In thirty-five years as President of Mexico, the administration of José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz Mori had yet to figure out the question of Presidential succession. At first popular following his seizure of power in the coup of 1876, the Porfirian regime soon began to stagnate. Diaz’ policies benefitted ‘el jefe’ cronies and supporters, the wealthy estate-owning “haciendados”, while leaving rural agricultural “campesinos” unable to make a living.

Following the turn of the century, the aging President expressed support for a return to democracy and an intention to step down from office.

An unlikely opponent stepped forward in the person of UC-Berkeley educated lawyer and wealthy hacienda owner, Francisco Madero. Madero wanted a return to democratic elections, but Diaz would have none of it.

Perhaps the octogenarian President expected that his country would beg him to stay, or maybe he changed his mind, but anyone stepping into Diaz’ path, did so at his own risk. Madero fled to the United States, but later returned and faced arrest. Meanwhile, the 80-year old Porfirio Diaz won re-election to an eighth term by a margin that would make Saddam Hussein blush. Voters were outraged by what was clearly a massively corrupt election.

Madero escaped prison and produced the Plan de San Luis Potosí to nullify the elections and overthrow Díaz by force. The table was set for the Mexican Revolution.

Armed conflict ousted Diaz from office the following year, when a free and fair election put Francisco Madero into office. Opposition was quick to form, from both sides of the political spectrum. Conservatives and land owners saw Madero as too weak, his policies too liberal, while former revolutionary fighters and the economically dispossessed, saw him as too conservative. In February 1913, both Madero and his vice president Pino Suárez were run out of office, and murdered by order of military officer, Victoriano Huerta.

Francisco “Pancho” Villa was a Mexican constitutionalist and a Madero supporter. As commander of the División del Norte (Division of the North), Villa fought on behalf of Primer Jefe (“First Chief”) of the Constitutionalist army Venustiano Carranza, but later turned on his erstwhile leader.

American newspaperman and commentator Ambrose Bierce, author of The Devil’s Dictionary and my favorite curmudgeon, joined Pancho Villa’s army in December 1913, as an observer. And then he vanished. Most likely, Bierce faced a firing squad in Chihuahua, but his story remains unknown.

Trouble began between Villistas and the American government when the US declared its support for Villa’s former ally, providing rail transport from Texas to Arizona for 5,000 Carrancista forces.

The Division del Norte was badly defeated by forces loyal to Carranza in July 1915, and again in November. Villa’s army ceased to exist as a military fighting force, reduced to local skirmishes and cross-border raids while foraging the countryside.

A three-way fight broke out on November 26, when Villa’s forces attacked the border town of Nogales, Sonora, and fired across the border at American troops in Nogales, Arizona. On January 11, sixteen American employees of the American Smelting and Refining Company were taken from a train near Santa Isabel Chihuahua, stripped naked, and executed.

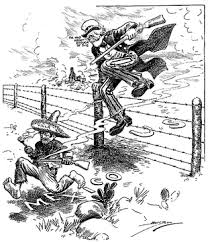

In early March, a force of some 1,500 Villistas were camped along the border three miles south of Columbus New Mexico, when Villa sent spies into Camp Columbus (later renamed Camp Furlong). Informed that Camp Columbus’ fighting strength numbered only thirty or so, a force of some 600 crossed the border around midnight on March 8.

In early March, a force of some 1,500 Villistas were camped along the border three miles south of Columbus New Mexico, when Villa sent spies into Camp Columbus (later renamed Camp Furlong). Informed that Camp Columbus’ fighting strength numbered only thirty or so, a force of some 600 crossed the border around midnight on March 8.

Villa divided his force into two columns, launching a two-pronged assault in the early morning darkness of March 9. Townspeople were asleep at first, awakening to the sounds of burning buildings, and shouts of “Viva Villa! Viva Mexico!”

What began as a pre-dawn raid soon erupted into full-scale battle, as residents poured from homes with hunting rifles and shotguns. The Camp Columbus garrison was taken by surprise but recovered quickly, as barefoot soldiers scrambled into position. Four Hotchkiss M1909 machine guns fired 5,000 rounds apiece before the shooting died down, joined by another 30 troopers with M1903 Springfield rifles.

Pancho Villa proclaimed the raid a success, having captured over 300 rifles and shotguns, 80 horses, and 30 mules. Strategically, the raid was a disaster. The Mexicans had lost 90 to 170 dead they could barely afford, out of a raiding force of 484 men. Official American reports indicate 8, 10 or 11 soldiers killed, plus another 7 or 8 civilians, depending on which report you believe.

The United States government wasted no time in responding. That same day, the President who would win re-election in eight months on the slogan “He kept us out of war” appointed Newton Diehl Baker, Jr. to fill the previously vacant position of Secretary of War. The following day, Woodrow Wilson ordered General John Pershing to capture Pancho Villa, dead or alive.

The United States government wasted no time in responding. That same day, the President who would win re-election in eight months on the slogan “He kept us out of war” appointed Newton Diehl Baker, Jr. to fill the previously vacant position of Secretary of War. The following day, Woodrow Wilson ordered General John Pershing to capture Pancho Villa, dead or alive.

7,000 American troops crossed into Mexico on March 13. It was the first American military expedition to employ mechanized vehicles, including trucks and automobiles to carry supplies and personnel, and Curtiss Jenny aircraft used for reconnaissance.

On March 5, 1913, President William Howard Taft ordered the formation of the 1st Aero squadron, nine aircraft divided into two companies. ‘Aviation’ at that time was not what is, today. Aircraft were highly experimental, many built by the pilots themselves. Crashes were commonplace, and flight lessons all but unheard of. Frequently, general guidelines were given on the ground, and pilots were left to their own devices. One of the early pilots, Captain Benjamin D. Foulois, sent away and received written instruction from Orville Wright, by mail!

The 1st Aero Squadron arrived in New Mexico on March 15, with 8 aircraft, 11 pilots and 82 enlisted men. The first reconnaissance sortie was flown the following day, the first time that American aircraft were used in actual military operations.

The 1st Aero Squadron arrived in New Mexico on March 15, with 8 aircraft, 11 pilots and 82 enlisted men. The first reconnaissance sortie was flown the following day, the first time that American aircraft were used in actual military operations.

Five aircraft departed on the evening of March 19, with orders to report ‘without delay’ to Pershing’s headquarters in Casas Grandes, Mexico. One made it that night, another two straggled in the next morning. One returned to Columbus and 2 others went missing. The problems, it turned out, were insurmountable. 90 HP engines were unable to bring them across 10,000 – 12,000’ mountain peaks, nor could they handle the turbulent winds of mountain passes. Dust storms wrought havoc with engines and, making things worse, the unrelenting heat of the Sonoran Desert de-laminated wooden propellers.

On May 14, a young 2nd Lieutenant in charge of a force of fifteen and three Dodge touring cars got into a running gunfight, while foraging for corn, in Chihuahua. It was the first motorized action in American military history. Three Villistas were killed and strapped to the hoods of the cars and driven back to General Pershing’s headquarters. General Pershing nicknamed that 2nd Lt. “The Bandito”. History remembers his name as George S. Patton.

On May 14, a young 2nd Lieutenant in charge of a force of fifteen and three Dodge touring cars got into a running gunfight, while foraging for corn, in Chihuahua. It was the first motorized action in American military history. Three Villistas were killed and strapped to the hoods of the cars and driven back to General Pershing’s headquarters. General Pershing nicknamed that 2nd Lt. “The Bandito”. History remembers his name as George S. Patton.

During three months of active operations inside Mexico, American forces killed or captured 292 Villistas, but Pancho Villa evaded capture. Pershing publicly proclaimed the operation a success, but privately complained that Wilson imposed too many restrictions, making it impossible to fulfill the mission. “Having dashed into Mexico with the intention of eating the Mexicans raw”, Pershing complained, “we turned back at the first repulse and are now sneaking home under cover, like a whipped cur with its tail between its legs.”

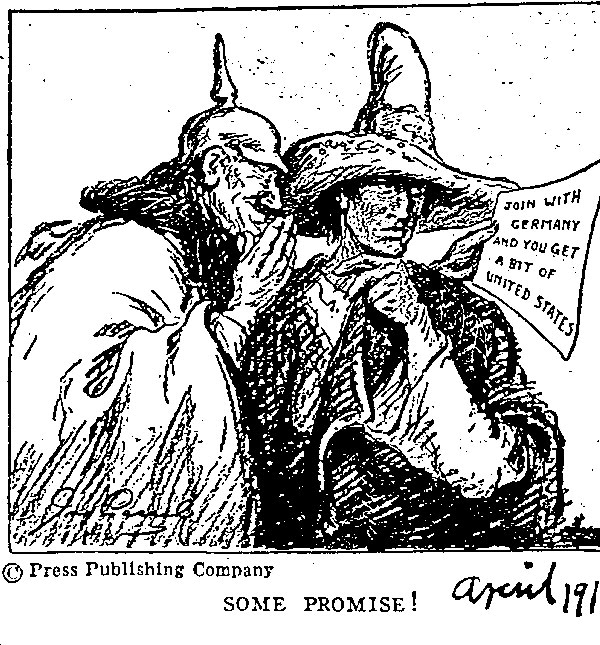

American forces were withdrawn by January 1917, as the European war loomed over American politics. German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann observed political opposition to American operations inside of Mexico, and concluded that a military alliance was possible between the two countries.

The ‘Zimmermann note‘ proposing such an alliance between Germany and Mexico and promising the “restoration of its former territories of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona“, may be seen as the ‘last straw’ that brought the United States into WW1.

In 1620, the 60-ton Pinnace Speedwell departed Delfshaven, meeting with Mayflower at Southampton, Hampshire. The two vessels set out on August 15, but soon had to turn back as Speedwell was taking on water. Speedwell was abandoned after a second failed attempt, Mayflower setting out alone on September 16, 1620, with an estimated 142 passengers and crew.

In 1620, the 60-ton Pinnace Speedwell departed Delfshaven, meeting with Mayflower at Southampton, Hampshire. The two vessels set out on August 15, but soon had to turn back as Speedwell was taking on water. Speedwell was abandoned after a second failed attempt, Mayflower setting out alone on September 16, 1620, with an estimated 142 passengers and crew. As anyone familiar with the area will understand, a month in that place and time convinced them of its unsuitability. By mid-December the Mayflower had crossed Cape Cod Bay and fetched up at Plimoth Harbor.

As anyone familiar with the area will understand, a month in that place and time convinced them of its unsuitability. By mid-December the Mayflower had crossed Cape Cod Bay and fetched up at Plimoth Harbor.

Years later, colonists would go to war against the Wampanoag people and ‘King Philip’, the English name for Metacomet, the son of Massasoit. The Nauset would act as warriors and scouts against the Wampanoag people in King Philip’s War, a conflict which killed some 5,000 New England inhabitants, three quarters of whom were indigenous people.

Years later, colonists would go to war against the Wampanoag people and ‘King Philip’, the English name for Metacomet, the son of Massasoit. The Nauset would act as warriors and scouts against the Wampanoag people in King Philip’s War, a conflict which killed some 5,000 New England inhabitants, three quarters of whom were indigenous people.

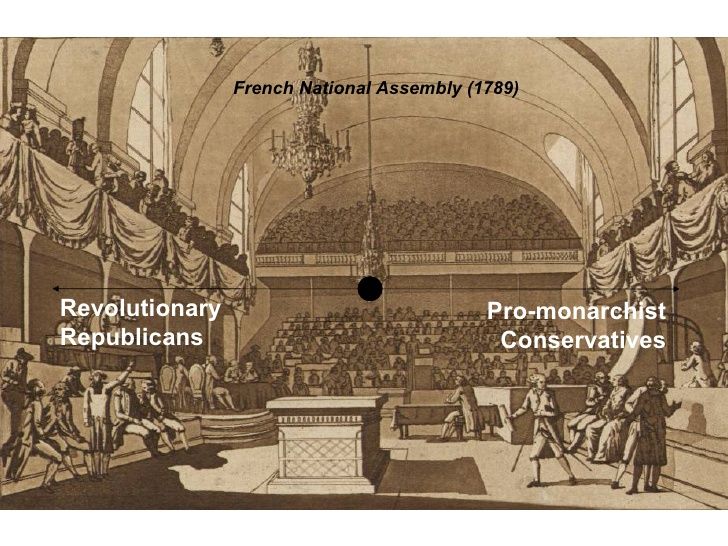

By that time it wasn’t just the “Party of Order” on the right and the “Party of Movement” on the left. Now, the terms began to describe nuances in political philosophy, as well.

By that time it wasn’t just the “Party of Order” on the right and the “Party of Movement” on the left. Now, the terms began to describe nuances in political philosophy, as well.

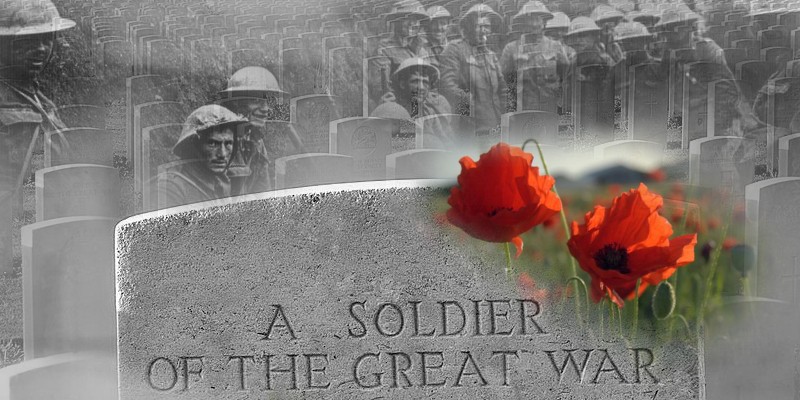

The July Crisis of 1914 was a series of diplomatic maneuverings, culminating in the ultimatum from Austria-Hungary to the Kingdom of Serbia. Vienna, with tacit support from Berlin, made plans to punish Serbia for her role in the assassination, while Russia mobilized armies in support of her Slavic ally.

The July Crisis of 1914 was a series of diplomatic maneuverings, culminating in the ultimatum from Austria-Hungary to the Kingdom of Serbia. Vienna, with tacit support from Berlin, made plans to punish Serbia for her role in the assassination, while Russia mobilized armies in support of her Slavic ally.

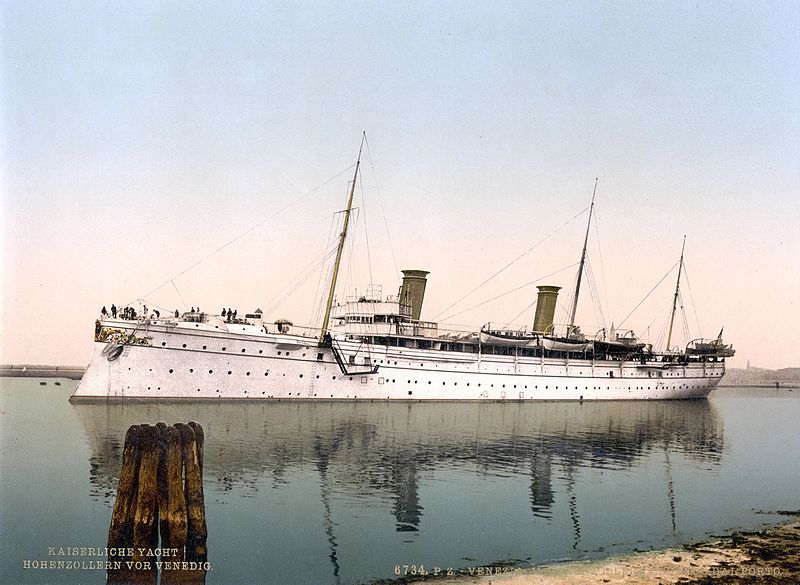

In the days that followed, the Czar would begin the mobilization of men and machines which would place Imperial Russia on a war footing. Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany invaded Belgium, in pursuit of the one-two punch strategy by which it sought first to defeat France, before turning to face the “Russian Steamroller”. England declared war in support of a 75-year-old commitment to protect Belgian neutrality, a treaty obligation German diplomats had dismissed as a “

In the days that followed, the Czar would begin the mobilization of men and machines which would place Imperial Russia on a war footing. Kaiser Wilhelm’s Germany invaded Belgium, in pursuit of the one-two punch strategy by which it sought first to defeat France, before turning to face the “Russian Steamroller”. England declared war in support of a 75-year-old commitment to protect Belgian neutrality, a treaty obligation German diplomats had dismissed as a “

Édouard Séguin, the Paris-born physician and educator best known for his work with the developmentally disabled and a major inspiration to Italian educator Maria Montessori, called the elder Bell’s work “…a greater invention than the telephone by his son, Alexander Graham Bell”.

Édouard Séguin, the Paris-born physician and educator best known for his work with the developmentally disabled and a major inspiration to Italian educator Maria Montessori, called the elder Bell’s work “…a greater invention than the telephone by his son, Alexander Graham Bell”. It was Alexander Graham Bell who first broke through to Helen Keller, a year before Anne Sullivan. The two developed a life-long relationship closely resembling that of father and daughter. Bell made it possible for Keller to attend Radcliffe and graduate in 1904, the first deaf/blind person, ever to do so.

It was Alexander Graham Bell who first broke through to Helen Keller, a year before Anne Sullivan. The two developed a life-long relationship closely resembling that of father and daughter. Bell made it possible for Keller to attend Radcliffe and graduate in 1904, the first deaf/blind person, ever to do so.

In September 1881, Alexander Graham Bell hurriedly invented the first metal detector, as President James Garfield lay dying from an assassin’s bullet. The device was unsuccessful in saving the President, but credited with saving many lives during the Boer War and WW1.

In September 1881, Alexander Graham Bell hurriedly invented the first metal detector, as President James Garfield lay dying from an assassin’s bullet. The device was unsuccessful in saving the President, but credited with saving many lives during the Boer War and WW1.

London’s teaching hospitals at first explored quiet means of taking down what they regarded as an insult to the profession. By November, medical students were crossing the Thames with sledge hammers and crow bars, intending to take matters into their own hands.

London’s teaching hospitals at first explored quiet means of taking down what they regarded as an insult to the profession. By November, medical students were crossing the Thames with sledge hammers and crow bars, intending to take matters into their own hands. Seventy-five years would come and go, before a new Brown Dog memorial was commissioned by the National Anti-Vivisection Society and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

Seventy-five years would come and go, before a new Brown Dog memorial was commissioned by the National Anti-Vivisection Society and the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

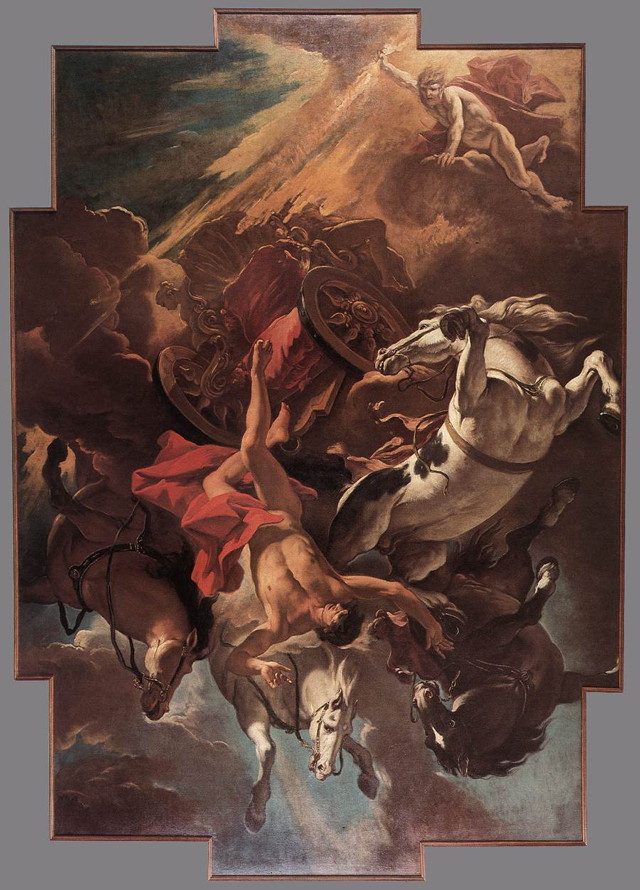

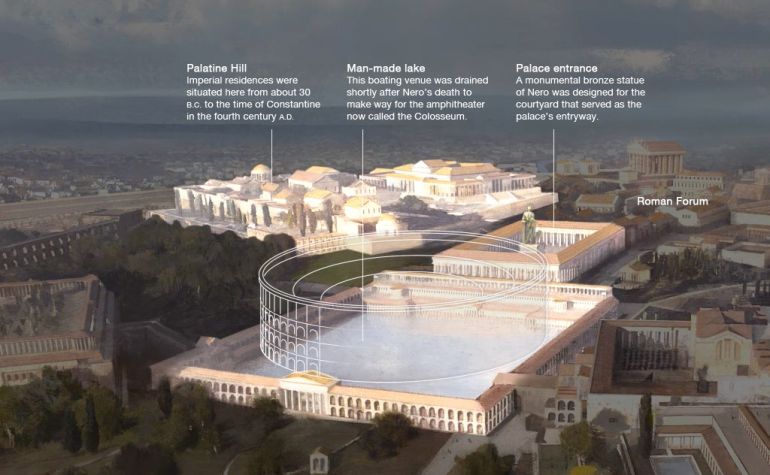

Be that as it may, three things are certain. First, The fire burned for six days, utterly destroying three of the 14 districts of Rome, and severely damaging seven others. Next, Nero used the excuse of the fire to go after the Christians, having many of them arrested and executed. Last, the Domus Aurea (“Golden Palace”) and surrounding “Pleasure Gardens” which the emperor built on the ruins, would be the death of Emperor Nero.

Be that as it may, three things are certain. First, The fire burned for six days, utterly destroying three of the 14 districts of Rome, and severely damaging seven others. Next, Nero used the excuse of the fire to go after the Christians, having many of them arrested and executed. Last, the Domus Aurea (“Golden Palace”) and surrounding “Pleasure Gardens” which the emperor built on the ruins, would be the death of Emperor Nero.

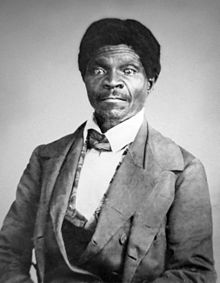

Dr. Emerson died in 1842, leaving his estate to his wife Eliza, who continued to lease the Scotts out as hired slaves.

Dr. Emerson died in 1842, leaving his estate to his wife Eliza, who continued to lease the Scotts out as hired slaves.

You must be logged in to post a comment.