Dr. Stanislaw Krzyżanowski was a physician treating mostly the poorer Jewish families in the central Polish town of Otwock, 14 miles southeast of Warsaw. He had once said to his only daughter Irena: “If you see someone drowning, you must save them.” “But, what if I can’t swim?” she asked. “Nevertheless, you must try”.

Overwhelmed by the typhus epidemic of 1917, Dr. Krzyżanowski contracted the disease himself and died that February, but his example guided his daughter for the rest of her life. Jewish community leaders showed their gratitude by offering to pay for Irena’s education, but her mother declined.

Irena (Krzyżanowski) Sendler was a nurse living outside Warsaw, when Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939. The Nazis gathered up every Jew they could find in 1940, penning 400,000 or more up in the city. Soon, the Warsaw ghetto became the scene of suffering, disease and starvation. Knowing the Nazis feared nothing so much as Typhus, Sendler took advantage of their fears and obtained permission to begin work in the ghetto.

She would travel there daily, and soon started to smuggle Jewish babies out in the bottom of a medical bag. She’d place soiled bandages around and over sedated babies, to keep guards from looking too closely. She carried a burlap sack in the back of her truck. Sometimes she’d use that or even a coffin to smuggle larger children and even teenagers out of the ghetto, other times leading them out through cellars or sewers.

Sendler traveled with a small a dog she had trained to bark at Nazi soldiers letting her in and out of the gates. They wanted nothing to do with her small, yappy dog, and the barking would cover any sounds that the babies might make.

She would make as many as three runs a day, taking out as many as 6 children. Most of them were already orphans by this time, their parents murdered by the Nazi regime. Many times, parents gave up their children in order to save them.

Irena coded the names of these children onto two slips of paper, including false and real names. These she buried in glass jars under a tree in the yard of a friend. She obtained false papers for each of the kids, passing them along to nunneries, monasteries and to foster parents.

Elzbieta Ficowska was smuggled out in a carpenter’s toolbox at the age of six months. ‘When I was 17″, she said, “a friend said she’d heard I was Jewish. At that point, my Polish mum told me the truth, giving me a silver spoon engraved with my name and birth date, which my blood family had placed in the box with me. Elzbieta later learned that her family wept on hearing she was to be baptized, but later signaled their understanding by sending a christening gown and tiny gold cross. “I consider both my Polish mum and Irena to be a little pathological. It is a kind of insanity to overcome such fear. They were so alike, my mum and Irena – fantastic, strong women”.

Sendler was caught by the Gestapo in 1943, betrayed by a colleague under torture, and by a nosy landlady. Nazi interrogators beat her savagely, but she never gave up any of those names.

Irena lasted 100 days in Pawiak prison, a place where average inmate survival was less than a month. Finally she was returned to the Gestapo and stood against a wall for execution, too broken to care. An SS guard said “not you” and shoved her out into the street. He’d been bribed by her friends, and was himself later caught and executed. For now she was “officially” dead, which made it easier to escape detection for the remainder of the war.

After the war, Irena tried to reunite parents or surviving family members with the children she’d rescued. She was rarely successful.

All told, Irena Sendler saved about 2,400 Jewish children and infants and about 100 teenagers, who went into the forests to join partisan bands fighting the Nazis. The far better known Oskar Schindler is credited with saving less than half that number.

Today, Elzbieta Ficowska tries to keep her Jewish roots, but they seem foreign to her. ‘When I enter a Catholic church, everything is mine. Sometimes I look in the mirror for traces of my real parents. I sent letters all around the world to try to find out about them.’ She has never seen so much as a photograph.

The Polish Government honored Irena Sendler with the Order of the White Eagle, its highest award. The Yad Vashem Remembrance Center in Jerusalem honored her as a “Righteous Gentile” in 1965. She received honorary citizenship in Israel in 1985, and the Polish and Israeli Governments nominated her for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007.

The Nobel Prize for Peace was awarded on October 12 in Oslo, Norway, to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and Albert Arnold Gore Jr. “for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change”.

The Nobel Prize for Peace was awarded on October 12 in Oslo, Norway, to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and Albert Arnold Gore Jr. “for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change”.

Irena Sendler passed away on May 12, 2008 at the age of 98. This choice of 2007 Nobel prize recipients has been controversial, since Nobel by-laws prohibit posthumous award of the prize. Many felt that Sendler had more than earned it. Some have claimed that Nobel committee rules require qualifying work to have taken place within the two years immediately preceding nomination, but I think they’re making it up. I’ve read the Nobel statutes. You can do so yourself, HERE, if you’re so inclined I find no such requirement. Let me know if I missed it, the whole thing seems political, to me.

Irena Sendler always said that she wasn’t a hero, she only did what any normal person would do. I find in the story of this petite Polish nurse, some of the most magnificent courage of which our species is capable. If that does not make her a hero, I don’t know what would.

Hess was an early and ardent proponent of Nazi ideology. A True Believer. He was at Hitler’s side during the failed revolution of 1923, the “Beer Hall Putsch”. He served time with Hitler in prison, and helped him write his political opus “Mein Kampf” (My Struggle). Hess was appointed to Hitler’s cabinet when the National Socialist German Workers’ Party seized power in 1933, becoming Deputy Führer, #3 after Hermann Göring and Hitler himself. Hess signed many statutes into law, including the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, depriving the Jews of Germany of their rights and property.

Hess was an early and ardent proponent of Nazi ideology. A True Believer. He was at Hitler’s side during the failed revolution of 1923, the “Beer Hall Putsch”. He served time with Hitler in prison, and helped him write his political opus “Mein Kampf” (My Struggle). Hess was appointed to Hitler’s cabinet when the National Socialist German Workers’ Party seized power in 1933, becoming Deputy Führer, #3 after Hermann Göring and Hitler himself. Hess signed many statutes into law, including the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, depriving the Jews of Germany of their rights and property.

Anna Jarvis believed Mother’s Day to be a time of personal celebration, a time when families would gather to love and honor their mother.

Anna Jarvis believed Mother’s Day to be a time of personal celebration, a time when families would gather to love and honor their mother.

The world’s most famous dog show was first held on May 8, 1877, and called the “First Annual NY Bench Show.” The venue was Gilmore’s Garden at the corner of Madison Avenue and 26th Street, a hall which would later be known as Madison Square Garden. Interestingly, another popular Gilmore Garden event of the era was boxing. Competitive boxing was illegal in New York in those days, so events were billed as “exhibitions” or “illustrated lectures.” I love that last one.

The world’s most famous dog show was first held on May 8, 1877, and called the “First Annual NY Bench Show.” The venue was Gilmore’s Garden at the corner of Madison Avenue and 26th Street, a hall which would later be known as Madison Square Garden. Interestingly, another popular Gilmore Garden event of the era was boxing. Competitive boxing was illegal in New York in those days, so events were billed as “exhibitions” or “illustrated lectures.” I love that last one. 1,200 dogs arrived for that first show, in an event so popular that the originally planned three days morphed into four. The Westminster Kennel Club donated all proceeds from the fourth day to the ASPCA, for the creation of a home for stray and disabled dogs. The organization remains supportive of animal charities, to this day.

1,200 dogs arrived for that first show, in an event so popular that the originally planned three days morphed into four. The Westminster Kennel Club donated all proceeds from the fourth day to the ASPCA, for the creation of a home for stray and disabled dogs. The organization remains supportive of animal charities, to this day. one in 1946. Even so, “Best in Show” was awarded fifteen minutes earlier than it had been, the year before. I wonder how many puppies were named “Tug” that year. The Westminster dog show was first televised in 1948, three years before the first nationally televised college football game.

one in 1946. Even so, “Best in Show” was awarded fifteen minutes earlier than it had been, the year before. I wonder how many puppies were named “Tug” that year. The Westminster dog show was first televised in 1948, three years before the first nationally televised college football game.

Since the late 60s, the Westminster Best in Show winner has celebrated at Sardi’s, a popular mid-town eatery in the theater district and birthplace of the Tony award. And then the Nanny State descended, pronouncing that 2012 would be their last. There shalt be no dogs dining any restaurants, not while Mayor Bloomberg is around.

Since the late 60s, the Westminster Best in Show winner has celebrated at Sardi’s, a popular mid-town eatery in the theater district and birthplace of the Tony award. And then the Nanny State descended, pronouncing that 2012 would be their last. There shalt be no dogs dining any restaurants, not while Mayor Bloomberg is around.

grounded through the landing line, the ship’s fabric covering became charged in the electrically charged atmosphere, sending a spark to the air frame and igniting a hydrogen leak. Seven million cubic feet of hydrogen ignited almost simultaneously. It was over in less than 40 seconds.

grounded through the landing line, the ship’s fabric covering became charged in the electrically charged atmosphere, sending a spark to the air frame and igniting a hydrogen leak. Seven million cubic feet of hydrogen ignited almost simultaneously. It was over in less than 40 seconds. Where a person was inside the airship, had a lot to do with their chances of survival. Mr and Mrs Hermann Doehner and their three children (Irene, 16, Walter, 10, and Werner, 8) were in the dining room, watching the landing. Mr. Doehner left before the fire broke out. Mrs. Doehner and the two boys were able to jump out, but Irene went looking for her father. Both died in the crash.

Where a person was inside the airship, had a lot to do with their chances of survival. Mr and Mrs Hermann Doehner and their three children (Irene, 16, Walter, 10, and Werner, 8) were in the dining room, watching the landing. Mr. Doehner left before the fire broke out. Mrs. Doehner and the two boys were able to jump out, but Irene went looking for her father. Both died in the crash.

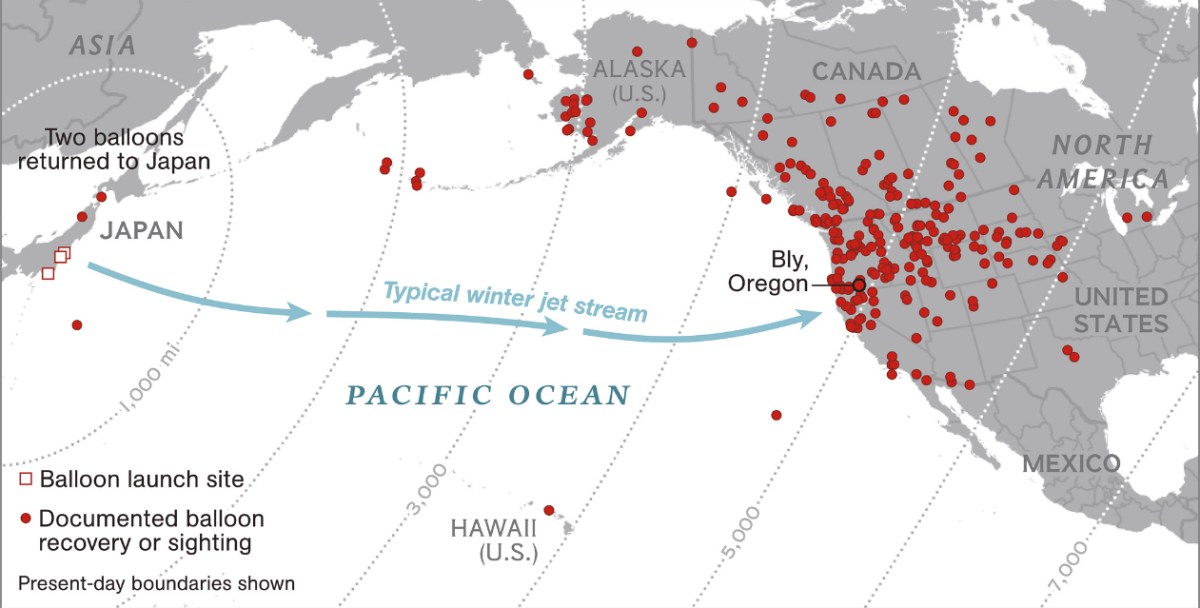

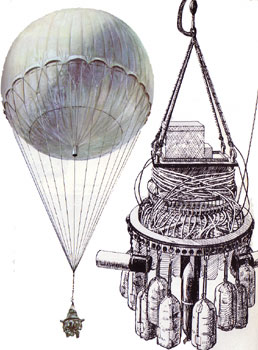

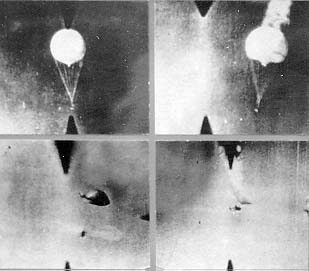

In the latter half of WWII, Imperial Japanese military thinkers conceived the fūsen bakudan or “fire balloon”, a hydrogen filled balloon device designed to ride the jet stream, using sand ballast and a valve system to navigate the weapon system onto the North American continent.

In the latter half of WWII, Imperial Japanese military thinkers conceived the fūsen bakudan or “fire balloon”, a hydrogen filled balloon device designed to ride the jet stream, using sand ballast and a valve system to navigate the weapon system onto the North American continent.

Itter Castle appeared in the land records of the Austrian Tyrol as early as 1240. When Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Schloss Itter was first leased and later requisitioned outright by the German government, for unspecified “Official use”.

Itter Castle appeared in the land records of the Austrian Tyrol as early as 1240. When Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Schloss Itter was first leased and later requisitioned outright by the German government, for unspecified “Official use”.

It was late afternoon as the convoy left for Castle Itter. Leaving Boche Buster and a few Infantry to guard the largest bridge into town. What remained of the convoy fought its way through its last SS roadblock in the early evening, roaring across the last bridge and lurching to a stop in front of Itter’s gate as night began to fall. Itter’s prisoners looked on in dismay. They had expected a column of American tanks and a heavily armed infantry force. What they had here, was a single tank with seven Americans, and a truckload of armed Germans.

It was late afternoon as the convoy left for Castle Itter. Leaving Boche Buster and a few Infantry to guard the largest bridge into town. What remained of the convoy fought its way through its last SS roadblock in the early evening, roaring across the last bridge and lurching to a stop in front of Itter’s gate as night began to fall. Itter’s prisoners looked on in dismay. They had expected a column of American tanks and a heavily armed infantry force. What they had here, was a single tank with seven Americans, and a truckload of armed Germans. concentration camp administration for the Third Reich and some of the most fanatical soldiers of WWII. Even at this late date SS units were putting up fierce resistance across northern Austria. 100-150 of them attacked on the morning of May 5. Fighting was furious around Castle Itter, the one Sherman providing machine-gun fire support until it was destroyed by a German 88mm gun. By early afternoon Lee was able to get a desperate plea for reinforcements through to the 142nd Infantry, before being cut off. Aware that he’d been unable to give complete information on the enemy’s troop strength and disposition, Lee accepted Jean Borotra’s gallant offer of assistance.

concentration camp administration for the Third Reich and some of the most fanatical soldiers of WWII. Even at this late date SS units were putting up fierce resistance across northern Austria. 100-150 of them attacked on the morning of May 5. Fighting was furious around Castle Itter, the one Sherman providing machine-gun fire support until it was destroyed by a German 88mm gun. By early afternoon Lee was able to get a desperate plea for reinforcements through to the 142nd Infantry, before being cut off. Aware that he’d been unable to give complete information on the enemy’s troop strength and disposition, Lee accepted Jean Borotra’s gallant offer of assistance. Literally vaulting over the castle wall, the tennis star ran through a gauntlet of SS strongpoints and ambushes to deliver his message, before donning an American uniform to help fight through to the castle’s defenders. The relief force arrived at around 4pm, as defenders were firing their last ammunition.

Literally vaulting over the castle wall, the tennis star ran through a gauntlet of SS strongpoints and ambushes to deliver his message, before donning an American uniform to help fight through to the castle’s defenders. The relief force arrived at around 4pm, as defenders were firing their last ammunition.

McCrae fought in one of the most horrendous battles of WWI, the second battle of Ypres, in the Flanders region of Belgium. Imperial Germany launched one of the first chemical attacks in history, attacking the Canadian position with chlorine gas on April 22, 1915. The Canadian line was broken but quickly reformed, in near-constant fighting that lasted for over two weeks.

McCrae fought in one of the most horrendous battles of WWI, the second battle of Ypres, in the Flanders region of Belgium. Imperial Germany launched one of the first chemical attacks in history, attacking the Canadian position with chlorine gas on April 22, 1915. The Canadian line was broken but quickly reformed, in near-constant fighting that lasted for over two weeks.

The vivid red flower blooming on the battlefields of Belgium, France and Gallipoli came to symbolize the staggering loss of life in that war. Since then, the red poppy has become an internationally recognized symbol of remembrance of the lives lost in all wars. I keep a red poppy pinned to my briefcase and another on the visor of my car. A reminder that no free citizen of a self-governing Republic, should ever forget where we come from. Or the prices paid by our forebears, to get us here.

The vivid red flower blooming on the battlefields of Belgium, France and Gallipoli came to symbolize the staggering loss of life in that war. Since then, the red poppy has become an internationally recognized symbol of remembrance of the lives lost in all wars. I keep a red poppy pinned to my briefcase and another on the visor of my car. A reminder that no free citizen of a self-governing Republic, should ever forget where we come from. Or the prices paid by our forebears, to get us here.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig was pitching for Columbia University against Williams College on April 18, 1923, the day that Babe Ruth hit the first home run out of the brand new Yankee Stadium. Though Columbia would lose the game, Gehrig struck out seventeen batters to set a team record.

Gehrig appeared at Yankee Stadium on “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day”, July 4, 1939. He was awarded trophies and other tokens of affection by the New York sports media, fellow players and groundskeepers. He would place each one on the ground, already too weak to hold them. Addressing his fans, Gehrig described himself as “The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth”.

Gehrig appeared at Yankee Stadium on “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day”, July 4, 1939. He was awarded trophies and other tokens of affection by the New York sports media, fellow players and groundskeepers. He would place each one on the ground, already too weak to hold them. Addressing his fans, Gehrig described himself as “The Luckiest Man on the Face of the Earth”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.