The final third of the nineteenth century was a period of unprecedented technological advancement, an industrial revolution of international proportion.

The war born of the second industrial revolution, would be like none before.

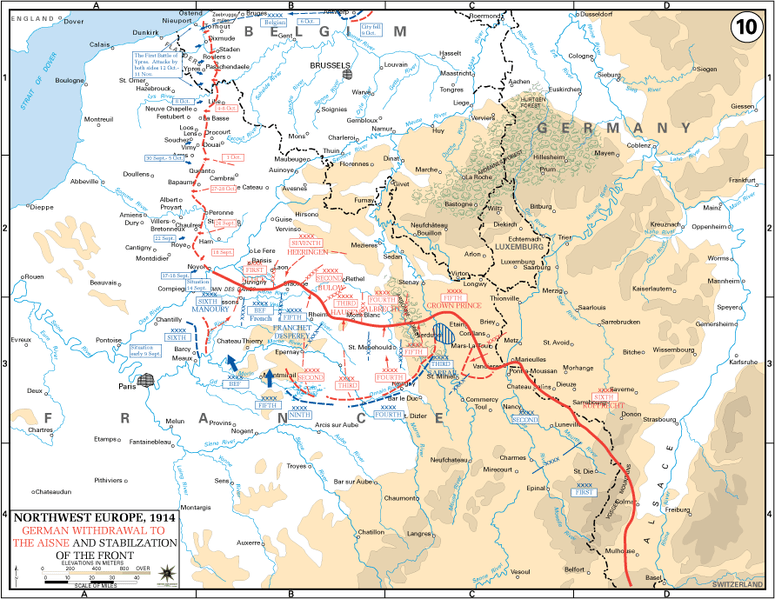

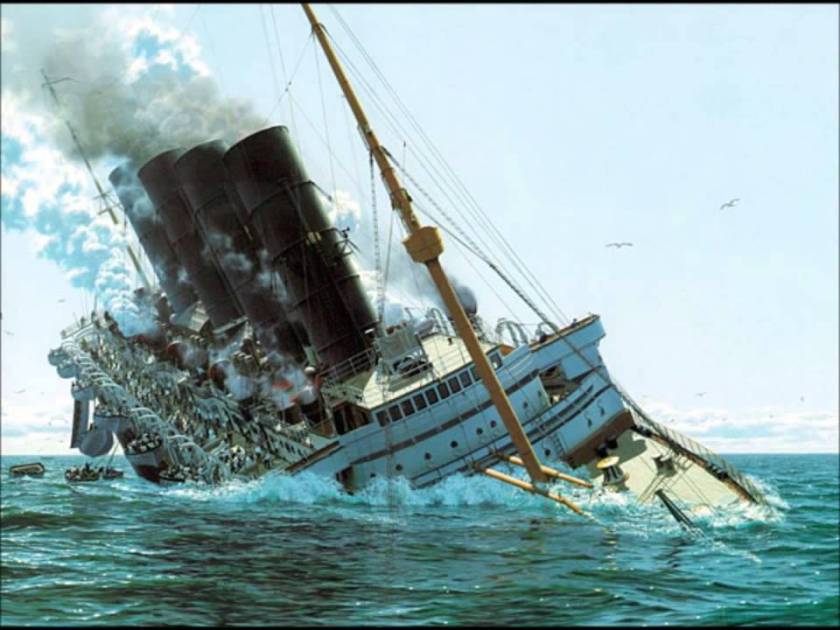

From the earliest days of the “War to end all Wars”, the Triple Entente powers imposed a surface blockade on the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, throttling the maritime supply of goods and crippling the capacity to make war. One academic study from 1928 put the death toll by starvation at 424,000, in Germany alone.

The Kaiser responded with a blockade of his own, a submarine attack on the supply chain to the British home islands. It was a devastating incursion against an island adversary dependent on prodigious levels of imports.

1915 saw the first German attacks on civilian shipping. Total losses for that year alone came to 370 vessels against a loss of only 16 U-Boats. Steel was in critically short supply by the time the US entered the war in 1917 with the need for new ships, higher than ever. Something had to be done. One answer, was concrete.

The idea of concrete boats was nothing new. In the south of France, Joseph Louis Lambot experimented with steel-reinforced “ferrocement”, building his first dinghy in 1848.

By the outbreak of WW1, Lambot’s creation had sunk to the bottom of a lake, where it remained for 100 years, buried deep in anaerobic mud. Today you may see the thing at the Museum of Brignoles, in the south of France.

Italian engineer Carlo Gabellini built barges and small ships of concrete in the 1890s. British boat builders experimented with the stuff, in the first decade of the 20th century. The Violette, built in Faversham in 1917, is now a mooring hulk in Kent, the oldest concrete vessel still afloat.

The Violette built in 1917, is the oldest concrete ship, still afloat.

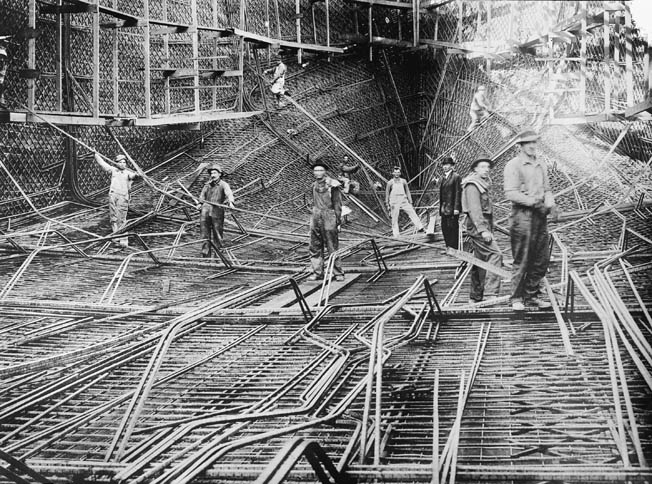

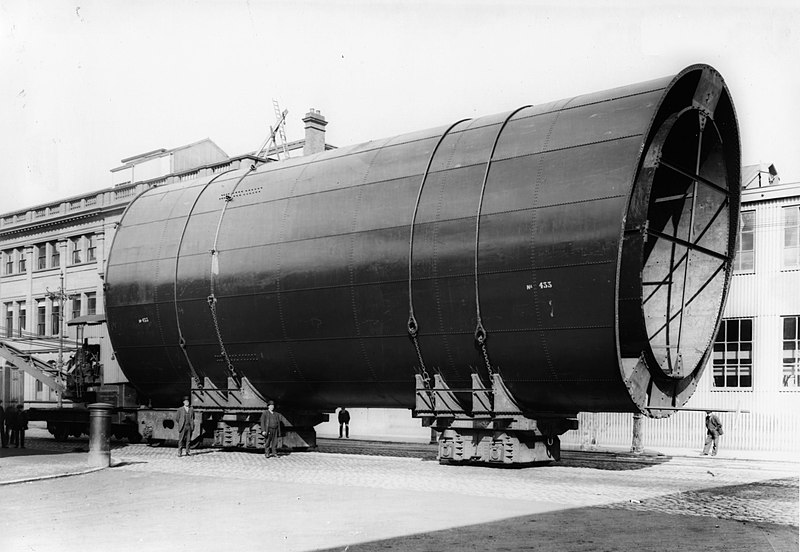

The American government contracted with Norwegian boat builder N.K. Fougner to create a prototype, the 84-foot Namsenfjord launched in August, 1917. The test was judged a success. President Woodrow Wilson approved a twenty-four ship fleet, consisting of steamers and tankers to aid the war effort. The first and largest of the concrete fleet, the SS Faith was launched on this day in 1918, thirty days ahead of schedule.

The New York Times was ecstatic:

‘”When the first steel vessels were built people said they would not float, or if they did they would be too heavy to be serviceable,” said W. Leslie Comyn, President of the concern which built the boat. “Now they say the same about concrete. But all the engineers we have taken over this boat, including many who said it was an impossible undertaking, now agree that it was a success”‘.

‘”When the first steel vessels were built people said they would not float, or if they did they would be too heavy to be serviceable,” said W. Leslie Comyn, President of the concern which built the boat. “Now they say the same about concrete. But all the engineers we have taken over this boat, including many who said it was an impossible undertaking, now agree that it was a success”‘.

All that from a west coast meadow with two tool sheds, a production facility 1/20th the cost of a conventional steel shipyard.

The Great War ended eight months later with only half the concrete fleet, actually begun. None were completed. All were sold off to commercial shippers or for storage, or scrap.

For all its advantages as a building material, ferrocement has numerous drawbacks. Concrete is a porous material, and chunks tend to spall off from rusting steel reinforcements. We’ve all see that on bridge abutments. Worst of all, the stuff is brittle. On October 30, 1920, the SS Cape Fear collided with a cargo ship in Narragansett Bay Rhode Island and “shattered like a teacup”, killing 19 crewmen.

SS Palo Alto was a tanker-turned restaurant and dance club, before breaking up in heavy waves, in Monterey Bay.

SS San Pasqual was damaged in a storm in 1921 and became a warehouse for the Old Times Molasses Company of Havana. She was converted to a coastal defense installation during WW2 and outfitted with machine guns and cannon, then becaming a prison, during the Cuban revolution. The wreck was later converted to a 10-room hotel before closing, for good. That was some swanky joint, I’m sure.

The steamer SS Sapona was sold for scrap and converted to a floating liquor warehouse during Prohibition, later grounding off the shore of Bimini during a hurricane. All the liquor, was lost.

The SS Atlantus was destined to be sunk in place as a ferry dock in Cape May New Jersey in 1926, until she broke free in a hurricane and ran aground, 150-feet from the beach. Several attempts were made to free the hulk, but none successful. At one time, the wreck bore a billboard. Advertising a marine insurance outfit, no less. Kids used to swim out and dive off, until one drowned. The wreck began to split up in the late 1950s. If you visit sunset beach today, you might see something like the image, at the top of this page.

In 1942, the world once again descended into war. With steel again in short supply, the Roosevelt administration contracted for another concrete fleet of 24 ships. The decades had come and gone since that earlier fleet. This time, the new vessels came off the production line at the astonishing rate of one a month featuring newer and stronger aggregates, lighter than those of years past. Like the earlier concrete fleet, most would be sold off after the war. Two of the WW2 concrete fleet actually saw combat service, the SS David O. Saylor and the SS Vitruvius.

In March 1944, an extraordinary naval convoy departed the port of Baltimore. including the concrete vessels, SS David O. Saylor and SS Vitruvius. It was the most decrepit procession to depart an American city since Ma and Pa Joad left Oklahoma, for California. A one-way voyage with Merchant Marines promised a return trip, aboard Queen Mary.

Merchant mariner Richard Powers , described the scene:

“We left Baltimore on March 5, and met our convoy just outside Charleston, South Carolina,” Powers recalled. “It wasn’t a pretty sight: 15 old ‘rustpots.’ There were World War I-era ‘Hog Islanders’ (named for the Hog Island shipyard in Philadelphia where these cargo and transport ships were built), damaged Liberty Ships.”

1,154 U-boats were commissioned into the German navy before and during WW2, some 245 of which were lost in 1944. The majority of those, in the North Atlantic. The allied crossing took a snail’s pace at 33 days and, despite the massive U-boat presence, passed unmolested into Liverpool. Powers figured, “The U-Boats were not stupid enough to waste their torpedoes on us.”

Herr Hitler’s Kriegsmarine should have paid more attention.

On June 1, Seaman Powers’ parade of misfit ships joined a procession of 100 British and American vessels. Old transports and battered warships, under tow or limping across the English channel at the stately pace of five knots. These were the old and the infirm, the combat damaged and obsolete. There were gaping holes from mine explosions, and the twisted and misshapen evidence of collisions at sea. Some had superstructures torn by some of the most vicious naval combat, of the European war. Decrepit as they were, each was bristling with anti-aircraft batteries, Merchant Mariners joined by battle hardened combat troops.

Their services would not be required. The allies had complete air supremacy over the English channel.

These were the “gooseberries” and “blockships”. Part of the artificial “Mulberry” harbors intended to form breakwaters and landing piers in support of the D-Day landing, charged with the difficult and dangerous task of scuttling under fire at five points along the Norman coast. Utah. Omaha. Gold. Juneau. Sword.

Later on, thousands more merchant vessels would arrive in support of the D-Day invasion. None more important than those hundred or so destined to advance and die, the living breakwater without which the retaking of continental Europe, would not have been possible.

When the “Great War” broke out in 1914, US Armed Forces were small compared with the mobilized forces of the European powers. The Selective Service Act, enacted May 18, 1917, authorized the federal government to raise an army for the United States’ entry into WWI. Two months after the American declaration of war against Imperial Germany, a mere 14,000 American soldiers had arrived “over there”. Eleven months later, that number stood at well over a million.

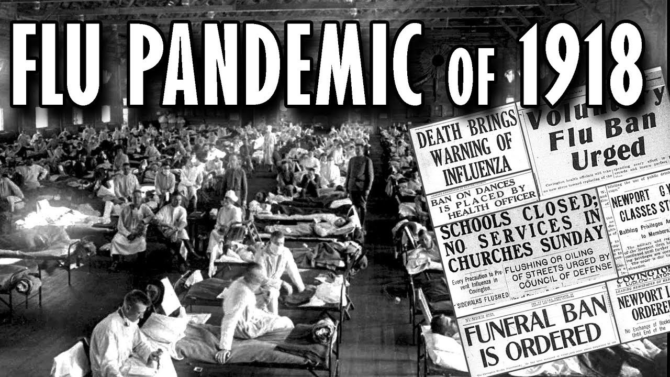

When the “Great War” broke out in 1914, US Armed Forces were small compared with the mobilized forces of the European powers. The Selective Service Act, enacted May 18, 1917, authorized the federal government to raise an army for the United States’ entry into WWI. Two months after the American declaration of war against Imperial Germany, a mere 14,000 American soldiers had arrived “over there”. Eleven months later, that number stood at well over a million. On the morning of March 11, 1918, most of the recruits at Fort Riley, Kansas, were turning out for breakfast. Private Albert Gitchell reported to the hospital, complaining of cold-like symptoms of sore throat, fever and headache. By noon, more than 100 more had reported sick with similar symptoms.

On the morning of March 11, 1918, most of the recruits at Fort Riley, Kansas, were turning out for breakfast. Private Albert Gitchell reported to the hospital, complaining of cold-like symptoms of sore throat, fever and headache. By noon, more than 100 more had reported sick with similar symptoms.

Over the next two years, this strain of flu infected one in every four people in the United States, killing an estimated 675,000 Americans. Eight million died in Spain alone, following an initial outbreak in May. Forever after, the pandemic would be known as the Spanish Flu.

Over the next two years, this strain of flu infected one in every four people in the United States, killing an estimated 675,000 Americans. Eight million died in Spain alone, following an initial outbreak in May. Forever after, the pandemic would be known as the Spanish Flu.

The Forgotten World War

The Forgotten World War

Operation E.C.1 was a planned exercise for the British Grand Fleet, scheduled for February 1, 1918 out of the naval anchorage at Scapa Flow in the North Sea Orkney Islands.

Operation E.C.1 was a planned exercise for the British Grand Fleet, scheduled for February 1, 1918 out of the naval anchorage at Scapa Flow in the North Sea Orkney Islands.

Cornered in a washout under some railroad tracks, single handed, Randall held off the attack with his revolver, despite a gunshot wound to his shoulder and no fewer than 11 lance wounds.

Cornered in a washout under some railroad tracks, single handed, Randall held off the attack with his revolver, despite a gunshot wound to his shoulder and no fewer than 11 lance wounds.

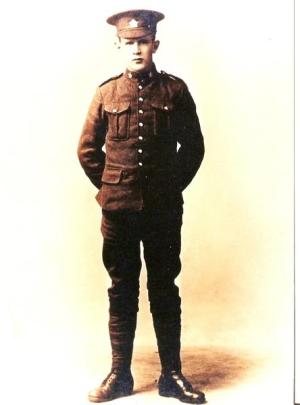

1st Sergeant Mark Matthews, the last of the Buffalo Soldiers, died of pneumonia on September 6, 2005 at age of 111. A man who forged papers in order to join at age fifteen and once had to play taps from the woods, was buried with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, section 69, grave #4215.

1st Sergeant Mark Matthews, the last of the Buffalo Soldiers, died of pneumonia on September 6, 2005 at age of 111. A man who forged papers in order to join at age fifteen and once had to play taps from the woods, was buried with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, section 69, grave #4215.

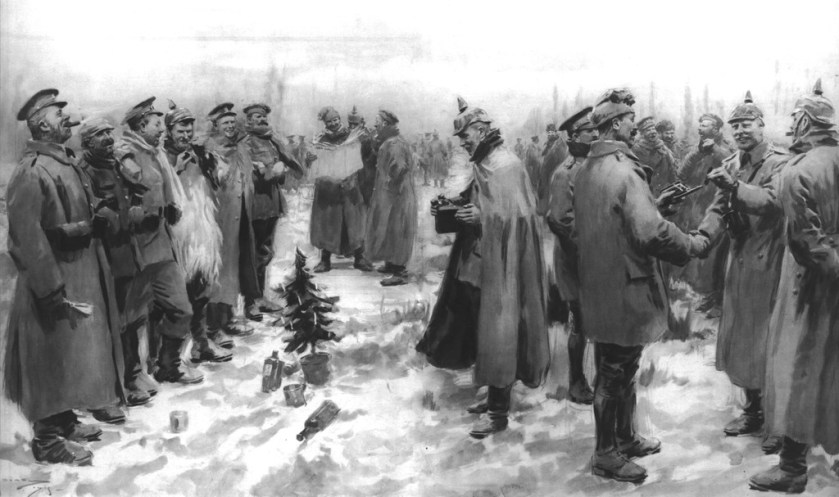

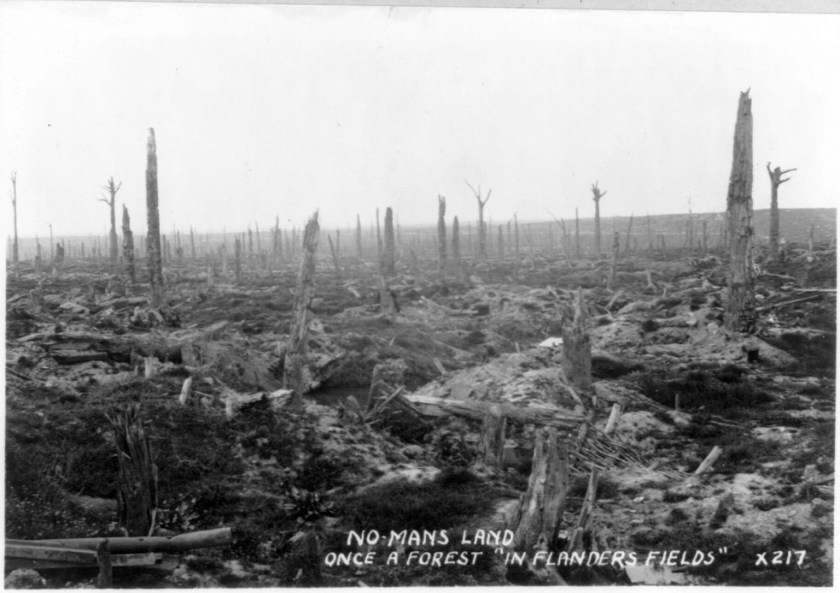

On the Western Front, it rained for much of November and December that first year. The no man’s land between British and German trenches was a wasteland of mud and barbed wire. Christmas Eve, 1914 dawned cold and clear. The frozen ground allowed men to move about for the first time in weeks. That evening, English soldiers heard singing. The low sound of a Christmas carol, drifting across no man’s land…Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht…Silent Night.

On the Western Front, it rained for much of November and December that first year. The no man’s land between British and German trenches was a wasteland of mud and barbed wire. Christmas Eve, 1914 dawned cold and clear. The frozen ground allowed men to move about for the first time in weeks. That evening, English soldiers heard singing. The low sound of a Christmas carol, drifting across no man’s land…Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht…Silent Night.

Captain Sir Edward Hulse Bart reported a sing-song which “ended up with ‘Auld lang syne’ which we all, English, Scots, Irish, Prussians, Wurttenbergers, etc, joined in. It was absolutely astounding, and if I had seen it on a cinematograph film I should have sworn that it was faked!”

Captain Sir Edward Hulse Bart reported a sing-song which “ended up with ‘Auld lang syne’ which we all, English, Scots, Irish, Prussians, Wurttenbergers, etc, joined in. It was absolutely astounding, and if I had seen it on a cinematograph film I should have sworn that it was faked!”

Curley was as good as his word. The Mayor and Massachusetts’ Governor Samuel McCall composed a Halifax Relief Committee to raise funds and organize aid. McCall reported the effort raised $100,000 in its first hour alone, equivalent to over $1.9 million, today.

Curley was as good as his word. The Mayor and Massachusetts’ Governor Samuel McCall composed a Halifax Relief Committee to raise funds and organize aid. McCall reported the effort raised $100,000 in its first hour alone, equivalent to over $1.9 million, today.

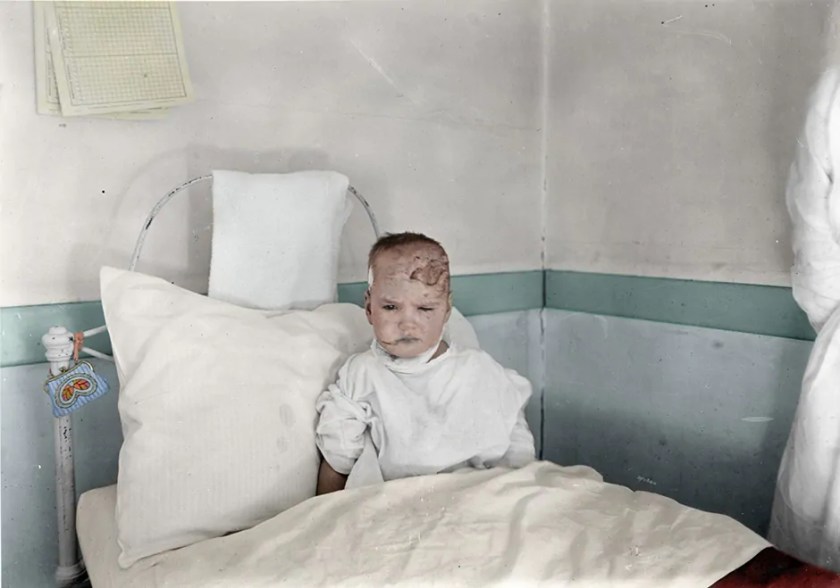

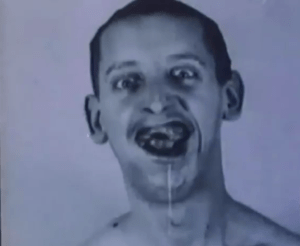

The worldwide Encephalitis Lethargica epidemic afflicted some five million people between 1915 and 1924. One-third of sufferers died in the acute phase of the disease, a higher mortality rate than the Spanish flu of 1918-’19. Many of those who survived never returned to their pre-existing state of “aliveness”, and lived the rest of their lives institutionalized, as described above.

The worldwide Encephalitis Lethargica epidemic afflicted some five million people between 1915 and 1924. One-third of sufferers died in the acute phase of the disease, a higher mortality rate than the Spanish flu of 1918-’19. Many of those who survived never returned to their pre-existing state of “aliveness”, and lived the rest of their lives institutionalized, as described above. Individual cases continue to pop up, but have never assumed the pandemic proportions of 1915-’24. Further study is needed but, perversely, such study is only possible given more cases of the disease. For now, Encephalitis Lethargica must remain one of the great medical mysteries of the twentieth century. An epidemiological conundrum, locked away in a nightmare closet of forgotten memory.

Individual cases continue to pop up, but have never assumed the pandemic proportions of 1915-’24. Further study is needed but, perversely, such study is only possible given more cases of the disease. For now, Encephalitis Lethargica must remain one of the great medical mysteries of the twentieth century. An epidemiological conundrum, locked away in a nightmare closet of forgotten memory.

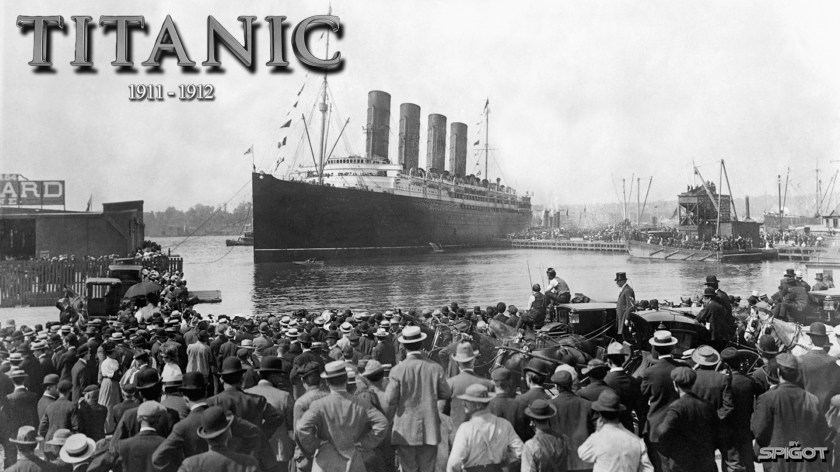

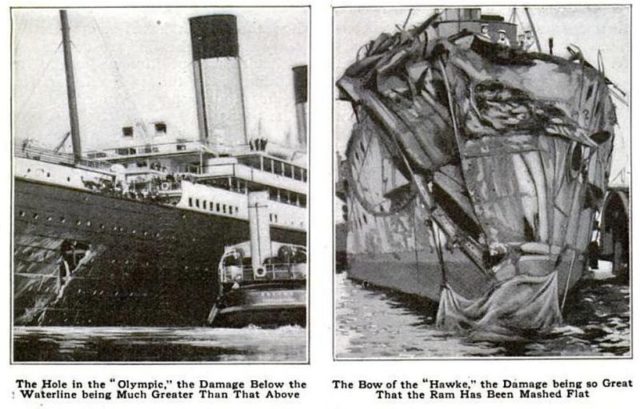

The ship was built to survive flooding in four watertight compartments. The iceberg had opened five. As Titanic began to lower at the bow, it soon became clear that the ship was doomed.

The ship was built to survive flooding in four watertight compartments. The iceberg had opened five. As Titanic began to lower at the bow, it soon became clear that the ship was doomed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.