Hannah Reitsch wanted to fly. Born March 29, 1912 into an upper-middle-class family in Hirschberg, Silesia, it’s all she ever thought about. At the age of four, she tried to jump off the family balcony, to experience flight. In her 1955 autobiography The Sky my Kingdom, Reitsch wrote: ‘The longing grew in me, grew with every bird I saw go flying across the azure summer sky, with every cloud that sailed past me on the wind, till it turned to a deep, insistent homesickness, a yearning that went with me everywhere and could never be stilled.’

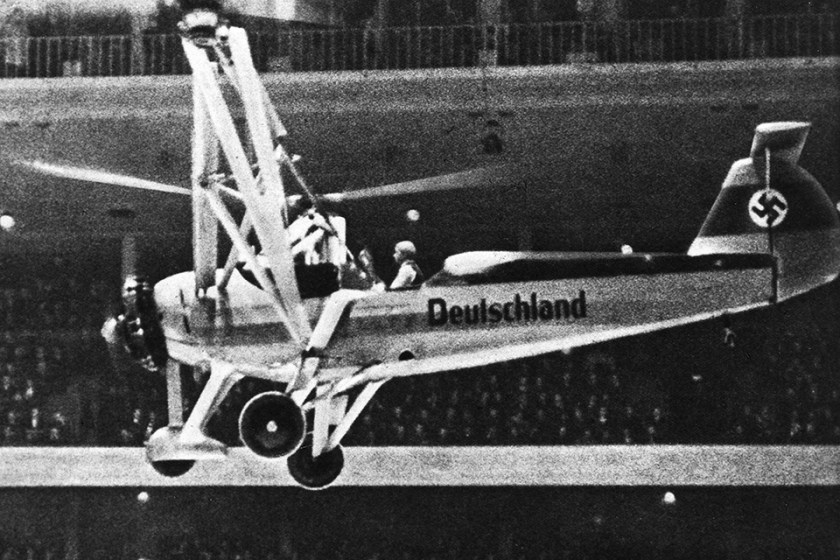

Reitsch began flying gliders in 1932, as the treaty of Versailles prohibited anyone flying “war planes” in Germany. In 1934, she broke the world’s altitude record for women (9,184 feet). In 1936, Reitsch was working on developing dive brakes for gliders, when she was awarded the honorary rank of Flugkapitän, the first woman ever so honored. In 1937 she became a Luftwaffe civilian test pilot. She would hold the position until the end of WW2.

Reitsch began flying gliders in 1932, as the treaty of Versailles prohibited anyone flying “war planes” in Germany. In 1934, she broke the world’s altitude record for women (9,184 feet). In 1936, Reitsch was working on developing dive brakes for gliders, when she was awarded the honorary rank of Flugkapitän, the first woman ever so honored. In 1937 she became a Luftwaffe civilian test pilot. She would hold the position until the end of WW2.

A German Nationalist who believed she owed her allegiance to the Fatherland more than to any party, Reitsch was patriotic and loyal, and more than a little politically naive. Her work brought her into contact with the highest levels of Nazi party officialdom. Like the victims of Soviet purges who went to their death believing that it would all stop “if only Stalin knew”, Reitsch refused to believe that Hitler had anything to do with events such as the Kristallnacht pogrom. She dismissed any talk of concentration camps, as “mere propaganda”.

As a test pilot, Reitsch won an Iron Cross, Second Class, for risking her life in an attempt to cut British barrage-balloon cables. On one test flight of the rocket powered Messerschmitt 163 Komet in 1942, she flew the thing at speeds of 500 mph, a speed nearly unheard of at the time. She spun out of control and crash-landed on her 5th flight, leaving her with severe injuries. Her nose was all but torn off, her skull fractured in four places. Two facial bones were broken, and her upper and lower jaws out of alignment. Even then, she managed to write down what had happened, before she collapsed.

Doctors did not expect her to live, let alone fly again. She spent five months in hospital, and suffered from debilitating dizzy spells. She put herself on a program of climbing trees and rooftops, to regain her sense of balance. Soon, she was test flying again.

Doctors did not expect her to live, let alone fly again. She spent five months in hospital, and suffered from debilitating dizzy spells. She put herself on a program of climbing trees and rooftops, to regain her sense of balance. Soon, she was test flying again.

On this day in 1944, Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring awarded her a special diamond-encrusted version of the Gold Medal for Military Flying. Adolf Hitler personally awarded her an Iron Cross, First Class, the first and only woman in German history, so honored.

It was while receiving this second Iron Cross in Berchtesgaden, that Reitsch suggested the creation of a Luftwaffe suicide squad, “Operation Self Sacrifice”.

Hitler was initially put off by the idea, though she finally persuaded him to look into modifying a Messerschmitt Me-328B fighter for the purpose. Reitsch put together a suicide group, becoming the first to take the pledge, though the idea would never take shape. The pledge read, in part: “I hereby voluntarily apply to be enrolled in the suicide group as a pilot of a human glider-bomb. I fully understand that employment in this capacity will entail my own death.”

Hitler was initially put off by the idea, though she finally persuaded him to look into modifying a Messerschmitt Me-328B fighter for the purpose. Reitsch put together a suicide group, becoming the first to take the pledge, though the idea would never take shape. The pledge read, in part: “I hereby voluntarily apply to be enrolled in the suicide group as a pilot of a human glider-bomb. I fully understand that employment in this capacity will entail my own death.”

The plan came to an abrupt halt when an Allied bombing raid wiped out the factory in which the prototype Me-328s were being built.

In the last days of the war, Hitler dismissed his designated successor Hermann Göring, over a telegram in which the Luftwaffe head requested permission to take control of the crumbling third Reich. Hitler appointed Generaloberst Robert Ritter von Greim, ordering Hannah to take him out of Berlin and giving each a vial of cyanide, to be used in the event of capture. The Arado Ar 96 left the improvised airstrip on the evening of April 28, under small arms fire from Soviet troops. It was the last plane to leave Berlin. Two days later, Adolf Hitler was dead.

Taken into American custody on May 9, Reitsch and von Greim repeated the same statement to American interrogators: “It was the blackest day when we could not die at our Führer’s side.” She spent 15 months in prison, giving detailed testimony as to the “complete disintegration’ of Hitler’s personality, during the last months of his life. She was found not guilty of war crimes, and released in 1946. Von Greim committed suicide, in prison.

In her 1951 memoir “Fliegen – mein leben”, (Flying is my life), Reitsch offers no moral judgement one way or the other, on Hitler or the Third Reich.

She resumed flying competitions in 1954, opening a gliding school in Ghana in 1962. She later traveled to the United States, where she met Igor Sikorsky and Neil Armstrong, and even John F. Kennedy.

Hannah Reitsch remained a controversial figure, due to her ties with the Third Reich. Shortly before her death in 1979, she responded to a description someone had written of her, as `Hitler’s girlfriend’. “I had been picked for this mission” she wrote, “because I was a pilot…I can only assume that the inventor of these accounts did not realize what the consequences would be for my life. Ever since then I have been accused of many things in connection with the Third Reich”.

Toward the end of her life, she was interviewed by the Jewish-American photo-journalist, Ron Laytner. Even then she was defiant: “And what have we now in Germany? A land of bankers and car-makers. Even our great army has gone soft. Soldiers wear beards and question orders. I am not ashamed to say I believed in National Socialism. I still wear the Iron Cross with diamonds Hitler gave me. But today in all Germany you can’t find a single person who voted Adolf Hitler into power … Many Germans feel guilty about the war. But they don’t explain the real guilt we share – that we lost“.

Toward the end of her life, she was interviewed by the Jewish-American photo-journalist, Ron Laytner. Even then she was defiant: “And what have we now in Germany? A land of bankers and car-makers. Even our great army has gone soft. Soldiers wear beards and question orders. I am not ashamed to say I believed in National Socialism. I still wear the Iron Cross with diamonds Hitler gave me. But today in all Germany you can’t find a single person who voted Adolf Hitler into power … Many Germans feel guilty about the war. But they don’t explain the real guilt we share – that we lost“.

Hannah Reitsch died in Frankfurt on August 24, 1979, of an apparent heart attack. Former British test pilot and Royal Navy officer Eric Brown received a letter from her earlier that month, in which she wrote, “It began in the bunker, there it shall end.” There was no autopsy, or at least there’s no report of one. Brown, for one, believes that after all those years, she may have finally taken that cyanide capsule.

The military and governing structure of the time was based on a rigid and inflexible class system, placing the feudal lords or daimyō at the top, followed by a warrior-caste of samurai, and a lower caste of merchants and artisans. At the bottom of it all stood some 80% of the population, the peasant farmer forbidden to engage in non-agricultural work, and expected to provide the income to make the whole system work.

The military and governing structure of the time was based on a rigid and inflexible class system, placing the feudal lords or daimyō at the top, followed by a warrior-caste of samurai, and a lower caste of merchants and artisans. At the bottom of it all stood some 80% of the population, the peasant farmer forbidden to engage in non-agricultural work, and expected to provide the income to make the whole system work. In time, these internal Japanese issues and the growing pressure of western encroachment led to the end of the Tokugawa period and the restoration of the Meiji Emperor, in 1868. The divisions would last, well into the 20th century.

In time, these internal Japanese issues and the growing pressure of western encroachment led to the end of the Tokugawa period and the restoration of the Meiji Emperor, in 1868. The divisions would last, well into the 20th century.

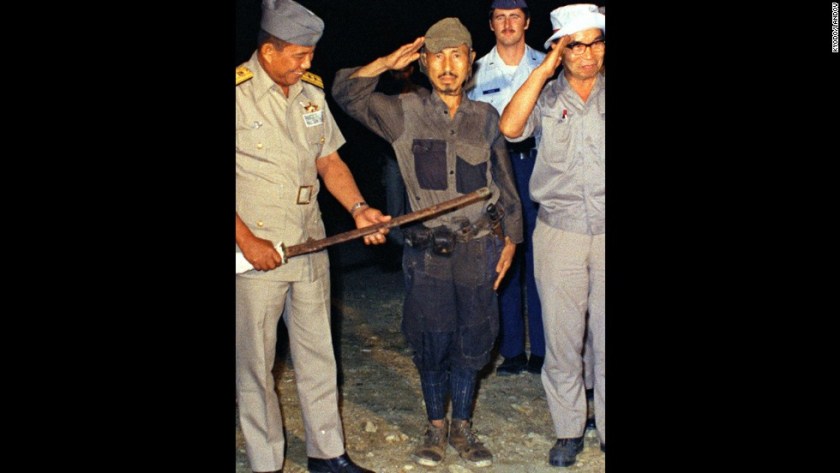

Imperial Japan would rage for another 33 years.

Imperial Japan would rage for another 33 years.

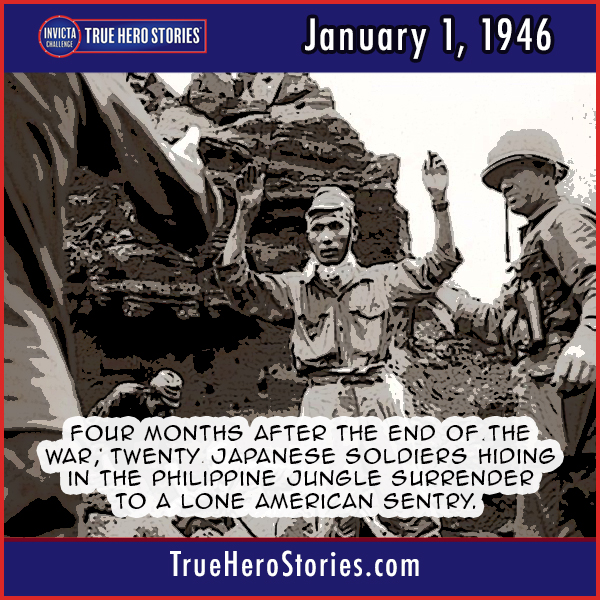

Several went on to fight for the Viet Minh against French troops in Indochina.

Several went on to fight for the Viet Minh against French troops in Indochina.

On February 7, the 71st Infantry and supporting tanks reached Ramree town where they found determined Japanese resistance, the town falling two days later. Naval forces blockaded small tributaries called “chaungs”, which the retreating Japanese used in their flight to the mainland. A Japanese air raid damaged an allied destroyer on the 11th as a flotilla of small craft crossed the strait, to rescue survivors of the garrison. By February 17, Japanese resistance had come to an end.

On February 7, the 71st Infantry and supporting tanks reached Ramree town where they found determined Japanese resistance, the town falling two days later. Naval forces blockaded small tributaries called “chaungs”, which the retreating Japanese used in their flight to the mainland. A Japanese air raid damaged an allied destroyer on the 11th as a flotilla of small craft crossed the strait, to rescue survivors of the garrison. By February 17, Japanese resistance had come to an end.

The “Battle of the Atlantic” lasted 5 years, 8 months and 5 days, ranging from the Irish Sea to the Gulf of Mexico, from the Caribbean to the Arctic Ocean. Winston Churchill would describe this as “the dominating factor all through the war. Never for a moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome”.

The “Battle of the Atlantic” lasted 5 years, 8 months and 5 days, ranging from the Irish Sea to the Gulf of Mexico, from the Caribbean to the Arctic Ocean. Winston Churchill would describe this as “the dominating factor all through the war. Never for a moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome”. New weapons and tactics would shift the balance first in favor of one side, and then to the other. In the end over 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships would be sunk to the bottom of the ocean, compared with the loss of 783 U-boats.

New weapons and tactics would shift the balance first in favor of one side, and then to the other. In the end over 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships would be sunk to the bottom of the ocean, compared with the loss of 783 U-boats.

and crews to breathe while running submerged. Venturer was on batteries when the first sounds were detected, giving the British sub the stealth advantage but sharply limiting the time frame in which it could act.

and crews to breathe while running submerged. Venturer was on batteries when the first sounds were detected, giving the British sub the stealth advantage but sharply limiting the time frame in which it could act. With four incoming at as many depths, the German sub didn’t have time to react. Wolfram was only just retrieving his snorkel and converting to electric, when the #4 torpedo struck. U-864 imploded and sank, instantly killing all 73 aboard.

With four incoming at as many depths, the German sub didn’t have time to react. Wolfram was only just retrieving his snorkel and converting to electric, when the #4 torpedo struck. U-864 imploded and sank, instantly killing all 73 aboard.

Those who could escape scrambled onto the deck, injured, disoriented, many still in their underwear as they emerged into the cold and darkness.

Those who could escape scrambled onto the deck, injured, disoriented, many still in their underwear as they emerged into the cold and darkness. Dorchester was listing hard to starboard and taking on water fast, with only 20 minutes to live. Port side lifeboats were inoperable due to the ship’s angle. Men jumped across the void into those on the starboard side, overcrowding them to the point of capsize. Only two of fourteen lifeboats launched successfully.

Dorchester was listing hard to starboard and taking on water fast, with only 20 minutes to live. Port side lifeboats were inoperable due to the ship’s angle. Men jumped across the void into those on the starboard side, overcrowding them to the point of capsize. Only two of fourteen lifeboats launched successfully. Rushing back to the scene, coast guard cutters found themselves in a sea of bobbing red lights, the water-activated emergency strobe lights of individual life jackets. Most marked the location of corpses. Of the 904 on board, the Coast Guard plucked 230 from the water, alive.

Rushing back to the scene, coast guard cutters found themselves in a sea of bobbing red lights, the water-activated emergency strobe lights of individual life jackets. Most marked the location of corpses. Of the 904 on board, the Coast Guard plucked 230 from the water, alive. John 15:13 says “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”. Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew when he gave away his only hope for survival, Father Washington did not ask for a Catholic. Neither minister Fox nor Poling asked for a Protestant. Each gave his life jacket to the nearest man.

John 15:13 says “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends”. Rabbi Goode did not call out for a Jew when he gave away his only hope for survival, Father Washington did not ask for a Catholic. Neither minister Fox nor Poling asked for a Protestant. Each gave his life jacket to the nearest man.

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik was paroled in 1942, his criminal record making him 4F. “Registrant not acceptable for military service”. He took a job at the Montella Plumbing and Heating company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he met bookkeeper Antoinette Wisniewski, the woman who would later become his wife.

Edward Donald “Eddie” Slovik was paroled in 1942, his criminal record making him 4F. “Registrant not acceptable for military service”. He took a job at the Montella Plumbing and Heating company in Dearborn, Michigan, where he met bookkeeper Antoinette Wisniewski, the woman who would later become his wife. The rapid movement of the army during this period caused difficulty for many replacements, in finding their units. Edward Slovik and John Tankey finally caught up with the 109th on October 7. The following day, Slovik asked his company commander Captain Ralph Grotte for reassignment to a rear unit, saying he was “too scared” to be part of a rifle company. Grotte refused, confirming that, were he to run away, such an act would constitute desertion.

The rapid movement of the army during this period caused difficulty for many replacements, in finding their units. Edward Slovik and John Tankey finally caught up with the 109th on October 7. The following day, Slovik asked his company commander Captain Ralph Grotte for reassignment to a rear unit, saying he was “too scared” to be part of a rifle company. Grotte refused, confirming that, were he to run away, such an act would constitute desertion. “I, Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik, 36896415, confess to the desertion of the United States Army. At the time of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”.

“I, Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik, 36896415, confess to the desertion of the United States Army. At the time of my desertion we were in Albuff [Elbeuf] in France. I came to Albuff as a replacement. They were shelling the town and we were told to dig in for the night. The following morning they were shelling us again. I was so scared, nerves and trembling, that at the time the other replacements moved out, I couldn’t move. I stayed there in my fox hole till it was quiet and I was able to move. I then walked into town. Not seeing any of our troops, so I stayed over night at a French hospital. The next morning I turned myself over to the Canadian Provost Corp. After being with them six weeks I was turned over to American M.P. They turned me loose. I told my commanding officer my story. I said that if I had to go out there again I’d run away. He said there was nothing he could do for me so I ran away again AND I’LL RUN AWAY AGAIN IF I HAVE TO GO OUT THERE. — Signed Pvt. Eddie D. Slovik A.S.N. 36896415”. 1.7 million courts-martial were held during WWII, 1/3rd of all the criminal cases tried in the United States during the same period. The death penalty was rarely imposed. When it was, it was almost always in cases of rape or murder.

1.7 million courts-martial were held during WWII, 1/3rd of all the criminal cases tried in the United States during the same period. The death penalty was rarely imposed. When it was, it was almost always in cases of rape or murder.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. A year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland the following September, London mayor Herbert Morrison was at 10 Downing Street, meeting with Chamberlain’s aide, Sir Horace Wilson. Morrison believed that the time had come for Operation Pied Piper. A year to the day from the Prime Minister’s “Peace in our Time” declaration, Wilson protested. “But we’re not at war yet, and we wouldn’t want to do anything to upset delicate negotiations, would we?”

BBC History reported that, “within a week, a quarter of the population of Britain would have a new address”.

BBC History reported that, “within a week, a quarter of the population of Britain would have a new address”. The evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly, considering. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’

The evacuation of all that humanity ran relatively smoothly, considering. James Roffey, founder of the Evacuees Reunion Association, recalls ‘We marched to Waterloo Station behind our head teacher carrying a banner with our school’s name on it. We all thought it was a holiday, but the only thing we couldn’t work out was why the women and girls were crying.’ In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.”

In the 2003 BBC Radio documentary “Evacuation: The True Story,” clinical psychologist Steve Davis described the worst cases, as “little more than a pedophile’s charter.” Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were, and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians.

Authorities produced posters urging parents to leave the kids where they were, and a good thing, too. The Blitz against London itself began on September 7. The city experienced the most devastating attack to-date on December 29, in a blanket fire-bombing that killed almost 3,600 civilians. By October 1940, the “

By October 1940, the “

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

In the end, many family ‘reunions’ were as emotionally bruising as the original breakup. Years had come and gone and new relationships had formed. The war had turned biological family members, into all but strangers.

20,000 died from sickness or hunger, or were murdered by Japanese guards on the 60 mile “death march” from Bataan, into captivity at Cabanatuan prison and others.

20,000 died from sickness or hunger, or were murdered by Japanese guards on the 60 mile “death march” from Bataan, into captivity at Cabanatuan prison and others. Two rice rations per day, fewer than 800 calories, were supplemented by the occasional animal or insect caught and killed inside camp walls, or by the rare food items smuggled in by civilian visitors.

Two rice rations per day, fewer than 800 calories, were supplemented by the occasional animal or insect caught and killed inside camp walls, or by the rare food items smuggled in by civilian visitors. On December 14, some fifty to sixty soldiers of the Japanese 14th Area Army in Palawan doused 150 prisoners with gasoline and set them on fire, machine gunning or clubbing any who tried to escape the flames. Some thirty to forty managed to escape the killing zone, only to be hunted down and murdered, one by one. Eleven managed to escape the slaughter, and lived to tell the tale. 139 were burned, clubbed or machine gunned to death.

On December 14, some fifty to sixty soldiers of the Japanese 14th Area Army in Palawan doused 150 prisoners with gasoline and set them on fire, machine gunning or clubbing any who tried to escape the flames. Some thirty to forty managed to escape the killing zone, only to be hunted down and murdered, one by one. Eleven managed to escape the slaughter, and lived to tell the tale. 139 were burned, clubbed or machine gunned to death.

He dressed and shaved, put on his best clothes, and walked out of camp. Passing guerrillas found him and passed him to a tank destroyer. Give the man points for style. A few days later, Edwin Rose strolled into 6th army headquarters, a cane tucked under his arm.

He dressed and shaved, put on his best clothes, and walked out of camp. Passing guerrillas found him and passed him to a tank destroyer. Give the man points for style. A few days later, Edwin Rose strolled into 6th army headquarters, a cane tucked under his arm.

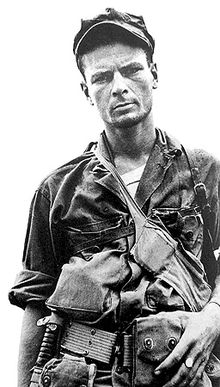

Murphy’s company commander thought he wasn’t big enough for infantry service, and attempted to transfer him to cook and bakers’ school. Murphy refused. He wanted to be a combat soldier.

Murphy’s company commander thought he wasn’t big enough for infantry service, and attempted to transfer him to cook and bakers’ school. Murphy refused. He wanted to be a combat soldier. He was still in the hospital when his unit moved into the Vosges Mountains, in Eastern France.

He was still in the hospital when his unit moved into the Vosges Mountains, in Eastern France. “Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”.

“Second Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, 01692509, 15th Infantry, Army of the United States, on 26 January 1945, near Holtzwihr, France, commanded Company B, which was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry. Lieutenant Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to a prepared position in a woods while he remained forward at his command post and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him to his right one of our tank destroyers received a direct hit and began to burn. Its crew withdrew to the woods. Lieutenant Murphy continued to direct artillery fire which killed large numbers of the advancing enemy infantry. With the enemy tanks abreast of his position, Lieutenant Murphy climbed on the burning tank destroyer which was in danger of blowing up any instant and employed its .50 caliber machine gun against the enemy. He was alone and exposed to the German fire from three sides, but his deadly fire killed dozens of Germans and caused their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back. For an hour the Germans tried every available weapon to eliminate Lieutenant Murphy, but he continued to hold his position and wiped out a squad which was trying to creep up unnoticed on his right flank. Germans reached as close as 10 yards only to be mowed down by his fire. He received a leg wound but ignored it and continued the single-handed fight until his ammunition was exhausted. He then made his way to his company, refused medical attention, and organized the company in a counterattack which forced the Germans to withdraw. His directing of artillery fire wiped out many of the enemy; he personally killed or wounded about 50. Lieutenant Murphy’s indomitable courage and his refusal to give an inch of ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective”. The man who had once been judged too small to fight was one of the most decorated American combat soldiers of WW2, having received every military combat award for valor the United States Army has to give, plus additional awards for heroism, from France and from Belgium.

The man who had once been judged too small to fight was one of the most decorated American combat soldiers of WW2, having received every military combat award for valor the United States Army has to give, plus additional awards for heroism, from France and from Belgium.

You must be logged in to post a comment.