“Listen my children and you shall hear,

Of the midnight ride of” …Sybil Ludington.

Wait…What?

Paul Revere’s famous “midnight ride” began on the night of April 18, 1775. Revere was one of two riders, soon joined by a third, fanning out from Boston to warn of an oncoming column of “regulars”, come to destroy the stockpile of gunpowder, ammunition, and cannon in Concord.

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

Revere himself covered barely 12 miles before being captured, his horse confiscated to replace the tired mount of a British sergeant. Revere would finish his “ride” on foot, arriving at sunrise on the 19th to witness the last moments of the battle on Lexington Green.

Two years later, Patriot forces maintained a similar supply depot, in the southwest Connecticut town of Danbury.

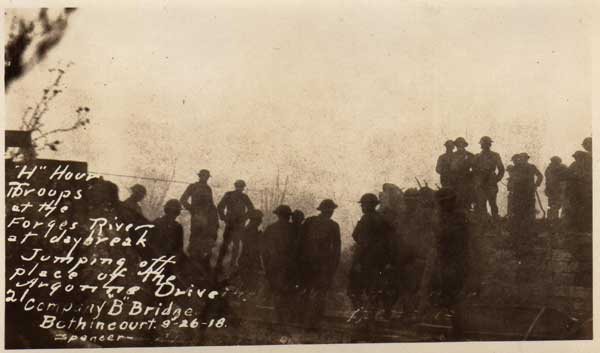

William Tryon was the Royal Governor of New York, and long-standing advocate for attacks on civilian targets. In 1777, Tryon was major-general of the provincial army. On April 25th, the General set sail for the Connecticut coast of Long Island Sound with a force of 1,800, intending to destroy Danbury.

Patriot Colonel Joseph Cooke’s small Danbury garrison was caught and quickly overpowered on the 26th, trying to remove food supplies, uniforms, and equipment. Facing little if any opposition, Tryon’s forces went on a bender, burning homes, farms and storehouses. Thousands of barrels of pork, beef, and flour were destroyed, along with 5,000 pairs of shoes, 2,000 bushels of grain, and 1,600 tents.

Colonel Henry Ludington was a farmer and father of 12, with a long military career. A long-standing and loyal subject of the British crown, Ludington switched sides in 1773, joining the rebel cause and rising to command the 7th Regiment of the Dutchess County Militia, in New York’s Hudson Valley.

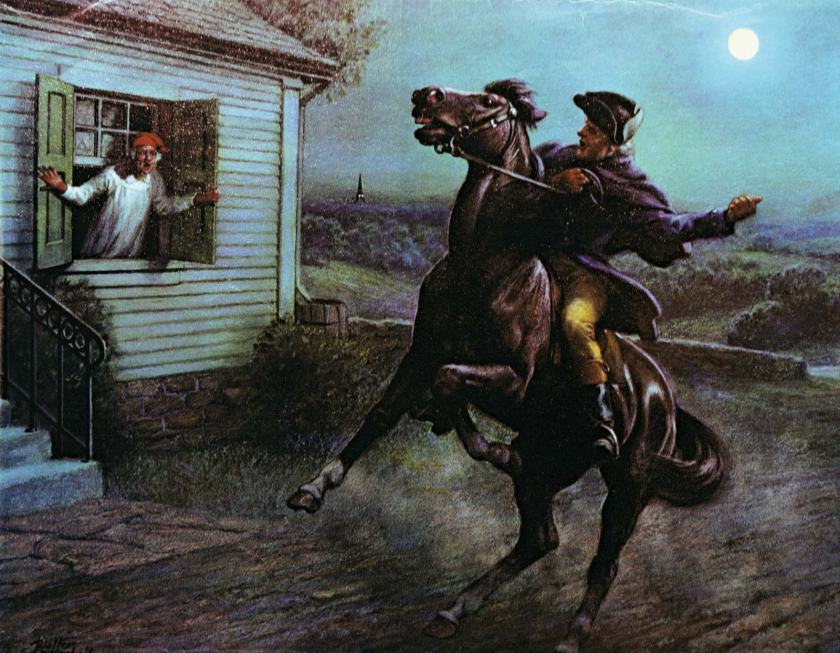

In April 1777, Ludington’s militia was disbanded for planting season, and spread across the countryside. An exhausted rider arrived at the Ludington farm on a blown horse, on the evening of the 26th, asking for help. 15 miles away, British regulars and a force of loyalists were burning Danbury to the ground.

The Dutchess County Militia had to be called up. The Colonel had one night to prepare for battle, and this rider was done. The job would have to go to Colonel Ludington’s first-born, his daughter, Sybil.

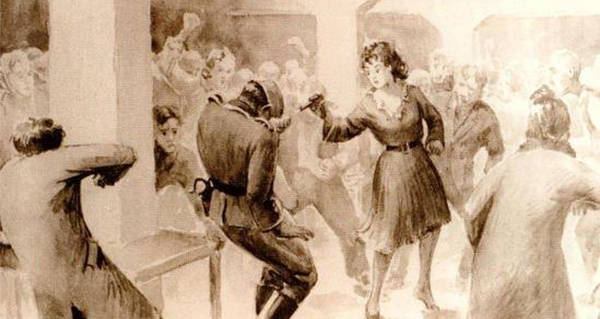

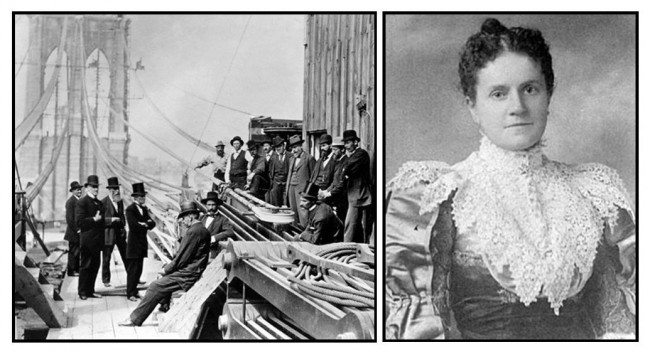

Born April 5, 1761, Sybil Ludington was barely sixteen at the time of her ride. From Poughkeepsie to what is now Putnam County and back, the “Female Paul Revere” rode across the lower Hudson River Valley, covering 40 miles in the pitch dark of night, alerting her father’s militia to the danger and urging them to come out and fight. She’d use a stick to knock on doors, even using it once, to fight off a highway bandit.

By the time Sybil returned the next morning, cold, rain-soaked, and exhausted, most of 400 militia were ready to march.

Arnold’s forces arrived too late to save Danbury, but inflicted a nasty surprise on the British rearguard as the column approached nearby Ridgefield. Never outnumbered by less than three-to-one, Connecticut militia was able to slow the British advance until Ludington’s New York Militia arrived on the following day. The last phase of the action saw the same type of swarming harassment, as seen on the British retreat from Concord to Boston, early in the war.35 miles to the east of Danbury, General Benedict Arnold was gathering a force of 500 regular and irregular Connecticut militia, with Generals David Wooster and Gold Selleck Silliman.

Though the British operation was a tactical success, the mauling inflicted by these colonials ensured that this was the last hostile British landing on the Connecticut coast.

The British raid on Danbury destroyed at least 19 houses and 22 stores and barns. Town officials submitted £16,000 in claims to Congress, for which town selectmen received £500 reimbursement. Further claims were made to the General Assembly of Connecticut in 1787, for which Danbury was awarded land. In Ohio.

At the time, Benedict Arnold planned to travel to Philadelphia, to protest the promotion of officers junior to himself, to Major General. Arnold, who’d had two horses shot out from under him at Ridgefield, was promoted to Major General in recognition for his role in the battle. Along with that promotion came a horse, “properly caparisoned as a token of … approbation of his gallant conduct … in the late enterprize to Danbury.” For now, the pride which would one day be his undoing, was assuaged.The Keeler Tavern in Ridgefield is now a museum. The British cannonball fired into the side of the building, remains there to this day.

Henry Ludington would become Aide-de-Camp to General George Washington, and grandfather to Harrison Ludington, mayor of Milwaukee and 12th Governor of Wisconsin.

Gold Silliman was kidnapped with his son by a first marriage by Tory neighbors, and held for Nearly seven months at a New York farmhouse. Having no hostage of equal rank with whom to exchange for the General, Patriot forces went out and kidnapped one of their own, in the person of Chief Justice Judge Thomas Jones, of Long Island.

Mary Silliman was left to run the farm, including caring for her own midwife, who was brutally raped by English forces for denying them the use of her home. The 1993 made-for-TV movie “Mary Silliman’s War” tells the story of non-combatants, pregnant mothers and farm wives during the Revolution, as well as Mary’s own negotiations for her husband’s release from his Loyalist captors.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

General David Wooster was mortally wounded at the Battle of Ridgefield, moments after shouting “Come on my boys! Never mind such random shots!” Today, an archway marks the entrance to Wooster Square, in the East Rock Neighborhood of New Haven.

Sybil Ludington received the thanks of family and friends and even that of George Washington. She then stepped off the pages of history.

Paul Revere’s famous ride would have likewise faded into obscurity, but for the poetry of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Eighty-six years, later.

“Listen my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year. He said to his friend, “If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light,–

One if by land, and two if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm. ”Then he said “Good-night!” and with muffled oar

Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore,

Just as the moon rose over the bay,

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war;

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar

Across the moon like a prison bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide. Meanwhile, his friend through alley and street

Wanders and watches, with eager ears,

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers,

Marching down to their boats on the shore. Then he climbed the tower of the Old North Church,

By the wooden stairs, with stealthy tread,

To the belfry chamber overhead,

And startled the pigeons from their perch

On the sombre rafters, that round him made

Masses and moving shapes of shade,–

By the trembling ladder, steep and tall,

To the highest window in the wall,

Where he paused to listen and look down

A moment on the roofs of the town

And the moonlight flowing over all. Beneath, in the churchyard, lay the dead,

In their night encampment on the hill,

Wrapped in silence so deep and still

That he could hear, like a sentinel’s tread,

The watchful night-wind, as it went

Creeping along from tent to tent,

And seeming to whisper, “All is well!”

A moment only he feels the spell

Of the place and the hour, and the secret dread

Of the lonely belfry and the dead;

For suddenly all his thoughts are bent

On a shadowy something far away,

Where the river widens to meet the bay,–

A line of black that bends and floats

On the rising tide like a bridge of boats. Meanwhile, impatient to mount and ride,

Booted and spurred, with a heavy stride

On the opposite shore walked Paul Revere.

Now he patted his horse’s side,

Now he gazed at the landscape far and near,

Then, impetuous, stamped the earth,

And turned and tightened his saddle girth;

But mostly he watched with eager search

The belfry tower of the Old North Church,

As it rose above the graves on the hill,

Lonely and spectral and sombre and still.

And lo! as he looks, on the belfry’s height

A glimmer, and then a gleam of light!

He springs to the saddle, the bridle he turns,

But lingers and gazes, till full on his sight

A second lamp in the belfry burns.A hurry of hoofs in a village street,

A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,

And beneath, from the pebbles, in passing, a spark

Struck out by a steed flying fearless and fleet;

That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light,

The fate of a nation was riding that night;

And the spark struck out by that steed, in his flight,

Kindled the land into flame with its heat.

He has left the village and mounted the steep,

And beneath him, tranquil and broad and deep,

Is the Mystic, meeting the ocean tides;

And under the alders that skirt its edge,

Now soft on the sand, now loud on the ledge,

Is heard the tramp of his steed as he rides. It was twelve by the village clock

When he crossed the bridge into Medford town.

He heard the crowing of the cock,

And the barking of the farmer’s dog,

And felt the damp of the river fog,

That rises after the sun goes down. It was one by the village clock,

When he galloped into Lexington.

He saw the gilded weathercock

Swim in the moonlight as he passed,

And the meeting-house windows, black and bare,

Gaze at him with a spectral glare,

As if they already stood aghast

At the bloody work they would look upon. It was two by the village clock,

When he came to the bridge in Concord town.

He heard the bleating of the flock,

And the twitter of birds among the trees,

And felt the breath of the morning breeze

Blowing over the meadow brown.

And one was safe and asleep in his bed

Who at the bridge would be first to fall,

Who that day would be lying dead,

Pierced by a British musket ball. You know the rest. In the books you have read

How the British Regulars fired and fled,—

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farmyard wall,

Chasing the redcoats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load. So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm,—

A cry of defiance, and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo for evermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere”.

In 2005, a news release from the Department of Defense reported “Private First Class Michael A. Arciola, 20, of Elmsford, New York, died February 15, 2005, in Al Ramadi, Iraq, from injuries sustained from enemy small arms fire. Arciola was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 503d Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, Camp Casey, Korea”.

In 2005, a news release from the Department of Defense reported “Private First Class Michael A. Arciola, 20, of Elmsford, New York, died February 15, 2005, in Al Ramadi, Iraq, from injuries sustained from enemy small arms fire. Arciola was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 503d Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, Camp Casey, Korea”.

Sometimes, a military chaplain was the only one present at these services. Both Vandenbergs felt that a member of the Air Force family should be present at these funerals. Gladys began to invite other officer’s wives. Over time, a group of women from the Officer’s Wives Club were formed for the purpose.

Sometimes, a military chaplain was the only one present at these services. Both Vandenbergs felt that a member of the Air Force family should be present at these funerals. Gladys began to invite other officer’s wives. Over time, a group of women from the Officer’s Wives Club were formed for the purpose.

The casual visitor cannot help but being struck with the solemnity of such an occasion. Air Force Ladies’ Chairman Sue Ellen Lansell spoke of one service where the only other guest was “one elderly gentlemen who stood at the curb and would not come to the grave site. He was from the Soldier’s Home in Washington, D. C. One soldier walked up to invite him closer, but he said no, he was not family”.

The casual visitor cannot help but being struck with the solemnity of such an occasion. Air Force Ladies’ Chairman Sue Ellen Lansell spoke of one service where the only other guest was “one elderly gentlemen who stood at the curb and would not come to the grave site. He was from the Soldier’s Home in Washington, D. C. One soldier walked up to invite him closer, but he said no, he was not family”.

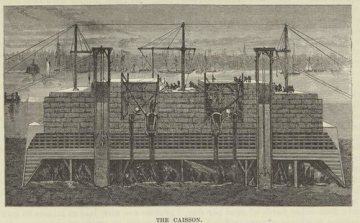

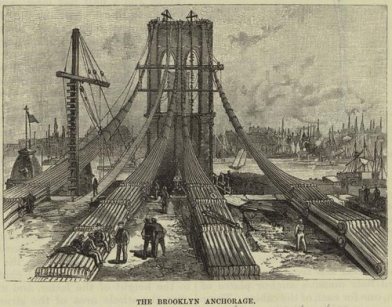

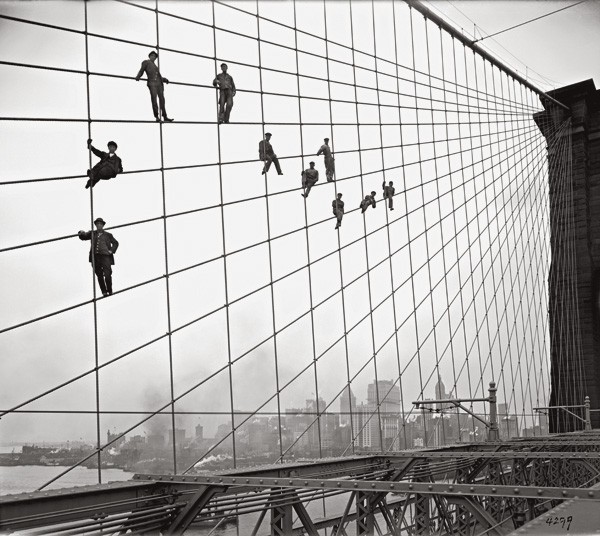

“Lockjaw” is such a sterile term, it doesn’t begin to describe the condition known as Tetanus. In the early stages, the anaerobic bacterium Clostridium Tetani produces tetanospasmin, a neurotoxin producing mild spasms in the jaw muscles. As the disease progresses, sudden and involuntary contractions affect skeletal muscle groups, becoming so powerful that bones are literally fractured as the muscles tear themselves apart. These were the last days of John Roebling, the bridge engineer who would not live to see his most famous work.

“Lockjaw” is such a sterile term, it doesn’t begin to describe the condition known as Tetanus. In the early stages, the anaerobic bacterium Clostridium Tetani produces tetanospasmin, a neurotoxin producing mild spasms in the jaw muscles. As the disease progresses, sudden and involuntary contractions affect skeletal muscle groups, becoming so powerful that bones are literally fractured as the muscles tear themselves apart. These were the last days of John Roebling, the bridge engineer who would not live to see his most famous work.

You must be logged in to post a comment.