“Listen my children and you shall hear,

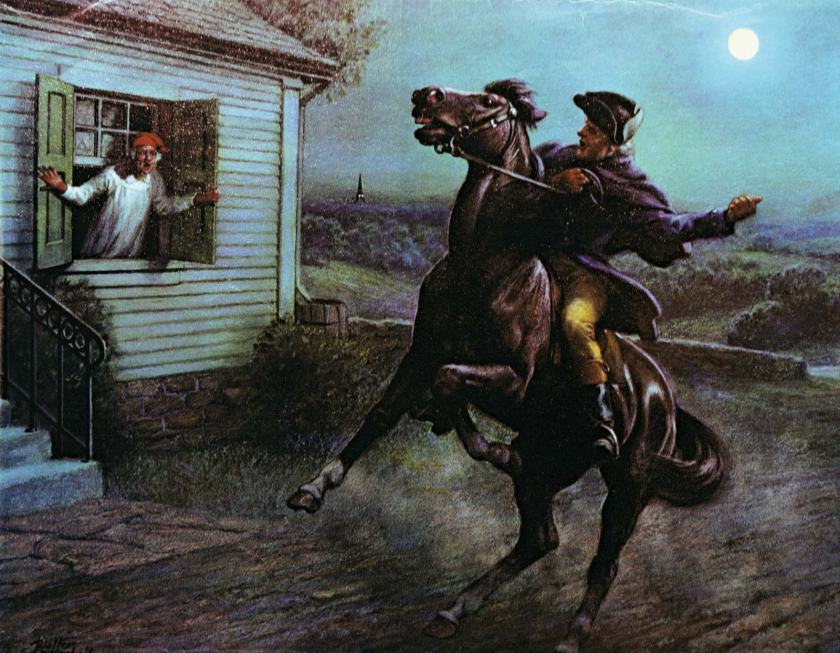

Of the midnight ride of” …Sybil Ludington.

Wait…What?

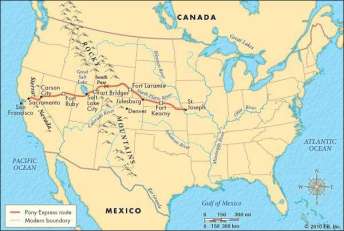

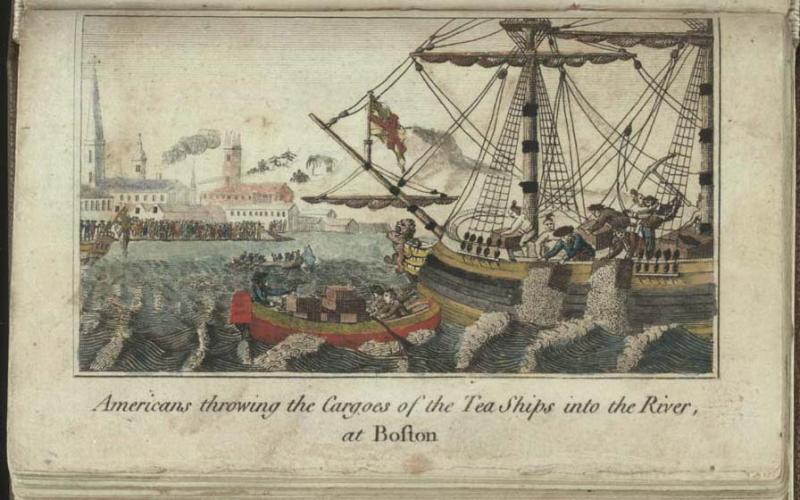

Paul Revere’s famous “midnight ride” began on the night of April 18, 1775. Revere was one of two riders, soon joined by a third, fanning out from Boston to warn of an oncoming column of “regulars”, come to destroy the stockpile of gunpowder, ammunition, and cannon located in Concord.

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

Two years later, Patriot forces maintained a similar supply depot in the southwest Connecticut town of Danbury.

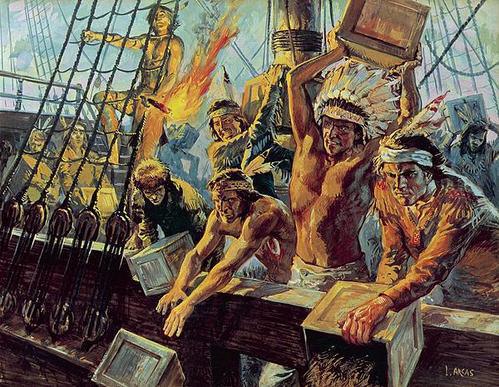

William Tryon was the Royal Governor of New York, and long-standing advocate for attacks on civilian targets. In 1777, Tryon was major-general of the provincial army. On April 25th, the General set sail for the Connecticut coast of Long Island Sound with a force of some 1,800, intending to destroy the small town.

Patriot Colonel Joseph Cooke’s small Danbury garrison was caught and quickly overpowered on the 26th, while attempting to remove food supplies, uniforms, and equipment. Facing little if any opposition, Tryon’s forces went on a bender, burning homes, farms, and storehouses. Thousands of barrels of pork, beef, and flour were destroyed, along with 5,000 pairs of shoes, 2,000 bushels of grain, and 1,600 tents.

Colonel Henry Ludington was a farmer and father of 12, with a long military career. A long-standing and loyal subject of the British crown, Ludington switched sides in 1773, joining the rebel cause and rising to command the 7th Regiment of the Dutchess County Militia, in New York’s Hudson Valley.

In April 1777, Ludington’s militia was disbanded for planting season, and spread across the countryside. An exhausted rider arrived at the Ludington farm on a blown horse on the evening of the 26th, asking for help. 15 miles away, British regulars and a force of loyalists were burning Danbury to the ground.

The Dutchess County Militia had to be called up. The Colonel had one night to prepare for battle, and this rider was done. The job would have to go to Colonel Ludington’s first-born, his daughter, Sybil.

Born April 5, 1761, Sybil Ludington was barely sixteen at the time of her ride. From Poughkeepsie to what is now Putnam County and back, the “Female Paul Revere” rode across the lower Hudson River Valley, covering 40 miles in the pitch dark of night, alerting her father’s militia to the danger and urging they come out for a fight. She’d use a stick to knock on doors, even using it once to fight off a highway bandit.

By the time Sybil returned the next morning, cold, rain-soaked, and exhausted, most of 400 militia were ready to march.

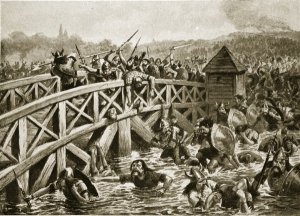

Arnold’s forces arrived too late to save Danbury, but inflicted a nasty surprise on the British rearguard as the column approached nearby Ridgefield. Never outnumbered by less than three-to-one, Connecticut militia was able to slow the British advance until Ludington’s New York Militia arrived on the following day. The last phase of the action saw the same type of swarming harassment as seen on the British retreat from Concord to Boston, early in the war. 35 miles to the east of Danbury, General Benedict Arnold was gathering a force of 500 regular and irregular Connecticut militia, with Generals David Wooster and Gold Selleck Silliman.

While the British operation was a tactical success, the mauling inflicted by these colonials ensured that this was the last hostile British landing on the Connecticut coast.

The British raid on Danbury destroyed at least 19 houses and 22 stores and barns. Town officials submitted £16,000 in claims to Congress, for which town selectmen received £500 reimbursement. Further claims were made to the General Assembly of Connecticut in 1787, for which Danbury was awarded land. In Ohio.

At the time, Benedict Arnold planned to travel to Philadelphia, to protest the promotion of officers junior to himself, to Major General. Arnold, who’d had two horses shot out from under him at Ridgefield, was promoted to Major General in recognition for his role in the battle. Along with that promotion came a horse, “properly caparisoned as a token of … approbation of his gallant conduct … in the late enterprize to Danbury.” For now, the pride which would one day be his undoing, was assuaged.The Keeler Tavern in Ridgefield is now a museum. The British cannonball fired into the side of the building, remains there to this day.

Henry Ludington would become Aide-de-Camp to General George Washington, and grandfather to Harrison Ludington, mayor of Milwaukee and 12th Governor of Wisconsin.

Gold Silliman was kidnapped with his son by a first marriage by Tory neighbors, and held for Nearly seven months at a New York farmhouse. Having no hostage of equal rank with whom to exchange for the General, Patriot forces went out and kidnapped one of their own, in the person of Chief Justice Judge Thomas Jones, of Long Island.

Mary Silliman was left to run the farm, including caring for her own midwife, who was brutally raped by English forces for denying them the use of her home. The 1993 made-for-TV movie “Mary Silliman’s War” tells the story of non-combatants, pregnant mothers and farm wives during the Revolution, as well as Mary’s own negotiations for her husband’s release from Loyalist captors.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

Sybil Ludington received the thanks of family and friends including that of George Washington, himself. And then it was as if she had stepped off the pages of history.

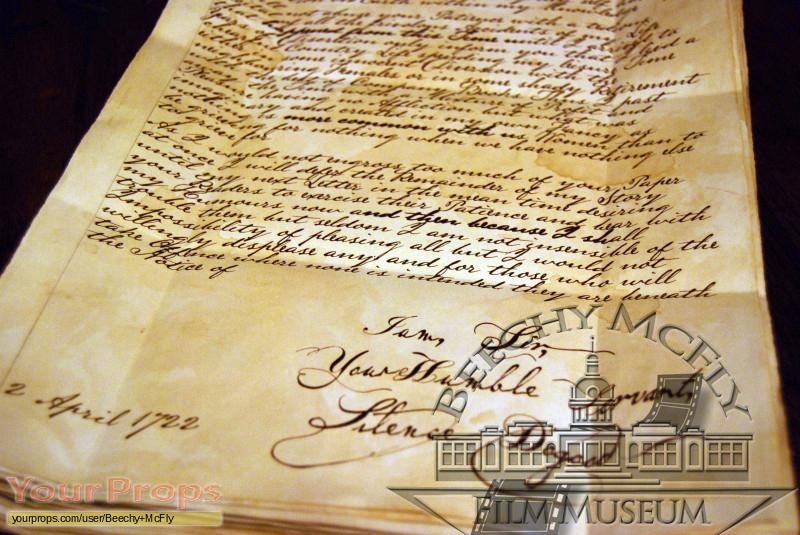

Paul Revere’s famous ride would have likewise faded into obscurity, but for the poetry of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Eighty-six years, later.

“Listen my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive…..

The United States was grossly unprepared to fight a World War in 1942. The latest iteration of “War Plan Orange” (WPO-3) called for delaying tactics in the event of war with Japan, buying time to gather US Naval assets to sail for the Philippines. The problem was, there was no fleet to gather. The flower of American pacific power in the pacific, lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Allied war planners turned their attention to defeating Adolf Hitler.

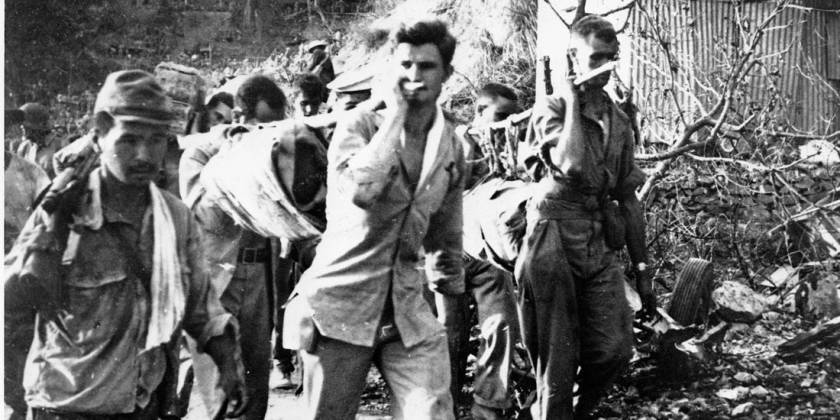

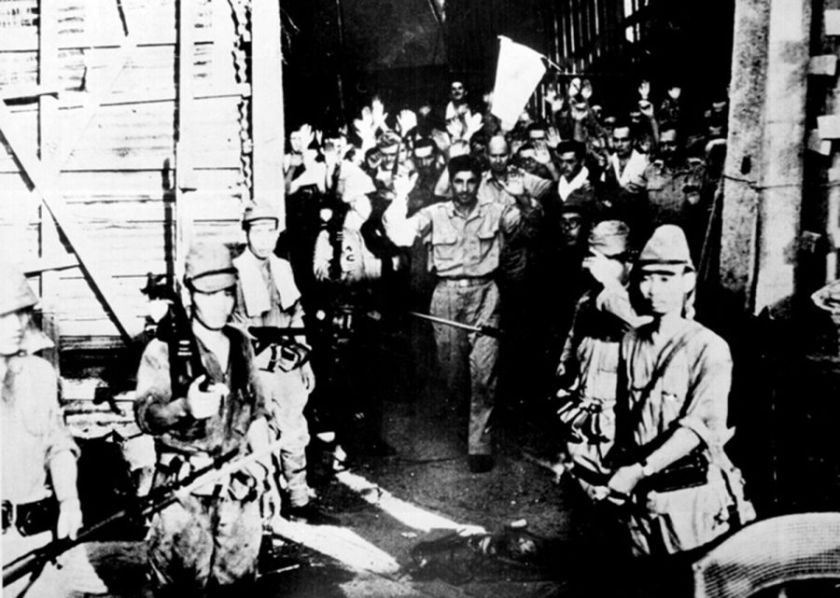

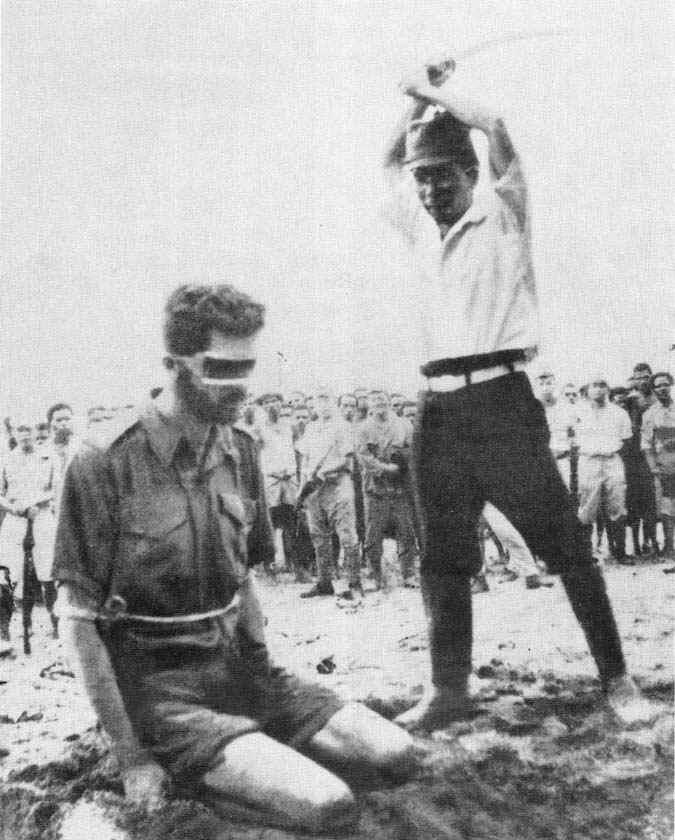

The United States was grossly unprepared to fight a World War in 1942. The latest iteration of “War Plan Orange” (WPO-3) called for delaying tactics in the event of war with Japan, buying time to gather US Naval assets to sail for the Philippines. The problem was, there was no fleet to gather. The flower of American pacific power in the pacific, lay at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. Allied war planners turned their attention to defeating Adolf Hitler. The Japanese were sadistic. Guards would beat marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Tormented by a thirst few among us can even imagine, men were made to stand for hours under a relentless sun, standing by a stream from which none were permitted to drink. The man who broke ranks and dove for the water was clubbed or bayoneted to death, on the spot. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive, others buried alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, wanton killing and savage abuse took the lives of some 500 – 650 Americans and between 5,000 – 18,000 Filipinos.

The Japanese were sadistic. Guards would beat marchers and bayonet those too weak to walk. Tormented by a thirst few among us can even imagine, men were made to stand for hours under a relentless sun, standing by a stream from which none were permitted to drink. The man who broke ranks and dove for the water was clubbed or bayoneted to death, on the spot. Japanese tanks would swerve out of their way to run over anyone who had fallen and was too slow in getting up. Some were burned alive, others buried alive. Already crippled from tropical disease and starving from the long siege of Luzon, wanton killing and savage abuse took the lives of some 500 – 650 Americans and between 5,000 – 18,000 Filipinos.  United States Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Austin Shofner came ashore back in November, with the 4th Marines. Shofner and his fellow leathernecks engaged the Japanese as early as December 12 and received their first taste of aerial bombardment, on December 29. Promoted to Captain and placed in command of Headquarters Company, Shofner received two Silver Stars by April 15 in near-constant defense against aerial attack.

United States Marine Corps 1st Lieutenant Austin Shofner came ashore back in November, with the 4th Marines. Shofner and his fellow leathernecks engaged the Japanese as early as December 12 and received their first taste of aerial bombardment, on December 29. Promoted to Captain and placed in command of Headquarters Company, Shofner received two Silver Stars by April 15 in near-constant defense against aerial attack.

Nearly 150,000 Allied soldiers were taken captive by the Japanese Empire during World War 2. Clad in unspeakably filthy rags they were fed a mere 600 calories per day of fouled rice, supplemented only by the occasional insect or bird or rodent unlucky enough to fall into desperate hands. Diseases like malaria were all but universal as gross malnutrition led to loss of vision and unrelenting nerve pain. Dysentery, a hideously infectious disease of the large intestine reduced grown men to animated skeletons. Mere scratches resulted in grotesque tropical ulcers up to a foot in length exposing living bone and rotting flesh to swarms of ravenous insects.

Nearly 150,000 Allied soldiers were taken captive by the Japanese Empire during World War 2. Clad in unspeakably filthy rags they were fed a mere 600 calories per day of fouled rice, supplemented only by the occasional insect or bird or rodent unlucky enough to fall into desperate hands. Diseases like malaria were all but universal as gross malnutrition led to loss of vision and unrelenting nerve pain. Dysentery, a hideously infectious disease of the large intestine reduced grown men to animated skeletons. Mere scratches resulted in grotesque tropical ulcers up to a foot in length exposing living bone and rotting flesh to swarms of ravenous insects. Given such cruel conditions it’s a wonder anyone escaped at all but it did happen. One time.

Given such cruel conditions it’s a wonder anyone escaped at all but it did happen. One time.

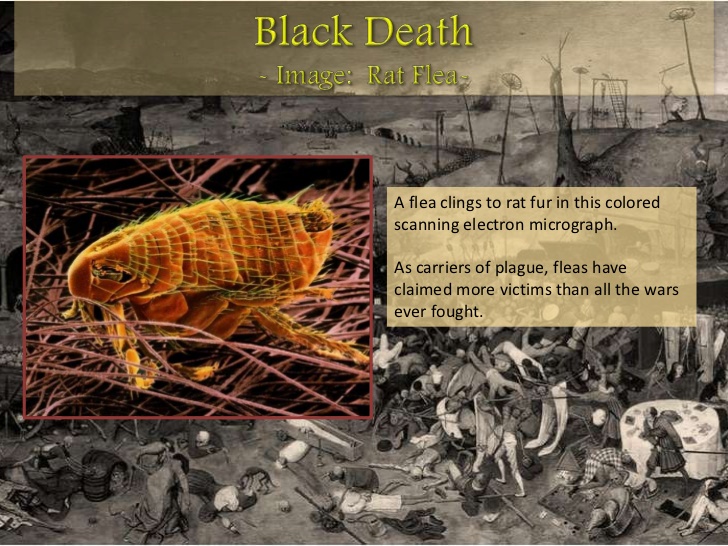

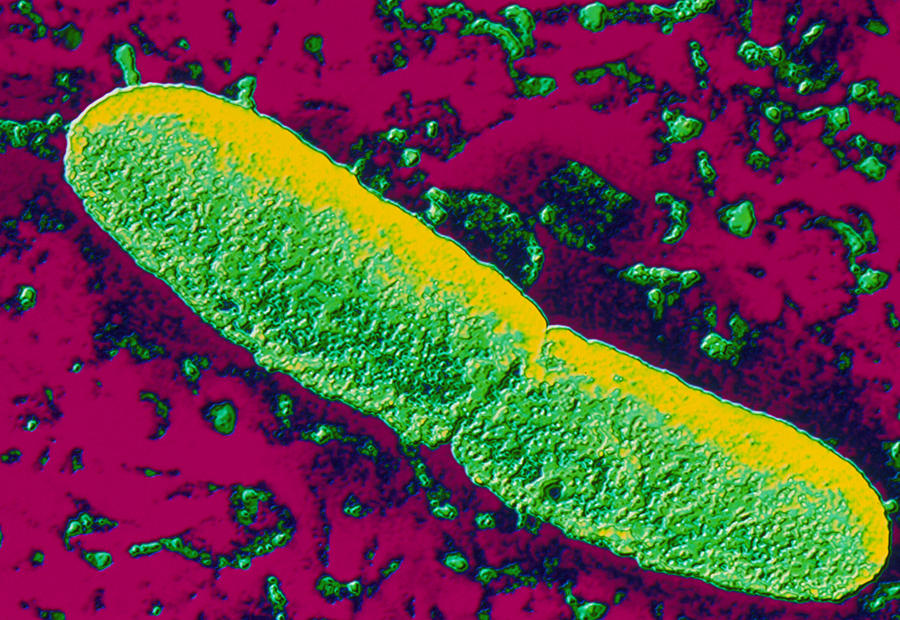

In the early 1330s, a deadly plague broke out on the steppes of Mongolia. The gram-negative bacterium Yersinia Pestis preyed heavily on rodents, the fleas from which would transmit the disease to people, the infection then rapidly spreading to others.

In the early 1330s, a deadly plague broke out on the steppes of Mongolia. The gram-negative bacterium Yersinia Pestis preyed heavily on rodents, the fleas from which would transmit the disease to people, the infection then rapidly spreading to others.

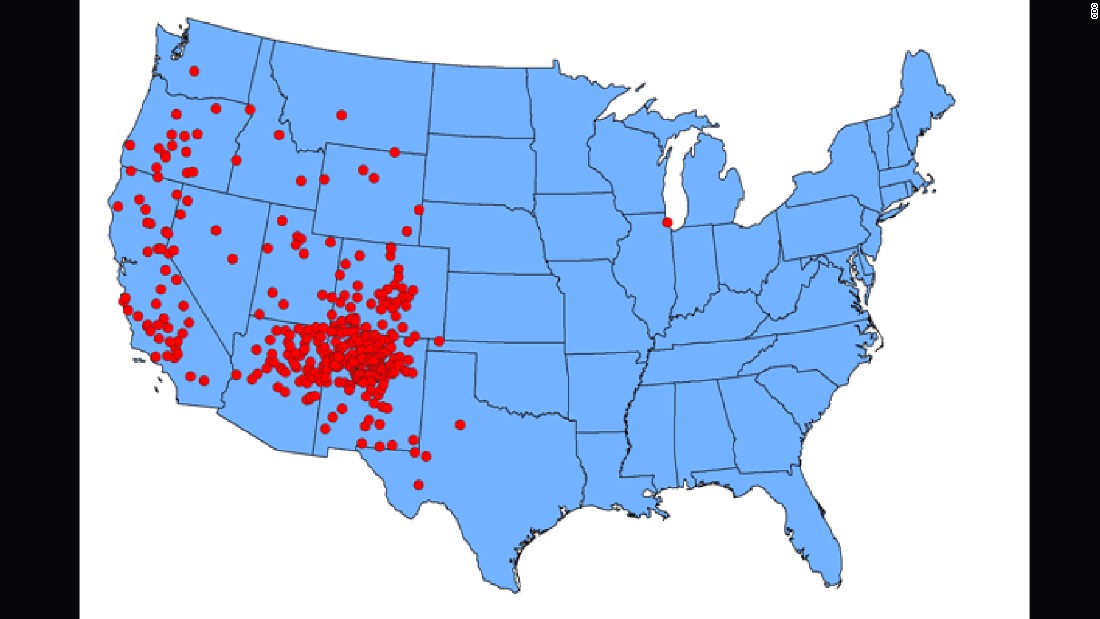

The Black death of 1346-’53 was a catastrophe unparalleled in human history, but it was by no means the last such outbreak. The Third Pandemic began in China in 1855, spreading to Hong Kong and on to British India. In China and India alone the disease killed 12 million people. It then spread to parts of Africa, Europe, Australia, and South America.

The Black death of 1346-’53 was a catastrophe unparalleled in human history, but it was by no means the last such outbreak. The Third Pandemic began in China in 1855, spreading to Hong Kong and on to British India. In China and India alone the disease killed 12 million people. It then spread to parts of Africa, Europe, Australia, and South America.

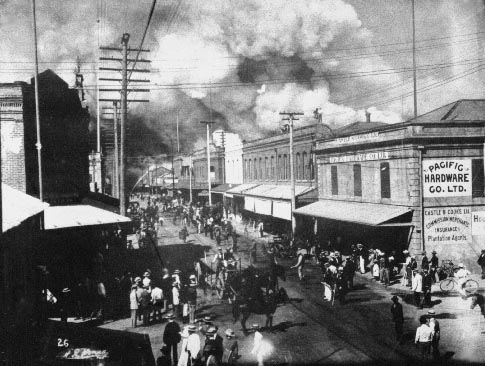

The body of an elderly Chinese man was discovered in a Chinatown basement. An autopsy found the man to have died of plague. There were more than 18,000 Chinese and another 2,000 Japanese living in the 14-block Chinatown section of the city. Many called for a quarantine of Chinatown, but Chinese citizens objected, as did then-Governor Henry Gage, who tried to sweep the whole outbreak under the carpet. Business interests likewise objected to the quarantine. Except for the Hearst Newspapers, not much was heard about it.

The body of an elderly Chinese man was discovered in a Chinatown basement. An autopsy found the man to have died of plague. There were more than 18,000 Chinese and another 2,000 Japanese living in the 14-block Chinatown section of the city. Many called for a quarantine of Chinatown, but Chinese citizens objected, as did then-Governor Henry Gage, who tried to sweep the whole outbreak under the carpet. Business interests likewise objected to the quarantine. Except for the Hearst Newspapers, not much was heard about it. San Francisco was hit by a massive earthquake on April 18, 1906, followed by a great fire. Thousands of San Franciscans were crowded into refugee camps with an even higher number of rats. For the first time, the disease now jumped the boundaries of Chinatown.

San Francisco was hit by a massive earthquake on April 18, 1906, followed by a great fire. Thousands of San Franciscans were crowded into refugee camps with an even higher number of rats. For the first time, the disease now jumped the boundaries of Chinatown.

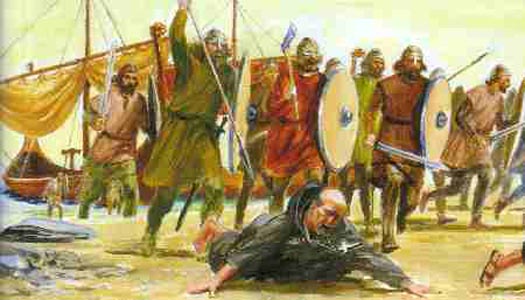

Any question you had as to their purpose would have been immediately answered, as these strangers sprinted up the beach and chased down everyone in sight. These they murdered with axe or spear, or dragged them down to the ocean and drowned them. Most of the island’s inhabitants were dead when it was over, or taken off to the ships to be sold into slavery. All of those precious objects were bagged, and tossed into the boats.

Any question you had as to their purpose would have been immediately answered, as these strangers sprinted up the beach and chased down everyone in sight. These they murdered with axe or spear, or dragged them down to the ocean and drowned them. Most of the island’s inhabitants were dead when it was over, or taken off to the ships to be sold into slavery. All of those precious objects were bagged, and tossed into the boats.

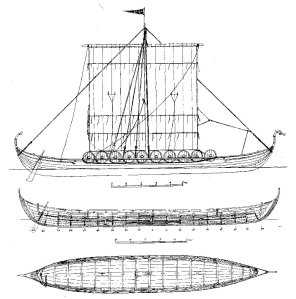

Viking travel was not all done with murderous intent; they are well known for colonizing westward as they farmed Iceland and possibly North America.

Viking travel was not all done with murderous intent; they are well known for colonizing westward as they farmed Iceland and possibly North America.

Fenians invaded Canada no fewer than five times between 1866 and 1871. The idea was to bring pressure on Britain to withdraw from Ireland, so these attacks were directed toward British army forts, customs posts and other targets in Canada.

Fenians invaded Canada no fewer than five times between 1866 and 1871. The idea was to bring pressure on Britain to withdraw from Ireland, so these attacks were directed toward British army forts, customs posts and other targets in Canada.

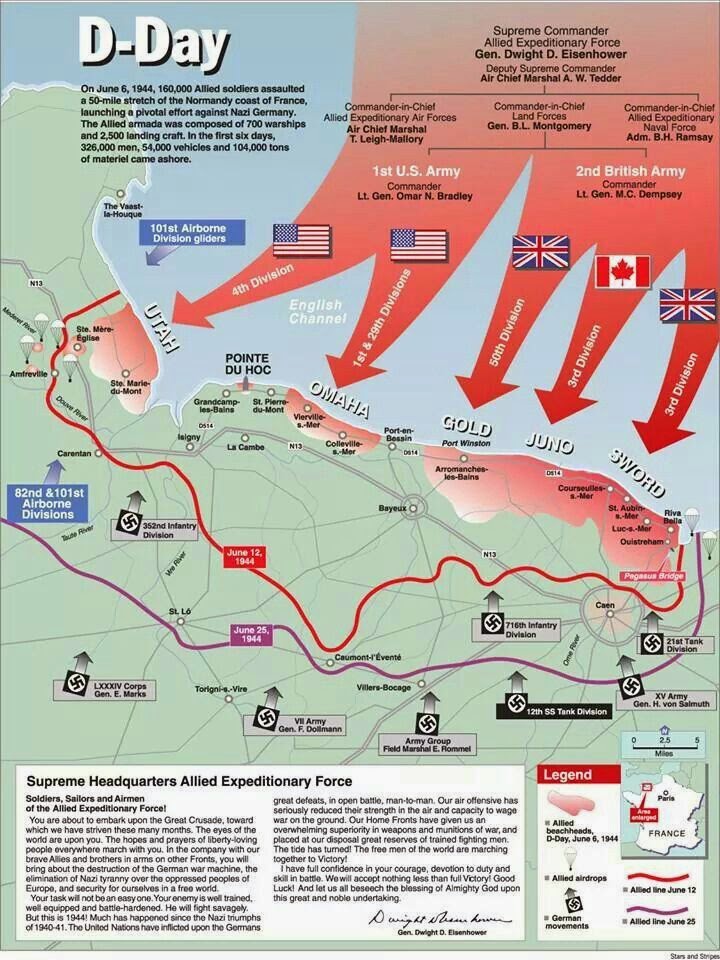

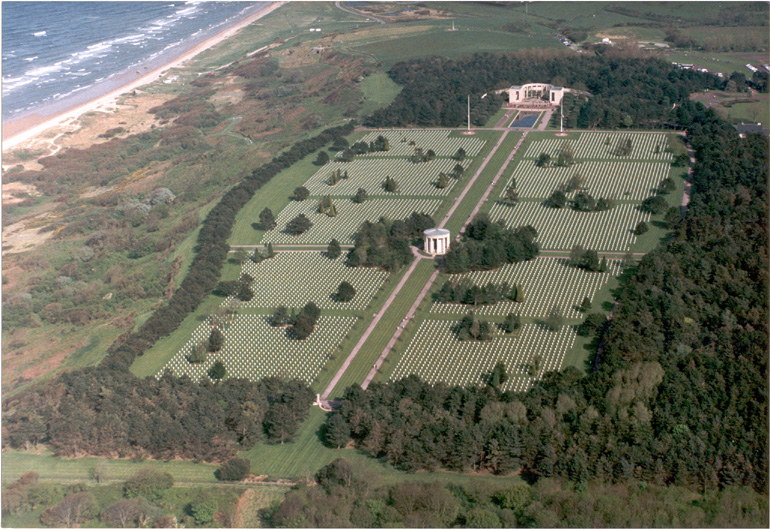

It was impossible to assemble the pieces of such a massive undertaking in secret, so an elaborate ruse called “Operation Fortitude” was launched to divert attention from the real objective. Fake field armies were assembled in Edinburgh, Scotland and the south coast of England, threatening attack on the coasts of Norway and the Pas de Calais. The real General George S. Patton was put in charge of the fake First US Army Group (FUSAG). The allied “Twenty Committee”, represented by its roman numerals “XX”, controlled a network of double agents, making the deception so complete that Hitler personally withheld critical reinforcements until long after they would have made a difference. It’s where we get the term “Double Cross”.

It was impossible to assemble the pieces of such a massive undertaking in secret, so an elaborate ruse called “Operation Fortitude” was launched to divert attention from the real objective. Fake field armies were assembled in Edinburgh, Scotland and the south coast of England, threatening attack on the coasts of Norway and the Pas de Calais. The real General George S. Patton was put in charge of the fake First US Army Group (FUSAG). The allied “Twenty Committee”, represented by its roman numerals “XX”, controlled a network of double agents, making the deception so complete that Hitler personally withheld critical reinforcements until long after they would have made a difference. It’s where we get the term “Double Cross”.

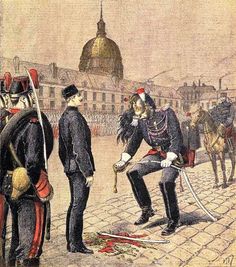

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus, but the public outcry became furious after writer Émile Zola published his vehement open letter “J’accuse” (I accuse) in the Paris press in January 1898.

Most of the political and military establishment lined up against Dreyfus, but the public outcry became furious after writer Émile Zola published his vehement open letter “J’accuse” (I accuse) in the Paris press in January 1898.

You must be logged in to post a comment.