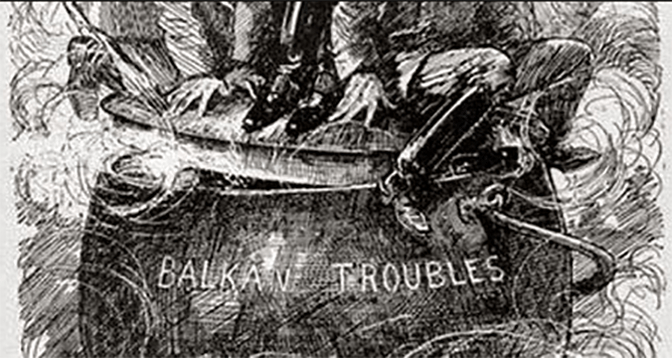

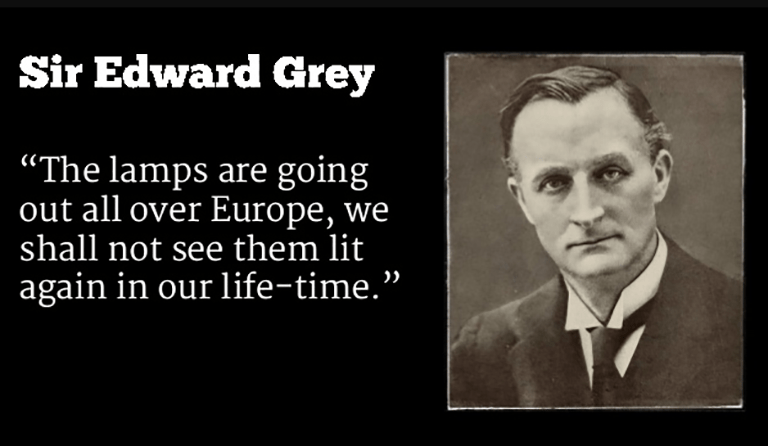

The “War to end all Wars” exploded across the European continent in the summer of 1914, devolving into the stalemate of trench warfare, by October.

The ‘Great War’ became Total War, the following year. 1915 saw the first use of asphyxiating gas, first at Bolimow in Poland, and later (and more famously) near the Belgian village of Ypres. Ottoman deportation of its Armenian minority led to the systematic extermination of an ethnic minority, resulting in the death of ¾ of an estimated 2 million Armenians living in the Empire at that time, and coining the term ‘genocide‘.

Kaiser Wilhelm responded to the Royal Navy’s near-stranglehold of surface shipping with a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, as the first zeppelin raids were carried out against the British mainland. German forces adopted a defensive strategy on the western front, developing the most sophisticated defensive capabilities of the war and determined to “bleed France white”, while concentrating on the defeat of Czarist Russia.

Russian Czar Nicholas II took personal command that September, following catastrophic losses in Galicia and Poland. Austro-German offensives resulted in 1.4 million Russian casualties by September with another 750,000 captured, spurring a “Great Retreat” of Russian forces in the east, and resulting in political and social unrest which would topple the Imperial government, fewer than two years later. In December, British and ANZAC forces broke off a meaningless stalemate on the Gallipoli peninsula, beginning the evacuation of some 83,000 survivors. The disastrous offensive had produced some 250,000 casualties. The Gallipoli campaign was remembered as a great Ottoman victory, a defining moment in Turkish history. For now, Turkish troops held their fire in the face of the allied withdrawal, happy to see them leave.

A single day’s fighting in the great battles of 1916 could produce more casualties than every European war of the preceding 100 years, civilian and military, combined. Over 16 million were killed and another 20 million wounded, while vast stretches of the Western European countryside were literally torn apart.

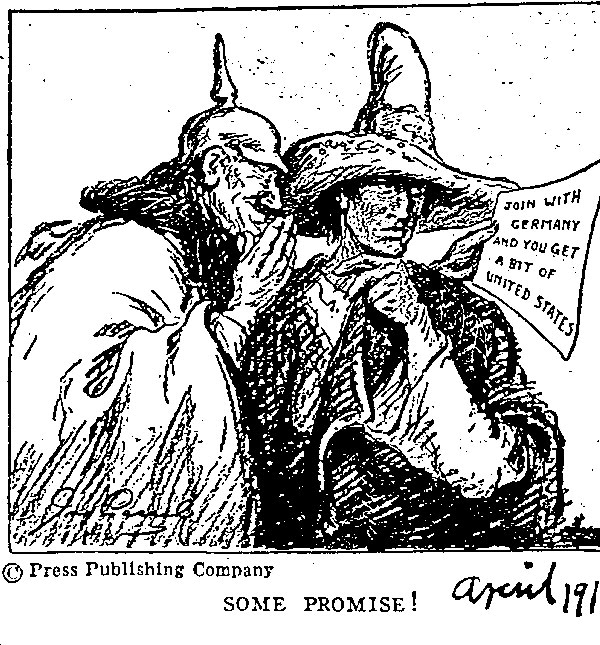

1917 saw the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, and a German invitation to bring Mexico into the war, against the United States. As expected, these policies brought America into the war on the allied side. The President who won re-election for being ‘too proud to fight’ asked for a congressional declaration of war, that April.

Massive French losses stemming from the failed Nivelle offensive of that same month (French casualties were fully ten times what was expected) combined with irrational expectations that American forces would materialize on the western front led to massive unrest in the French lines. Fully one-half of all French forces on the western front mutinied. It’s one of the great miracles of WW1 that the German side never knew, else the conflict may have ended, very differently.

Massive French losses stemming from the failed Nivelle offensive of that same month (French casualties were fully ten times what was expected) combined with irrational expectations that American forces would materialize on the western front led to massive unrest in the French lines. Fully one-half of all French forces on the western front mutinied. It’s one of the great miracles of WW1 that the German side never knew, else the conflict may have ended, very differently.

The “sealed train‘ carrying the plague bacillus of communism had already entered the Russian body politic. Nicholas II, Emperor of all Russia, was overthrown and murdered that July, along with his wife, children, servants and a few loyal friends, and their dogs.

This was the situation in July 1917.

For eighteen months, British miners worked to dig tunnels under Messines Ridge, the German defensive works laid out around the Belgian town of Ypres. Nearly a million pounds of high explosive were placed in some 2,000′ of tunnels, dug 100′ deep. 10,000 German soldiers ceased to exist at 3:10am local time on June 7, in a blast that could be heard as far away, as London.

For eighteen months, British miners worked to dig tunnels under Messines Ridge, the German defensive works laid out around the Belgian town of Ypres. Nearly a million pounds of high explosive were placed in some 2,000′ of tunnels, dug 100′ deep. 10,000 German soldiers ceased to exist at 3:10am local time on June 7, in a blast that could be heard as far away, as London.

Buoyed by this success and eager to destroy the German submarine bases on the Belgian coast, General Sir Douglas Haig planned an assault from the British-held Ypres salient, near the village of Passchendaele.

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George opposed the offensive, as did the French Chief of the General Staff, General Ferdinand Foch, both preferring to await the arrival of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). Historians have argued the wisdom of the move, ever since.

The third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, began in the early morning hours of July 31, 1917. The next 105 days would be fought under some of the most hideous conditions, of the entire war.

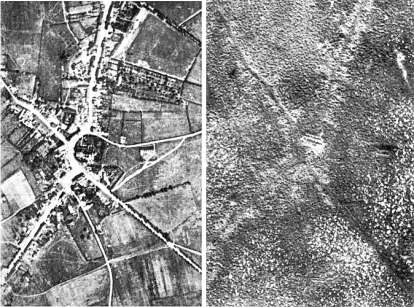

In the ten days leading up to the attack, some 3,000 guns fired an estimated 4½ million shells into German lines, pulverizing whole forests and smashing water control structures in the lowland plains. Several days into the attack, Ypres suffered the heaviest rainfall, in thirty years.

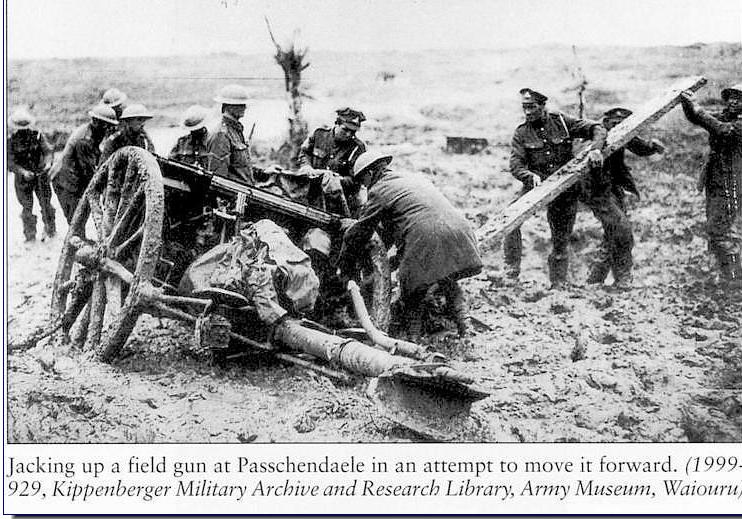

Conditions defy description. Time and again the clay soil, the water, the shattered remnants of once-great forests and the bodies of the slain were churned up and pulverized, by shellfire. You couldn’t call the stuff these people lived and fought in mud – it was more like a thick slime, a clinging, sucking ooze, capable of claiming grown men, even horses and mules. Most of the offensive took place across a broad plain formerly crisscrossed with canals, but now a great, sucking mire in which the only solid ground seemed to be German positions, from which machine guns cut down sodden commonwealth soldiers, as with a scythe.

Soldiers begged for their friends to shoot them, rather than being left to sink in that muck. One sank up to his neck and slowly went stark raving mad, as he died of thirst. British soldier Charles Miles wrote “It was worse when the mud didn’t suck you down; when it yielded under your feet you knew that it was a body you were treading on.”

In 105 days of this hell, Commonwealth forces lost 275,000 killed, wounded and missing. The German side another 200,000. 90,000 bodies were never identified. 42,000 were never recovered and remain there, to this day. All for five miles of mud, and a village barely recognizable, after its capture.

Following the battle of Passchendaele, staff officer Sir Launcelot Kiggell is said to have broken down in tears. “Good God”, he said, “Did we really send men to fight in That”?! The soldier turned war poet Siegfried Sassoon reveals the bitterness of the average “Joe Squaddy” whom his government had sent sent to fight and die, at Passchendaele. The story is told in the first person by a dead man, in all the bitterness of which the poet is capable. It’s called:

Memorial Tablet – by Siegfried Sassoon

“Squire nagged and bullied till I went to fight,

“Squire nagged and bullied till I went to fight,

(Under Lord Derby’s Scheme). I died in hell (They called it Passchendaele). My wound was slight,

And I was hobbling back; and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duck-boards: so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.

At sermon-time, while Squire is in his pew,

He gives my gilded name a thoughtful stare;

For, though low down upon the list, I’m there;

‘In proud and glorious memory’…that’s my due.

Two bleeding years I fought in France, for Squire:

I suffered anguish that he’s never guessed.

Once I came home on leave: and then went west…

What greater glory could a man desire?”

If you enjoyed this “Today in History”, please feel free to re-blog, “like” & share on social media, so that others may find and enjoy it as well. Please click the “follow” button on the right, to receive email updates on new articles. Thank you for your interest, in the history we all share.

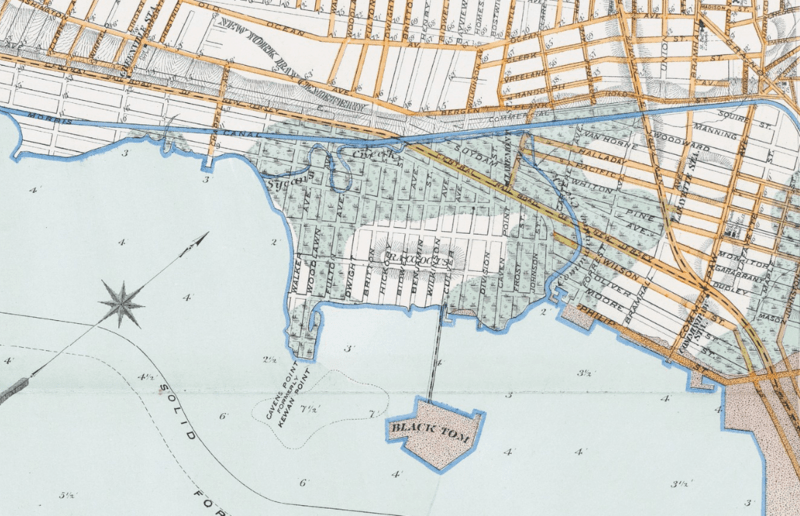

To the Central Powers, such trade had the sole purpose of killing their boys on the battlefields of Europe.

To the Central Powers, such trade had the sole purpose of killing their boys on the battlefields of Europe.

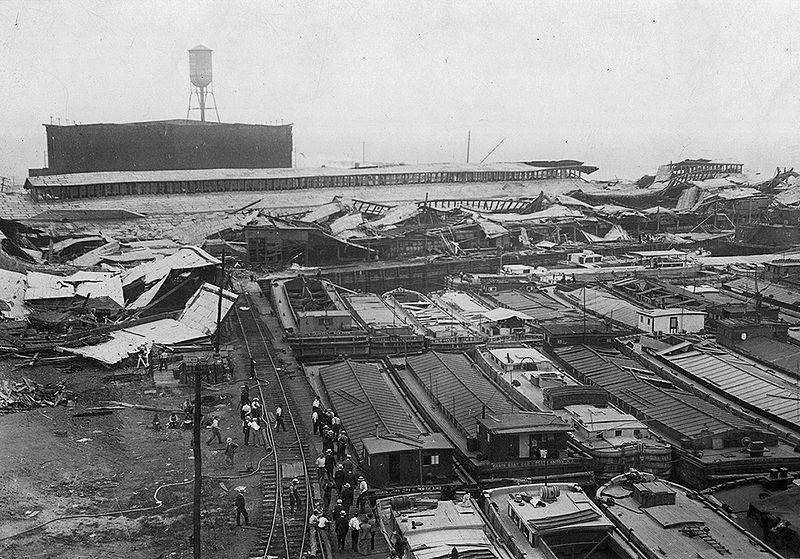

Known fatalities in the explosion included a Jersey City police officer, a Lehigh Valley Railroad Chief of Police, a ten week old infant, and the barge captain.

Known fatalities in the explosion included a Jersey City police officer, a Lehigh Valley Railroad Chief of Police, a ten week old infant, and the barge captain.

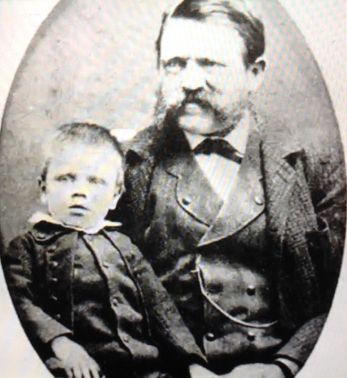

There are plenty of tales regarding the man’s paternity, but none are any more than that. Alois Schicklgruber ‘legitimized’ himself in 1877, adopting a variant on the name of his stepfather and calling himself ‘Hitler”.

There are plenty of tales regarding the man’s paternity, but none are any more than that. Alois Schicklgruber ‘legitimized’ himself in 1877, adopting a variant on the name of his stepfather and calling himself ‘Hitler”.

One such dog was “Chips”, the German Shepherd/Collie/Husky mix who would become the most decorated K-9 of WWII.

One such dog was “Chips”, the German Shepherd/Collie/Husky mix who would become the most decorated K-9 of WWII.

Often unseen in times of such dread calamity, are the humanitarian workers. Those who tend to the physical and spiritual requirements, the countless small comforts, of those so afflicted.

Often unseen in times of such dread calamity, are the humanitarian workers. Those who tend to the physical and spiritual requirements, the countless small comforts, of those so afflicted.

A small group of carefully selected female officers was sent to France on August 22. That first party comprised six men, three women and a married couple. Within fifteen months their number had expanded by a factor of 400.

A small group of carefully selected female officers was sent to France on August 22. That first party comprised six men, three women and a married couple. Within fifteen months their number had expanded by a factor of 400. ‘Hutments’ were formed all over the front, many right out at the front lines. There were canteen services. Religious observances of all denominations were held in these facilities. Concert performances were given, clothing mended and words of kindness offered in response to all manner of personal problems. On one occasion, the Loyal Order of Moose conducted a member initiation. Pies and cakes were baked in crude ovens and lemonade served to hot and thirsty troops. Of all these corporal works of mercy, the ones best remembered by the ‘doughboys’ themselves, were the doughnuts.

‘Hutments’ were formed all over the front, many right out at the front lines. There were canteen services. Religious observances of all denominations were held in these facilities. Concert performances were given, clothing mended and words of kindness offered in response to all manner of personal problems. On one occasion, the Loyal Order of Moose conducted a member initiation. Pies and cakes were baked in crude ovens and lemonade served to hot and thirsty troops. Of all these corporal works of mercy, the ones best remembered by the ‘doughboys’ themselves, were the doughnuts.

Before long, the women got better at it. Soon they were turning out 2,500 to 9,000 doughnuts a day. An elderly French blacksmith made Purviance a doughnut cutter, out of a condensed milk can and a camphor-ice tube, attached to a wooden block.

Before long, the women got better at it. Soon they were turning out 2,500 to 9,000 doughnuts a day. An elderly French blacksmith made Purviance a doughnut cutter, out of a condensed milk can and a camphor-ice tube, attached to a wooden block.

Fritz Duquesne was in charge of moving one of those shipments across the bushveld of Portuguese East Africa, when some kind of argument broke out. When it was over, only two wounded Boers were left alive, along with Duquesne himself and a few tottys (native porters). Duquesne ordered the tottys to hide the gold, burn the wagons and kill the survivors. He then rode off on an ox, having given the rest to the porters.

Fritz Duquesne was in charge of moving one of those shipments across the bushveld of Portuguese East Africa, when some kind of argument broke out. When it was over, only two wounded Boers were left alive, along with Duquesne himself and a few tottys (native porters). Duquesne ordered the tottys to hide the gold, burn the wagons and kill the survivors. He then rode off on an ox, having given the rest to the porters.

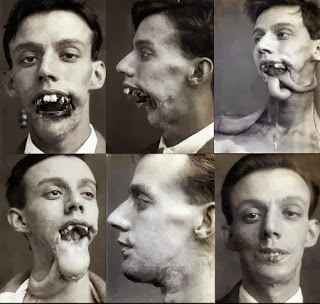

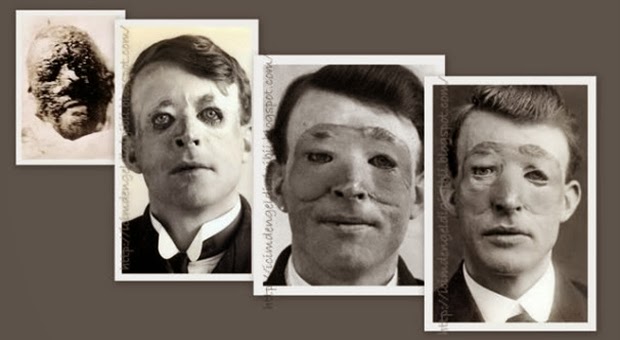

“Plastic” Surgery, the term comes to us from the Greek Plastikos and first used by the 18th century French surgeon Pierre Desault, has been with us longer than you might expect. Evidence exists of Hindu surgeons performing primitive ‘nose jobs’, as early as BC800-600. The Renaissance-era surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599) developed new methods of reconstruction, using the patient’s own arm skin to replace noses slashed off in swordplay.

“Plastic” Surgery, the term comes to us from the Greek Plastikos and first used by the 18th century French surgeon Pierre Desault, has been with us longer than you might expect. Evidence exists of Hindu surgeons performing primitive ‘nose jobs’, as early as BC800-600. The Renaissance-era surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599) developed new methods of reconstruction, using the patient’s own arm skin to replace noses slashed off in swordplay.

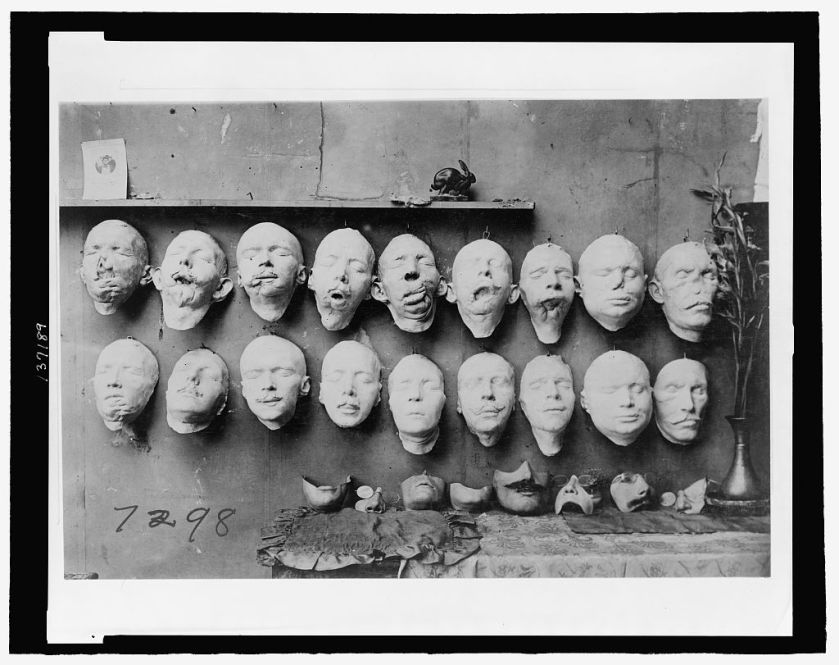

Ladd’s prostheses were uncomfortable to wear, but her services earned her the Légion d’Honneur Croix de Chevalier and the Serbian Order of Saint Sava.

Ladd’s prostheses were uncomfortable to wear, but her services earned her the Légion d’Honneur Croix de Chevalier and the Serbian Order of Saint Sava.

Dr. Gillies & Co. developed surgical methods in which rib cartilage is first implanted in foreheads, and then swung down to form the foundational structure of a new nose.

Dr. Gillies & Co. developed surgical methods in which rib cartilage is first implanted in foreheads, and then swung down to form the foundational structure of a new nose.

3,662,374 military service certificates were issued to qualifying veterans, bearing a face value equal to $1 per day of domestic service and $1.25 a day for overseas service, plus interest. Total face value of these certificates was $3.638 billion, equivalent to $43.7 billion in today’s dollars and coming to full maturity in 1945.

3,662,374 military service certificates were issued to qualifying veterans, bearing a face value equal to $1 per day of domestic service and $1.25 a day for overseas service, plus interest. Total face value of these certificates was $3.638 billion, equivalent to $43.7 billion in today’s dollars and coming to full maturity in 1945. The Great Depression was two years old in 1932, and thousands of veterans had been out of work since the beginning. Certificate holders could borrow up to 50% of the face value of their service certificates, but direct funds remained unavailable for another 13 years.

The Great Depression was two years old in 1932, and thousands of veterans had been out of work since the beginning. Certificate holders could borrow up to 50% of the face value of their service certificates, but direct funds remained unavailable for another 13 years. This had happened before. Hundreds of Pennsylvania veterans of the Revolution had marched on Washington in 1783, after the Continental Army was disbanded without pay.

This had happened before. Hundreds of Pennsylvania veterans of the Revolution had marched on Washington in 1783, after the Continental Army was disbanded without pay.

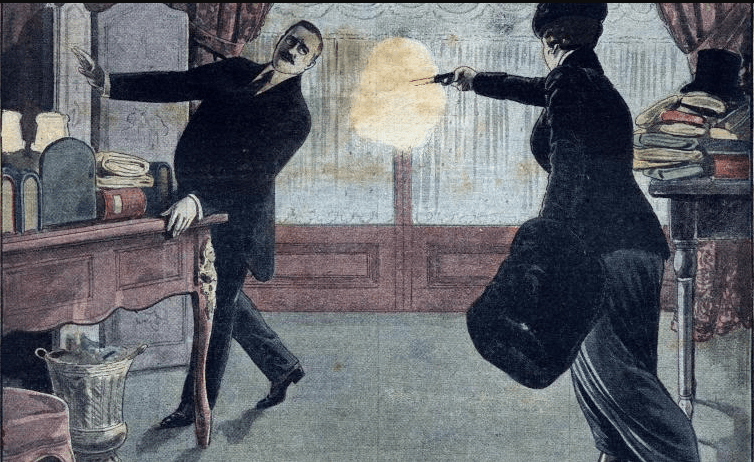

Marchers and their families were in their camps on July 28 when Attorney General William Mitchell ordered them evicted. Two policemen became trapped on the second floor of a building when they drew their revolvers and shot two veterans, William Hushka and Eric Carlson, both of whom died of their injuries.

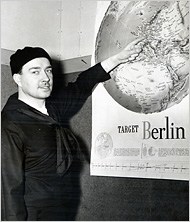

Marchers and their families were in their camps on July 28 when Attorney General William Mitchell ordered them evicted. Two policemen became trapped on the second floor of a building when they drew their revolvers and shot two veterans, William Hushka and Eric Carlson, both of whom died of their injuries. President Herbert Hoover ordered the Army under General Douglas MacArthur to evict the Bonus Army from Washington. 500 Cavalry formed up on Pennsylvania Avenue at 4:45pm, supported by 500 Infantry, 800 police and six battle tanks under the command of then-Major George S. Patton. Civil Service employees came out to watch as bonus marchers cheered, thinking that the Army had gathered in their support.

President Herbert Hoover ordered the Army under General Douglas MacArthur to evict the Bonus Army from Washington. 500 Cavalry formed up on Pennsylvania Avenue at 4:45pm, supported by 500 Infantry, 800 police and six battle tanks under the command of then-Major George S. Patton. Civil Service employees came out to watch as bonus marchers cheered, thinking that the Army had gathered in their support. Bonus marchers fled to their largest encampment across the Anacostia River, when President Hoover ordered the assault stopped. Feeling that the Bonus March was an attempt to overthrow the government, General MacArthur ignored the President and ordered a new attack, the army routing 10,000 and leaving their camps in flames. 1,017 were injured and 135 arrested.

Bonus marchers fled to their largest encampment across the Anacostia River, when President Hoover ordered the assault stopped. Feeling that the Bonus March was an attempt to overthrow the government, General MacArthur ignored the President and ordered a new attack, the army routing 10,000 and leaving their camps in flames. 1,017 were injured and 135 arrested. Then-Major Dwight D. Eisenhower was one of MacArthur’s aides at the time. Eisenhower believed that it was wrong for the Army’s highest ranking officer to lead an action against fellow war veterans. “I told that dumb son-of-a-bitch not to go down there”, he said.

Then-Major Dwight D. Eisenhower was one of MacArthur’s aides at the time. Eisenhower believed that it was wrong for the Army’s highest ranking officer to lead an action against fellow war veterans. “I told that dumb son-of-a-bitch not to go down there”, he said. The bonus march debacle doomed any chance that Hoover had of being re-elected. Franklin D. Roosevelt opposed the veterans’ bonus demands during the election, but was able to negotiate a solution when veterans organized a second demonstration in 1933. Roosevelt’s wife Eleanor was instrumental in these negotiations, leading one veteran to quip: “Hoover sent the army. Roosevelt sent his wife”.

The bonus march debacle doomed any chance that Hoover had of being re-elected. Franklin D. Roosevelt opposed the veterans’ bonus demands during the election, but was able to negotiate a solution when veterans organized a second demonstration in 1933. Roosevelt’s wife Eleanor was instrumental in these negotiations, leading one veteran to quip: “Hoover sent the army. Roosevelt sent his wife”.

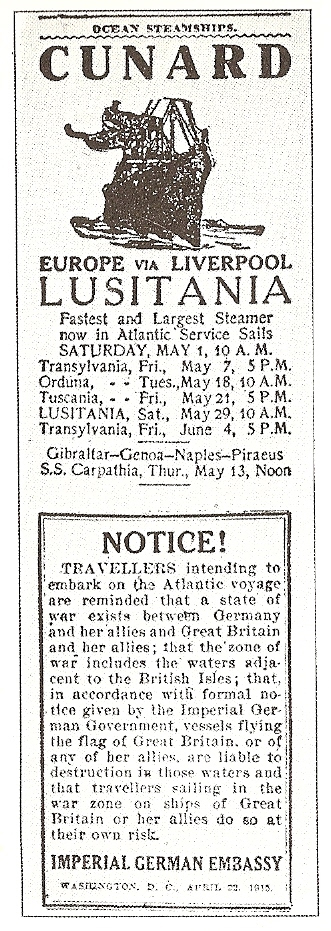

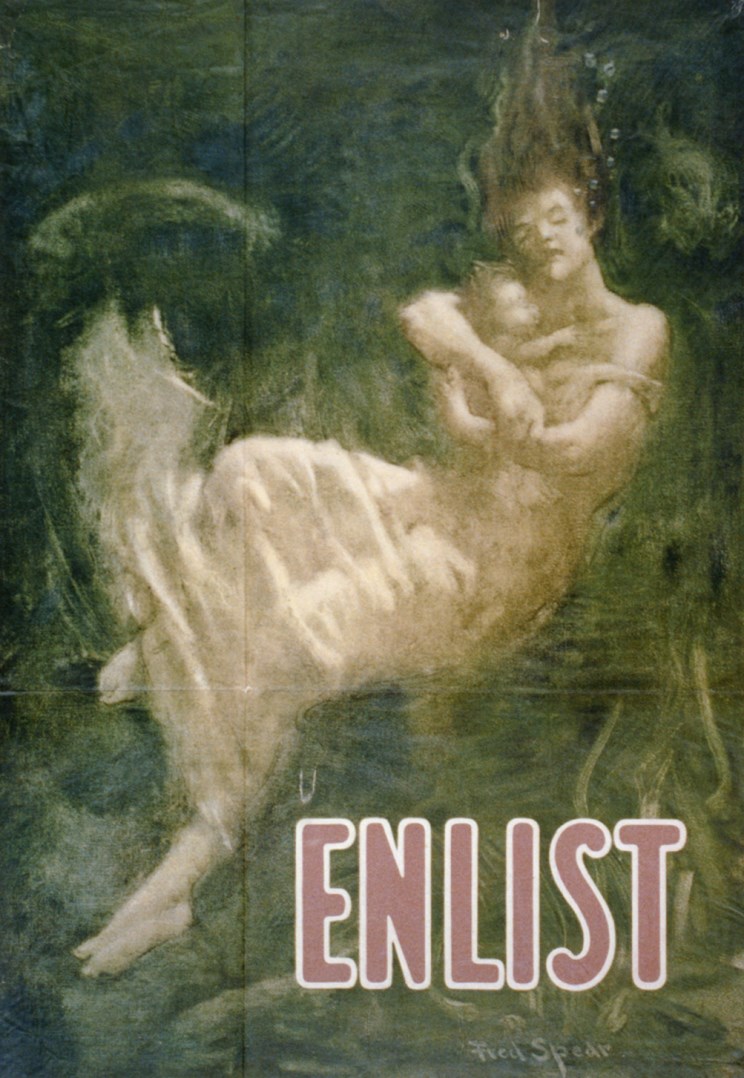

Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare on February 18, 1915. The German embassy took out ads in American newspapers, warning that ships sailing into the war zone, did so at their own risk. That didn’t seem to bother anyone as they boarded RMS Lusitania.

Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare on February 18, 1915. The German embassy took out ads in American newspapers, warning that ships sailing into the war zone, did so at their own risk. That didn’t seem to bother anyone as they boarded RMS Lusitania.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed the same month. In February a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California off the Irish coast, killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew. President Wilson asked for a declaration of war in a speech to a joint session of Congress on April 2. From the text of the speech, it seems the Germans were right. It was the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare which provoked the United States to enter the war against Germany, which it did when Congress declared war on April 6.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed the same month. In February a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California off the Irish coast, killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew. President Wilson asked for a declaration of war in a speech to a joint session of Congress on April 2. From the text of the speech, it seems the Germans were right. It was the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare which provoked the United States to enter the war against Germany, which it did when Congress declared war on April 6.

You must be logged in to post a comment.