Imagine for a moment, being able to see the faces of the American Revolution.

Not the paintings. Those are nothing out of the ordinary, save for the talent of the artist. I mean their photographs. Images that make it possible for you to look into their eyes.

In a letter dated May 17, 1781 and addressed to Alexander Scammell, General George Washington outlined his intention to form a light infantry unit, under Scammell’s leadership.

Comprised of Continental Line units from Connecticut, Massachusetts and New Hampshire, Milford, the Massachusetts-born Colonel’s unit was among the defensive forces which kept Sir Henry Clinton penned up in New York City, as much of the Continental army made its way south, toward a place called Yorktown.

Among the men under Scammell’s command was Henry Dearborn, future Secretary of War under President Thomas Jefferson. A teenage medic was also present. His name was Eneas Munson.

One day that medic would become Doctor Eneas Munson, professor of the Yale Medical School in New Haven Connecticut and President of the Medical Society of that state.

And a man who would live well into the age of photography.

The American Revolution ended in 1783. By the first full year of the Civil War, only 12 veterans of the Revolution remained on the pension rolls of a grateful nation.

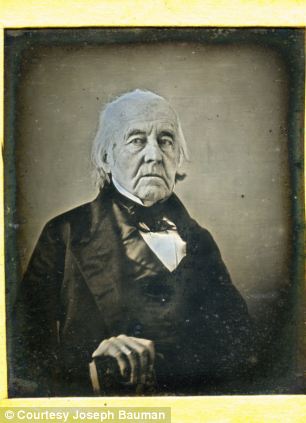

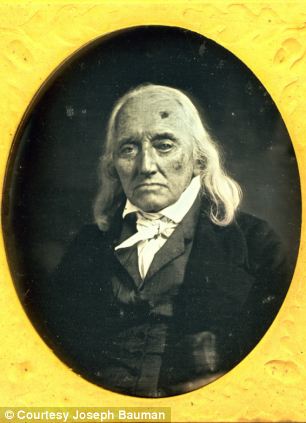

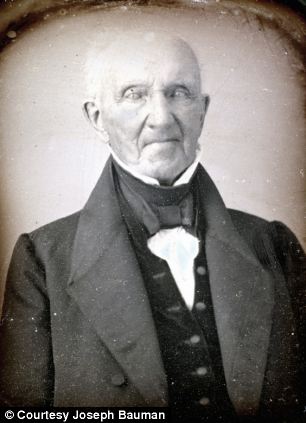

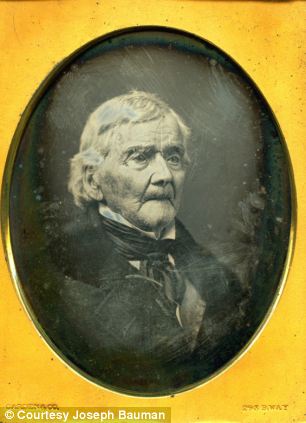

Two years later, Reverend EB Hillard brought two photographers through New York and New England to visit, and to photograph what were believed to be the last six. Each was 100 years or older at the time of the interview.

William Hutchings of York County Maine, still part of Massachusetts at the time was captured at the siege of Castine, at the age of fifteen. British authorities said it was a shame to hold one so young a prisoner, and he was released.

Reverend Daniel Waldo of Syracuse, New York fought under General Israel Putnam, becoming a POW at Horse Neck.

Adam Link of Maryland enlisted at 16 in the frontier service.

Alexander Millener of Quebec was a drummer boy in George Washington’s Life Guard.

Clarendon, New York native Lemuel Cook would live to be one of the oldest veterans of the Revolution, surviving to the age of 107. He and Alexander Millener witnessed the British surrender, at Yorktown.

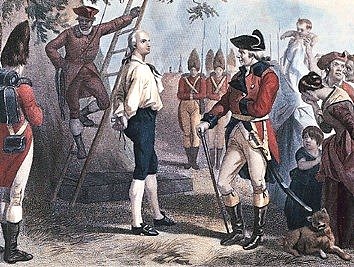

Samuel Downing from Newburyport, Massachusetts, enlisted at the age of 16 and served in the Mohawk Valley under General Benedict Arnold. “Arnold was our fighting general”, he’d say, “and a bloody fellow he was. He didn’t care for nothing, he’d ride right in. It was ‘Come on, boys!’ ’twasn’t ‘Go, boys!’ He was as brave a man as ever lived…He was a stern looking man, but kind to his soldiers. They didn’t treat him right: he ought to have had Burgoyne’s sword. But he ought to have been true. We had true men then, twasn’t as it is now”.

Hillard seems to have missed Daniel F. Bakeman, but with good reason. Bakeman had been unable to prove his service with his New York regiment. It wasn’t until 1867 that he finally received his veteran’s pension by special act of Congress.

Daniel Frederick Bakeman would become the Frank Buckles of his generation, the last surviving veteran of the Revolution. The 1874 Commissioner of Pensions report said that “With the death of Daniel Bakeman…April 5, 1869, the last of the pensioned soldiers of the Revolution passed away. He was 109.

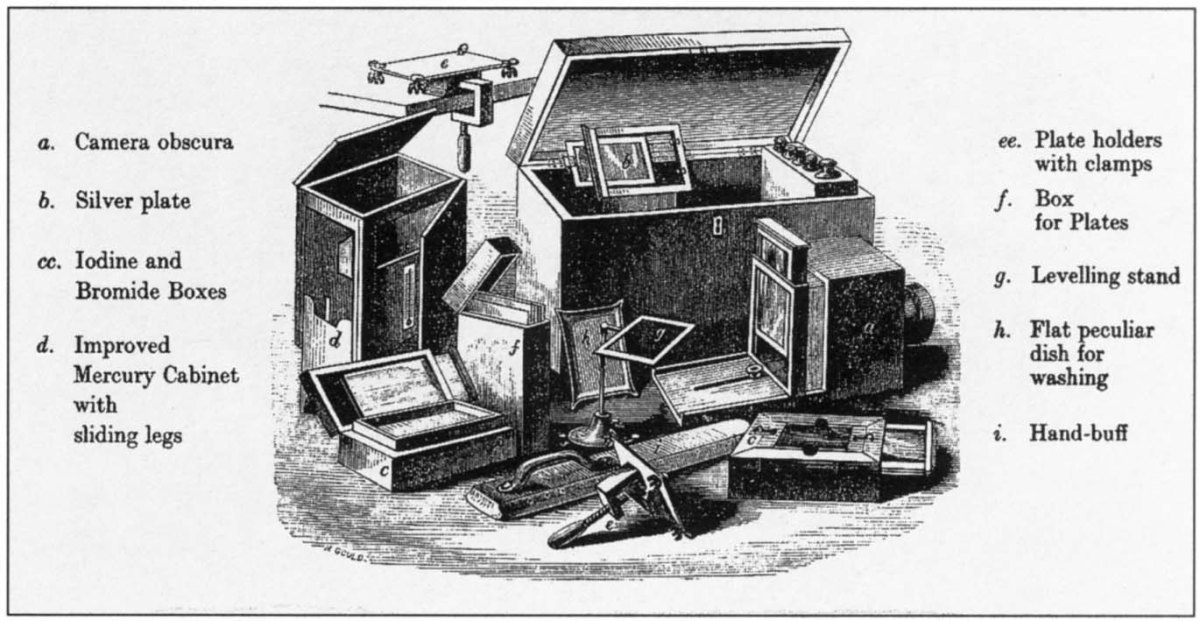

Most historians agree on 1839 as the year in which the earliest daguerreotypes were practically possible.

When Utah based investigative reporter Joe Bauman came across Hillard’s photos in 1976, he believed there must be others.

Photography had been in existence for 35 years by Reverend Hillard’s time. What followed was 30 years’ work, first finding and identifying photographs of the right vintage and then digging through muster rolls, pension files, genealogical records and a score of other source documents, to see if each was involved in the Revolution.

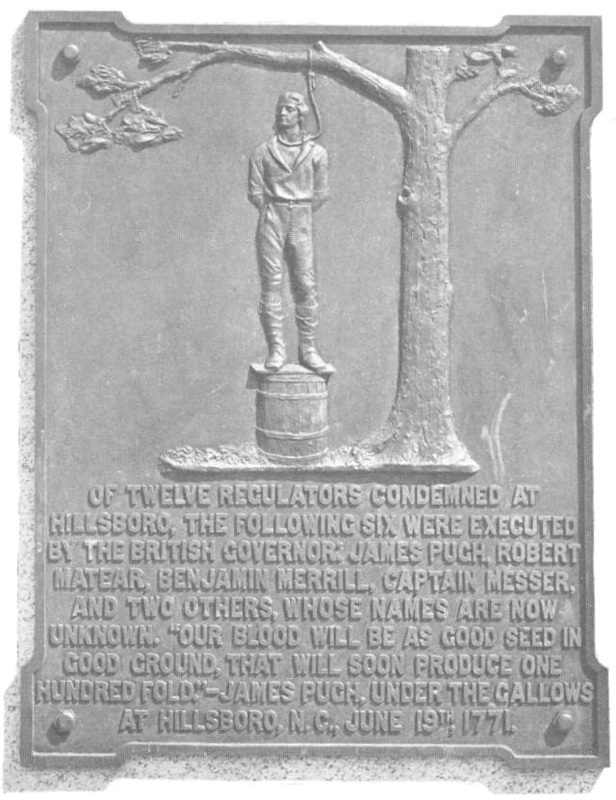

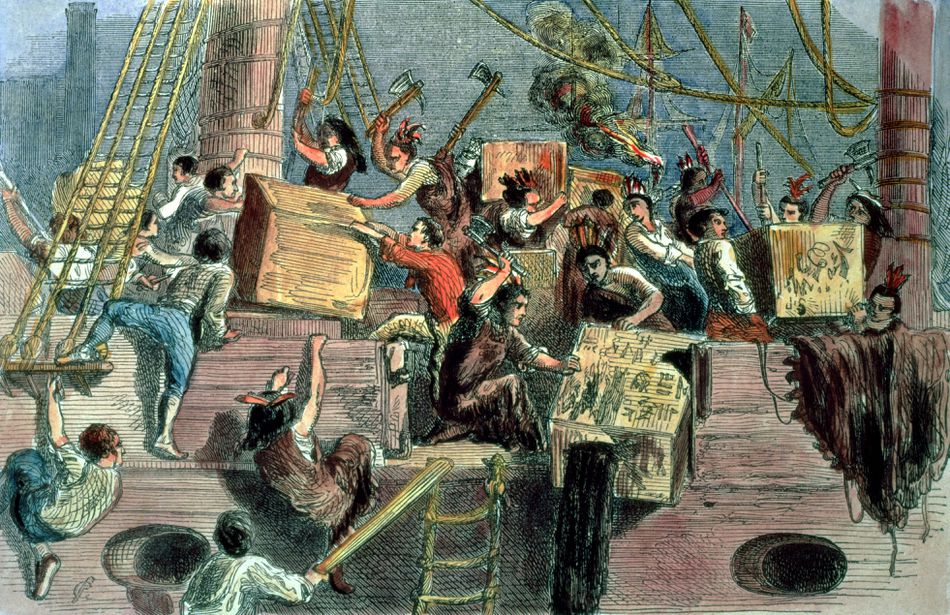

There were some, but it turned out to be a small group. Peter Mackintosh for one, was a 16-year-old blacksmith’s apprentice, from Boston. He was working the night of December 16, 1773, when a group of men ran into the shop scooping up ashes from the hearth and rubbing them on their faces. It turns out they were going to a Tea Party.

James Head was a thirteen year-old Continental Naval recruit from a remote part of what was then Massachusetts. Head would be taken prisoner but later released. He walked 224 miles from Providence to his home in what would one day be Warren, Maine.

Head was elected a Massachusetts delegate to the convention called in Boston, to ratify the Constitution. He would die the wealthiest man in Warren, stone deaf from his service in the Continental Navy.

George Fishley served in the Continental army and fought in the Battle of Monmouth, and in General John Sullivan’s campaign against British-allied Indians in New York and Pennsylvania.

Fishley would spend the rest of his days in Portsmouth New Hampshire, where he was known as ‘the last of our cocked hats.”

Daniel Spencer fought with the 2nd Continental Light Dragoons, an elite 120-man unit also known as Sheldon’s Horse after Colonel Elisha Sheldon. First mustered at Wethersfield, Connecticut, the regiment consisted of four troops from Connecticut, one troop each from Massachusetts and New Jersey, and two companies of light infantry. On August 13 1777, Sheldon’s horse put a unit of Loyalists to flight in the little-known Battle of the Flocky, the first cavalry charge in history, performed on American soil

Bauman’s research uncovered another eight in addition to Hillard’s record, including a shoemaker, two ministers, a tavern-keeper, a settler on the Ohio frontier, a blacksmith and the captain of a coastal vessel, in addition to Dr. Munson.

The experiences of these eight span the distance from the Boston Tea Party to the battles at Monmouth, Quaker Hill, Charleston and Bennington. Their eyes saw the likes of George Washington, Alexander Hamilton & Henry Knox, the battles of the Revolution and the final surrender, at Yorktown.

Bauman collected the glass plate photos of eight and paper prints of another five along with each man’s story, and published them in an ebook entitled “DON’T TREAD ON ME: Photographs and Life Stories of American Revolutionaries”.

To look into the eyes of such men is to compress time, to reach back before the age of photography, and look into the eyes of men who saw the birth of a nation.

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

Childhood memories of standing in line. Smiling. Trusting. And then…the Gun. That sound. Whack! The scream. That feeling of betrayal…being shuffled along. Next!

Childhood memories of standing in line. Smiling. Trusting. And then…the Gun. That sound. Whack! The scream. That feeling of betrayal…being shuffled along. Next!

And did you know? The American Revolution was fought out, entirely in the midst of a smallpox pandemic.

And did you know? The American Revolution was fought out, entirely in the midst of a smallpox pandemic. The idea of inoculation was not new. Terrible outbreaks occurred in Colonial Boston in 1640, 1660, 1677-1680, 1690, 1702, and 1721, killing hundreds, each time. At the time, sickness was considered the act of an angry God. Religious faith frowned on experimentation on the human body.

The idea of inoculation was not new. Terrible outbreaks occurred in Colonial Boston in 1640, 1660, 1677-1680, 1690, 1702, and 1721, killing hundreds, each time. At the time, sickness was considered the act of an angry God. Religious faith frowned on experimentation on the human body. Colonists were chary of the procedure, deeply suspicious of how deliberately infecting a healthy person, could produce a desirable outcome. John Adams submitted to the procedure in 1764 and gave the following account:

Colonists were chary of the procedure, deeply suspicious of how deliberately infecting a healthy person, could produce a desirable outcome. John Adams submitted to the procedure in 1764 and gave the following account: As Supreme Commander, General Washington had a problem. An inoculated soldier would be unfit for weeks before returning to duty. Doing nothing and hoping for the best was to invite catastrophe but so was the inoculation route, as even mildly ill soldiers were contagious and could set off a major outbreak.

As Supreme Commander, General Washington had a problem. An inoculated soldier would be unfit for weeks before returning to duty. Doing nothing and hoping for the best was to invite catastrophe but so was the inoculation route, as even mildly ill soldiers were contagious and could set off a major outbreak.

So it was on December 9, 1979, smallpox was officially described, as eradicated. The only infectious disease ever so declared.

So it was on December 9, 1979, smallpox was officially described, as eradicated. The only infectious disease ever so declared.

Burgoyne’s movements began well with the near-bloodless capture of Fort Ticonderoga in early July, 1777. By the end of July, logistical and supply problems caused Burgoyne’s forces to bog down. On July 27, a Huron-Wendat warrior allied with the British army murdered one Jane McCrae, the fiancé of a loyalist serving in Burgoyne’s army. Gone was the myth of “civilized” British conduct of the war, as dead as the dark days of late 1776 and General Washington’s “Do or Die” crossing of the Delaware and the Christmas attack on Trenton.

Burgoyne’s movements began well with the near-bloodless capture of Fort Ticonderoga in early July, 1777. By the end of July, logistical and supply problems caused Burgoyne’s forces to bog down. On July 27, a Huron-Wendat warrior allied with the British army murdered one Jane McCrae, the fiancé of a loyalist serving in Burgoyne’s army. Gone was the myth of “civilized” British conduct of the war, as dead as the dark days of late 1776 and General Washington’s “Do or Die” crossing of the Delaware and the Christmas attack on Trenton. Meanwhile, attempts to solve the supply problem culminated in the August 16 Battle of Bennington, a virtual buzz saw in which New Hampshire and Massachusetts militiamen under General John Stark along with the Vermont militia of Colonel Seth Warner and Ethan Allen’s “Green Mountain Boys”, killed or captured nearly 1,000 of Burgoyne’s men.

Meanwhile, attempts to solve the supply problem culminated in the August 16 Battle of Bennington, a virtual buzz saw in which New Hampshire and Massachusetts militiamen under General John Stark along with the Vermont militia of Colonel Seth Warner and Ethan Allen’s “Green Mountain Boys”, killed or captured nearly 1,000 of Burgoyne’s men. Meanwhile Howe’s capture of Philadelphia met with only limited success, leading to his resignation as Commander in Chief of the American station and Sir Henry Clinton, withdrawing troops to New York.

Meanwhile Howe’s capture of Philadelphia met with only limited success, leading to his resignation as Commander in Chief of the American station and Sir Henry Clinton, withdrawing troops to New York.

Fort Moultrie surrendered without a fight on May 7. Clinton demanded unconditional surrender the following day but Lincoln bargained for the “Honours of War”. Prominent citizens were by this time, asking Lincoln to surrender. On May 11, the British fired heated shot into the city, burning several homes. Benjamin Lincoln surrendered on May 12.

Fort Moultrie surrendered without a fight on May 7. Clinton demanded unconditional surrender the following day but Lincoln bargained for the “Honours of War”. Prominent citizens were by this time, asking Lincoln to surrender. On May 11, the British fired heated shot into the city, burning several homes. Benjamin Lincoln surrendered on May 12. In the summer of 1780, American General Horatio Gates suffered humiliating defeat at the Battle of Camden. Cornwallis idea of turning over one state after another to loyalists failed to materialize, as the ham-fisted brutality of officers like Banastre Tarleton, incited feelings of resentment among would-be supporters. Like the Roman general Fabius who could not defeat the Carthaginians in pitched battle, General Washington’s brilliant protege Nathaniel Greene pursued a “hit & run” strategy of “scorched earth”, attacking supply trains harassing Cornwallis’ movements at every turn.

In the summer of 1780, American General Horatio Gates suffered humiliating defeat at the Battle of Camden. Cornwallis idea of turning over one state after another to loyalists failed to materialize, as the ham-fisted brutality of officers like Banastre Tarleton, incited feelings of resentment among would-be supporters. Like the Roman general Fabius who could not defeat the Carthaginians in pitched battle, General Washington’s brilliant protege Nathaniel Greene pursued a “hit & run” strategy of “scorched earth”, attacking supply trains harassing Cornwallis’ movements at every turn. Through the Carolinas and on to Virginia, Greene’s forces pursued Cornwallis’ army. With Greene dividing his forces, General Daniel Morgan delivered a crushing defeat, defeating Tarleton’s unit at a place called Cowpens in January, 1781. The battle of Guilford Courthouse was an expensive victory, costing Cornwallis a quarter of his strength and forcing a move to the coast in hopes of resupply.

Through the Carolinas and on to Virginia, Greene’s forces pursued Cornwallis’ army. With Greene dividing his forces, General Daniel Morgan delivered a crushing defeat, defeating Tarleton’s unit at a place called Cowpens in January, 1781. The battle of Guilford Courthouse was an expensive victory, costing Cornwallis a quarter of his strength and forcing a move to the coast in hopes of resupply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.