Jessica McClure Morales is a West Texas Mother of two school-age children. Her life is normal in every way. She’s a teacher’s aide. Her husband Danny, works for a piping supply outfit. Just a normal Texas Mom, with two kids and a puppy, playing in the yard.

On this day in 1987, Jessica McClure’s life was anything but normal. Frightened and alone, “Baby Jessica” was stuck twenty-two feet down, at the bottom of a well.

On this day in 1987, Jessica McClure’s life was anything but normal. Frightened and alone, “Baby Jessica” was stuck twenty-two feet down, at the bottom of a well.

Everything seemed so normal that Wednesday, October 14, just an eighteen-month-old baby girl, playing in the back yard of an Aunt. That old well pipe shouldn’t have been left open, but what harm could it do. The thing was only eight inches wide.

And then the baby disappeared. Down the well.

The language does not contain a word adequate to describe the horror that young mother must have felt, looking down that pipe.

Midland Fire and Police Departments devised the plan. A second shaft would be dug, parallel to the well. Then to bore a tunnel, until rescuers reached the baby. The operation would be over, by dinnertime.

The rescue proved far more difficult than first imagined. The first tools brought on-scene, were inadequate to get through the hard rock surrounding the well. What should have taken minutes, was turning to hours.

Television cameras were quick to arrive and covered the ordeal, live. Those of us of a certain age remember it well. The rescue was carried from the Netherlands to Brazil, from Germany to Hong Kong and mainland China. Well wishers called in to local television stations, from the Soviet Union. It seemed the whole world, stopped to watch.

Watching the evening news, it’s sometimes easy to believe that the world is going to hell. It’s not. What we saw for those fifty-eight hours was the True heroism and fundamental decency of every-day guys: fathers, sons and brothers, doing what they needed to do. We’d see it again in a New York Minute, should circumstances require.

You could watch it happen, around the clock. Many of us did. I remember it, each would dig until he’d drop, and then another man would take his place. There were out-of-work oil field workers and everyday guys. Mining engineers and paramedics. The work was frenetic and distraught, and at the same time, agonizingly slow.

Anyone who’s used a jackhammer, knows it’s not a tool designed to be used, sideways. Even so, they tried. A waterjet became a vital part of the rescue, a new and unproven technology, in 1987.

The sun went down that Wednesday and rose the following day and then it set, and still, the nightmare dragged on.

The sun went down that Wednesday and rose the following day and then it set, and still, the nightmare dragged on.

A microphone was lowered down, so doctors could hear her breathe. She would cry, and sometimes she would sing. A small voice drifting up from that hole in the ground, the words of “Winnie the Pooh”.

Both were good signs. A baby could neither sing nor cry, if she could not breathe.

The final tunneling phase of the operation could only be described, as a claustrophobic nightmare. An unimaginable ordeal. Midland Fire Department paramedic Robert O’Donnell was chosen, because of his small, wiry frame. Slathered all over with K-Y jelly and jammed into a space so tight it was difficult to breathe, O’Donnell inched his way through that black hole that Thursday night and into the small hours of Friday morning, until finally, he touched her leg.

The agony of those minutes that dragged on to hours can only be imagined. What he was trying to do, could not be done. In the end, O’Donnell was forced to back out of the hole, defeated. Empty handed. As they went back to work enlarging the tunnel, the paramedic sat on a curb, and wept.

On the second attempt, O’Donnell was able wrestle the baby out of that tiny space, handing her to fellow paramedic Steve Forbes, who carried her to safety.

Baby Jessica came out of that well with her face deeply scarred, and toes turned to gangrene, for lack of blood flow. She would require fifteen surgeries before it was over but, she was alive.

Media saturation coverage led then-President Ronald Reagan to quip, that “everybody in America became godmothers and godfathers of Jessica while this was going on.” Baby Jessica appeared with her teenage parents on Live with Regis and Kathie Lee, to talk about the incident. Scott Shaw of the Odessa American won the Pulitzer prize for the photograph, and ABC made a television movie: Everybody’s Baby: The Rescue of Jessica McClure. USA Today ranked her 22nd on a list of “25 lives of indelible impact.” Everyone in the story became famous. Until they weren’t.

In time, the scars healed for Jessica McClure. Today she has no recollection of those fifty-eight hours. Not so much the hero from the bottom of that hole, Robert O’Donnell. Whatever personal hell the man went through that night, alone in that blackest of places, never left his mind. And then there was the fame. And the adulation. And then, nothing.

Even now, we struggle to understand Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, (PTSD), a condition which ends the lives of twenty-two of the best among us every day, and has killed more Vietnam combat veterans, than the war itself. It was only 1987, when the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders dropped the requirement, that stressors be outside the range of normal human experience.

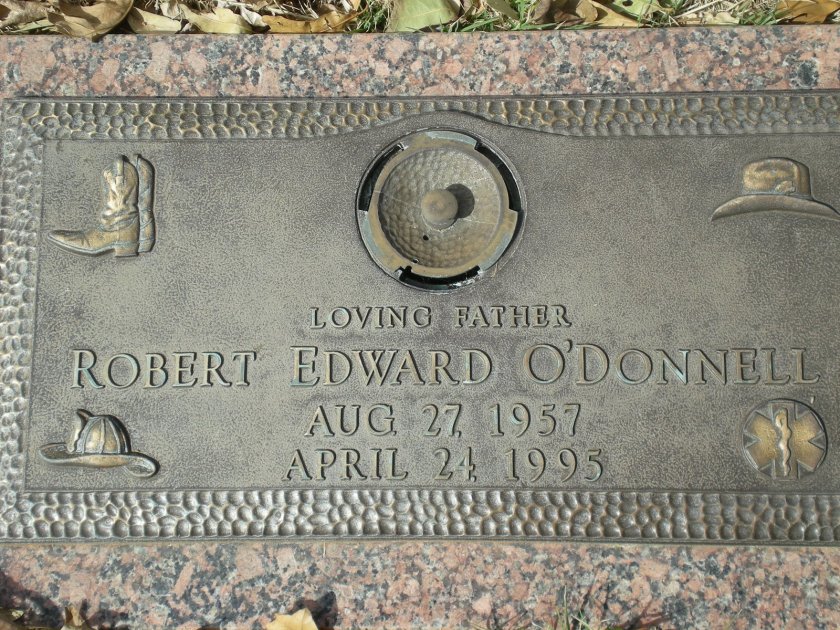

Robert O’Donnel took his own life on April 24, 1995. The media declined to notice. The stone above his grave bears the images of a cowboy hat and boots, and those of a fire hat, and the six-pointed Star of Life, symbol for emergency medical services, in nations the world over. A “Loving Father,” who has earned the right to be remembered.

Murphy’s company commander thought he wasn’t big enough for infantry service, and attempted to transfer him to cook and bakers’ school. Murphy refused. He wanted to be a combat soldier.

Murphy’s company commander thought he wasn’t big enough for infantry service, and attempted to transfer him to cook and bakers’ school. Murphy refused. He wanted to be a combat soldier. He was still in the hospital when his unit moved into the Vosges Mountains, in Eastern France.

He was still in the hospital when his unit moved into the Vosges Mountains, in Eastern France. “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”.

“Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”. The man who had once been judged too small to fight was one of the most decorated American combat soldiers of WW2, having received every military combat award for valor the United States Army has to give, plus additional awards for heroism, from France and from Belgium.

The man who had once been judged too small to fight was one of the most decorated American combat soldiers of WW2, having received every military combat award for valor the United States Army has to give, plus additional awards for heroism, from France and from Belgium.

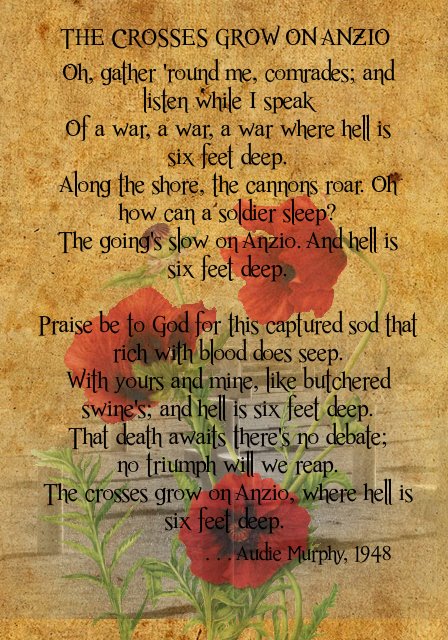

Joining the 3rd Infantry Division of George S. Patton’s 7th Army, Murphy participated in amphibious landings in Sicily in July, fighting in nearly every aspect of the Italian campaign. From Palermo to Messina and on to Naples, Anzio and Rome, the Germans were driven out of the Italian peninsula in savage and near continuous fighting that killed a member of my own family. By mid-December, the 3rd ID suffered 683 dead, 170 missing, and 2,412 wounded. Now Sergeant Murphy was there for most of it, excepting two periods when he was down with malaria.

Joining the 3rd Infantry Division of George S. Patton’s 7th Army, Murphy participated in amphibious landings in Sicily in July, fighting in nearly every aspect of the Italian campaign. From Palermo to Messina and on to Naples, Anzio and Rome, the Germans were driven out of the Italian peninsula in savage and near continuous fighting that killed a member of my own family. By mid-December, the 3rd ID suffered 683 dead, 170 missing, and 2,412 wounded. Now Sergeant Murphy was there for most of it, excepting two periods when he was down with malaria. “Colmar Pocket” was an 850 square mile area held by German troops: Murphy described it as “a huge and dangerous bridgehead thrusting west of the Rhine like an iron fist. Fed with men and materiel from across the river, it is a constant threat to our right flank; and potentially it is a perfect springboard from which the enemy could start a powerful counterattack.”

“Colmar Pocket” was an 850 square mile area held by German troops: Murphy described it as “a huge and dangerous bridgehead thrusting west of the Rhine like an iron fist. Fed with men and materiel from across the river, it is a constant threat to our right flank; and potentially it is a perfect springboard from which the enemy could start a powerful counterattack.” Let Murphy’s Medal of Honor Citation describe what happened next: “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”.

Let Murphy’s Medal of Honor Citation describe what happened next: “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”. Hollywood and, until his death in a plane crash in 1971, his post-war life was never free of it.

Hollywood and, until his death in a plane crash in 1971, his post-war life was never free of it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.