In 2003, author Richard Rubin set out to interview the last surviving veterans of the Great War, the “War to End All Wars”. World War One.

The people the author sought were all over 101. One was 113. It could not have been easy, beginning with the phone call to next of kin. There is no delicate way to ask the question. “Is he still with us?” Most times the answer was “no”.

Sometimes it was “yes”, and Rubin would ask for an interview. The memories his subjects sought to bring back were 80 years old and more. Some spoke haltingly, and with difficulty. Others were fountains of information, as clear and lucid as if the memories of which they spoke were made only yesterday.

Rubin writes “Quite a few of them told me that they were telling me things that they hadn’t talked about in 50, 60, 70 years. I asked a few of them why not, and the surprising response often was that nobody had asked.”

Anthony Pierro of Swampscott, Massachusetts, served in Battery E of the 320th Field Artillery and fought in several of the major battles of 1918, including Oise-Aisne, St. Mihiel, and Meuse-Argonne.

Pierro recalled his time in Bordeaux as the best time of the war. “The girls used to say, ‘upstairs, two dollars.’” Pierro’s nephew Rick interrupted the interview. “But you didn’t go upstairs.” Although possibly unexpected, Uncle Anthony’s response was a classic. “I didn’t have the two dollars”.

Reuben Law of Carson City, Nevada remembered a troop convoy broken up by a German U-Boat while his own transport was swept up in the murderous Flu pandemic of 1918.

The people Rubin spoke with weren’t all men. 107-year-old Hildegarde Schan of Plymouth, Massachusetts spoke of caring for the wounded.

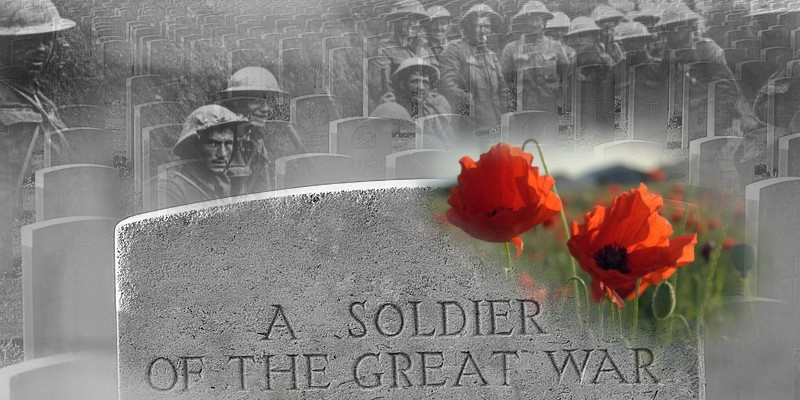

Howard Ramsey helped start an American burial ground in France, 150 miles north of Paris. Today, the 130½ acres of the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery serves as the final resting place for the largest number of US military dead in Europe.

“So I remember one night”, Ramsey said, “It was cold, and we had no blankets, or nothing like that. We had to sleep, we slept in the cemetery, because we could sleep between the two graves, and keep the wind off of us, see?”

Arthur Fiala of Kewaunee, Wisconsin remembered traveling across France in a boxcar marked “40-8″. Room enough for 40 men, or eight horses.

There was J. Laurence Moffitt of Orleans, Massachusetts. Today, we see the “Yankee Division” only on highway signs. At 106, this man was the last surviving member of his outfit, with a memory so clear he could recall every number from every fighting unit of the 26th Division.

George Briant was caught in an open field with his battery, as German planes dropped bombs from the sky. Briant felt as if he was hit by every one of them, spending several months in the hospital. When it was through, he begged to go back to the front.

On the last night of the war, November 10, 1918, Briant came upon the bodies of several men who had just been shelled.

“Such fine, handsome, healthy young men”, he said, “to be killed on the last night of the war. I cried for their parents. I mean it’s a terrible, terrible thing to lose anyone you love in a war, but imagine knowing precisely when that war ends, and then knowing that your loved one died just hours before that moment.”

Rubin interviewed dozens of men and a handful of women, a tiny and ever diminishing living repository for memory of the War to End All Wars. Their stories are told in their own words and linked HERE, if you care to learn more. I highly recommend it. The words of these women and men are far more powerful than anything I can offer.

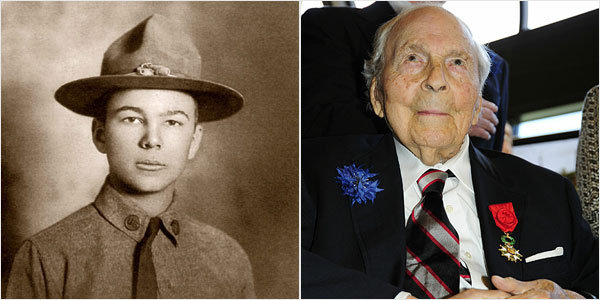

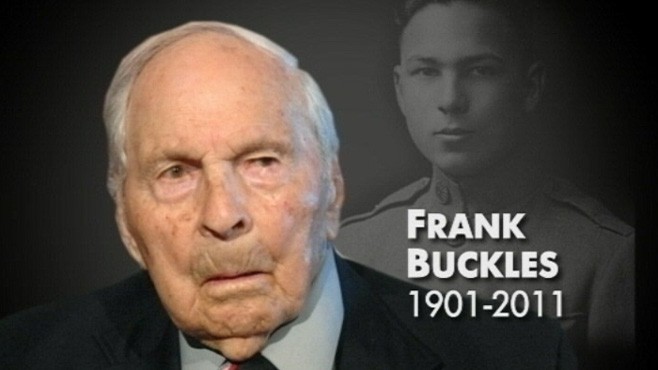

Frank Woodruff Buckles, born Wood Buckles, is one. Born on February 1, 1901, Buckles enlisted with the First Fort Riley Casualty Detachment at the age of sixteen, training for trench casualty retrieval and ambulance operations.

Buckles’ unit set sail from Hoboken New jersey in December 1917 aboard HMS Carpathia, a vessel made famous by the Titanic rescue, five years earlier.

Frank never saw combat but he did see a lot of Germans, with a Prisoner-of War escort company. Returning home in January 1920 aboard USS Pocahontas, Buckles was paid $143.90, including a $60 bonus.

Buckles was a civilian in 1940, working for the White Star Lines and WR Grace shipping companies. His work took him to the Philippines, where he remained after the outbreak of WWII. He was helping to resupply U.S. troops when captured by Japanese forces in January 1942, imprisoned for thirty-nine months as a civilian prisoner in the Santo Tomas and Los Baños prison camps.

He was rescued by the 11th Airborne Division on February 23, 1945. The day he was scheduled to be executed.

Buckles married Audrey Mayo of Pleasanton, California in 1946, and returned from whence he had come. Back to the land, back to the Gap View Farm near Charles Town, West Virginia in January 1954, to farm the land his ancestors worked back in 1732.

Audrey Mayo Buckles lived to ninety-eight and passed away on June 7, 1999. Frank continued to work the farm until 106, and still drove his tractor. For the last four years of his life he lived with his daughter Susannah near Charles Town, West Virginia.

Once asked his secret to a long life, Buckles responded, “When you start to die, don’t”.

On December 3, 2009, Frank Buckles became the oldest person ever to testify before the United States Congress, where he campaigned for a memorial to honor the 4.7 million Americans who served in World War 1.

“We still do not have a national memorial in Washington, D.C. to honor the Americans who sacrificed with their lives during World War I. On this eve of Veterans Day, I call upon the American people and the world to help me in asking our elected officials to pass the law for a memorial to World War I in our nation’s capital. These are difficult times, and we are not asking for anything elaborate. What is fitting and right is a memorial that can take its place among those commemorating the other great conflicts of the past century. On this 92nd anniversary of the armistice, it is time to move forward with honor, gratitude, and resolve”.

The United States came late to the Great War, not fully trained, equipped or mobilized until well into the last year. Even so, fully 204,000 Americans were wounded in those last few months. 116,516 never came home from a war in which, for all intents and purposes, the US fought for a bare five months.

Frank Woodruff Buckles passed away on February 27, 2011 at the age of 110, and went to his rest in Arlington National Cemetery. The last of the Doughboys, the only remaining American veteran of WWI, the last living memory of the war to end all wars, was gone.

The United States House of Representatives and Senate proposed concurrent resolutions for Buckles to lie in state, in the Capitol rotunda. For reasons still unclear, the plan was blocked by Speaker John Boehner and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. Neither Boehner nor Reid would elaborate, proposing instead a ceremony in the Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery. The President of the United States personally attended the funeral.

Washington Post reporter Reporter Paul Duggan described the occasion:

“The hallowed ritual at grave No. 34-581 was not a farewell to one man alone. A reverent crowd of the powerful and the ordinary—President Obama and Vice President Biden, laborers and store clerks, heads bowed—came to salute Buckles’s deceased generation, the vanished millions of soldiers and sailors he came to symbolize in the end”.

Frank Woodruff Buckles, the last living American veteran of WW1 was survived by the British Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF) servicewoman Florence Beatrice (Patterson) Green who died on February 4, 2012, at the age of 110.

Afterward

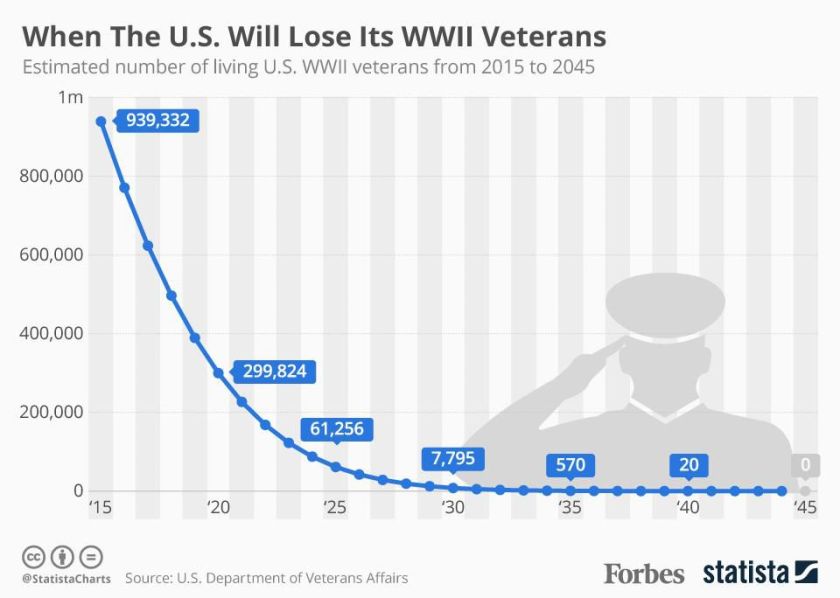

Sixteen million Americans joined with allies the world over to defeat the Axis Powers of World War 2. They were the children of Frank Buckles’ and Florence Green’s generation, sent to complete what their parents had begun. According to the Department of Veterans Affairs some 66,000 remained alive in 2024.

If actuarial projections are any indication, the Frank Buckles of his generation, the last living veteran of WW2, can be expected to pass from among us sometime around 2044.

That such an event should pass from living memory is a loss beyond measure.

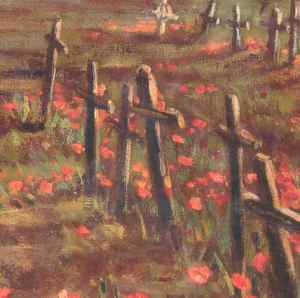

McCrae fought in one of the most horrendous battles of WWI, the second battle of Ypres, in the Flanders region of Belgium. Imperial Germany launched one of the first chemical attacks in history, attacking the Canadian position with chlorine gas on April 22, 1915. The Canadian line was broken but quickly reformed, in near-constant fighting that lasted for over two weeks.

McCrae fought in one of the most horrendous battles of WWI, the second battle of Ypres, in the Flanders region of Belgium. Imperial Germany launched one of the first chemical attacks in history, attacking the Canadian position with chlorine gas on April 22, 1915. The Canadian line was broken but quickly reformed, in near-constant fighting that lasted for over two weeks.

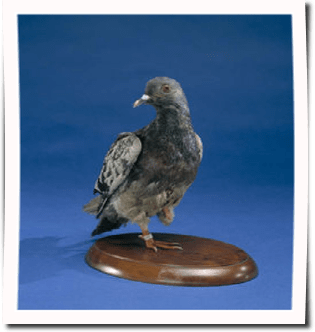

The vivid red flower blooming on the battlefields of Belgium, France and Gallipoli came to symbolize the staggering loss of life in that war. Since then, the red poppy has become an internationally recognized symbol of remembrance of the lives lost in all wars. I keep a red poppy pinned to my briefcase and another on the visor of my car. A reminder that no free citizen of a self-governing Republic, should ever forget where we come from. Or the prices paid by our forebears, to get us here.

The vivid red flower blooming on the battlefields of Belgium, France and Gallipoli came to symbolize the staggering loss of life in that war. Since then, the red poppy has become an internationally recognized symbol of remembrance of the lives lost in all wars. I keep a red poppy pinned to my briefcase and another on the visor of my car. A reminder that no free citizen of a self-governing Republic, should ever forget where we come from. Or the prices paid by our forebears, to get us here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.