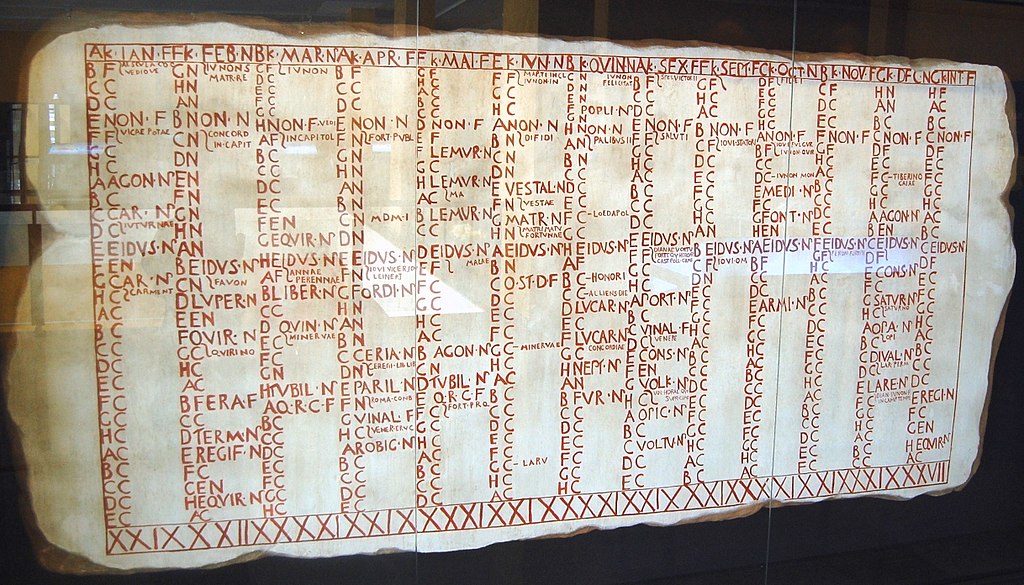

From the 7th century BC onward, the Roman calendar attempted to follow the cycles of the moon. The method often fell out of phase with the change of seasons, requiring the random addition of days. The Pontifices, the body charged with overseeing the calendar, made matters worse. Days were added to extend political terms, and to interfere with elections. Military campaigns were won or lost due to confusion over dates. By the time of Julius Caesar, things needed to change.

When Caesar went to Egypt in 48BC, he was impressed with the way the Egyptians handled the calendar. The Roman statesman hired the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes to help straighten things out. The astronomer calculated a proper year to be 365¼ days, more accurately tracking the solar and not the lunar year.

“Walk like an Egyptian” he may have said.

The new “Julian” calendar went into effect in 46BC. Caesar decreed that 67 days be added that year, moving the New Year’s start from March to January 1.

Rank hath its privileges.

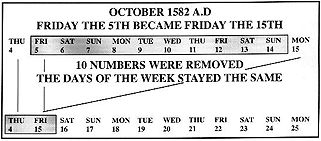

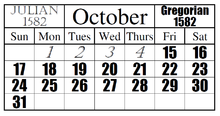

This “Julian” calendar miscalculated the solar year by 11 minutes every year, resulting in a built-in error of 1 day for every 128 years. By the late 16th century, the seasonal equinoxes were ten days out of sync, causing a problem with the holiest days of the Roman church.

In 1579, Pope Gregory XIII commissioned the Jesuit mathematician and astronomer Christopher Clavius, to devise a new calendar to correct this “drift”. The “Gregorian” calendar was adopted on this day in 1582, omitting ten days that October and changing the manner in which “leap” years were calculated.

The Catholic countries of Europe were quick to adopt the Gregorian calendar, Portugal, Spain, pontifical states, but England and her overseas colonies continued to use the Julian calendar. Confusion reigned well into the 18th century. Legal contracts, civic calendars, and the payment of rents and taxes were all complicated by the two calendar system. Military campaigns were won or lost, due to confusion over dates. Sound familiar?

Between 1582 and 1752, many English and colonial records included both the “Old Style” and “New Style” year. The system known as “double dating” resulted in date notations such as March 19, 1602/3. Others merely changed dates. Keyword search on “George Washington’s birthday” for instance, and you’ll be informed that the father of our country was born on February 22, 1732. The man was actually born on February 11, 1731 but, no matter. Washington himself recognized the date of his birth to be February 22, 1732, following adoption of the Gregorian Calendar.

Tragically, the exploding heads of historians and genealogists alike, are lost to history.

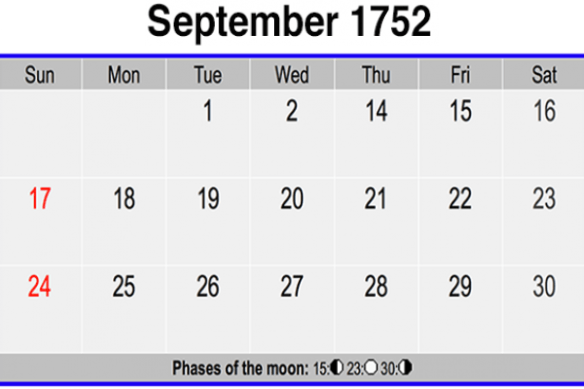

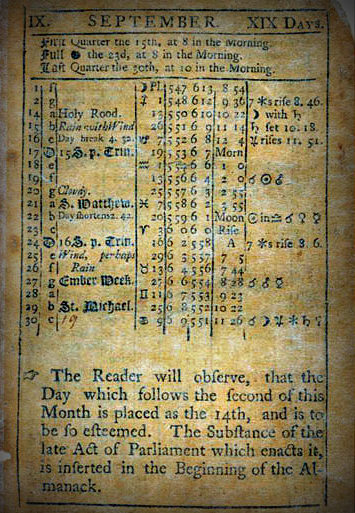

The “Calendar Act of 1750” set out a two-step process for adoption of the Gregorian calendar. Since the Roman calendar began on March 25, the year 1751 was to have only 282 days so that January 1 could be synchronized with that date. That left 11 days to deal with.

So it was decreed that Wednesday, September 2, 1782, would be followed by Thursday, September 14.

You can read about “calendar riots” around this time, though such stories may be little more than urban myth.

Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, was a prime sponsor of the calendar measure. His use of the word “Mobs” was probably a description of the bill’s opponents in Parliament. Even so, some believed their lives were being shortened by those 11 days, while others considered the new calendar to be a “Popish Plot”. The subject was very real campaign issue between Tories and Whigs in the elections of 1754.

There’s a story of one William Willett, who lived in Endon. Willett bet that he could dance non-stop for 12 days and 12 nights, starting his jig about town the evening of September 2, 1752. He stopped the next morning, and went out to collect his bets.

I am unable to determine how many actually paid up.

Ever mindful of priorities, the British tax year was officially changed in 1753, so as not to “lose” those 11 days of tax revenue. Revolution was still 23 years away in the American colonies, but the reaction “across the pond” could not have been one of unbridled joy.

The last nation to adopt the Gregorian calendar was Turkey, formally doing so in 1927.

Back in the American colonies, Ben Franklin seems to have liked the idea of those “lost days”. “It is pleasant for an old man to be able to go to bed on September 2″ he wrote, “and not have to get up until September 14.”

Much to the chagrin of Mr. Clavius, the Gregorian calendar still gets out of whack with the solar cycle by about 26 seconds, every year. Clever methods have been devised to deal with the discrepancy and several hours have already been added, but we’ll be a full day ahead by the year 4909.

I wonder how Mr. Franklin would feel to wake up and find out…it’s still yesterday.

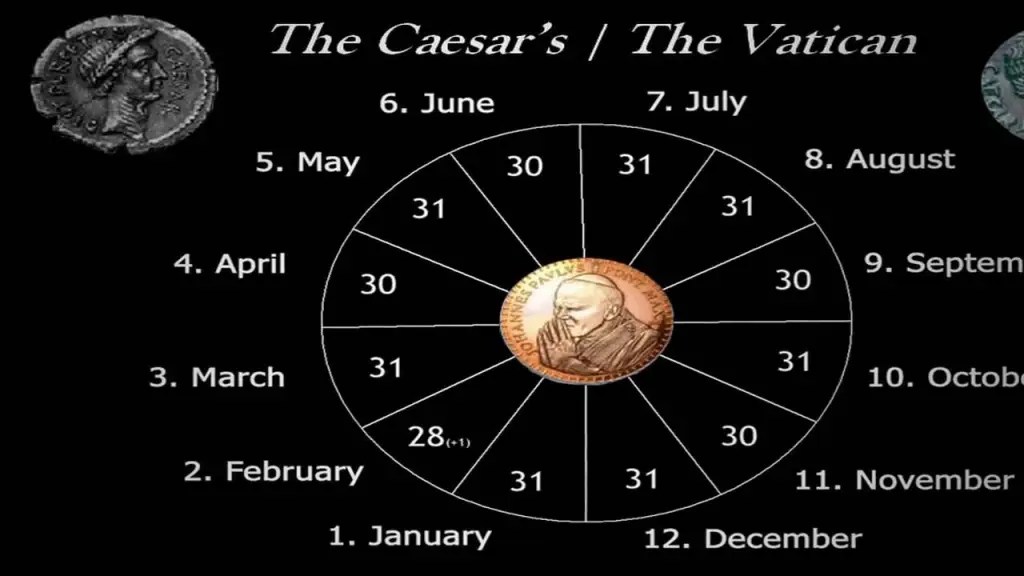

The second month had 30 days back then, when Caesar renamed his birth month from Quintilis to “Julius”, in honor of himself. Rank hath its privileges. To this day, it’s why we have “July”. Not to be outdone, Caesar’s successor Caesar Augustus changed Sextilis to Augustus and, you got it, today we have August. The only thing was, that Augustus had only 29 days to Julius’ 31, and we can’t have that.

The second month had 30 days back then, when Caesar renamed his birth month from Quintilis to “Julius”, in honor of himself. Rank hath its privileges. To this day, it’s why we have “July”. Not to be outdone, Caesar’s successor Caesar Augustus changed Sextilis to Augustus and, you got it, today we have August. The only thing was, that Augustus had only 29 days to Julius’ 31, and we can’t have that. There is an old legend that St. Bridget complained to St. Patrick back in the 5th century, that women had to wait too long for beaus to “pop the question”. Other versions of the story date back before English Law recognized the Gregorian calendar, meaning that the extra day had no legal status. Be that as it may, it is customary in many places for a woman to propose marriage on the 29th of February. According to legend, one old Scottish law of 1288 would fine the man who turned down such a proposal.

There is an old legend that St. Bridget complained to St. Patrick back in the 5th century, that women had to wait too long for beaus to “pop the question”. Other versions of the story date back before English Law recognized the Gregorian calendar, meaning that the extra day had no legal status. Be that as it may, it is customary in many places for a woman to propose marriage on the 29th of February. According to legend, one old Scottish law of 1288 would fine the man who turned down such a proposal. “With great howling and lamentation” wrote Columbus’ son Ferdinand, “they came running from every direction to the ships, laden with provisions, praying the Admiral to intercede by all means with God on their behalf; that he might not visit his wrath upon them”.

“With great howling and lamentation” wrote Columbus’ son Ferdinand, “they came running from every direction to the ships, laden with provisions, praying the Admiral to intercede by all means with God on their behalf; that he might not visit his wrath upon them”.

Sosigenes was close with his 365¼ day long year, but not quite there. The correct value of a solar year is 365.242199 days. By the year 1000, that 11-minute error had added seven days. To fix the problem, Pope Gregory XIII commissioned Jesuit astronomer Christopher Clavius to come up with yet another calendar. The Gregorian calendar was implemented in 1582, omitting ten days and adding a day on every fourth February.

Sosigenes was close with his 365¼ day long year, but not quite there. The correct value of a solar year is 365.242199 days. By the year 1000, that 11-minute error had added seven days. To fix the problem, Pope Gregory XIII commissioned Jesuit astronomer Christopher Clavius to come up with yet another calendar. The Gregorian calendar was implemented in 1582, omitting ten days and adding a day on every fourth February.

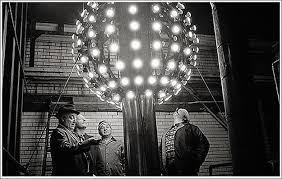

That first ball was hoist up a flagpole by five men on December 31, 1907. Once it hit the roof of the building, the ball completed an electric circuit, lighting up a sign and touching off a fireworks display.

That first ball was hoist up a flagpole by five men on December 31, 1907. Once it hit the roof of the building, the ball completed an electric circuit, lighting up a sign and touching off a fireworks display.

Benjamin Franklin seems to have liked the idea, writing that, “It is pleasant for an old man to be able to go to bed on September 2, and not have to get up until September 14.”

Benjamin Franklin seems to have liked the idea, writing that, “It is pleasant for an old man to be able to go to bed on September 2, and not have to get up until September 14.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.