Since the earliest days of the Republic, those supporting strong federal government found themselves opposed by those favoring greater self-determination by the states. In the southern regions, climate conditions led to dependence on agriculture, the rural economies of the south producing cotton, rice, sugar, indigo and tobacco. Colder states to the north tended to develop manufacturing economies, urban centers growing up in service to hubs of transportation and the production of manufactured goods.

In the first half of the 19th century, 90% of federal government revenue came from tariffs on foreign manufactured goods. A lion’s share of this revenue was collected in the south, with the region’s greater dependence on imported goods. Much of this federal largesse was spent in the north, with the construction of railroads, canals and other infrastructure.

In the first half of the 19th century, 90% of federal government revenue came from tariffs on foreign manufactured goods. A lion’s share of this revenue was collected in the south, with the region’s greater dependence on imported goods. Much of this federal largesse was spent in the north, with the construction of railroads, canals and other infrastructure.

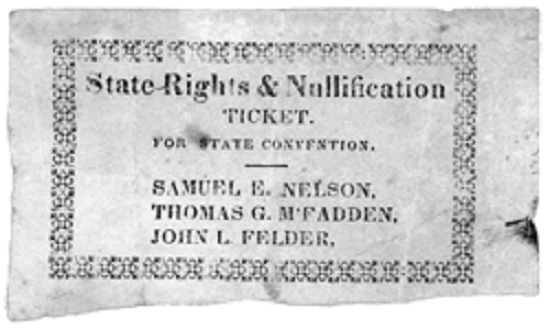

The debate over economic issues and rights of self-determination, so-called ‘state’s rights’, grew and sharpened with the “nullification crisis” of 1832-33, when South Carolina declared such tariffs to be unconstitutional and therefore null and void within the state. A cartoon from the time depicted “Northern domestic manufacturers getting fat at the expense of impoverishing the South under protective tariffs.”

Chattel slavery pre-existed the earliest days of the colonial era, from Canada to Brazil and around the world. Moral objections to what was really a repugnant institution could be found throughout, but economic forces had as much to do with ending the practice, as any other. The “peculiar institution” died out first in the colder regions of the US and may have done so in warmer climes as well, but for Eli Whitney’s invention of a cotton engine (‘gin’) in 1794.

It takes ten man-hours to remove the seeds to produce a single pound of cotton. By comparison, a cotton gin can process about a thousand pounds a day, at comparatively little expense.

The year of Whitney’s invention, the South exported 138,000 pounds a year to Europe and the northern states. Sixty years later, Great Britain alone was importing 600 million pounds a year from the southern states. Cotton was King, and with good reason. The stuff is easily grown, highly transportable, and can be stored indefinitely, compared with food crops. The southern economy turned overwhelmingly to the one crop, and its need for plentiful, cheap labor.

The issue of slavery had joined and become so intertwined with ideas of self-determination, as to be indistinguishable.

The issue of slavery had joined and become so intertwined with ideas of self-determination, as to be indistinguishable.

The first half of the 19th century was one of westward expansion, generating frequent and sharp conflicts between pro and anti-slavery factions. The Missouri compromise of 1820 attempted to reconcile the sides, defining which territories would legalize slavery, and which would be “free”.

The short-lived “Wilmot Proviso” of 1846 sought to ban slavery in new territories, after which the Compromise of 1850 attempted to strike a balance. The Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854 created two new territories, essentially repealing the Missouri Compromise and allowing settlers to determine their own direction.

This attempt to democratize the issue had the effect of drawing up battle lines. Pro-slavery forces established a territorial capital in Lecompton, while “antis” set up an alternative government in Topeka.

In Washington, Republicans backed the anti-slavery side, while most Democrats supported their opponents. On May 20, 1856, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner took to the floor of the Senate and denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Never known for verbal restraint, Sumner attacked the measure’s sponsors Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois (he of the later Lincoln-Douglas debates), and Andrew Butler of South Carolina by name, accusing the pair of “consorting with the harlot, slavery”. Douglas was in the audience at the time and quipped “this damn fool Sumner is going to get himself shot by some other damn fool”.

In Washington, Republicans backed the anti-slavery side, while most Democrats supported their opponents. On May 20, 1856, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner took to the floor of the Senate and denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Never known for verbal restraint, Sumner attacked the measure’s sponsors Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois (he of the later Lincoln-Douglas debates), and Andrew Butler of South Carolina by name, accusing the pair of “consorting with the harlot, slavery”. Douglas was in the audience at the time and quipped “this damn fool Sumner is going to get himself shot by some other damn fool”.

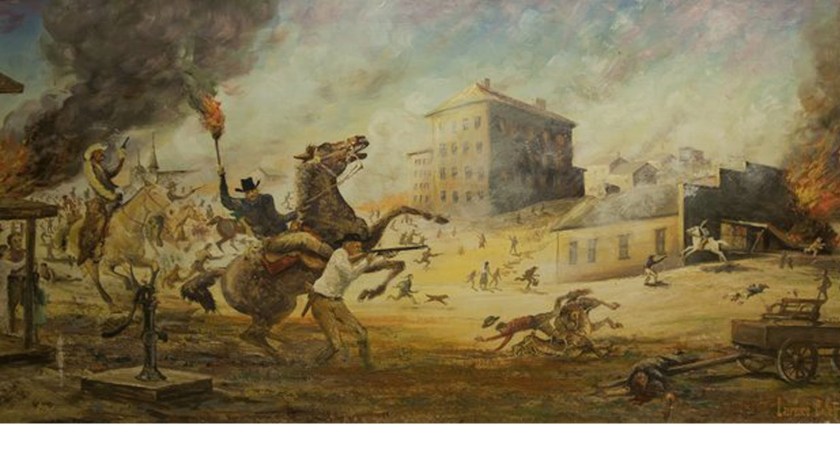

In the territories, the standoff had long since escalated to violence. Upwards of a hundred or more were killed between 1854 – 1861, in a period known as “Bleeding Kansas”.

The town of Lawrence was established by anti-slavery settlers in 1854, and soon became the focal point of pro-slavery violence. Emotions were at a boiling point when Douglas County Sheriff Samuel Jones was shot trying to arrest free-state settlers on April 23, 1856. Jones was driven out of town but he would return.

The day after Sumner’s speech, a posse of 800 pro-slavery forces converged on Lawrence Kansas, led by Sheriff Jones. The town was surrounded to prevent escape and much of it burned to the ground. This time there was only one fatality; a slavery proponent who was killed by falling masonry. Seven years later, Confederate guerrilla Robert Clarke Quantrill carried out the second sack of Lawrence. This time, most of the men and boys of the town were murdered where they stood, with little chance to defend themselves.

Meanwhile, Preston Brooks, Senator Butler’s nephew and a Member of Congress from South Carolina, had read over Sumner’s speech of the day before. Brooks was an inflexible proponent of slavery and took mortal insult from Sumner’s words.

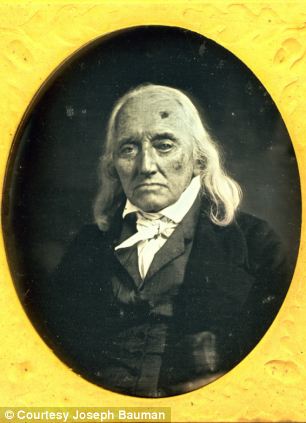

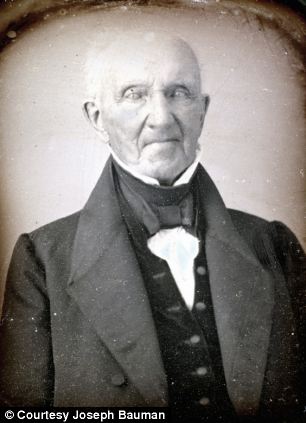

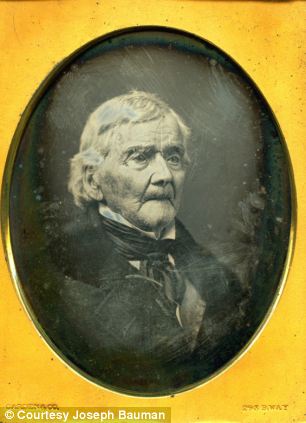

Preston Brooks (left), Charles Sumner, (right)

Brooks was furious and wanted to challenge the Senator to a duel. He discussed it with fellow South Carolina Representative Laurence Keitt, who explained that dueling was for gentlemen of equal social standing. Sumner was no gentleman, he said. No better than a drunkard.

Brooks had been shot in a duel years before, and walked with a heavy cane. Resolved to publicly thrash the Senator from Massachusetts, the Congressman entered the Senate building on May 22, in the company of Congressman Keitt and Virginia Representative Henry A. Edmundson.

The trio approached Sumner, who was sitting at his desk writing letters. “Mr. Sumner”, Brooks said, “I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.”

The trio approached Sumner, who was sitting at his desk writing letters. “Mr. Sumner”, Brooks said, “I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine.”

Sumner’s desk was bolted to the floor. He never had a chance. The Senator began to rise when Brooks brought the cane down on his head. Over and over the cane crashed down, while Keitt brandished a pistol, warning onlookers to “let them be”. Blinded by his own blood, Sumner tore the desk from the floor in his struggle to escape, losing consciousness as he tried to crawl away. Brooks rained down blows the entire time, even after the body lay motionless, until finally, the cane broke apart.

In the next two days, a group of unarmed men will be hacked to pieces by anti-slavery radicals, on the banks of Pottawatomie Creek.

In the next two days, a group of unarmed men will be hacked to pieces by anti-slavery radicals, on the banks of Pottawatomie Creek.

The 80-year-old nation forged inexorably onward, to a Civil War which would kill more Americans than every war from the American Revolution to the War on Terror, combined.

“…Venturing still farther under the buried hulk, he held tenaciously to his purpose, reaching a place immediately above the other man just as another cave-in occurred and a heavy piece of steel pinned him crosswise over his shipmate in a position which protected the man beneath from further injury while placing the full brunt of terrific pressure on himself. Although he succumbed in agony 18 hours after he had gone to the aid of his fellow divers, Hammerberg, by his cool judgment, unfaltering professional skill and consistent disregard of all personal danger in the face of tremendous odds, had contributed effectively to the saving of his 2 comrades…”.

“…Venturing still farther under the buried hulk, he held tenaciously to his purpose, reaching a place immediately above the other man just as another cave-in occurred and a heavy piece of steel pinned him crosswise over his shipmate in a position which protected the man beneath from further injury while placing the full brunt of terrific pressure on himself. Although he succumbed in agony 18 hours after he had gone to the aid of his fellow divers, Hammerberg, by his cool judgment, unfaltering professional skill and consistent disregard of all personal danger in the face of tremendous odds, had contributed effectively to the saving of his 2 comrades…”.

Carlos Norman Hathcock, born this day in Little Rock in 1942, was a Marine Corps Gunnery Sergeant and sniper with a record of 93 confirmed and greater than 300 unconfirmed kills during the American war in Vietnam.

Carlos Norman Hathcock, born this day in Little Rock in 1942, was a Marine Corps Gunnery Sergeant and sniper with a record of 93 confirmed and greater than 300 unconfirmed kills during the American war in Vietnam. The sniper’s choice of target could at times be intensely personal. One female Vietcong sniper, the platoon leader and interrogator called ‘Apache’ due to her interrogation techniques, would torture Marines and ARVN soldiers until they bled to death. Her signature was to cut the eyelids off her victims. After she skinned one Marine alive and left him emasculated within earshot of his base, Hatchcock spent weeks hunting this one sniper.

The sniper’s choice of target could at times be intensely personal. One female Vietcong sniper, the platoon leader and interrogator called ‘Apache’ due to her interrogation techniques, would torture Marines and ARVN soldiers until they bled to death. Her signature was to cut the eyelids off her victims. After she skinned one Marine alive and left him emasculated within earshot of his base, Hatchcock spent weeks hunting this one sniper.

There was no future for them in this place. Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. The family emigrated to Israel in May 1949, resuming their musical tour and performing until the group retired in 1955.

There was no future for them in this place. Only 50 of the 650 Jewish inhabitants of the village ever returned. The family emigrated to Israel in May 1949, resuming their musical tour and performing until the group retired in 1955.

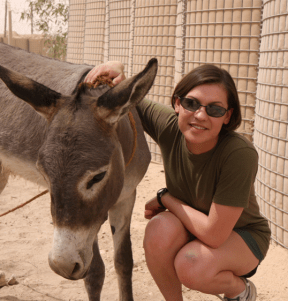

Early one August morning, Colonel Folsom awoke to a new sound. The thwap-thwap-thwap of the helicopters, the endless hum of the generators, those were the sounds of everyday life. This sound was different – the sound of braying donkey.

Early one August morning, Colonel Folsom awoke to a new sound. The thwap-thwap-thwap of the helicopters, the endless hum of the generators, those were the sounds of everyday life. This sound was different – the sound of braying donkey.

Before long, Smoke was a familiar sight around Camp Taqaddum. After long walks around the wire, Smoke learned to open doors and wander around. If you ever left that candy dish out on your desk, you were on your own.

Before long, Smoke was a familiar sight around Camp Taqaddum. After long walks around the wire, Smoke learned to open doors and wander around. If you ever left that candy dish out on your desk, you were on your own. Regulations prohibit the keeping of pets in a war zone. A Navy Captain helped get Smoke designated as a therapy animal, and he was home to stay. As it turned out, there was more than a little truth to the label. For young women and men thousands of miles from home in a war zone, the little animal was a welcome reminder of home.

Regulations prohibit the keeping of pets in a war zone. A Navy Captain helped get Smoke designated as a therapy animal, and he was home to stay. As it turned out, there was more than a little truth to the label. For young women and men thousands of miles from home in a war zone, the little animal was a welcome reminder of home. Colonel Folsom couldn’t get the little animal out of his head and, learning of his plight in 2010, determined to get him back. There were plenty of kids who had survived trauma of all kinds in his home state of Nebraska. Folsom believed that the animal could do them some good, as well.

Colonel Folsom couldn’t get the little animal out of his head and, learning of his plight in 2010, determined to get him back. There were plenty of kids who had survived trauma of all kinds in his home state of Nebraska. Folsom believed that the animal could do them some good, as well.

Today, The Seeing Eye operates a 330-acre complex in Morris Township, New Jersey, the oldest guide dog school still in operation, in the world. The primary breeds used for such training are German Shepherds, Labs, Golden Retrievers, and Lab/Golden mixed breeds. Boxers are occasionally used, for individuals with allergies.

Today, The Seeing Eye operates a 330-acre complex in Morris Township, New Jersey, the oldest guide dog school still in operation, in the world. The primary breeds used for such training are German Shepherds, Labs, Golden Retrievers, and Lab/Golden mixed breeds. Boxers are occasionally used, for individuals with allergies.

The camels arrived on May 14, 1856, and set out for the newly established Camp Verde in West Texas, with elements of the US Cavalry and seven handlers.

The camels arrived on May 14, 1856, and set out for the newly established Camp Verde in West Texas, with elements of the US Cavalry and seven handlers.

A few months later, a Salt River rancher named Cyrus Hamblin spotted the animal while rounding up cows. It was a camel, and Hamblin saw that it had something that looked like the skeleton of a man tied to its back. Nobody believed his story, but a group of prospectors fired on the animal several weeks later. Though their shots missed, they saw the animal bolt and run, and a human skull with some parts of flesh and hair still attached fell to the ground.

A few months later, a Salt River rancher named Cyrus Hamblin spotted the animal while rounding up cows. It was a camel, and Hamblin saw that it had something that looked like the skeleton of a man tied to its back. Nobody believed his story, but a group of prospectors fired on the animal several weeks later. Though their shots missed, they saw the animal bolt and run, and a human skull with some parts of flesh and hair still attached fell to the ground.

At the height of its depravity, the Khmere Rouge smashed the heads of infants and children against Chankiri (Killing) Trees so that they “wouldn’t grow up and take revenge for their parents’ deaths”. Soldiers laughed as they carried out these grim executions. Failure to do so would have shown sympathy, making the killer him/herself, a target.

At the height of its depravity, the Khmere Rouge smashed the heads of infants and children against Chankiri (Killing) Trees so that they “wouldn’t grow up and take revenge for their parents’ deaths”. Soldiers laughed as they carried out these grim executions. Failure to do so would have shown sympathy, making the killer him/herself, a target.

On May 12, the American flagged container ship SS Mayaguez passed the coast of Cambodia bound for Sattahip, in southwest Thailand. At 2:18pm, two fast patrol craft of the Khmere Rouge approached the vessel, firing machine guns and then rocket-propelled grenades across its bows.

On May 12, the American flagged container ship SS Mayaguez passed the coast of Cambodia bound for Sattahip, in southwest Thailand. At 2:18pm, two fast patrol craft of the Khmere Rouge approached the vessel, firing machine guns and then rocket-propelled grenades across its bows. The cargo vessel was being towed to Kompong Som on the Cambodian mainland, as word of the incident reached the White House. A government made to look weak and indecisive by what President Ford himself called the “humiliating withdrawal” of only days earlier, could ill afford another drawn-out hostage drama, similar to that of the USS Pueblo. Massive force would be brought to bear against the Khmere Rouge, and time was of the essence.

The cargo vessel was being towed to Kompong Som on the Cambodian mainland, as word of the incident reached the White House. A government made to look weak and indecisive by what President Ford himself called the “humiliating withdrawal” of only days earlier, could ill afford another drawn-out hostage drama, similar to that of the USS Pueblo. Massive force would be brought to bear against the Khmere Rouge, and time was of the essence. Expecting only light resistance, US forces were met with savage force on May 15, from a heavily armed contingent of some 150-200 Khmere Rouge. Three of the nine helicopters participating in the operation were shot down, and another four too heavily heavily damaged to continue

Expecting only light resistance, US forces were met with savage force on May 15, from a heavily armed contingent of some 150-200 Khmere Rouge. Three of the nine helicopters participating in the operation were shot down, and another four too heavily heavily damaged to continue The cost of the Mayaguez Incident, officially the last battle of the Vietnam war, was heavy. Eighteen Marines, Airmen and Navy corpsmen were killed or missing in the assault and evacuation of Kho-Tang Island. Another twenty-three were killed in a helicopter crash. The last of 230 Marines would not get out until well after dark.

The cost of the Mayaguez Incident, officially the last battle of the Vietnam war, was heavy. Eighteen Marines, Airmen and Navy corpsmen were killed or missing in the assault and evacuation of Kho-Tang Island. Another twenty-three were killed in a helicopter crash. The last of 230 Marines would not get out until well after dark.

Following liberation, French women were beaten and humiliated in the streets, their heads shaved, for being “collaborators” with their German occupiers.

Following liberation, French women were beaten and humiliated in the streets, their heads shaved, for being “collaborators” with their German occupiers.

Sixty-five years later, Jan Gregor of the East German state of Brandenburg, can still remember the day his mother told him that she’d been “made pregnant by force”. He was five, at the time.

Sixty-five years later, Jan Gregor of the East German state of Brandenburg, can still remember the day his mother told him that she’d been “made pregnant by force”. He was five, at the time.

Icelandic public opinion was sharply divided at the invasion and subsequent occupation. Some described this as the “blessað stríðið”, the “Lovely War”, and celebrated the building of roads, hospitals, harbors, airfields and bridges as a boon to the local economy. Many resented the occupation, which in some years equaled 50% of the native male population.

Icelandic public opinion was sharply divided at the invasion and subsequent occupation. Some described this as the “blessað stríðið”, the “Lovely War”, and celebrated the building of roads, hospitals, harbors, airfields and bridges as a boon to the local economy. Many resented the occupation, which in some years equaled 50% of the native male population.

You must be logged in to post a comment.