace noses slashed off in swordplay.

“Plastic” Surgery, the term comes to us from the Greek Plastikos and first used by the 18th century French surgeon Pierre Desault, has been with us longer than you might expect. Evidence exists of Hindu surgeons performing primitive ‘nose jobs’, as early as BC800-600. The Renaissance-era surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599) developed new methods of reconstruction, using the patient’s own arm skin to replace noses slashed off in swordplay.

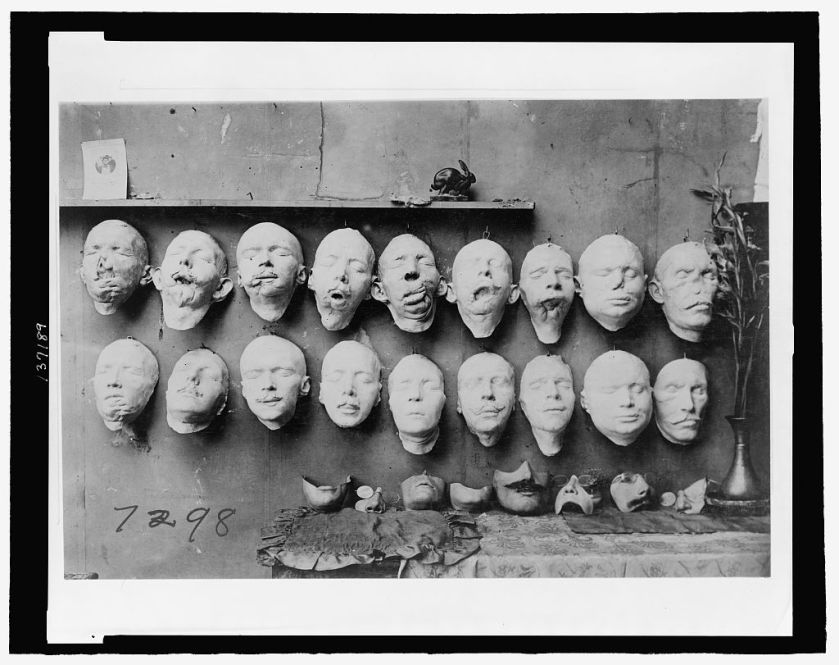

Ladd’s prostheses were uncomfortable to wear, but her services earned her the Légion d’Honneur Croix de Chevalier and the Serbian Order of Saint Sava.

Ladd’s prostheses were uncomfortable to wear, but her services earned her the Légion d’Honneur Croix de Chevalier and the Serbian Order of Saint Sava.

Dr. Gillies & Co. developed surgical methods in which rib cartilage is first implanted in foreheads, and then swung down to form the foundational structure of a new nose.

Dr. Gillies & Co. developed surgical methods in which rib cartilage is first implanted in foreheads, and then swung down to form the foundational structure of a new nose.

3,662,374 military service certificates were issued to qualifying veterans, bearing a face value equal to $1 per day of domestic service and $1.25 a day for overseas service, plus interest. Total face value of these certificates was $3.638 billion, equivalent to $43.7 billion in today’s dollars and coming to full maturity in 1945.

3,662,374 military service certificates were issued to qualifying veterans, bearing a face value equal to $1 per day of domestic service and $1.25 a day for overseas service, plus interest. Total face value of these certificates was $3.638 billion, equivalent to $43.7 billion in today’s dollars and coming to full maturity in 1945. The Great Depression was two years old in 1932, and thousands of veterans had been out of work since the beginning. Certificate holders could borrow up to 50% of the face value of their service certificates, but direct funds remained unavailable for another 13 years.

The Great Depression was two years old in 1932, and thousands of veterans had been out of work since the beginning. Certificate holders could borrow up to 50% of the face value of their service certificates, but direct funds remained unavailable for another 13 years. This had happened before. Hundreds of Pennsylvania veterans of the Revolution had marched on Washington in 1783, after the Continental Army was disbanded without pay.

This had happened before. Hundreds of Pennsylvania veterans of the Revolution had marched on Washington in 1783, after the Continental Army was disbanded without pay.

Marchers and their families were in their camps on July 28 when Attorney General William Mitchell ordered them evicted. Two policemen became trapped on the second floor of a building when they drew their revolvers and shot two veterans, William Hushka and Eric Carlson, both of whom died of their injuries.

Marchers and their families were in their camps on July 28 when Attorney General William Mitchell ordered them evicted. Two policemen became trapped on the second floor of a building when they drew their revolvers and shot two veterans, William Hushka and Eric Carlson, both of whom died of their injuries. President Herbert Hoover ordered the Army under General Douglas MacArthur to evict the Bonus Army from Washington. 500 Cavalry formed up on Pennsylvania Avenue at 4:45pm, supported by 500 Infantry, 800 police and six battle tanks under the command of then-Major George S. Patton. Civil Service employees came out to watch as bonus marchers cheered, thinking that the Army had gathered in their support.

President Herbert Hoover ordered the Army under General Douglas MacArthur to evict the Bonus Army from Washington. 500 Cavalry formed up on Pennsylvania Avenue at 4:45pm, supported by 500 Infantry, 800 police and six battle tanks under the command of then-Major George S. Patton. Civil Service employees came out to watch as bonus marchers cheered, thinking that the Army had gathered in their support. Bonus marchers fled to their largest encampment across the Anacostia River, when President Hoover ordered the assault stopped. Feeling that the Bonus March was an attempt to overthrow the government, General MacArthur ignored the President and ordered a new attack, the army routing 10,000 and leaving their camps in flames. 1,017 were injured and 135 arrested.

Bonus marchers fled to their largest encampment across the Anacostia River, when President Hoover ordered the assault stopped. Feeling that the Bonus March was an attempt to overthrow the government, General MacArthur ignored the President and ordered a new attack, the army routing 10,000 and leaving their camps in flames. 1,017 were injured and 135 arrested. Then-Major Dwight D. Eisenhower was one of MacArthur’s aides at the time. Eisenhower believed that it was wrong for the Army’s highest ranking officer to lead an action against fellow war veterans. “I told that dumb son-of-a-bitch not to go down there”, he said.

Then-Major Dwight D. Eisenhower was one of MacArthur’s aides at the time. Eisenhower believed that it was wrong for the Army’s highest ranking officer to lead an action against fellow war veterans. “I told that dumb son-of-a-bitch not to go down there”, he said. The bonus march debacle doomed any chance that Hoover had of being re-elected. Franklin D. Roosevelt opposed the veterans’ bonus demands during the election, but was able to negotiate a solution when veterans organized a second demonstration in 1933. Roosevelt’s wife Eleanor was instrumental in these negotiations, leading one veteran to quip: “Hoover sent the army. Roosevelt sent his wife”.

The bonus march debacle doomed any chance that Hoover had of being re-elected. Franklin D. Roosevelt opposed the veterans’ bonus demands during the election, but was able to negotiate a solution when veterans organized a second demonstration in 1933. Roosevelt’s wife Eleanor was instrumental in these negotiations, leading one veteran to quip: “Hoover sent the army. Roosevelt sent his wife”.

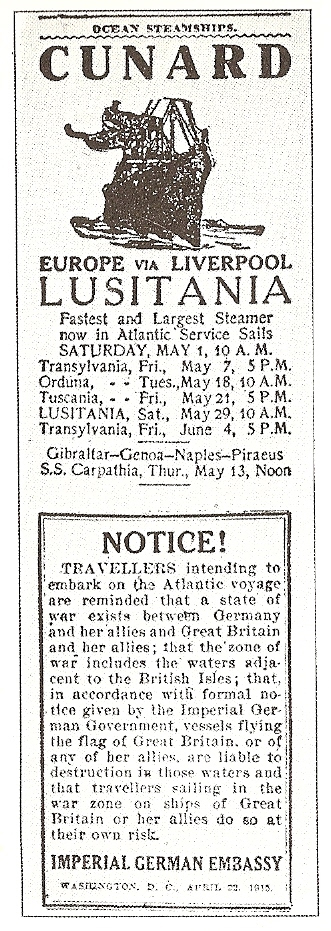

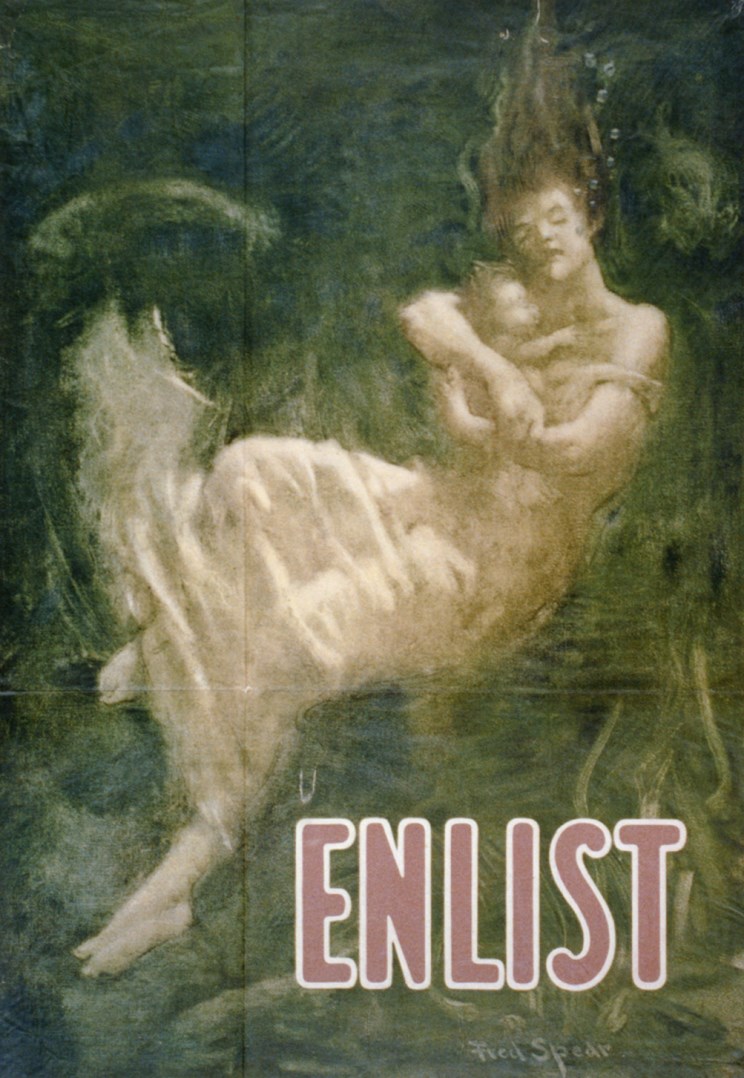

Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare on February 18, 1915. The German embassy took out ads in American newspapers, warning that ships sailing into the war zone, did so at their own risk. That didn’t seem to bother anyone as they boarded RMS Lusitania.

Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare on February 18, 1915. The German embassy took out ads in American newspapers, warning that ships sailing into the war zone, did so at their own risk. That didn’t seem to bother anyone as they boarded RMS Lusitania.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed the same month. In February a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California off the Irish coast, killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew. President Wilson asked for a declaration of war in a speech to a joint session of Congress on April 2. From the text of the speech, it seems the Germans were right. It was the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare which provoked the United States to enter the war against Germany, which it did when Congress declared war on April 6.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed the same month. In February a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California off the Irish coast, killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew. President Wilson asked for a declaration of war in a speech to a joint session of Congress on April 2. From the text of the speech, it seems the Germans were right. It was the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare which provoked the United States to enter the war against Germany, which it did when Congress declared war on April 6.

Field Marshall Helmuth von Moltke once said “No battle plan ever survives contact with the enemy”. So it was in the tiny Belgian city where German plans met with ruin, on the road to Dunkirk. Native Dutch speakers called the place Leper. Today we know it as Ypres (Ee-pres), since battle maps of the time were drawn up in French. To the Tommys of the British Expeditionary Force, the place was “Wipers”.

Field Marshall Helmuth von Moltke once said “No battle plan ever survives contact with the enemy”. So it was in the tiny Belgian city where German plans met with ruin, on the road to Dunkirk. Native Dutch speakers called the place Leper. Today we know it as Ypres (Ee-pres), since battle maps of the time were drawn up in French. To the Tommys of the British Expeditionary Force, the place was “Wipers”. The second Battle for Ypres began with a new and terrifying weapon on April 22, 1915. German troops placed 5,730 gas cylinders weighing 90 pounds apiece, along a four-mile front. Allied troops must have looked on in wonder, as that vast yellow-green carpet crept toward their lines.

The second Battle for Ypres began with a new and terrifying weapon on April 22, 1915. German troops placed 5,730 gas cylinders weighing 90 pounds apiece, along a four-mile front. Allied troops must have looked on in wonder, as that vast yellow-green carpet crept toward their lines.

Units of all sizes, from individual companies to army corps, lightened the load of the “War to end all Wars”, with some kind of unit journal.

Units of all sizes, from individual companies to army corps, lightened the load of the “War to end all Wars”, with some kind of unit journal.

America’s first war dog, “Stubby”, got there by accident, and served 18 months ‘over there’, participating in seventeen battles on the Western Front.

America’s first war dog, “Stubby”, got there by accident, and served 18 months ‘over there’, participating in seventeen battles on the Western Front. Stubby saw his first action at Chemin des Dames. Since the boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him, he learned to follow the example of ducking when the big ones came close. It became a great game to see who could hit the dugout, first. After a few days, the guys were watching him for a signal. Stubby was always the first to hear incoming fire. We can only guess how many lives were spared by his early warning.

Stubby saw his first action at Chemin des Dames. Since the boom of artillery fire didn’t faze him, he learned to follow the example of ducking when the big ones came close. It became a great game to see who could hit the dugout, first. After a few days, the guys were watching him for a signal. Stubby was always the first to hear incoming fire. We can only guess how many lives were spared by his early warning. After the Armistice, Stubby returned home a nationally acclaimed hero, eventually received by both Presidents Harding and Coolidge. Even General John “Black Jack” Pershing, who commanded the AEF during the war, presented Stubby with a gold medal made by the Humane Society, declaring him to be a “hero of the highest caliber.”

After the Armistice, Stubby returned home a nationally acclaimed hero, eventually received by both Presidents Harding and Coolidge. Even General John “Black Jack” Pershing, who commanded the AEF during the war, presented Stubby with a gold medal made by the Humane Society, declaring him to be a “hero of the highest caliber.”

The coming cataclysm would lay waste to a generation, and to a continent.

The coming cataclysm would lay waste to a generation, and to a continent.

On November 11, Armistice Day, the casket was removed from the Rotunda of the Capitol and escorted under military guard to the amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery. In a simple ceremony, President Warren G. Harding bestowed on this unknown soldier the Medal of Honor, and the Distinguished Service Cross.

On November 11, Armistice Day, the casket was removed from the Rotunda of the Capitol and escorted under military guard to the amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery. In a simple ceremony, President Warren G. Harding bestowed on this unknown soldier the Medal of Honor, and the Distinguished Service Cross.

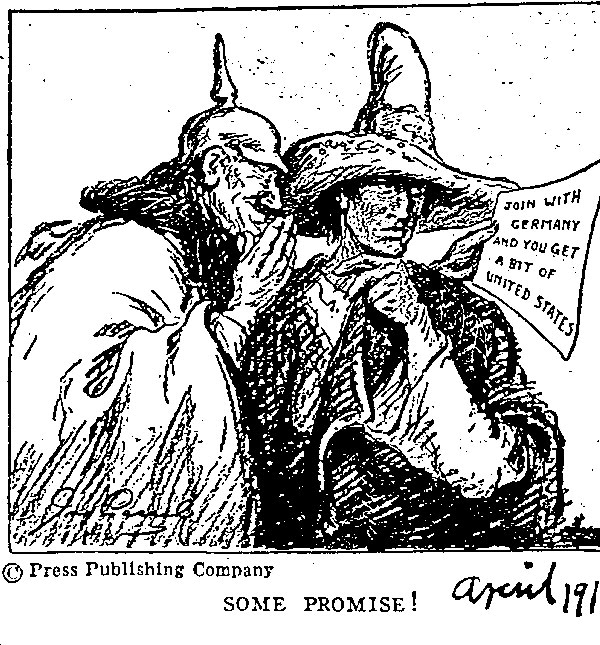

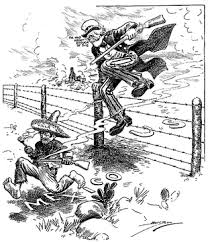

In early March, a force of some 1,500 Villistas were camped along the border three miles south of Columbus New Mexico, when Villa sent spies into Camp Columbus (later renamed Camp Furlong). Informed that Camp Columbus’ fighting strength numbered only thirty or so, a force of some 600 crossed the border around midnight on March 8.

In early March, a force of some 1,500 Villistas were camped along the border three miles south of Columbus New Mexico, when Villa sent spies into Camp Columbus (later renamed Camp Furlong). Informed that Camp Columbus’ fighting strength numbered only thirty or so, a force of some 600 crossed the border around midnight on March 8. The United States government wasted no time in responding. That same day, the President who would win re-election in eight months on the slogan “He kept us out of war” appointed Newton Diehl Baker, Jr. to fill the previously vacant position of Secretary of War. The following day, Woodrow Wilson ordered General John Pershing to capture Pancho Villa, dead or alive.

The United States government wasted no time in responding. That same day, the President who would win re-election in eight months on the slogan “He kept us out of war” appointed Newton Diehl Baker, Jr. to fill the previously vacant position of Secretary of War. The following day, Woodrow Wilson ordered General John Pershing to capture Pancho Villa, dead or alive. The 1st Aero Squadron arrived in New Mexico on March 15, with 8 aircraft, 11 pilots and 82 enlisted men. The first reconnaissance sortie was flown the following day, the first time that American aircraft were used in actual military operations.

The 1st Aero Squadron arrived in New Mexico on March 15, with 8 aircraft, 11 pilots and 82 enlisted men. The first reconnaissance sortie was flown the following day, the first time that American aircraft were used in actual military operations. On May 14, a young 2nd Lieutenant in charge of a force of fifteen and three Dodge touring cars got into a running gunfight, while foraging for corn, in Chihuahua. It was the first motorized action in American military history. Three Villistas were killed and strapped to the hoods of the cars and driven back to General Pershing’s headquarters. General Pershing nicknamed that 2nd Lt. “The Bandito”. History remembers his name as George S. Patton.

On May 14, a young 2nd Lieutenant in charge of a force of fifteen and three Dodge touring cars got into a running gunfight, while foraging for corn, in Chihuahua. It was the first motorized action in American military history. Three Villistas were killed and strapped to the hoods of the cars and driven back to General Pershing’s headquarters. General Pershing nicknamed that 2nd Lt. “The Bandito”. History remembers his name as George S. Patton.

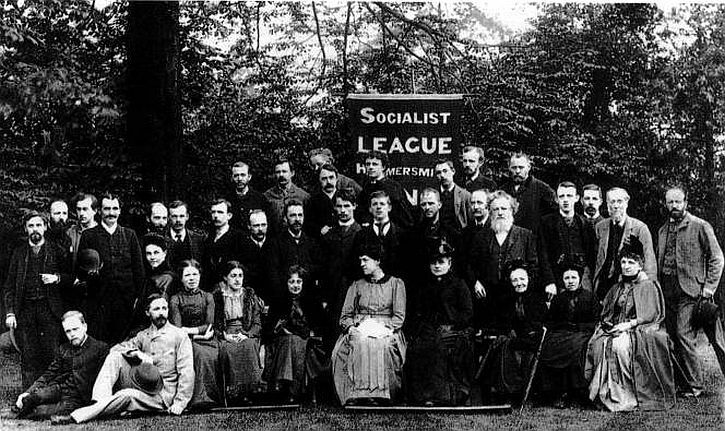

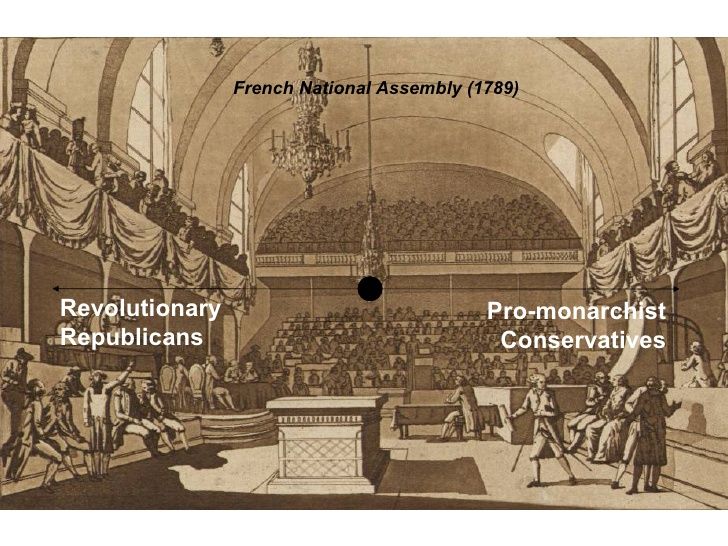

By that time it wasn’t just the “Party of Order” on the right and the “Party of Movement” on the left. Now, the terms began to describe nuances in political philosophy, as well.

By that time it wasn’t just the “Party of Order” on the right and the “Party of Movement” on the left. Now, the terms began to describe nuances in political philosophy, as well.

The July Crisis of 1914 was a series of diplomatic maneuverings, culminating in the ultimatum from Austria-Hungary to the Kingdom of Serbia. Vienna, with tacit support from Berlin, made plans to punish Serbia for her role in the assassination, while Russia mobilized armies in support of her Slavic ally.

The July Crisis of 1914 was a series of diplomatic maneuverings, culminating in the ultimatum from Austria-Hungary to the Kingdom of Serbia. Vienna, with tacit support from Berlin, made plans to punish Serbia for her role in the assassination, while Russia mobilized armies in support of her Slavic ally.

In the days that followed, the Czar would begin the mobilization of men and machines which would place Imperial Russia on a war footing. Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany invaded Belgium, in pursuit of the one-two punch strategy by which it sought first to defeat France, before turning to face the “Russian Steamroller”. England declared war in support of a 75-year-old commitment to protect Belgian neutrality, a treaty obligation German diplomats had dismissed as a “

In the days that followed, the Czar would begin the mobilization of men and machines which would place Imperial Russia on a war footing. Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany invaded Belgium, in pursuit of the one-two punch strategy by which it sought first to defeat France, before turning to face the “Russian Steamroller”. England declared war in support of a 75-year-old commitment to protect Belgian neutrality, a treaty obligation German diplomats had dismissed as a “

You must be logged in to post a comment.