By Spring of 1915, WWI had already devolved into the slugfest of trench warfare that would bleed nation states white and destroy empires. Imperial Germany had held off of unrestricted submarine warfare, believing the tactic would bring the United States into the war against them. Yet this war could not be won on the battlefield alone. They had to make it a war on commerce, to choke of their adversary’s lifeline. Besides, the German view was that ostensibly peaceful shipping was being used to ferry war supplies to the allies, which were going on to kill Germans on the battlefield.

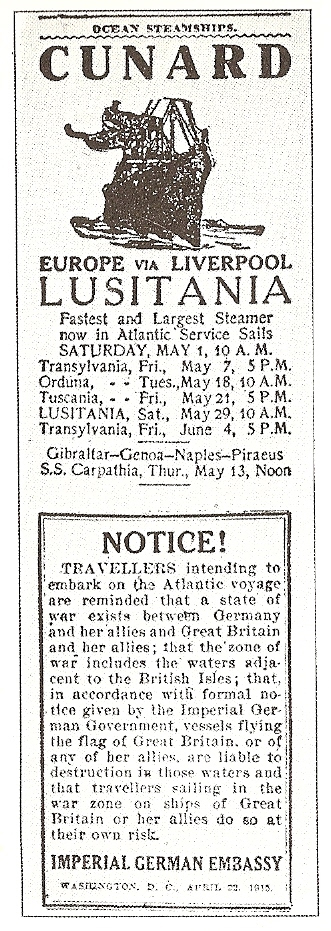

Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare on February 18, 1915. The German embassy took out ads in American newspapers, warning that ships sailing into the war zone, did so at their own risk. That didn’t seem to bother anyone as they boarded RMS Lusitania.

Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare on February 18, 1915. The German embassy took out ads in American newspapers, warning that ships sailing into the war zone, did so at their own risk. That didn’t seem to bother anyone as they boarded RMS Lusitania.

Lusitania was the largest and fastest ship afloat when she was christened in 1904. They called her the “Greyhound of the Seas”, in 1915 she could still outrun almost anything big enough to pose a threat. Lusitania left New York for her 202nd trans-Atlantic crossing on May 1, 1915, carrying 1,959 passengers and crew, 159 of whom were Americans.

All ships heading for Great Britain at this time were instructed to travel at full speed in zigzag patterns, and to be on the lookout for U-boats, but fog forced Captain William Turner to slow down as Lusitania rounded the south coast of Ireland on May 7.

The German U-boat U-20 commanded by Captain Walther Schwieger had targeted Lusitania by early afternoon. At 1:40pm the U-boat fired a single torpedo. The weapon struck Lusitania on her starboard side. Some believe a second explosion was caused by the ignition of ammunition hidden in the cargo hold, others say that coal dust had ignited. Whatever the cause, there is near universal agreement that a second explosion rocked the ship. The damage from this second explosion was catastrophic.

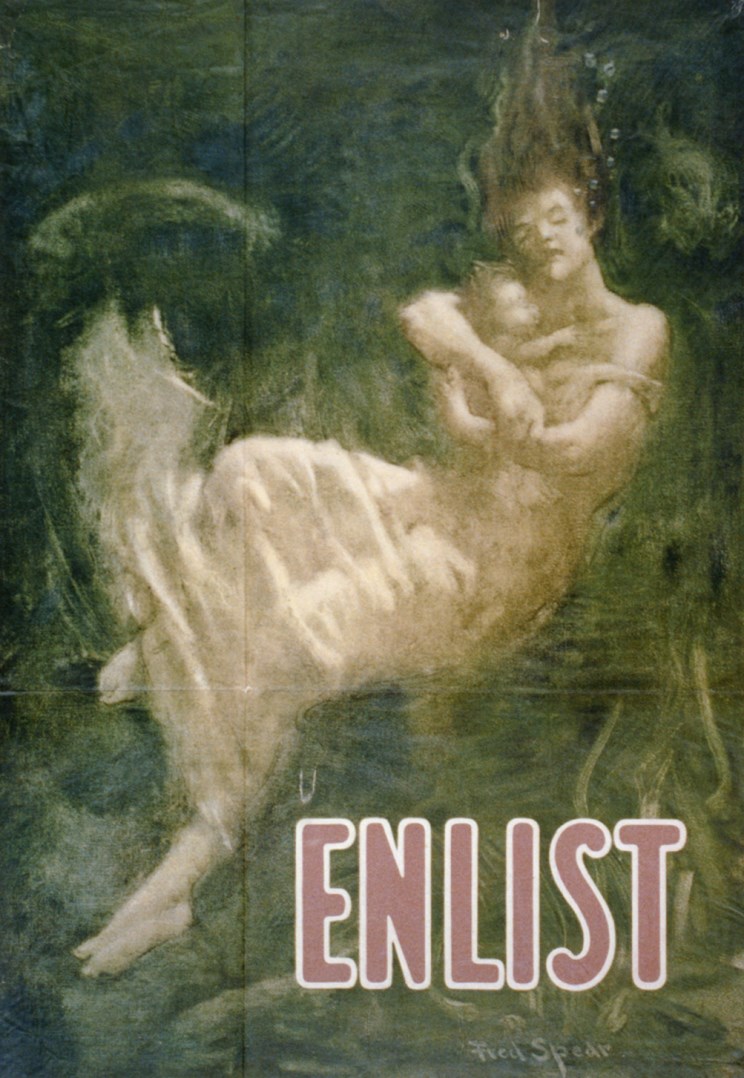

Lusitania quickly began to list, and sank in 18 minutes. There had been enough lifeboats for all the passengers, but the severe list prevented most of them from being launched. Of the 1,959 people on board, 1,198 died, including 128 Americans. 100 of the Americans, were children.

American public opinion was outraged at the loss of life in a war in which the United States was neutral. Imperial Germany, for her part, maintained that Lusitania was illegally transporting munitions intended to kill German boys on European battlefields. Furthermore, the embassy pointed out that ads had been taken out in the New York Times and other newspapers, specifically warning that the liner was subject to attack.

In what’s been called his “too proud to fight” speech three days later, President Woodrow Wilson said “The example of America must be the example not merely of peace because it will not fight, but of peace because peace is the healing and elevating influence of the world and strife is not. There is such a thing as a man being so right it does not need to convince others by force that it is right”.

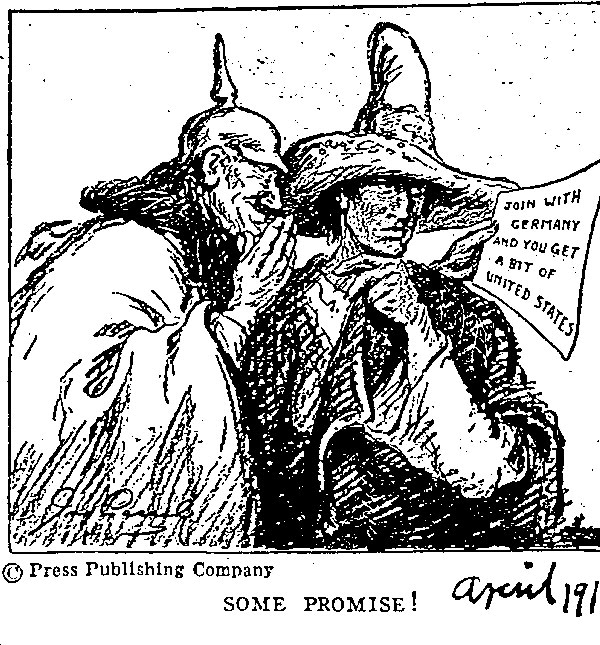

Unrestricted submarine warfare was suspended for a time, and American entry into WWI was averted. The final provocation to war came in January 1917, when the “Zimmermann Telegram” came to light. A communication from the German Foreign Minister to his ambassador in Mexico, the Zimmerman telegram proposed a military alliance between Germany and Mexico in the event of war with the United States, in exchange for “an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona”.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed the same month. In February a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California off the Irish coast, killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew. President Wilson asked for a declaration of war in a speech to a joint session of Congress on April 2. From the text of the speech, it seems the Germans were right. It was the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare which provoked the United States to enter the war against Germany, which it did when Congress declared war on April 6.

Unrestricted submarine warfare was resumed the same month. In February a German U-boat fired two torpedoes at the SS California off the Irish coast, killing 43 of her 205 passengers and crew. President Wilson asked for a declaration of war in a speech to a joint session of Congress on April 2. From the text of the speech, it seems the Germans were right. It was the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare which provoked the United States to enter the war against Germany, which it did when Congress declared war on April 6.

The German view that Lusitania carried contraband ammunition was vindicated as well, but at the time that was far into their future. Decades later, formerly secret British papers revealed the presence of contraband ammunition in the holds of the passenger liner. Divers explored the wreck in 2008, located under 300′ of water off the Head of Kinsale. On board, they found four million US made Remington .303 bullets, stored in unrefrigerated compartments in crates marked “butter”, “lobster” and “eggs”.

A personal postscript to this story: On several occasions, my folks hired an elderly Irish woman to babysit my brothers and me when we were kids, back in the ’60s. As a little girl, Mrs. Crozier was living in Kinsale, back in 1915. Like the rest of her village, she ran out to the cliffs that morning to watch the great liner sink. It was only nine miles off the coast and could be seen, clearly. She must have thought I was a strange kid, but I couldn’t get enough of that story.

Kapaun served as military chaplain toward the end of WWII, before leaving the army in 1946, and rejoining in 1948.

Kapaun served as military chaplain toward the end of WWII, before leaving the army in 1946, and rejoining in 1948.

Starving, suffering from a blood clot in his leg and a severe eye infection, Father Kapaun led Easter services in April, 1951. He was incapacitated a short time later. Chinese guards carried him off to a “hospital” – a fetid, stinking part of the camp known to prisoners as the “Death House”, from which few ever returned. “If I don’t come back”, he said, “tell my Bishop that I died a happy death.”

Starving, suffering from a blood clot in his leg and a severe eye infection, Father Kapaun led Easter services in April, 1951. He was incapacitated a short time later. Chinese guards carried him off to a “hospital” – a fetid, stinking part of the camp known to prisoners as the “Death House”, from which few ever returned. “If I don’t come back”, he said, “tell my Bishop that I died a happy death.” Pope John Paul II named Father Kapaun a “Servant of God” in 1993, the first step toward Roman Catholic Sainthood. On November 9, 2015, the Catholic Diocese of Wichita submitted a 1,066 page report on the life of Chaplain Kapaun, to the Roman Curia at the Vatican. A team of six historians reviewed the case for beatification. On June 21, 2016, the committee unanimously approved the petition. At the time I write this, Father Emil Joseph Kapaun’s supporters continue working to have him declared a Saint of the Roman Catholic Church, for his lifesaving ministrations at Pyoktong.

Pope John Paul II named Father Kapaun a “Servant of God” in 1993, the first step toward Roman Catholic Sainthood. On November 9, 2015, the Catholic Diocese of Wichita submitted a 1,066 page report on the life of Chaplain Kapaun, to the Roman Curia at the Vatican. A team of six historians reviewed the case for beatification. On June 21, 2016, the committee unanimously approved the petition. At the time I write this, Father Emil Joseph Kapaun’s supporters continue working to have him declared a Saint of the Roman Catholic Church, for his lifesaving ministrations at Pyoktong.

With sandbags, explosives, and the device which made the thing work, the total payload was about a thousand pounds on liftoff. The first such device was released on November 3, 1944, beginning the crossing to the west coast of North America. 9,300 such balloons were released with military payloads, between late 1944 and April, 1945.

With sandbags, explosives, and the device which made the thing work, the total payload was about a thousand pounds on liftoff. The first such device was released on November 3, 1944, beginning the crossing to the west coast of North America. 9,300 such balloons were released with military payloads, between late 1944 and April, 1945. In 1945, intercontinental weapons were more in the realm of science fiction. As these devices began to appear, American authorities theorized that they originated with submarine-based beach assaults, German POW camps, and even the internment camps into which the Roosevelt administration herded Japanese Americans.

In 1945, intercontinental weapons were more in the realm of science fiction. As these devices began to appear, American authorities theorized that they originated with submarine-based beach assaults, German POW camps, and even the internment camps into which the Roosevelt administration herded Japanese Americans.

American authorities were alarmed. Anti-personnel and incendiary bombs were relatively low grade threats. Not so the biological weapons Japanese military authorities were known to be developing at the infamous Unit 731, in northern China.

American authorities were alarmed. Anti-personnel and incendiary bombs were relatively low grade threats. Not so the biological weapons Japanese military authorities were known to be developing at the infamous Unit 731, in northern China.

France would leave the country following defeat by Viet Minh forces at

France would leave the country following defeat by Viet Minh forces at  Richard M. Nixon won overwhelming victory in the Presidential election of 1968, running on a platform including a “secret plan” to end the war in Vietnam.

Richard M. Nixon won overwhelming victory in the Presidential election of 1968, running on a platform including a “secret plan” to end the war in Vietnam. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and other “New Left” organizations staged sit-ins in the fall of 1968. Demonstrations became violent six months later, resulting in 58 arrests. Four SDS leaders spent six months in prison.

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and other “New Left” organizations staged sit-ins in the fall of 1968. Demonstrations became violent six months later, resulting in 58 arrests. Four SDS leaders spent six months in prison.

Tear gas failed to break up the crowd and several canisters were thrown back, with near-constant volleys of rocks, bottles and other projectiles. 77 National Guardsmen advanced in line-abreast, as screaming protesters closed behind them. Guardsmen briefly assumed firing positions when cornered near a chain link fence, though no one fired.

Tear gas failed to break up the crowd and several canisters were thrown back, with near-constant volleys of rocks, bottles and other projectiles. 77 National Guardsmen advanced in line-abreast, as screaming protesters closed behind them. Guardsmen briefly assumed firing positions when cornered near a chain link fence, though no one fired.

Gold Selleck Silliman, himself a widower, merged his household with that of Mary on May 24, 1775, in a marriage described as “rooted in lasting friendship, deep affection, and mutual respect”. The two would have two children together, who survived into adulthood: Gold Selleck (called Sellek) born in October 1777, and Benjamin, born in August 1779.

Gold Selleck Silliman, himself a widower, merged his household with that of Mary on May 24, 1775, in a marriage described as “rooted in lasting friendship, deep affection, and mutual respect”. The two would have two children together, who survived into adulthood: Gold Selleck (called Sellek) born in October 1777, and Benjamin, born in August 1779.

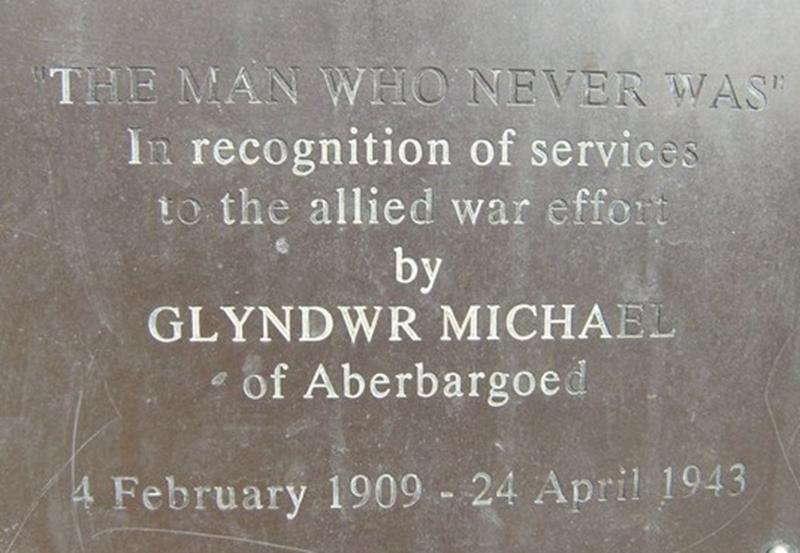

Be that as it may, this cause of death is difficult to detect, The condition of the corpse was close to that of someone who had died at sea, of hypothermia and drowning. The dead man’s parents were both deceased, there were no known relatives and the man died friendless. So it was that Glyndwr Michael became the “Man who Never Was”.

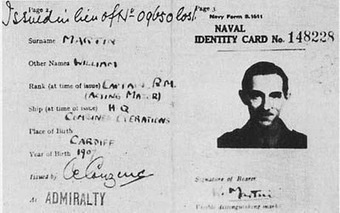

Be that as it may, this cause of death is difficult to detect, The condition of the corpse was close to that of someone who had died at sea, of hypothermia and drowning. The dead man’s parents were both deceased, there were no known relatives and the man died friendless. So it was that Glyndwr Michael became the “Man who Never Was”. A “fiancée” was furnished for Major Martin, in the form of MI5 clerk “Pam”. “Major Martin” carried her snapshot, along with two love letters, and a jeweler’s bill for a diamond engagement ring.

A “fiancée” was furnished for Major Martin, in the form of MI5 clerk “Pam”. “Major Martin” carried her snapshot, along with two love letters, and a jeweler’s bill for a diamond engagement ring.

Field Marshall Helmuth von Moltke once said “No battle plan ever survives contact with the enemy”. So it was in the tiny Belgian city where German plans met with ruin, on the road to Dunkirk. Native Dutch speakers called the place Leper. Today we know it as Ypres (Ee-pres), since battle maps of the time were drawn up in French. To the Tommys of the British Expeditionary Force, the place was “Wipers”.

Field Marshall Helmuth von Moltke once said “No battle plan ever survives contact with the enemy”. So it was in the tiny Belgian city where German plans met with ruin, on the road to Dunkirk. Native Dutch speakers called the place Leper. Today we know it as Ypres (Ee-pres), since battle maps of the time were drawn up in French. To the Tommys of the British Expeditionary Force, the place was “Wipers”. The second Battle for Ypres began with a new and terrifying weapon on April 22, 1915. German troops placed 5,730 gas cylinders weighing 90 pounds apiece, along a four-mile front. Allied troops must have looked on in wonder, as that vast yellow-green carpet crept toward their lines.

The second Battle for Ypres began with a new and terrifying weapon on April 22, 1915. German troops placed 5,730 gas cylinders weighing 90 pounds apiece, along a four-mile front. Allied troops must have looked on in wonder, as that vast yellow-green carpet crept toward their lines.

Units of all sizes, from individual companies to army corps, lightened the load of the “War to end all Wars”, with some kind of unit journal.

Units of all sizes, from individual companies to army corps, lightened the load of the “War to end all Wars”, with some kind of unit journal.

Mark Kurlansky, author of “Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World”, laments the 1990s collapse of the Cod fishery, saying the species finds itself “at the wrong end of a 1,000-year fishing spree.”

Mark Kurlansky, author of “Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World”, laments the 1990s collapse of the Cod fishery, saying the species finds itself “at the wrong end of a 1,000-year fishing spree.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.