During the twentieth century, the United States and others specially recruited bilingual speakers of obscure languages, then applying those skills in secret communications based on those languages. Among these, the story of the Navajo “Code Talkers” are probably best known. Theirs was a language with no alphabet or symbols, a language with such complex syntax and tonal qualities as to be unintelligible to the non-speaker. The military code based on such a language proved unbreakable in WWII. Japanese code breakers never got close.

The United States Marine Corps recruited some 4-500 Navajo speakers, who served in all six Marine divisions in the Pacific theater. Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Peleliu, Iwo Jima: Navajo code talkers took part in every assault conducted by the United States Marine Corps, from 1942 to ‘45.

The history of the Navajo code talkers of WWII is relatively well known, but by no means, unique. Indigenous Americans of other nations served as code talkers in WW2, including Assiniboine, Lakota and Meskwaki soldiers, who did service in the Pacific, North African, and European theaters of the war.

The history of the Navajo code talkers of WWII is relatively well known, but by no means, unique. Indigenous Americans of other nations served as code talkers in WW2, including Assiniboine, Lakota and Meskwaki soldiers, who did service in the Pacific, North African, and European theaters of the war.

Fourteen Comanche soldiers took part in the Normandy landings. As with the Navajo, these substituted phrases when their own language lacked a proper term. Thus, “tank” became “turtle”. “Bombers” became “pregnant airplanes”. Adolf Hitler was “Crazy White Man”.

The information is contradictory, but Basque may also have been put to use, in areas where no native speakers were believed to be present. Native Cree speakers served with Canadian Armed Services, though oaths of secrecy have all but blotted their contributions, from the pages of history.

The first documented use of military codes based on native American languages took place during the Second Battle of the Somme in September of 1918, employing on the language skills of a number of Cherokee troops.

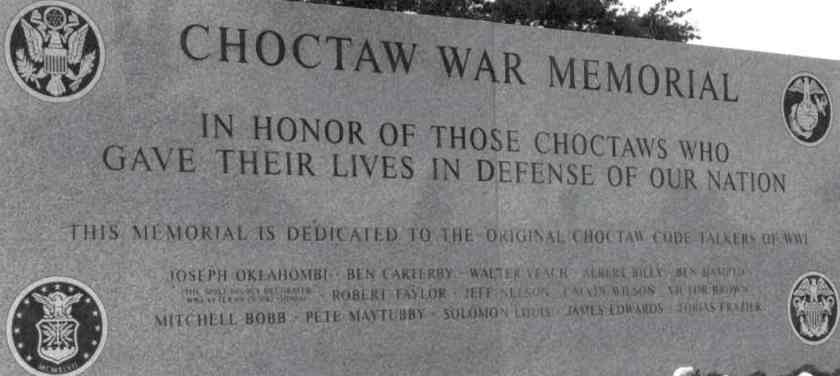

The government of Choctaw nation will tell you otherwise, contending that Theirs was the first native language, used in this way. Late in 1917, Colonel Alfred Wainwright Bloor was serving in France with the 142nd Infantry Regiment. They were a Texas outfit, constituted in May of that year and including a number of Oklahoma Choctaws.

The Allies had already learned the hard way that their German adversaries spoke excellent English, and had already intercepted and broken several English-based codes. Colonel Bloor heard two of his Choctaw soldiers talking to each other, and realized he didn’t have the foggiest notion of what they were saying. If he didn’t understand their conversation, the Germans wouldn’t have a clue.

The first test under combat conditions took place on October 26, 1918, as two companies of the 2nd Battalion performed a “delicate” withdrawal from Chufilly to Chardeny, in the Champagne sector. A captured German officer later confirmed the Choctaw code to have been a complete success. We were “completely confused by the Indian language”, he said, “and gained no benefit whatsoever” from wiretaps.

Choctaw soldiers were placed in multiple companies of infantry. Messages were transmitted via telephone, radio and by runner, many of whom were themselves native Americans.

As in the next war, Choctaw would improvise when their language lacked the proper word or phrase. When describing artillery, they used the words for “big gun”. Machine guns were “little gun shoot fast”.

The Choctaw themselves didn’t use the term “Code Talker”, that wouldn’t come along until WWII. At least one member of the group, Tobias W. Frazier, simply described what they did as, “talking on the radio”. Of the 19 who served in WWI, 18 were native Choctaw from southeast Oklahoma. The last was a native Chickasaw. The youngest was Benjamin Franklin Colbert, Jr., the son of Benjamin Colbert Sr., one of Teddy Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” of the Spanish American War. Born September 15, 1900 in the Durant Indian Territory, he was all of sixteen, the day he enlisted.

The Choctaw themselves didn’t use the term “Code Talker”, that wouldn’t come along until WWII. At least one member of the group, Tobias W. Frazier, simply described what they did as, “talking on the radio”. Of the 19 who served in WWI, 18 were native Choctaw from southeast Oklahoma. The last was a native Chickasaw. The youngest was Benjamin Franklin Colbert, Jr., the son of Benjamin Colbert Sr., one of Teddy Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” of the Spanish American War. Born September 15, 1900 in the Durant Indian Territory, he was all of sixteen, the day he enlisted.

Another was Choctaw Joseph Oklahombi, whose name means “man killer” in the Choctaw language. Six days before Sergeant York’s famous capture of 132 Germans in the Argonne Forest, Joseph Oklahombi charged a strongly held German position, single-handed. Oklahombi‘s Croix de Guerre citation, personally awarded him by Marshall Petain, tells the story:

“Under a violent barrage, [Pvt. Oklahombi] dashed to the attack of an enemy position, covering about 210 yards through barbed-wire entanglements. He rushed on machine-gun nests, capturing 171 prisoners. He stormed a strongly held position containing more than 50 machine guns, and a number of trench mortars. Turned the captured guns on the enemy, and held the position for four days, in spite of a constant barrage of large projectiles and of gas shells. Crossed no man’s land many times to get information concerning the enemy, and to assist his wounded comrades”.

Unconfirmed eyewitness accounts report that 250 Germans occupied the position, and that Oklahombi killed 79 of them before their comrades decided it was wiser to surrender. Some guys are not to be trifled with.

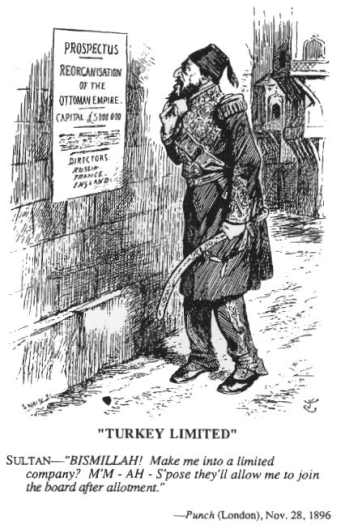

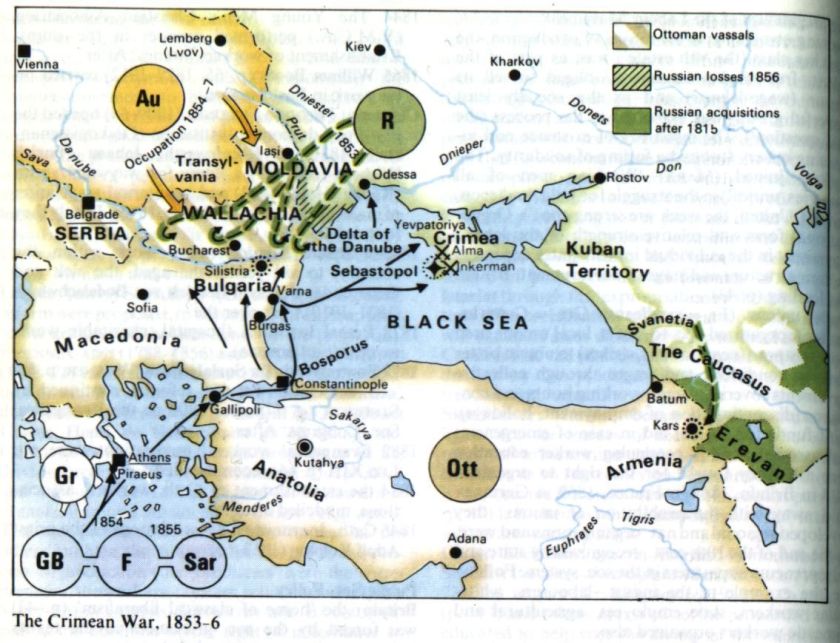

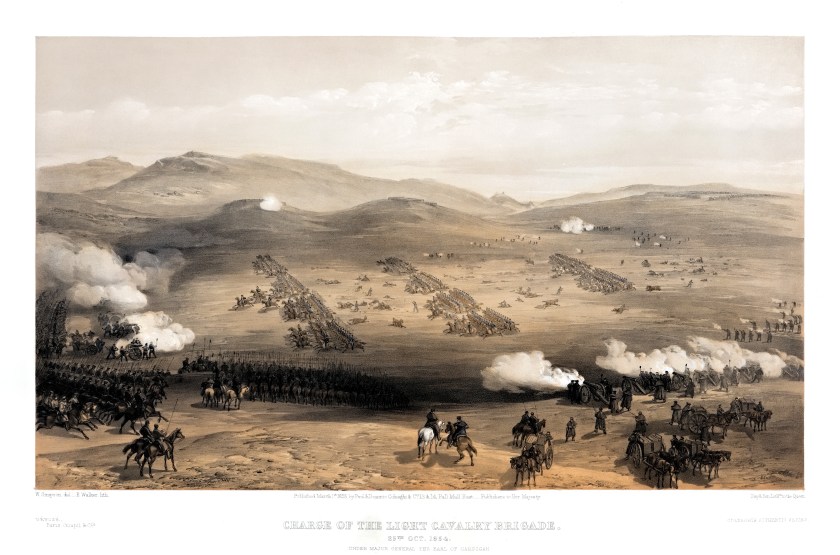

The Battle of Balaclava opened shortly after 5:00am on this day in 1854, when a squadron of Russian Cossack Cavalry advanced under cover of darkness. The Cossacks were followed by a host of Uhlans, their Polish light cavalry allies, against several dug-in positions occupied by Ottoman Turks. The Turks fought stubbornly, sustaining 25% casualties before finally being forced to withdraw.

The Battle of Balaclava opened shortly after 5:00am on this day in 1854, when a squadron of Russian Cossack Cavalry advanced under cover of darkness. The Cossacks were followed by a host of Uhlans, their Polish light cavalry allies, against several dug-in positions occupied by Ottoman Turks. The Turks fought stubbornly, sustaining 25% casualties before finally being forced to withdraw.

Harding’s Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon, believed that money was driven underground or overseas as income tax rates increased. Mellon held the heretical belief for that time, that lower tax rates led to greater levels of economic activity and that, as people had more of their own money to work with, increased activity resulted in higher tax revenues.

Harding’s Treasury Secretary, Andrew Mellon, believed that money was driven underground or overseas as income tax rates increased. Mellon held the heretical belief for that time, that lower tax rates led to greater levels of economic activity and that, as people had more of their own money to work with, increased activity resulted in higher tax revenues.

Fears of the Smoot-Hawley tariff act fueled a further contraction in the following weeks, for apparently good reason. When President Hoover signed the protectionist measure into law in 1930, American imports and exports plunged by more than half.

Fears of the Smoot-Hawley tariff act fueled a further contraction in the following weeks, for apparently good reason. When President Hoover signed the protectionist measure into law in 1930, American imports and exports plunged by more than half.

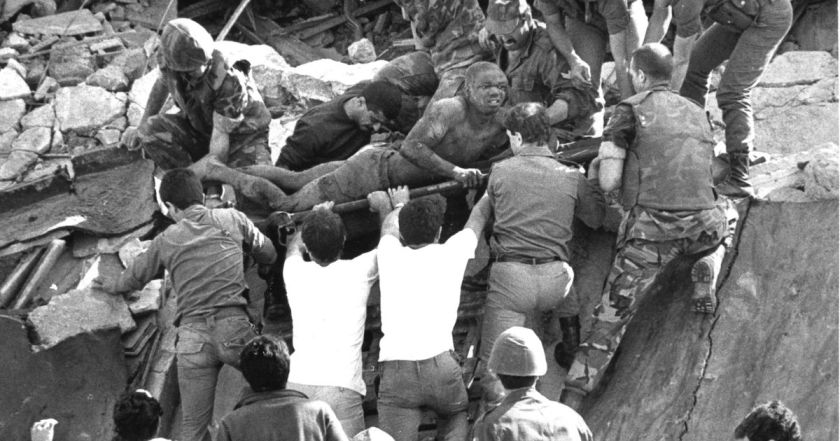

A Lebanese cedar tree grows in the green expanse of section 59 at Arlington National Cemetery, marking the final resting place of twenty-one honored dead, among the first Americans to die in the global war against Islamist terrorism. A fight which continues, to this day.

A Lebanese cedar tree grows in the green expanse of section 59 at Arlington National Cemetery, marking the final resting place of twenty-one honored dead, among the first Americans to die in the global war against Islamist terrorism. A fight which continues, to this day.

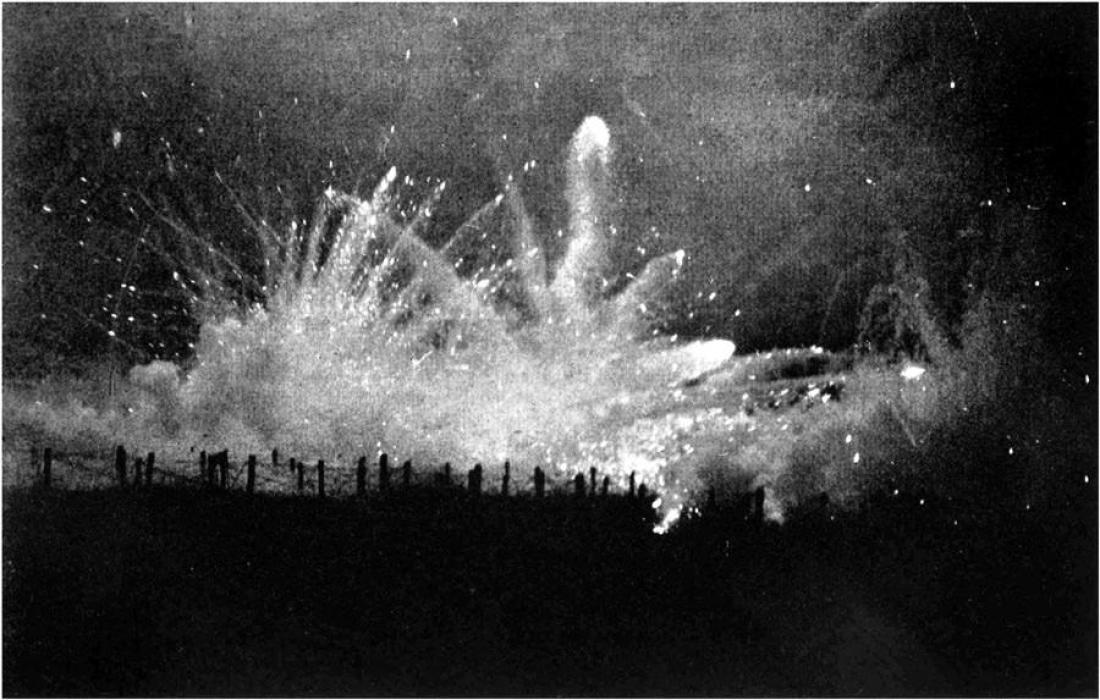

Doubt has been cast on the “Myth of Langemarck”, and the tragic bravery of idealistic German boys, happily defending the Fatherland. The numbers of dead and maimed are real enough, but most reservists were in fact comprised of older working class men, not the fresh-faced youth, of the Kindermord. Be that as it may, a story must be told. Excuses must be made to the home team, for the crushing failure of the War of Movement, and the four-year war of attrition, to follow.

Doubt has been cast on the “Myth of Langemarck”, and the tragic bravery of idealistic German boys, happily defending the Fatherland. The numbers of dead and maimed are real enough, but most reservists were in fact comprised of older working class men, not the fresh-faced youth, of the Kindermord. Be that as it may, a story must be told. Excuses must be made to the home team, for the crushing failure of the War of Movement, and the four-year war of attrition, to follow.

First raised above the town square on October 19, 1774, the flag’s canton featured the Union Jack, on the blood red field of the British Red Ensign. The

First raised above the town square on October 19, 1774, the flag’s canton featured the Union Jack, on the blood red field of the British Red Ensign. The

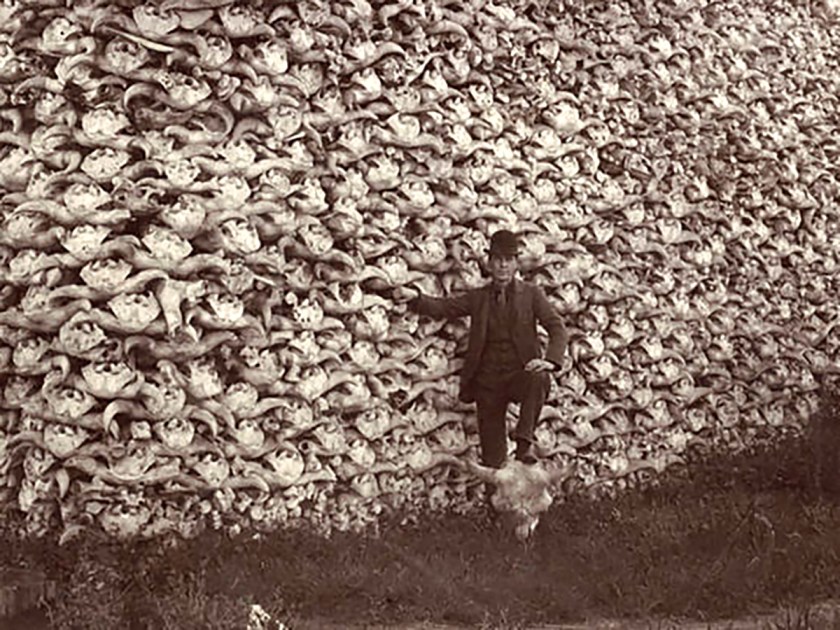

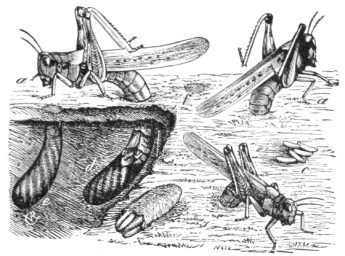

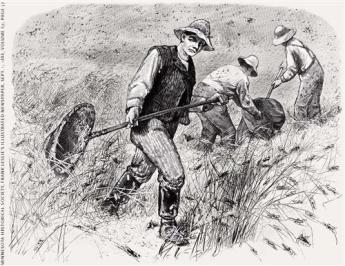

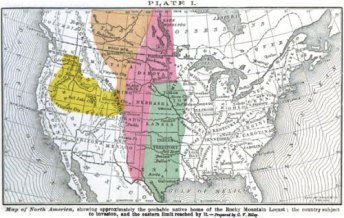

Farmers used gunpowder, fire and water, anything they could think of, to destroy what could only be seen as a plague of biblical proportion. They smeared them with “hopperdozers”, a plow-like device pulled behind horses, designed to knock jumping locusts into a pan of liquid poison or fuel, or even sucking them into vacuum cleaner-like contraptions.

Farmers used gunpowder, fire and water, anything they could think of, to destroy what could only be seen as a plague of biblical proportion. They smeared them with “hopperdozers”, a plow-like device pulled behind horses, designed to knock jumping locusts into a pan of liquid poison or fuel, or even sucking them into vacuum cleaner-like contraptions. And then the locust went away, and no one is entirely certain, why. It is theorized that plowing, irrigation and harrowing destroyed up to 150 egg cases per square inch, in the years between swarms. Great Plains settlers, particularly those alongside the Mississippi river, appear to have disrupted the natural life cycle. Winter crops, particularly wheat, enabled farmers to “beat them to the punch”, putting away stockpiles of food before the pestilence reached the swarming phase.

And then the locust went away, and no one is entirely certain, why. It is theorized that plowing, irrigation and harrowing destroyed up to 150 egg cases per square inch, in the years between swarms. Great Plains settlers, particularly those alongside the Mississippi river, appear to have disrupted the natural life cycle. Winter crops, particularly wheat, enabled farmers to “beat them to the punch”, putting away stockpiles of food before the pestilence reached the swarming phase.

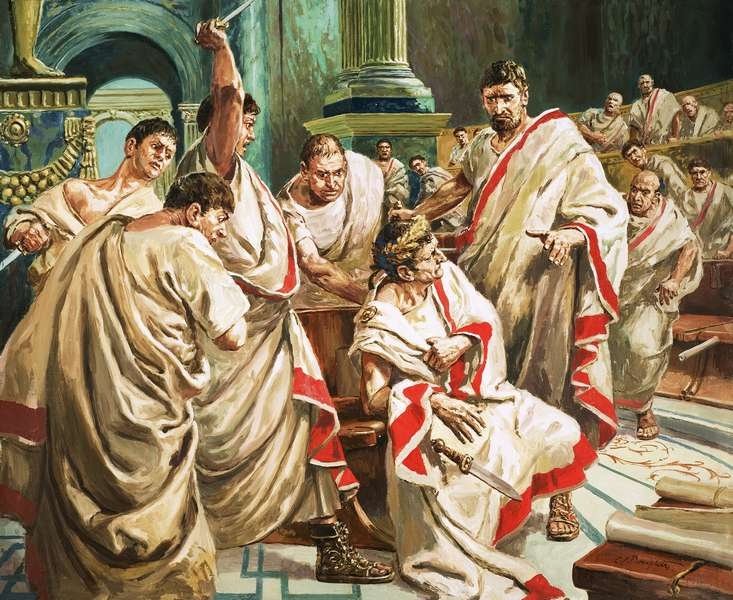

A series of civil wars and other events took place during the first century B.C., ending the Republican period and leaving in its wake an Imperium, best remembered for its long line of dictators.

A series of civil wars and other events took place during the first century B.C., ending the Republican period and leaving in its wake an Imperium, best remembered for its long line of dictators.

Brutus was 41 on the 15th of March, 44 B.C. The “Ides of March”. Caesar was 56. The Emperor’s dying words are supposed to have been “Et tu, Brute?”, as Brutus plunged the dagger in. “And you, Brutus?” But that’s not what he said. Those words were put into his mouth 1,643 years later, by William Shakespeare.

Brutus was 41 on the 15th of March, 44 B.C. The “Ides of March”. Caesar was 56. The Emperor’s dying words are supposed to have been “Et tu, Brute?”, as Brutus plunged the dagger in. “And you, Brutus?” But that’s not what he said. Those words were put into his mouth 1,643 years later, by William Shakespeare.

The Meux’s Brewery Co Ltd, established in 1764, was a London brewery owned by Sir Henry Meux. What the Times article was describing was a 22′ high monstrosity, held together by 29 iron hoops.

The Meux’s Brewery Co Ltd, established in 1764, was a London brewery owned by Sir Henry Meux. What the Times article was describing was a 22′ high monstrosity, held together by 29 iron hoops. The brewery was located in the crowded slum of St. Giles, where many homes contained several people to the room.

The brewery was located in the crowded slum of St. Giles, where many homes contained several people to the room. One brewery worker was able to save his brother from drowning in the flood, but others weren’t so lucky.

One brewery worker was able to save his brother from drowning in the flood, but others weren’t so lucky. In the days that followed, the crushing poverty of the slum led some to exhibit the corpses of their family members, charging a fee for anyone who wanted to come in and see. In one house, too many people crowded in and the floor collapsed, plunging them all into a cellar full of beer.

In the days that followed, the crushing poverty of the slum led some to exhibit the corpses of their family members, charging a fee for anyone who wanted to come in and see. In one house, too many people crowded in and the floor collapsed, plunging them all into a cellar full of beer.

You must be logged in to post a comment.