In the first full century of American independence, three great waves of European and later Asian immigrants left their homes in the ‘old country’, headed for a life in the new world.

Starvation, shipwreck and disease killed no fewer than 1 in 10 during the period 1790 – 1820, without any so much as setting foot in the new world. And still they came.

Starvation, shipwreck and disease killed no fewer than 1 in 10 during the period 1790 – 1820, without any so much as setting foot in the new world. And still they came.

The largest non-English speaking minority were the ethnic Germans, escaping economic hardship and in search of political freedom. At the time of the Civil War, nearly one-quarter of all Union troops were German Americans, some 45% of whom were born in Europe.

German migration rose faster than any other immigrant group through the latter part of the 19th century and into the 20th, many in pursuit of agricultural opportunity while others settled in major cities such as New York and Philadelphia.

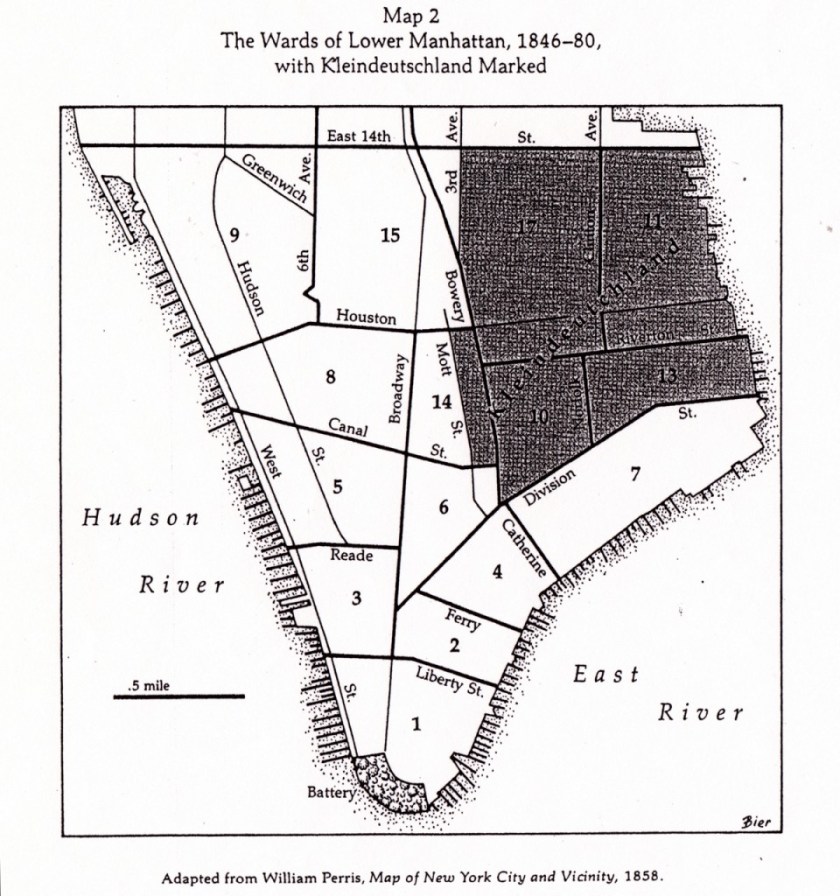

Kleindeutschland, or “Little Germany”, occupied some 400 blocks on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, in what is now the East Village. “Dutchtown”, as contemporary non-Germans called the area, was home to New York’s German immigrant community since the 1840s, when they first began to arrive in significant numbers. By 1855, New York had the largest ethnically German community in the world, save for Berlin and Vienna.

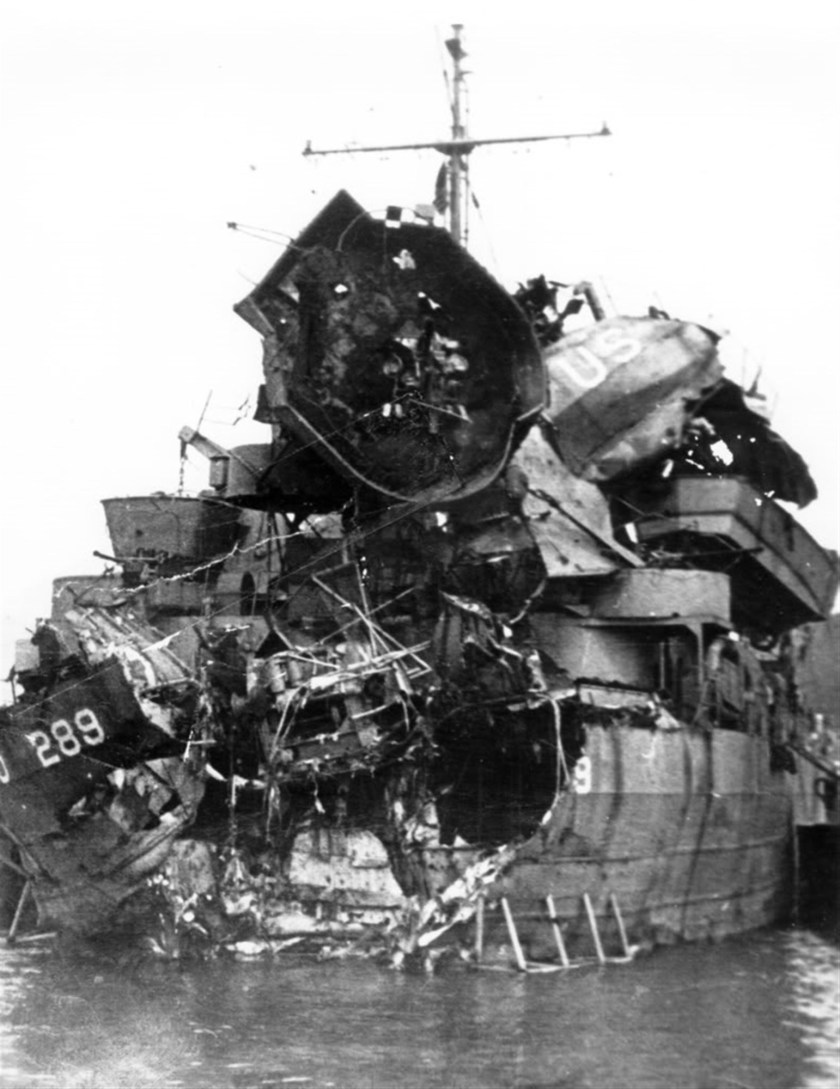

June 15, 1904 dawned bright and beautiful on Little Germany, a beautiful late spring morning when the sidewheel Passenger Steamboat General Slocum left the dock and steamed into the East River.

PS General Slocum was on a charter this day, carrying German-American families on an outing from St. Mark’s Lutheran Church on a harbor cruise and picnic. Over a thousand tickets were sold, not counting 300+ children who were sailing for free.

There were 1,342 people on board, mostly women and children, including band, crew and catering staff.

The fire probably started when someone tossed a cigarette or match into the forward section lamp room. The flames spread quickly, fueled by lamp oil and oily rags. A 12-year old boy first reported the fire, but the Captain didn’t believe him. The fire was first noticed at around 10:00am.

The ships’ operators had been woefully lax in maintaining safety equipment. Now it began to show. Fire hoses stored in the sun for years were uncoiled, only to break into rotten bits in the hands of the crew. Life preservers manufactured in 1891 had hung unprotected in the sun for 13 years, their canvas covers splitting apart pouring useless cork powder onto the floor. Survivors reported inaccessible life boats, wired and painted into place.

Crew members reported to Captain William van Schaick that the blaze “could not be conquered.” It was “like trying to put out hell itself.” The captain ran full steam into the wind trying to make it to the 134th Street Pier, but a tug boat waved them off, fearing the flames would spread to nearby buildings.

The wind and the speed of the ship itself whipped the flames into an inferno as Captain van Schaick changed course for North Brother Island, just off the Bronx’ shore.

Many jumped overboard to escape the inferno, but the heavy women’s clothing of the era quickly pulled them under.

Desperate mothers put useless life jackets on children and threw them overboard, only to watch in horror as they sank. One man, fully engulfed in flames, jumped screaming over the side, only to be swallowed whole by the massive paddle wheel.

One woman gave birth in the confusion, and then jumped overboard with her newborn to escape the flames. They both drowned.

A few small boats were successful in pulling alongside in the Hell’s Gate part of the harbor, but navigation was difficult due to the number of corpses already bobbing in the waves.

Holding his station despite the inferno, Captain van Schaick permanently lost sight in one eye and his feet were badly burned by the time he ran the Slocum aground at Brother Island.

Patients and staff at the local hospital formed a human chain to pull survivors to shore as they jumped into shallow water.

1,021 passengers and crew either burned to death, or drowned. It was the deadliest peacetime maritime disaster, in American history.

There were only 321 survivors.

The youngest survivor of the disaster was six-month-old Adella Liebenow. The following year at the age of one, Liebenow unveiled a memorial statue to the disaster which had killed her two sisters and permanently disfigured her mother.

The New York Times reported “Ten thousand persons saw through their tears a baby with a doll tucked under her arm unveil the monument to the unidentified dead of the Slocum disaster yesterday afternoon in the Lutheran Cemetery, Middle Village, L.I.”

Both of Liebenow’s sisters were among the unidentified dead.

The General Slocum disaster killed fewer than one per cent of the overall population of Little Germany, yet these were the women and children of some of the community’s most established families.

There were more than a few suicides. Mutual recriminations devoured much of a once-clannish community, as the men began to move away.

There was no longer anything for them, in that place.

Anti-German sentiment engendered by WW1 finished what the General Slocum disaster, had begun. Soon, New York’s German-immigrant community, was no more.

Deep inside the East Village, amidst the hipsters and the poets’ cafes of “Alphabet City”, stands a forgotten memorial. A 9′ stele erected in Tompkins Square Park, sculpted from pink Tennessee Marble. The relief sculpture shows two children, beside them are inscribed these words: “They were Earth’s purest children, young and fair.”

Once the youngest survivor of the disaster, Adella (Liebenow) Wotherspoon passed away in 2004, at the age of 100, the oldest survivor of the deadliest disaster in New York history. Until September 11, 2001.

If you enjoyed this “Today in History”, please feel free to re-blog, “like” & share on social media, so that others may find and enjoy it as well. Please click the “follow” button on the right, to receive email updates on new articles. Thank you for your interest, in the history we all share.

From the dawn of the 20th century, the Nobel Peace prize was awarded to individuals and organizations which have “done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.”

From the dawn of the 20th century, the Nobel Peace prize was awarded to individuals and organizations which have “done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.” Great Uncle Jacob Deppin was also there at Appomattox, wearing Blue. He served for the duration, save for the year and one-half spent in captivity.

Great Uncle Jacob Deppin was also there at Appomattox, wearing Blue. He served for the duration, save for the year and one-half spent in captivity.

Lafayette’s wife Adrienne gave birth to their first child on one such visit, a baby boy the couple would name Georges Washington Lafayette.

Lafayette’s wife Adrienne gave birth to their first child on one such visit, a baby boy the couple would name Georges Washington Lafayette.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Lou Gehrig collapsed in 1939 spring training, going into an abrupt decline early in the season. The Yankees were in Detroit on May 2 when Gehrig told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end.

Lou Gehrig collapsed in 1939 spring training, going into an abrupt decline early in the season. The Yankees were in Detroit on May 2 when Gehrig told manager Joe McCarthy “I’m benching myself, Joe”. It’s “for the good of the team”. McCarthy put Babe Dahlgren in at first and the Yankees won 22-2, but that was it. The Iron Horse’s streak of 2,130 consecutive games, had come to an end.

Boston was all but an island in those days, connected to the mainland only be a narrow “neck” of land. A Patriot force some 20,000 strong took positions in the days and weeks that followed, blocking the city and trapping four regiments of British troops (about 4,000 men) inside of the city.

Boston was all but an island in those days, connected to the mainland only be a narrow “neck” of land. A Patriot force some 20,000 strong took positions in the days and weeks that followed, blocking the city and trapping four regiments of British troops (about 4,000 men) inside of the city.

A group of Machias men approached Margaretta from the land and demanded her surrender, but Moore lifted anchor and sailed off in attempt to recover the Polly. A turn of his stern through a brisk wind resulted in a boom and gaff breaking away from the mainsail, crippling the vessel’s navigability. Unity gave chase followed by Falmouth.

A group of Machias men approached Margaretta from the land and demanded her surrender, but Moore lifted anchor and sailed off in attempt to recover the Polly. A turn of his stern through a brisk wind resulted in a boom and gaff breaking away from the mainsail, crippling the vessel’s navigability. Unity gave chase followed by Falmouth.

The women and children of Oradour-sur-Glane were locked in a village church while German soldiers looted the town. The men were taken to a half-dozen barns and sheds, where the machine guns were already set up.

The women and children of Oradour-sur-Glane were locked in a village church while German soldiers looted the town. The men were taken to a half-dozen barns and sheds, where the machine guns were already set up. Nazi soldiers then lit an incendiary device in the church, and gunned down 247 women and 205 children as they tried to escape.

Nazi soldiers then lit an incendiary device in the church, and gunned down 247 women and 205 children as they tried to escape.

French President Jacques Chirac dedicated a memorial museum in 1999, the “Centre de la mémoire d’Oradour“. The village stands today as those Nazi soldiers left it, seventy-four years ago today. It may be the most forlorn place on earth.

French President Jacques Chirac dedicated a memorial museum in 1999, the “Centre de la mémoire d’Oradour“. The village stands today as those Nazi soldiers left it, seventy-four years ago today. It may be the most forlorn place on earth. a summer day in 1944. . . The soldiers came. Nobody lives here now. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years. . . was dead. This is Oradour-sur-Glane, in France. The day the soldiers came, the people were gathered together. The men were taken to garages and barns, the women and children were led down this road . . . and they were driven. . . into this church. Here, they heard the firing as their men were shot. Then. . . they were killed too. A few weeks later, many of those who had done the killing were themselves dead, in battle. They never rebuilt Oradour. Its ruins are a memorial. Its martyrdom stands for thousands upon thousands of other martyrdoms in Poland, in Russia, in Burma, in China, in a World at War”.

a summer day in 1944. . . The soldiers came. Nobody lives here now. They stayed only a few hours. When they had gone, the community which had lived for a thousand years. . . was dead. This is Oradour-sur-Glane, in France. The day the soldiers came, the people were gathered together. The men were taken to garages and barns, the women and children were led down this road . . . and they were driven. . . into this church. Here, they heard the firing as their men were shot. Then. . . they were killed too. A few weeks later, many of those who had done the killing were themselves dead, in battle. They never rebuilt Oradour. Its ruins are a memorial. Its martyrdom stands for thousands upon thousands of other martyrdoms in Poland, in Russia, in Burma, in China, in a World at War”.

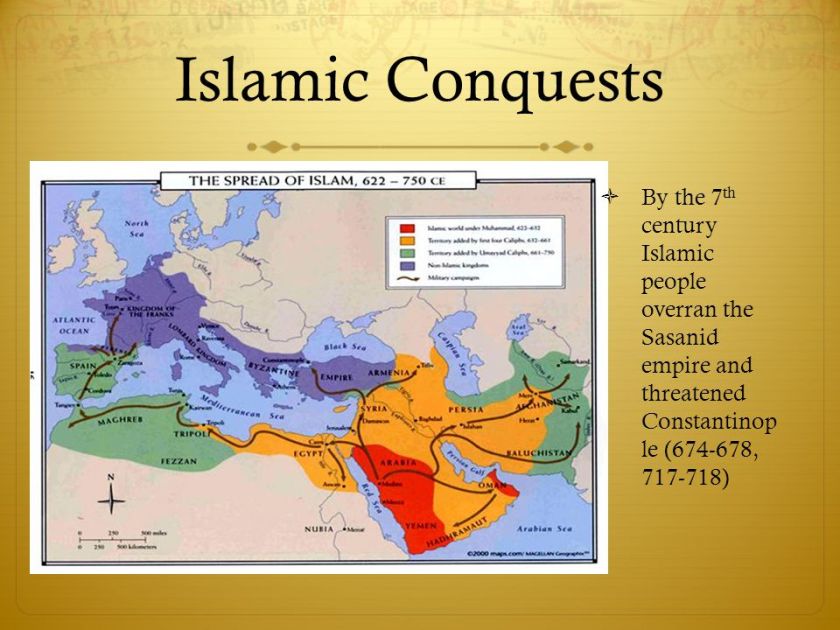

One of those to escape with his life, was a young Abd Ar-Rahman al Ghafiqi. Eleven years later in 732, the now – governor of Al-Andalus would once again cross the Pyrenees, this time at the head of a massive army of his own. Al Ghafiqi’s legions laid waste to Navarre and Gascony, first destroying Auch, and then Bordeaux. Duke Odo “The Great” would be destroyed at the River Garonne and the table set for the all-important decision of Tours.

One of those to escape with his life, was a young Abd Ar-Rahman al Ghafiqi. Eleven years later in 732, the now – governor of Al-Andalus would once again cross the Pyrenees, this time at the head of a massive army of his own. Al Ghafiqi’s legions laid waste to Navarre and Gascony, first destroying Auch, and then Bordeaux. Duke Odo “The Great” would be destroyed at the River Garonne and the table set for the all-important decision of Tours.

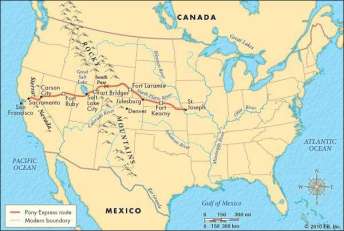

across the Isthmus of Panama or the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in Mexico. The simmering tensions which would lead the nation to Civil War would prove such a system inadequate, as the rapid transfer of information became ever more important.

across the Isthmus of Panama or the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, in Mexico. The simmering tensions which would lead the nation to Civil War would prove such a system inadequate, as the rapid transfer of information became ever more important. The Pony Express compressed the standard 24-day schedule for overland delivery to ten days, but the system was a financial disaster. Little more than an expensive stopgap before the first transcontinental telegraph system.

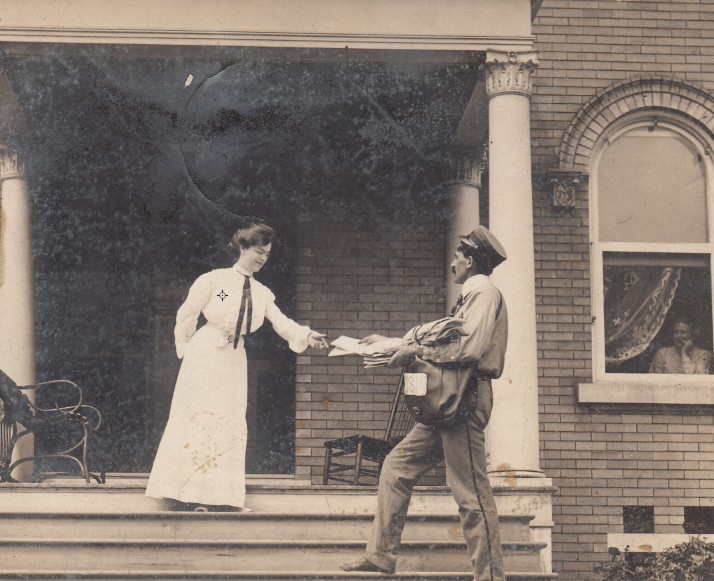

The Pony Express compressed the standard 24-day schedule for overland delivery to ten days, but the system was a financial disaster. Little more than an expensive stopgap before the first transcontinental telegraph system. The first mail carried through the air arrived by hot air balloon on January 7, 1785, a letter written by Loyalist William Franklin to his son William Temple Franklin, at that time serving a diplomatic role in Paris with his grandfather, the United States’ one-time and first postmaster, Benjamin Franklin.

The first mail carried through the air arrived by hot air balloon on January 7, 1785, a letter written by Loyalist William Franklin to his son William Temple Franklin, at that time serving a diplomatic role in Paris with his grandfather, the United States’ one-time and first postmaster, Benjamin Franklin.

The Regulus was superseded by the Polaris missile in 1964, the year in which Barbero ended her nuclear strategic deterrent patrols. She was struck from the Naval Registry that July, and suffered the humiliating fate of the target ship, sunk off the coast of Pearl Harbor on October 7 by the nuclear submarine USS Swordfish.

The Regulus was superseded by the Polaris missile in 1964, the year in which Barbero ended her nuclear strategic deterrent patrols. She was struck from the Naval Registry that July, and suffered the humiliating fate of the target ship, sunk off the coast of Pearl Harbor on October 7 by the nuclear submarine USS Swordfish.

In the late 19th century, Europe was embarked on yet another of its depressingly regular paroxysms of anti-Semitism, when a French Captain of Jewish Alsatian extraction by the name of Alfred Dreyfus was arrested, for selling state secrets to Imperial Germany.

In the late 19th century, Europe was embarked on yet another of its depressingly regular paroxysms of anti-Semitism, when a French Captain of Jewish Alsatian extraction by the name of Alfred Dreyfus was arrested, for selling state secrets to Imperial Germany. Chief Inspector Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Armand Auguste Ferdinand Mercier du Paty de Clam, himself no handwriting expert, agreed with Bertillon. With no file to go on and despite the feebleness of the evidence, de Clam summoned Dreyfus for interrogation on October 13, 1894.

Chief Inspector Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Armand Auguste Ferdinand Mercier du Paty de Clam, himself no handwriting expert, agreed with Bertillon. With no file to go on and despite the feebleness of the evidence, de Clam summoned Dreyfus for interrogation on October 13, 1894.

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus. The public outcry became furious in January 1898 when author Émile Zola published a bitter denunciation in an open letter to the Paris press, entitled “J’accuse” (I Blame).

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus. The public outcry became furious in January 1898 when author Émile Zola published a bitter denunciation in an open letter to the Paris press, entitled “J’accuse” (I Blame).

You must be logged in to post a comment.