Israel was the youngest of eight children borne of the Baline Family in western Siberia and emigrated to the United States, in 1893. In grammar school “Izzy” delivered telegrams and sold newspapers, to help with family finances. Israel’s father Moses died when the boy was only 13 and he took work as a “ Busker”, to support himself.

Everyone who will read this has bought a record I suspect, but the sale of music came long before the age of the phonograph. Buskers or “song pluggers” would perform songs in vaudeville theaters, railroad stations and even street corners in hopes of selling sheet music, of the latest songs.

Even at a young age Israel Baline had a pleasing voice and a natural ear, for music. By 16 he was a singing waiter at the Pelham Cafe in New York’s Chinatown. It was there he taught himself to play the piano and to compose music, with the help of a friend. The boy’s first published work led to a name change when Marie from Sunny Italy came back from the publisher, with a typo. I. Baline was now I. Berlin.

At least that’s the story. Others will tell you Irving Berlin changed his name to sound less ethnic. Be that as it may, the author of American standards like “Puttin’ on the Ritz” and “There’s No Business Like Show Business”, had come of age.

In 1911, Berlin’s “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” sold a million copies and inspired a dance craze still remembered, to this day.

Irving Berlin wrote “God Bless America” during World War 1 but only used it, in 1938. A love song to an adopted country from a kid escaped from the anti-Jewish Russian pogroms of the age the song went on to earn $9.6 million. Every dime of it was donated to the Boy Scouts of America, and Campfire Girls.

Christmas was an unhappy time for Irving Berlin. A devoted husband of 62 years Irving and Ellin (Mackay) lost their only son (also Irving) on Christmas day in 1928, to Sudden Infant death Syndrome. Every year at Christmas was an occasion to visit their baby’s grave.

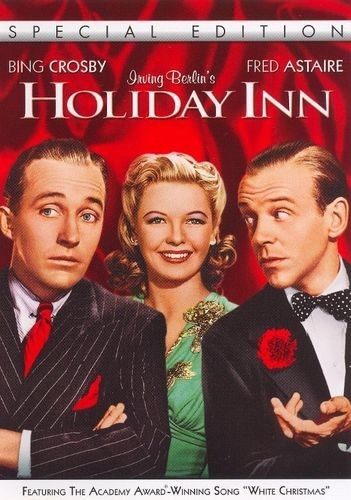

Berlin wrote the best selling record of all time in 1941 but it didn’t start out, the way you might think. In 1940, the composer signed to score a musical for paramount Pictures, about a retired vaudeville performer who opened an inn. The hook was that this particular inn was only open, on holidays. “Holiday Inn” would guide the viewer through a years’ worth of holidays, in music.

As for White Christmas that started out, as a spoof. A satire sung under a palm tree by music industry sophisticates enjoying drinks, around a Beverly hills swimming pool:

The sun is shining, the grass is green

The orange and palm trees sway

There’s never been such a day

In Beverly Hills, L. A.

But it’s December the 24th

And I am longing to be up north….

I’m dreaming of a white Christmas…

(Chorus continues)

Bing Crosby was already famous in 1941. Berlin agreed to include White Christmas in the film, provided that Crosby perform the tune. Crosby himself was on board, from day 1. On hearing the song he told Berlin “You don’t have to worry about this one, Irving.”

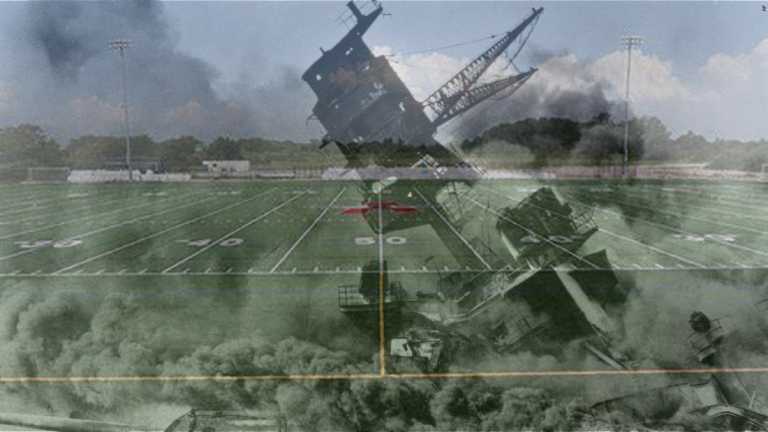

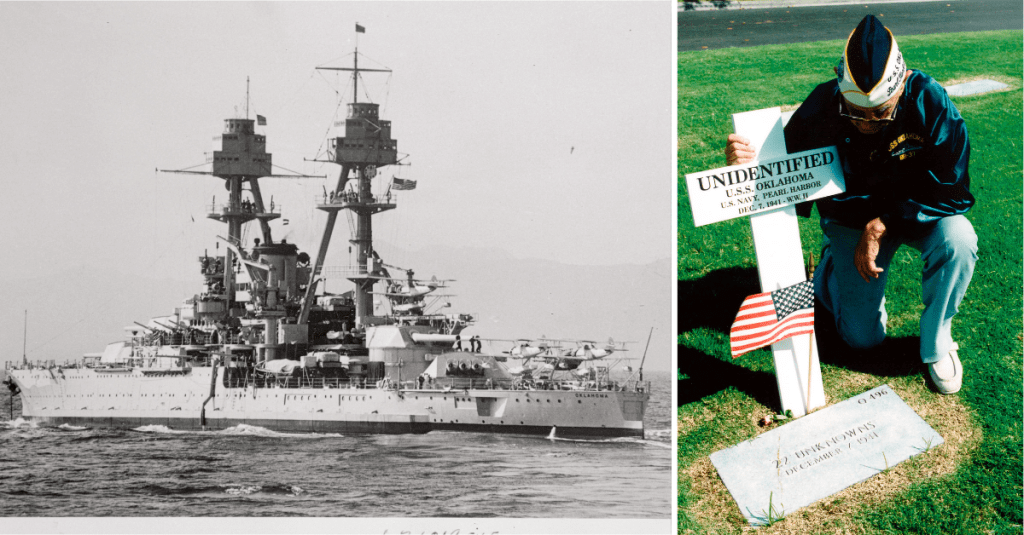

And then the world changed. A mighty sucker punch came out of the east on December 7, 1941, a sneak attack by the air and naval forces of imperial Japan on the American Pacific naval anchorage, at Pearl Harbor.

President Franklin Roosevelt asked for and received a congressional declaration of war on Japan, on December 8. Nazi Germany piled on and declared war on the United States, three days later. The US had entered World War 2.

A generation of men signed up for the draft including Bing Crosby. He would prove too old but this was a loyal American. Crosby would use his gifts at every opportunity and perform for the troops.

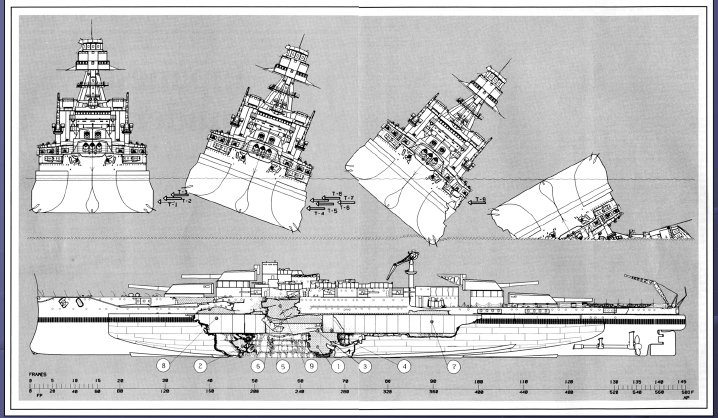

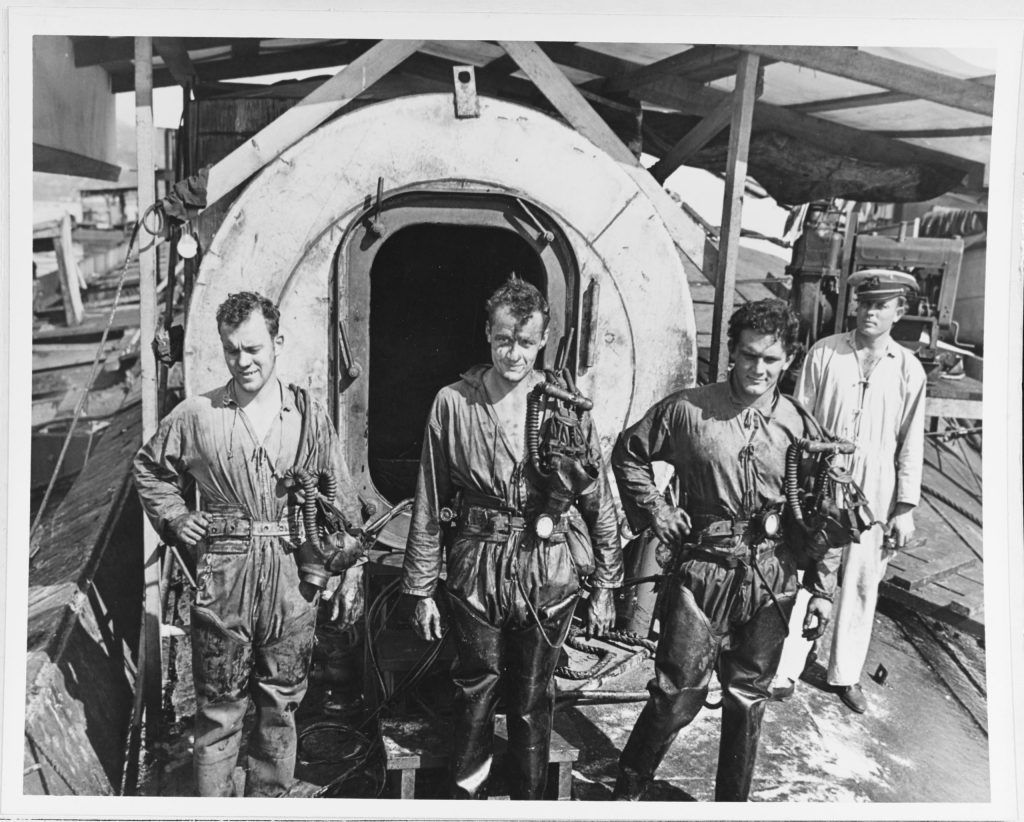

Seventeen days after the attack on Pearl Harbor was Christmas eve, 1941. Bulkhead markings would later reveal that even then, the last survivors on board the USS Oklahoma down there at the bottom of Pearl Harbor were making their last marks on the wall of that black, upside down place in the vain hope of a rescue, that would never come.

Bing Crosby performed the track live that Christmas eve and over the following January, the shortwave broadcast of the Kraft Music Hall reaching troops then fighting for their lives on Corregidor and the Philippines. The set list always started out with a tune, destined to become the official anthem of the US Army: “AS The Caissons Go Rolling Along.”.

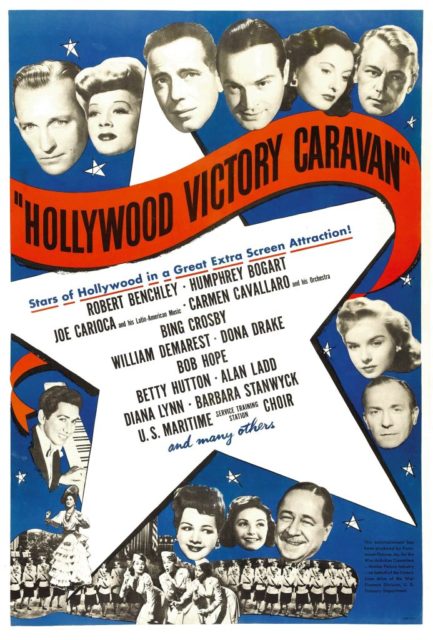

President Roosevelt asked Hollywood to step up, and do its part. Crosby and others formed the Hollywood Victory Caravan in support of the war effort, Carey Grant, Desi Arnaz, Olivia de Havilland and others raising over $700,000 in support of the Army and Navy Relief Society.

When Holiday Inn was released in 1942 Berlin expected Be Careful It’s My Heart to be a hit, a song tied in the film, to Valentine’s day. But a funny thing happened. White Christmas was received by the people who heard it not as satire but a heartfelt reminder of Christmases past and a promise, of Christmas yet to come. Soldiers abroad and their families dreamed alike of a white Christmas, “just like the ones I used to know“.

That first verse quietly went away, never to return.

Fun Fact: Despite Berlin’s songwriting success he didn’t write music and only played the piano in F Sharp. He bought special transposing keyboards so his songs didn’t all sound the same and paid music secretaries to notate and transcribe, his music.

Crosby himself had mixed feelings about performing White Christmas. “I hesitated about doing it” he once told an interviewer, ” because invariably it caused such a nostalgic yearning among the men, that it made them sad. Heaven knows, I didn’t come that far to make them sad. For this reason, several times I tried to cut it out of the show, but these guys just hollered for it.”

White Christmas hit Number 1 on the Hit Parade that November, and never looked back. By Christmas day 1942 the song had barely made it halfway through a ten-week run, at the top spot.

Bing Crosby appeared in over 70 radio shows over the course of the war including 30 Command Performance spots, 13 on Mail Call, 5 appearances on Song Sheet, 19 on GI Journal and at least twice on Jubilee, all in addition to his regular Kraft Music Hall show transcribed on discs and personal appearances before troops on the front lines. A survey among soldiers after the war revealed that Bing Crosby had accomplished more in support of troop morale than Franklin Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower or even, Bob Hope.

It’s a new perspective to look at one of the seminal events of the 20th century, through the eyes of the artist. Imagine for a moment you are Bing Crosby himself, performing for the troops in Belgium and France and Luxembourg in December, 1944. What must it have been like a month later to realize that 75,000 of those men were now casualties in the last great feat of German arms of World War 2, the Battle of the Bulge.

Today, the Guinness Book of World Records names Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” not only the best-selling Christmas single in the United States, but also the best-selling single of all time with estimated sales of over 50 million copies, worldwide.

I hope you enjoyed this story and wish a you Merry Christmas and a safe, healthy and prosperous new year.. May this be the first of many more.

Rick Long, the “Cape Cod Curmudgeon”.

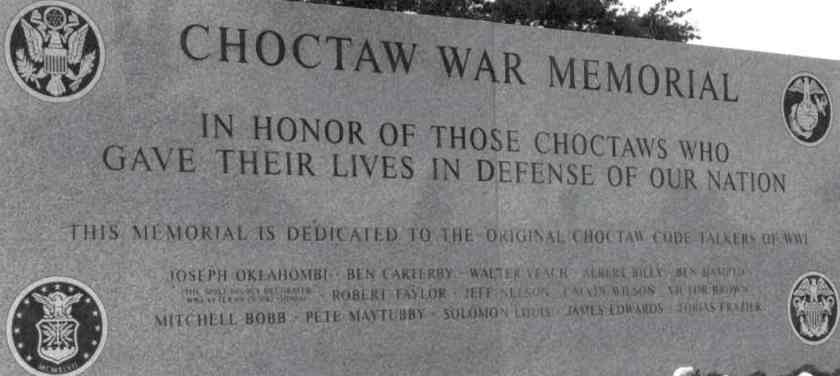

The history of the Navajo code talkers of WWII is well known but by no means, unique. Indigenous Americans of other nations served as code talkers during WW2 including Assiniboine, Lakota and Meskwaki soldiers who did service in the Pacific, North African, and European theaters of the war.

The history of the Navajo code talkers of WWII is well known but by no means, unique. Indigenous Americans of other nations served as code talkers during WW2 including Assiniboine, Lakota and Meskwaki soldiers who did service in the Pacific, North African, and European theaters of the war.

You must be logged in to post a comment.